Introduction

The foot is a complex anatomic structure composed of numerous bones, joints, ligaments, muscles, and tendons responsible for the complex coordinated movements of gait and our ability to stand upright. By definition, the foot is the lower extremity distal to the ankle joint. The ankle joint (sometimes referred to as the tibiotalar joint) is the result of the assembly of the talus and the recess formed by the distal tibia and fibula. The foot has of 26 bones (tarsal, metatarsal and phalanges) which subdivide into groups termed hindfoot, midfoot and forefoot. The articular surfaces of bones have a covering of articular cartilage. The articulation or joints are invested by joint capsules and ligaments, which lend stability to the joints. Also, there are 29 muscles responsible for the movement of the osseous structures of the foot and ankle. The muscles are attached to the osseous structures via tendons. Innervation and vascularity are likewise complex. The major arterial structures include the anterior tibial, posterior tibial and peroneal or fibular arteries. Each of these main arteries has numerous branches which this article will discuss further below. The major nerves innervating the foot and ankle include the tibial, deep peroneal, and sural nerves, each of which has numerous branches. Finally, there is subcutaneous fat, fascia, and skin completing the anatomic components of the foot and ankle. Not surprisingly, acute injury, chronic repetitive injury, and degenerative or inflammatory arthropathy are common causes for presentation to emergency departments or primary care providers. If not treated properly, these ailments can result in chronic disability.[1][2][3][4][5]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The ankle or tibiotalar joint constitutes the junction of the lower leg and foot. The osseous components of the ankle joint include the distal tibia, distal fibula, and talus. The distal tibia and fibula together form a recess for the talus. The articular surface of the distal tibia forms by the medial malleolus and the tibial plafond, the horizontal portion of the distal tibial articular surface. The distal portion of the fibula is referred to as the lateral malleolus. The talar dome is the proximal articular surface of the talus which sits within the recess created by the distal tibia and fibula. As mentioned previously, ligamentous structures and joint capsules lend stability to joints. The medial ligaments are jointly referred to as the deltoid ligament complex, which is comprised of a deep layer (anterior and posterior tibiotalar ligaments) which are intra-articular and superficial layers (tibionavicular, tibiospring, tibiocalcaneal and superficial posterior tibiotalar). On the ankle's lateral side are syndesmotic ligaments (anterior inferior tibiofibular, posterior inferior tibiofibular and interosseous) which are the ligaments involved in "high" ankle sprains and the lower lateral ligaments (anterior talofibular, posterior talofibular, and calcaneofibular). The lower ligaments are more commonly injured, specifically the anterior talofibular and calcaneofibular.[1][3][6][7][8]

The anatomic structures below the ankle joint comprise the foot, which includes 26 bones; the tarsal (7), metatarsal (5) and phalanges (14). The foot subdivides into hindfoot, midfoot, and forefoot.

The hindfoot, the most posterior aspect of the foot, is composed of the talus and calcaneus, two of the seven tarsal bones. The talus and calcaneus articulation is referred to as the subtalar joint, which has three facets on each of the talus and calcaneus. The posterior subtalar joint constitutes the largest component of the subtalar joint. The subtalar joint allows for ankle and hindfoot inversion and eversion.[3]

The midfoot is made up of five of the seven tarsal bones: navicular, cuboid, and medial, middle, and lateral cuneiforms. The junction between the hind and midfoot is termed the Chopart joint, which includes the talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints. The navicular also articulates with the medial, middle, and lateral cuneiform bones distally. The cuboid forms the base of the lateral column of the feet and articulates with the base of the fourth and fifth metatarsal bones distally. The calcaneonavicular or spring ligaments together with the posterior tibialis tendon, contribute to the stability of the midfoot and arch.[3][9][10]

The forefoot is the most anterior aspect of the foot and includes the metatarsals, phalanges (toes), and sesamoid bones. There are a metatarsal and three phalanges for each digit apart from the great toe, which only has two phalanges. The articulation of the midfoot and forefoot forms the Lisfranc joint. The three cuneiforms articulate with the 1st, 2nd and 3rd metatarsal bases while the cuboid articulates with the base of the 4th and 5th metatarsal bones. The middle cuneiform is the smallest which allows for interlocking (keystone) of the second metatarsal bone at the Lisfranc joint contributing to the stability. The Lisfranc ligament has three components (dorsal, interosseous and plantar) connecting the base of the second metatarsal bone to the medial cuneiform. Injury to the Lisfranc ligaments can lead to midfoot instability and if left untreated chronic deformity progressing to a neuropathic joint. In addition to the Lisfranc ligaments, there are intertarsal and intermetatarsal ligaments contributing to the stability of the mid and forefoot.

The forefoot further divides into medial and lateral columns. Each column is composed of rays, a metatarsal, and its associated phalanges. Rays one through three make up the middle column while rays four and five make up the lateral column. The first and second rays are the primary weight-bearing components of the forefoot. The first and second metatarsophalangeal joints (MTP joints) are key components of the forefoot playing critical roles in balance, weight-bearing, and gait. The complex capsular and ligamentous anatomy of the MTP joints is commonly referred to as the plantar plates. Injury to the 1st MTP joint capsuloligamentous structures is referred to as "turf toe."[11]

Muscles and tendons are predominately responsible for the coordinated movements of the osseous structures of the foot and ankle but also serve a secondary function to lend stability to the osseous and ligamentous anatomy. The muscles and tendons will receive more detailed discussion in a later section.

This complex anatomy of the foot and ankle together with the remainder of the lower limb functions to efficiently support the body weight and provide for locomotion. The foot specifically acts as a platform for stance, a shock absorber for impact during gait, and a lever to propel the body forward during stepping.

Gait is made up of repetitive cycles of the stance phase when the foot is on the ground (foot strike, mid stance, and terminal stance) and the swing phase when the foot is in the air. When running, there is an additional phase: the float phase when both feet are off the ground.[12]

During walking foot strike, the foot is supinated, and Chopart joint is locked, making the foot rigid when the heel first lands. The foot pronates and flattens during mid-stance coming in full contact with the surface. Terminal stance is then characterized by propulsion via heel off and toe-off. The Lisfranc joint allows slight dorsiflexion and plantarflexion. Force then transfers to the middle column of the forefoot during the toe-off phase of stepping, and the forefoot supinates. The lateral column acts during the final phase of push-off while stepping, providing primarily sensory input. The base of the fifth metatarsal alone absorbs significant force and weight. The combination of fixed midfoot, slightly flexible Lisfranc joint, and flexible metatarsophalangeal joints create a lever for propulsion during gait.[12]

Embryology

The appendicular system develops during weeks 4 to 8 of gestation beginning with a swelling on the ventrolateral surface that becomes a limb bud under the influence of fibroblast growth factors with development progressing in a proximal to distal direction. The rudimentary foot appears at 4.5 weeks gestation with the cartilaginous skeleton and muscles quickly becoming visible, followed by the formation of the toes. The skeletal structures are of mesoderm origin arising from mesenchymal condensations, the first stage of skeletogenesis occurs.[2]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

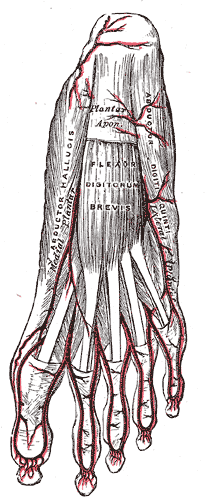

The anterior tibial and posterior tibial arteries supply the foot with blood. The anterior tibial artery splits into the dorsalis pedis artery (dorsal and medial) and the lateral tarsal artery (lateral) to supply the dorsum of the foot. These combine distally forming a ring with the transversely running arcuate artery. Branches of the arcuate artery supply the dorsal rays. On the foot's plantar aspect, the posterior tibial artery splits into the medial plantar artery and lateral plantar artery. These two arteries combine distally forming a ring with the transversely running deep plantar arch. Branches off the deep plantar arch supply the plantar rays. The courses of the anterior and posterior tibial arteries mirror each other in the transverse plane. The fibular (peroneal) artery runs along the posterior lateral ankle and hindfoot. There is a communicating branch that connects the fibular and posterior tibial arteries. The fibular artery gives of deep perforating branches at the level of the ankle and distal syndesmosis as well as the lateral malleolar branch. Calcaneal branches are the terminal vessels of the fibular artery.[13][14]

Nerves

The nerves of the foot and ankle include the saphenous, superficial fibular, deep fibular, medial plantar, lateral plantar, sural, and calcaneal branches.

The saphenous nerve originates from the femoral nerve and supplies the skin of the medial ankle and foot to the distal aspect of the first metatarsal.

The superficial and deep fibular nerves originate from the common fibular nerve. The superficial fibular nerve supplies the skin of the dorsal foot and digits apart from the dorsolateral first digit, dorsomedial second digit, and lateral fifth digit. The deep fibular nerve supplies the extensor digitorum brevis muscle and the skin of the dorsolateral first digit and dorsomedial second digit.[15][16]

The medial and lateral plantar nerves originate from the tibial nerve. The division occurs at the level of the ankle within the tarsal tunnel. The medial plantar nerve travels deep to the abductor hallucis muscle. It will branch into the common plantar and proper plantar digital nerves of the first through fourth digits. The medial plantar nerve and it's terminal branches innervate the flexor digitorum brevis, first lumbrical, abductor hallicus, and flexor hallicus brevis muscles. Additionally, it provides sensory innervation to the skin of the plantar surface of the first three digits, medial fourth digit, and medial foot. The lateral plantar nerve obliquely along the lateral aspect of the plantar foot between the flexor digitorum brevis and quadratus plantae. It innervates the flexor digiti minimi brevis, abductor digiti minimi, quadratus plantae, adductor hallicus, lateral three lumbricals, and plantar/dorsal interossei muscles. The lateral plantar is also responsible for sensory innervation to the skin of the lateral plantar surface of the fifth and lateral fourth digit and lateral foot.[15][16][15]

The sural nerve originates from branches of both the common fibular nerve and the tibial nerve. It supplies the lateral hind and midfoot. The calcaneal branches originate from the tibial and sural nerves and sensory innervation to the skin of the heel.[15][16]

Sciatic

- Tibial

- Medial sural cutaneous

- Medial calcaneal

- Medial plantar

- Common plantar digital nerves

- Proper plantar digital nerves

- Lateral plantar

- Deep branch

- Superficial branch

- Common plantar digital nerves

- Proper plantar digital nerves

- Common fibular (peroneal)

- Deep fibular

- Lateral terminal branch

- Medial terminal branch

- Superficial

- Medial dorsal cutaneous

- Intermediate dorsal cutaneous

- Deep fibular

- Sural

- Lateral dorsal cutaneous

- Lateral calcaneal

Muscles

The muscles acting on the foot can classify as extrinsic and intrinsic muscles (29 total; 10 extrinsic and 19 intrinsic).[2] The extrinsic muscles originate outside of the foot, but provide support for the foot, while the intrinsic muscles originate within and lie entirely within the foot providing fine motor movement.

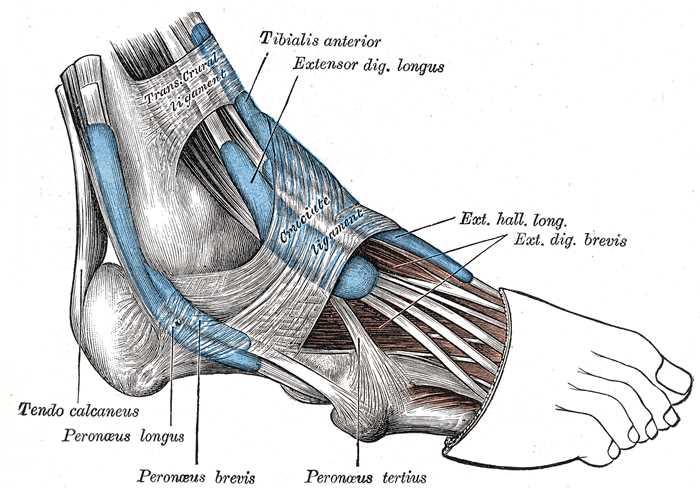

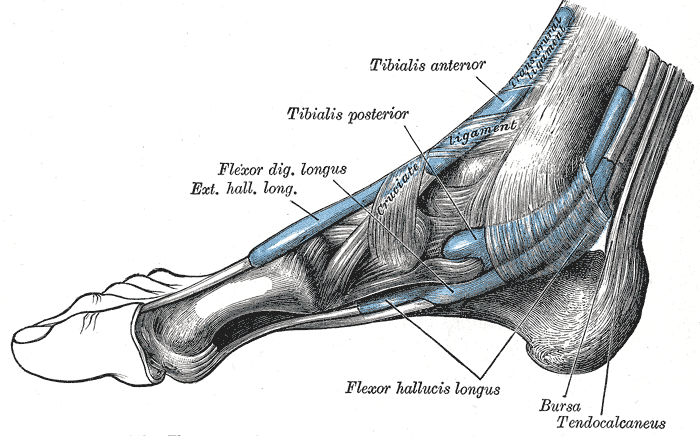

The extrinsic muscles can be organized by compartment. Anterior leg foot dorsiflexors include tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus, and extensor hallucis longus. Within the posterior lateral compartment of the ankle are the peroneus longus and peroneus brevis muscles which are involved in plantar flexion of the foot. In the posterior medial compartment of the ankle, deep to the flexor retinaculum lie the tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus, and flexor hallucis longus muscles which are also involved in plantar flexion. Finally, within the posterior ankle and hindfoot superficial to the flexor retinaculum lies the soleus muscle with the conjoined tendon of the gastrocnemius muscles forming the Achilles tendon. Adjacent to the Achilles tendon is the plantar tendon, both attached to the posterior calcaneus and are involved in foot plantar flexion.[2]

The intrinsic muscles can be organized by which digits they power: the first digit, the central three digits, and the fifth digit.

The muscles of the great toe include the abductor hallucis, the flexor hallucis brevis, and the adductor hallucis. The abductor hallucis originates on the calcaneal tuberosity and inserts on the proximal phalanx of the first digit. It abducts the great toe to help maintain the foot arch. The flexor hallucis brevis which is involved in flexion of the first digit originates at the lateral cuneiform and cuboid and also inserts on the proximal phalanx of the first digit. The adductor hallucis has two heads. One head originates obliquely across the central midfoot at the proximal two through four metatarsals, and the other originates via the metatarsophalangeal ligaments three through five. They insert into the first proximal phalanx. This muscle adducts to the great toe.[2]

The muscles of the central toes include the four lumbricals, quadratus plantae, flexor digitorum brevis, and the dorsal and plantar interossei. The lumbricals originate on the flexor digitorum longus tendon and insert on the extensor digitorum longus tendon. This muscle acts to extend the interphalangeal joints and to flex the metatarsophalangeal joints. The quadratus plantae originates on the plantar calcaneus and inserts into the flexor digitorum longus tendon, thereby flexing the distal phalanges. The flexor digitorum brevis originates at the calcaneal tuberosity and inserts at the middle three phalanges aiding in the flexion of the second through fifth digits. The interosseous muscles which adduct the digits, originate at metatarsals three through five and also insert at the middle three phalanges.[2]

The muscles of the little toe include the abductor digiti minimi, flexor digiti minimi, and the opponens digiti minimi. The abductor digiti minimi originates from the calcaneal tuberosity and inserts on the fifth metatarsal base. The flexor digit minimi originates at the fifth metatarsal base and inserts on the proximal phalanx of the little toe.[2]

Physiologic Variants

There are numerous anatomic variants of the foot, some of which are incidental and of little clinical significance while others are pathologic. Anatomics variants include ossicles, muscles, and variations in alignment. Familiarity with these anatomic variants is important so as not to mistake them with a pathologic process or identify those that may predispose to a pathologic process.

There is some measure of debate in the literature as to the true nature of ossicles. Some evidence suggests that at least some are congenital developmental variants while others believe they are the sequela of prior traumatic injury. The most frequently encountered accessory ossicles of the foot and ankle include the os trigonum, os navicularis, os peroneum, os supranaviculare, and os intermetatarseum. The os trigonum has been implicated in posterior ankle impingement, also referred to as os trigonum syndrome, common in ballet dancers. There are three types of os navicularis, types I and III are asymptomatic while type II has a pseudo articulation with the adjacent navicular bone and can be symptomatic. In severe cases that have failed conservative treatment, the ossicle may undergo excision. Finally, the os peroneum has been shown to be involved with peroneal longus tendon pathology (tendinosis or tears) as well as the painful os peroneum syndrome (POPS). Other ossicles are important because they may be mistaken for pathologies, such as interpreting the os intermetatarsum for the fleck sign in a Lisfranc injury or the os supranaviculare being mistaken for a capsular or chip fracture of the dorsal navicular.[17][18][6][19]

Sesamoids are structurally very similar to accessory ossicles. The most common sesamoids are the medial and lateral hallux sesamoids associated with the first metatarsophalangeal joint. The hallux sesamoids are almost universally present, while sesamoids associated with the lesser metatarsophalangeal joints are less common. The hallux sesamoids can be bipartite or multipartite as normal anatomic variants which clinicians must distinguish from sesamoid fracture or fragmentation associated with avascular necrosis.[17][20]

The most common accessory muscles of the foot and ankle occur in the ankle. These include the peroneus tertius, peroneus quartus, accessory soleus, and flexor digitoreum accessorius longus (FDAL). The peroneus tertius lies within the anterior compartment laterally and is rarely of clinical significance. The peroneus quartus lies within the posterolateral compartment along the posteromedial border of the peroneus longus tendon. It also is generally asymptomatic although it can be mistaken for tears of the peroneus brevis or longus tendons. Additionally, it has been implicated as a cause for tears of the longus and brevis due to crowding and mass effect. Within the posteromedial compartment beneath the flexor retinaculum lies the FDAL which like other accessory muscles is usually asymptomatic but can be a cause of tarsal tunnel syndrome. Tarsal tunnel syndrome is a compressive neuropathy of the tibial nerve resulting in pain and burning along the medial aspect and sole.[21][22]

Osseous variations include coalitions and bipartite bones. The most common coalitions of the foot and ankle include talocalcaneal and calcaneonavicular. Coalitions can be fibrous or osseous. Fibrous coalitions are similar to pseudoarticulations and can be symptomatic. Osseous coalitions may cause malalignment of other osseous structures and result in altered weight-bearing, which also may be symptomatic or result in premature osteoarthritis. Coalitions can be difficult to appreciate on radiographs secondary to the normal overlap of osseous structures. However, the research describes some radiographic signs. The continuous "C" sign refers to the radiographic appearance resulting from talocalcaneal coalition. This sign is present when there is a fusion of the posterior subtalar joint. It should is worth noting that fibrous or incomplete coalitions may not result in this radiographic sign and may only be appreciated on CT or MRI. Calcaneonavicular coalition is the result of an elongated anterior process fusing with the navicular, or forming a pseudo articulation. The radiographic sign described with calcaneonavicular coalition is the anteater sign; this is most visible on the lateral or oblique views of the foot. Bipartite bones result from congenital incomplete fusion of ossification centers. One such example is the bipartite medial cuneiform. These are generally incidental symptomatic findings.[23][24]

Finally, variations in foot alignment can be congenital or acquired. Examples include pes cavus (high arch), pes planus (flat foot), midfoot laxity or collapse (combination of pes planus and plantar angulation of the talus often occurs in association with hindfoot valgus), hindfoot valgus, and hallux valgus to name a few. A complete discussion of foot alignment is beyond the scope of this article. Acquired pes planus and midfoot collapse have been associated with posterior tibialis and spring ligament dysfunction as both of these structures support the arch of the foot. Hallux valgus deformity is a malalignment of the first ray which can cause widening of the forefoot, altered weight-bearing, bunion formation, and osteoarthritis.[10]

Clinical Significance

Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome

Tarsal tunnel syndrome is neuropathy resulting from an entrapment that occurs along the posteromedial ankle secondary to the compression of the tibial nerve (or one of its branches). Patients present with pain and paresthesias of the heel, sole, and toes. On physical exam, patients may have a positive Tinel sign which refers to paresthesias resulting from the percussion of the involved nerve. The tarsal tunnel is the space located along the posterior medial ankle between the flexor retinaculum (roof) and the tibia, talus, and calcaneus (floor). The normal structures within the tarsal tunnel include the posterior tibialis, flexor digitorum longus, and flexor hallicus longus muscles, posterior tibial artery and vein, and the tibial nerve. The majority of cases are idiopathic. However other etiologies include compression secondary to ganglion cysts, varicosities, tenosynovitis, tumors, accessory muscles or fracture deformities. A trial of conservative treatment with anti-inflammatory medications, physical therapy, or image-guided therapeutic injections. In patients who fail conservative treatment surgical intervention can be considered depending on the etiology of the syndrome (i.e., excision of the mass, if present, or cutting the flexor retinaculum to alleviate compression of the tibial nerve).[25]

Os Trigonum Syndrome

Os trigonum syndrome is also referred to as posterior ankle impingement. Classically, the syndrome is described in ballet dancers but can occur in any patient performing repetitive plantarflexion (also common in soccer players). Usually, it is a unilateral process, but there are reports of bilateral cases. Patients present with posterior ankle pain exacerbated by plantar flexion. Predisposing factors include elongated stieda process, os trigonum, prior fracture of the posterior process of the talus, or posterior tibia. Patients normally respond to conservative treatment (rest, ice, anti-inflammatory medications, or injections).[6][18]

Lisfranc Injury

Lisfranc injuries are fracture-dislocation injuries of the tarsal-metatarsal articulations (Lisfranc joint), the junction of the midfoot and forefoot. Classically, the injury refers to the disruption of the Lisfranc ligament, which is comprised of three bands traversing the space between the medial cuneiform and base of the second metatarsal bone. This a common injury that may result from multiple various traumatic etiologies which if undiagnosed, can lead to chronic disability. Mechanisms include crush injury. However, the classic mechanism is indirect loading on a plantarflexed foot. Subtypes of injury include homolateral, divergent, and isolated. Homolateral refers to lateral displacement of the first through fifth metatarsal bones or lateral displacement of the second through fifth metatarsal bones with the normal alignment of the first. Divergent refers to lateral displacement of the 2nd through fifth metatarsal bones with medial displacement of the 1st. Dislocation of 1 or 2 metatarsal bones dorsally in isolation is referred to as the isolated type. On radiographs look for malalignment of the tarsometatarsal joints on the AP and oblique views of the foot. On the lateral view, dorsal foot soft tissue swelling with or without a step-off at the tarsometatarsal joint in a patient with trauma is highly suspicious. The fractures associated with Lisfranc injury are difficult to appreciate on radiographs due to overlap of osseous structures. CT will often show much more extensive injury than appreciated on initial radiographs. On the AP view of the foot, an avulsion fracture of the Lisfranc ligament may present as the "fleck" sign, a small fracture fragment interposed between the base of the 1st and 2nd metatarsal bones.[26]

Stress Injury

Stress injuries of the foot and ankle are common in athletes and military recruits. A stress injury is the result of abnormal (increased) stress on normal bone, a chronic repetitive overuse injury. The pattern and presentation are very similar to insufficiency fractures, which occur in patients with abnormal (weakened) bone exposed to normal stresses. These etiologies include osteoporosis, metabolic bone disease (hyperparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, vitamin deficiency), steroid use, collagen vascular disease, and alcoholism, to name a few. Common locations include the posterior calcaneal tuberosity, cuboid adjacent to the tarsometatarsal joint, anterior talus, navicular, the base of the first through third metatarsal bones, and second through fourth metatarsal necks. These injuries can be difficult to appreciate on radiographs. Radiographic findings include periostitis, linear sclerosis, or less commonly a lucent fracture line. In patients with serious clinical concern for stress injury, further imaging may be necessary with MRI or nuclear medicine bone scan.[27]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Extrinsic Foot Muscles. This medial view of the right foot shows the tendons of the tibialis anterior, tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus, extensor hallucis longus, and flexor hallucis longus. The retrocalcaneal bursa, tendo calcaneus (Achilles tendon), and transcrural and cruciate ligaments are also shown.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Khan IA, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Foot Talus. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31082130]

Card RK, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Foot Muscles. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969527]

Brockett CL, Chapman GJ. Biomechanics of the ankle. Orthopaedics and trauma. 2016 Jun:30(3):232-238 [PubMed PMID: 27594929]

Stirling P, MacKenzie SP, Maempel JF, McCann C, Ray R, Clement ND, White TO, Keating JF. Patient-reported functional outcomes and health-related quality of life following fractures of the talus. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2019 Jul:101(6):399-404. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2019.0044. Epub 2019 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 31155885]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDe Boer AS, Schepers T, Panneman MJ, Van Beeck EF, Van Lieshout EM. Health care consumption and costs due to foot and ankle injuries in the Netherlands, 1986-2010. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2014 Apr 12:15():128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-128. Epub 2014 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 24725554]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRussell TG, Byerly DW. Talus Fracture. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969509]

Shamrock AG, Byerly DW. Talar Neck Fractures. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194455]

Manganaro D, Alsayouri K. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Ankle Joint. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31424742]

Massen FK, Baumbach SF, Herterich V, Böcker W, Waizy H, Polzer H. Fractures to the anterior process of the calcaneus - Clinical results following functional treatment. Injury. 2019 Oct:50(10):1781-1786. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2019.06.008. Epub 2019 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 31178146]

Arain A, Harrington MC, Rosenbaum AJ. Adult-Acquired Flatfoot. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194335]

Nery C, Fonseca LF, Gonçalves JP, Mansur N, Lemos A, Maringolo L, Fonseca LF. First MTP joint instability - Expanding the concept of "Turf-toe" injuries. Foot and ankle surgery : official journal of the European Society of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. 2020 Jan:26(1):47-53. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2018.11.009. Epub 2018 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 30509556]

Han K, Bae K, Levine N, Yang J, Lee JS. Biomechanical Effect of Foot Orthoses on Rearfoot Motions and Joint Moment Parameters in Patients with Flexible Flatfoot. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2019 Aug 8:25():5920-5928. doi: 10.12659/MSM.918782. Epub 2019 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 31393860]

Lezak B, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Foot Veins. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194435]

Lezak B, Wehrle CJ, Summers S. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Posterior Tibial Artery. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725666]

Tang A, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Foot Nerves. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725977]

Desai SS, Cohen-Levy WB. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Tibial Nerve. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725713]

Guo S, Yan YY, Lee SSY, Tan TJ. Accessory ossicles of the foot-an imaging conundrum. Emergency radiology. 2019 Aug:26(4):465-478. doi: 10.1007/s10140-019-01688-x. Epub 2019 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 30963314]

Vosseller JT, Dennis ER, Bronner S. Ankle Injuries in Dancers. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2019 Aug 15:27(16):582-589. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-18-00596. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30789380]

Gomes MDR, Pinto AP, Fabián AA, Gomes TJM, Navarro A, Oliva XM. The Os Peroneum incidence - A cadaveric study. Foot and ankle surgery : official journal of the European Society of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. 2020 Apr:26(3):325-327. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2019.04.009. Epub 2019 Apr 27 [PubMed PMID: 31084989]

Stein CJ, Sugimoto D, Slick NR, Lanois CJ, Dahlberg BW, Zwicker RL, Micheli LJ. Hallux sesamoid fractures in young athletes. The Physician and sportsmedicine. 2019 Nov:47(4):441-447. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2019.1622246. Epub 2019 Jun 5 [PubMed PMID: 31109214]

Aparisi Gómez MP, Aparisi F, Bartoloni A, Ferrando Fons MA, Battista G, Guglielmi G, Bazzocchi A. Anatomical variation in the ankle and foot: from incidental finding to inductor of pathology. Part I: ankle and hindfoot. Insights into imaging. 2019 Jul 31:10(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0746-2. Epub 2019 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 31363861]

Aparisi Gómez MP, Aparisi F, Bartoloni A, Ferrando Fons MA, Battista G, Guglielmi G, Bazzocchi A. Anatomical variation in the ankle and foot: from incidental finding to inductor of pathology. Part II: midfooot and forefoot. Insights into imaging. 2019 Jul 31:10(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0747-1. Epub 2019 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 31363862]

Farid A, Faber FWM. Bilateral Triple Talocalcaneal, Calcaneonavicular, and Talonavicular Tarsal Coalition: A Case Report. The Journal of foot and ankle surgery : official publication of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. 2019 Mar:58(2):374-376. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2018.08.047. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30850104]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSwensen SJ, Otsuka NY. Tarsal Coalitions--Calcaneonavicular Coalitions. Foot and ankle clinics. 2015 Dec:20(4):669-79. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2015.08.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26589085]

Neary KC, Chang E, Kreulen C, Giza E. Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome Secondary to Accessory Musculature: A Case Report. Foot & ankle specialist. 2019 Dec:12(6):549-554. doi: 10.1177/1938640019863277. Epub 2019 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 31409132]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMoracia-Ochagavía I, Rodríguez-Merchán EC. Lisfranc fracture-dislocations: current management. EFORT open reviews. 2019 Jul:4(7):430-444. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.4.180076. Epub 2019 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 31423327]

Ruddick GK, Lovell GA, Drew MK, Fallon KE. Epidemiology of bone stress injuries in Australian high performance athletes: A retrospective cohort study. Journal of science and medicine in sport. 2019 Oct:22(10):1114-1118. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2019.06.008. Epub 2019 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 31307905]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence