Introduction

The makeup, anatomy, and histology of the pediatric skeletal system is not just a smaller version of the adult form; rather, it is unique in that it allows for rapid growth and change throughout development from childhood to adulthood.[1] The majority of differences between adult and pediatric skeletal systems are due to the open physis in the pediatric population, which allows for continued growth prior to skeletal maturation during puberty and adulthood.[1] The physis is the growth plate in long bones, including phalanges, fibula, tibia, femur, radius, ulna, and humerus. It allows for bone growth from a cartilage base, known as endochondral ossification, which differs from bone growth from mesenchymal tissue or intramembranous ossification.[2] The physis is located towards the end of the long bone, with the epiphysis above it and the metaphysis below it.[1] Long bones like the femur have 2 physes separated by a diaphysis, which is the shaft of a long bone. However, long bones like the phalanges have only one physis.

The physis is split into 4 zones: (1) the reserve or resting zone, which is made up of hyaline cartilage; (2) the zone of proliferation, which is made up of multiplying chondrocytes that arrange into lacunae (lakes); (3) the zone of hypertrophy, where the chondrocytes stop dividing and start enlarging; and (4) the zone of calcification, where minerals are deposited into the lacunae to calcify the cartilage. The calcified cartilage breaks down, allowing for vascular invasion and osteoblastic/osteoclastic bone matrix deposition and remodeling.

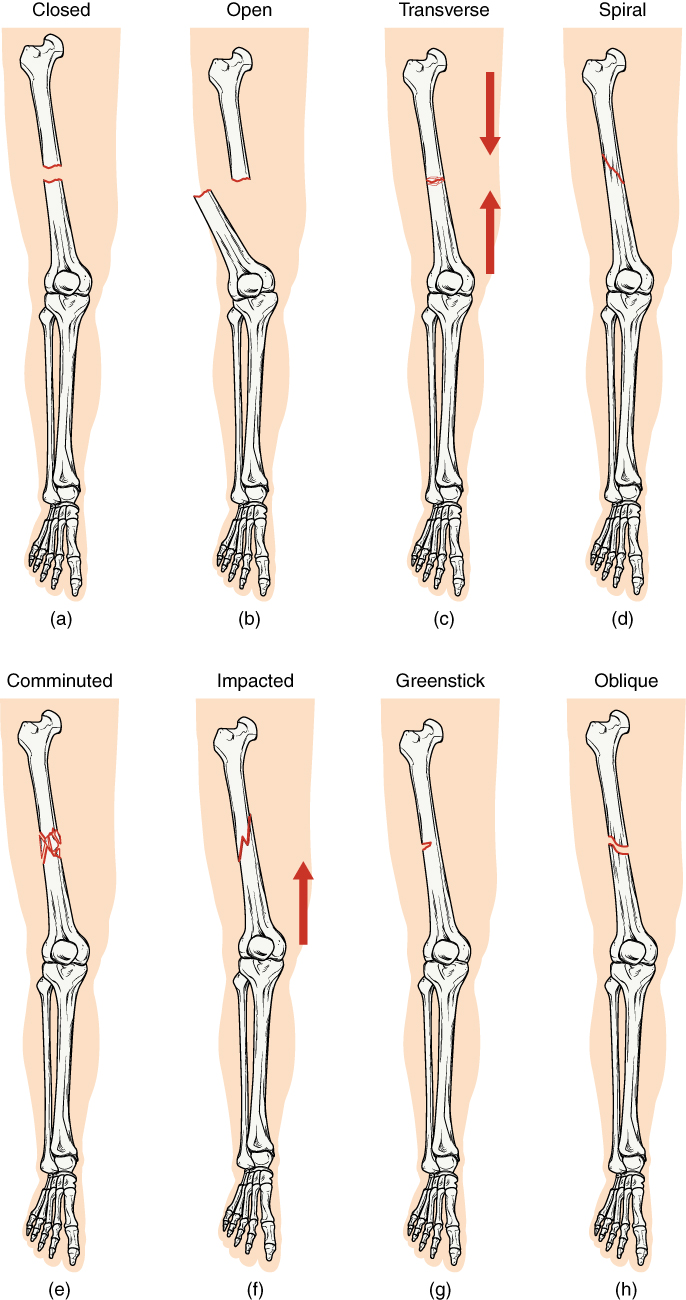

Therefore, prior to ossification, the majority of pediatric bone is just calcified cartilage, which is very compliant when compared to the ossified bones of adults.[1] Due to their increased compliance, pediatric bones tend to have more bowing and bending injuries under stress that would cause a fracture in an adult bone.[1] Furthermore, the pediatric periosteum is more active, thicker, and stronger in children, which greatly decreases the chance of open fractures and fracture displacement. These and other qualities of the pediatric periosteum, as well as the increased compliance of the pediatric bone, are responsible for the unique fracture patterns seen in pediatric patients. These fracture patterns include greenstick, torus, and spiral injuries, which are bending injuries rather than full-thickness cortical breaks.[1]

A greenstick fracture is a partial thickness fracture where only the cortex and periosteum are interrupted on one side of the bone while they remain uninterrupted on the other side.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Greenstick fractures occur most commonly after a fall on an outstretched arm (FOOSH); however, they can also occur due to other types of trauma, including motor vehicle collisions, sports injuries, or non-accidental trauma where the child is hit with an object. Malnutrition, specifically vitamin-D deficiency, increases the risk of greenstick fractures of the long bones after a trauma.

Epidemiology

Approximately 12% of all pediatric emergency department visits in the United States are due to musculoskeletal injuries. Fractures make up a large percentage of musculoskeletal injuries resulting in significant morbidity and complications. Greenstick fractures are most likely to be found in the pediatric population under 10 years of age but can occur in any age group, including adults.[3] There is an equal incidence rate in female and male patients; however, male patients are more likely to sustain fractures.[4][5][6]

Pathophysiology

A greenstick fracture is a partial thickness fracture where only the cortex and periosteum are interrupted on one side of the bone but remain uninterrupted on the other.[1] They occur most often in long bones, including the fibula, tibia, ulna, radius, humerus, and clavicle. Most commonly, they occur in the forearm and arm, involving either the ulna, radius, or humerus.[1][3] This is because people brace falls with an outstretched arm, resulting in fractures to the upper extremities.

Greenstick fractures can also occur in the face, chest, scapula, and virtually every bone in the body, but with much less frequency than long bones.[3] For example, greenstick fractures can occur in the jaw and nose.[7] Condylar fractures are the most common pediatric mandibular fractures, accounting for up to 55% of all mandibular fractures.[8] There are 3 types of condylar fractures. Low subcondylar fractures are the most common and are incomplete greenstick fractures the majority of the time.[8] Nasal trauma most commonly leads to greenstick fractures in the pediatric population due to an unfused midline suture and the majority of cartilage composition of the nasal bones.[9]

Histopathology

The periosteum, metaphysis, and diaphysis are strong and continuous from the metaphysis to the epiphysis, surrounding the physis to provide support. Although the walls surrounding the physis are strong, the hypertrophic zone of the physis is a weak point where fractures commonly occur. Injury to the physis or the epiphyseal plate can lead to bone growth retardation, as the vascular bed that supports physical growth originates from the epiphyseal plate.

Although the diaphysis and metaphysis are calcified in adults, they are weaker than in the pediatric population, leading to greenstick, torus, and plastic bending injuries. Greenstick fractures can occur anywhere throughout the diaphysis and metaphysis but are no longer called greenstick fractures if they involve the physis, as those are classified as Salter-Harris fractures. Greenstick fractures are theorized to occur due to the increased ratio of collagen matrix with more immature cross-links and a higher immature/mature crosslink ratio.[2]

History and Physical

History and physical exams of patients with greenstick fractures are no different from patients with other types of fractures. Age, gender, anatomic location, soft tissue involvement (assessment of open versus closed), and mechanism of injury are all important features of the history. Location, soft tissue involvement, and neurovascular status are important aspects of a physical exam. Furthermore, the joints below and above the site should be evaluated for occult fractures or multiple fractures.

Findings on the history commonly include accidental trauma like FOOSH but can include history like being hit with a baseball bat or other item and other forms of accidental trauma.[10] However, non-accidental trauma should always be considered.[10] Depending on the age of the patient, the patient will either refuse to move the injured extremity, cry inconsolably, complain of pain in the injured extremity, or be protective of the injured extremity.

Common physical findings include decreased range of motion, pain to palpation, and ecchymosis over the injured area.[10] More critical findings include edema, tenting if displaced, soft tissue changes such as abrasion or laceration, and signs of injury to the neurovascular bundle.[10] When assessing a distal forearm, there should be suspicion for median nerve injury, which can occur with greenstick fractures. A full neurological check should be done with all traumatic injuries. Other findings that may indicate non-accidental trauma include multiple injuries and ecchymoses in different stages of healing that do not follow an age-appropriate injury pattern.

Evaluation

Diagnostic evaluation includes an x-ray of the injured extremity or area of complaint. Typical X-ray findings demonstrate a bending injury with a fracture line that does not completely go through the bone.[1][10]There is a fracture of the periosteum and cortex on one side (the tension side) which does not extend to the other side of the cortex and periosteum.[10] On an x-ray, there is a visible fracture on the tension side, with the opposite side of the bone demonstrating plastic deformation due to compressive forces.[1][10]

Treatment / Management

If the degree of angulation is significant, then the healthcare provider needs to perform a closed reduction and immobilization.[10] All greenstick fractures require immobilization, and casting several days after the initial injury decreases the risk of the need to recast due to increasing edema post fracture. Orthopedic referral at the initial visit is generally recommended but depends on the degree of angulation and age of the child.

Cast immobilization of long bone greenstick fractures should last approximately six weeks.[10][11] The type of cast depends on the location of the fracture. Distal fractures can be put in short arm casts, while proximal fractures require long arm casting and may be switched to a short arm cast midway through the healing process at approximately three weeks. Patients with proximal fractures require closer orthopedic follow-up.[10][12] However, all greenstick fractures should have some type of orthopedic follow-up due to their unstable nature and increased likelihood of refracture and displacement compared to buckle or plastic bending injuries.[10]

Although less commonly practiced, greenstick fractures may be treated with splinting if there is only a small amount of angulation and if there is close follow-up with the family or patient.[13] Splinting may be less costly and will allow for the removal of the splint for showers.

Differential Diagnosis

Salter-Harris fracture, torus fracture, toddler fracture (non-displaced spiral fracture of the distal tibia), spiral fracture, non-accidental fracture, open fracture, pathologic fracture, non-displaced fracture, and plastic deformities, among others.[1]

Prognosis

Generally, the prognosis is good; the majority of greenstick fractures heal well without functional or gross changes in the appearance of the injured bone. However, if not properly immobilized and without proper orthopedic follow-up, there is the risk of refracture, complete fracture, and displacement of the fracture.[10]

Complications

Greenstick fractures have a high risk of refracture due to their instability and the need to be quickly immobilized.[10][12] A primary greenstick fracture can result in a high rate of recurrent forearm fractures.[10] According to one case series, after reduction of the radius greenstick fracture, further radiographic analysis of the proximal and distal segments of the radius should be done to ensure that the rotational position of each matches the other.[14] This is referred to as the radius crossover sign and may help reduce the risk of deformity and loss of forearm motion.[14] One case report demonstrated a greenstick scapula fracture that resulted in physical exam findings of scapular winging.[15]

Consultations

Orthopedic consultation should be considered in the initial exam and diagnosis but is not necessary for simple greenstick fractures without angulation.[10] However, an orthopedic referral is necessary after the initial visit for close follow-up, casting, and to reduce the risk of complications.[10]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Trauma and sports injuries, most commonly due to a FOOSH, may lead to fractures and require immediate evaluation to prevent complications. Greenstick fractures require immediate immobilization to prevent recurrent fractures, complete fractures, or displacement. Activities with a high risk of falling should be avoided while the patient is healing, as there is a high risk of refracture and complete fracture.

Pearls and Other Issues

Fractures of the neonatal skull most commonly are greenstick fractures.[16] Although usually seen in the pediatric population, greenstick fractures can also occur in adults.[17]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Greenstick fractures are usually seen in the pediatric population and are best managed by an interprofessional team that includes the pediatrician, emergency department physician, orthopedic nurse, and orthopedic surgeon. If the degree of angulation is significant, then the healthcare provider needs to perform a closed reduction and immobilization.[10] All greenstick fractures require immobilization, and casting several days after the initial injury decreases the risk of the need to recast due to increasing edema post fracture. Orthopedic referral at the initial visit is generally recommended but depends on the degree of angulation and age of the child.

The outcomes for most children are good. However, follow-up is required to ensure proper healing is occurring.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Chasm RM, Swencki SA. Pediatric orthopedic emergencies. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2010 Nov:28(4):907-26. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2010.06.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20971397]

Berteau JP, Gineyts E, Pithioux M, Baron C, Boivin G, Lasaygues P, Chabrand P, Follet H. Ratio between mature and immature enzymatic cross-links correlates with post-yield cortical bone behavior: An insight into greenstick fractures of the child fibula. Bone. 2015 Oct:79():190-5. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.05.045. Epub 2015 Jun 14 [PubMed PMID: 26079997]

Cheng JC, Shen WY. Limb fracture pattern in different pediatric age groups: a study of 3,350 children. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 1993:7(1):15-22 [PubMed PMID: 8433194]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNaranje SM,Erali RA,Warner WC Jr,Sawyer JR,Kelly DM, Epidemiology of Pediatric Fractures Presenting to Emergency Departments in the United States. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2016 Jun [PubMed PMID: 26177059]

Mathison DJ, Agrawal D. An update on the epidemiology of pediatric fractures. Pediatric emergency care. 2010 Aug:26(8):594-603; quiz 604-6. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181eb838d. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20693861]

Nellans KW, Kowalski E, Chung KC. The epidemiology of distal radius fractures. Hand clinics. 2012 May:28(2):113-25. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2012.02.001. Epub 2012 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 22554654]

Coban YK, Bekircan K. Greenstick Fracture of the Mandible in a Child. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2017 Jun:28(4):1116-1117. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003642. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28277480]

Sharma S, Vashistha A, Chugh A, Kumar D, Bihani U, Trehan M, Nigam AG. Pediatric mandibular fractures: a review. International journal of clinical pediatric dentistry. 2009 May:2(2):1-5. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1022. Epub 2009 Aug 26 [PubMed PMID: 25206104]

Chandra SR, Zemplenyi KS. Issues in Pediatric Craniofacial Trauma. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2017 Nov:25(4):581-591. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2017.06.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28941510]

Noonan KJ, Price CT. Forearm and distal radius fractures in children. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 1998 May-Jun:6(3):146-56 [PubMed PMID: 9689186]

Schmuck T,Altermatt S,Büchler P,Klima-Lange D,Krieg A,Lutz N,Muermann J,Slongo T,Sossai R,Hasler C, Greenstick fractures of the middle third of the forearm. A prospective multi-centre study. European journal of pediatric surgery : official journal of Austrian Association of Pediatric Surgery ... [et al] = Zeitschrift fur Kinderchirurgie. 2010 Sep [PubMed PMID: 20577951]

Franklin CC, Robinson J, Noonan K, Flynn JM. Evidence-based medicine: management of pediatric forearm fractures. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2012 Sep:32 Suppl 2():S131-4. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e318259543b. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22890452]

Acree JS, Schlechter J, Buzin S. Cost analysis and performance in distal pediatric forearm fractures: is a short-arm cast superior to a sugar-tong splint? Journal of pediatric orthopedics. Part B. 2017 Sep:26(5):424-428. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0000000000000382. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27602915]

Wright PB, Crepeau AE, Herrera-Soto JA, Price CT. Radius crossover sign: an indication of malreduced radius shaft greenstick fractures. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2012 Jun:32(4):e15-9. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3182468cec. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22584847]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBowen TR,Miller F, Greenstick fracture of the scapula: a cause of scapular winging. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 2006 Feb [PubMed PMID: 16462570]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCho SM, Kim HG, Yoon SH, Chang KH, Park MS, Park YH, Choi MS. Reappraisal of Neonatal Greenstick Skull Fractures Caused by Birth Injuries: Comparison of 3-Dimensional Reconstructed Computed Tomography and Simple Skull Radiographs. World neurosurgery. 2018 Jan:109():e305-e312. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.09.168. Epub 2017 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 28989045]

Casey PJ, Moed BR. Greenstick fractures of the radius in adults: a report of two cases. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 1996:10(3):209-12 [PubMed PMID: 8667114]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence