Introduction

Endometriosis is a common, estrogen-dependent, inflammatory, gynecologic disease process in which normal endometrial tissue is abnormally present outside the uterine cavity. Endometriomas are cystic lesions that stem from endometriosis. Endometriomas are most commonly found in the ovaries. Endometriosis affects approximately 10% of reproductive-aged women and is a common cause of chronic pain, dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, and infertility. Most commonly, endometriosis is found within the pelvis, specifically on the ovaries.[1]

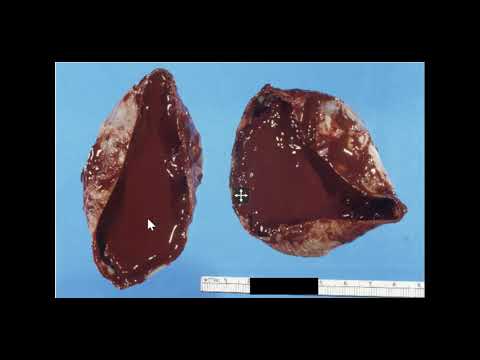

Endometriomas are the most common manifestation of endometriosis on the ovary. However, implants can also be found throughout the abdomen, such as on the bowel, within prior surgical incisions, and even in rare cases in distant locations of the body, such as the cerebellum.[2] Approximately 17 to 44% of women diagnosed with endometriosis will experience an endometrioma. These lesions are commonly referred to as chocolate cysts due to the thick dark brown appearance of the fluid contained within them.[3] Endometriomas indicate a more severe disease state in patients with endometriosis and can lead to specific issues, such as decreased ovarian reserve.[4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Endometriomas are most commonly thought to be caused when the seeding of ectopic endometrial tissue occurs, most often on the ovary, bleeds, causing a hematoma. This typically occurs with the natural menstrual cycle of a woman because the ectopic endometrial tissue is still hormonally active. Therefore, this tissue will naturally shed with the withdrawal of progesterone after the breakdown of the corpus luteum.[5] However, unlike normal hematomas, such as those seen in the ovary with ovulation, these are lined with sticky endometrial stroma and glands and contain more fibrous tissue. Therefore, these are more commonly seen with adhesions present in surrounding areas, which can cause significant pain for the patient and create various challenges for the surgeon during surgical resection of an endometrioma.[6]

When discussing the etiology of endometriomas, it is always appropriate to mention the etiology of endometriosis as well, since this is the foreshadowing condition of an endometrioma. However, the etiology of endometriosis is a controversial discussion in the medical community. The oldest and most widely accepted theory for developing endometriosis is retrograde menstruation. This theory suggests that endometriosis develops from the endometrial tissue traveling in a retrograde manner through the fallopian tubes and into the pelvis during a woman’s natural menstrual cycle. This tissue then travels and seeds in different areas, creating the endometriosis lesions. Some of these lesions may seed in an ovary and begin the process of forming an endometrioma, as discussed above.[7]

This theory of retrograde menstruation likely contributes to the development of endometriosis. However, most people in the medical community feel that it is more of a multifactorial development. For instance, it is difficult to believe this theory in women with distant endometriosis lesions or pre-pubescent females with endometriosis. Therefore, other theories that have been suggested include the theory of metaplasia. This theory suggests that extrauterine cells undergo metaplasia and transdifferentiate into endometrial cells. Another prominent theory is that viable endometrial cells get seeded via the hematogenous and lymphatic spread. No one theory has been fully proven, and it is likely a combination of these theories mentioned above.[8]

Epidemiology

Endometriosis, in general, has been found to affect approximately 10% of women of reproductive age. However, only about 3% of reproductive-aged women have clinically significant disease.[9] Among this 3%, there are specific populations in which endometriosis is quite prevalent. For example, endometriosis has been found in nearly 50% of women experiencing issues with infertility and nearly 70% of women with pelvic pain.[10][11]

There is limited data when looking specifically at the prevalence of endometriomas. However, it is estimated that 17 to 44% of women with endometriosis experience an endometrioma,[12][13] and 28% of these women will have bilateral endometriomas.[14] In the specific subfertility population, approximately 17% of these women are found to have endometriomas.[15]

There is also limited data to suggest specific risk factors for endometriomas alone.[16] However, there are known general risk factors for the development of endometriosis.

These include:

- Nulliparity

- Early menarche (typically before 11 to 13 years old)[17]

- Late menopause, short menstrual cycles (less than 27 days)[18]

- Heavy menstrual bleeding[18]

- Mullerian anomalies[19]

- Height greater than 68 inches[20]

- Low body mass index (BMI)[18]

- Consumption of high amounts of trans unsaturated fat[21]

- Exposure to diethylstilbestrol in utero[22]

In addition to risk factors for endometriosis, endometriosis also increases other patient risks. Many of these have been previously discussed, such as infertility, chronic pelvic pain, dyschezia, dyspareunia, and dysmenorrhea. However, it has also been found that women with endometriosis have an increased risk for certain types of ovarian cancer. The overall risk of ovarian cancer remains low. However, multiple studies have demonstrated women with endometriosis have a higher incidence of clear cell and endometrioid ovarian cancer.[23] There was one study in particular from Finland, which only found this increased risk in women who had endometriomas.[24]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of endometriomas is the same as endometriosis in general since endometriomas are a subset of this more extensive medical condition. The pathway for this disease process occurs with the hormonal response of the ectopic endometrial tissue. This tissue responds to the cyclical hormonal changes of a woman’s menstrual cycle in the same way that the intrauterine endometrium does. It will become proliferative, secretory, and slough just as it would if it were within the uterus. With these fluctuations comes varying concentrations of cytokines and prostaglandin molecules.

Cytokines and prostaglandins are signaling molecules for creating an inflammatory response and thus generate inflammation in the area of the endometriotic implantation. This inflammatory response then lays the foundation for the production of new vascularization and new fibrous tissue formation. This snowball effect then creates the adhesions and pain commonly associated with this disease process. These issues also lead to the main complications of this disease, such as infertility and chronic pelvic pain. Patients with endometriomas have a more severe disease state and typically experience this on a more significant scale than those with stage one or two endometriosis.[9][25][26]

Histopathology

The only way to confirm the diagnosis of endometriosis, including endometriomas, is to surgically diagnose it using direct visualization and tissue samples. The biopsy must contain both endometrial glands and stroma to confirm the presence of endometriosis in the tissue.[27]

History and Physical

History

In general, patients with symptomatic endometriosis are frequently nulliparous females of reproductive age with a chief complaint of heavy or painful menses. Their periods will often last longer than seven days. They may complain of chronic pelvic pain, pain with sexual intercourse, or defecation (see a full list of symptoms below). Their periods are typically regular, though they may have shorter menstrual cycles (less than 27 days). The onset of pain for these patients is typically 2 or 3 days prior to the onset of their menses, and the pain typically begins to resolve a couple of days after their menses has started.[1]

Endometriomas can cause severe pain. They are most commonly found on the ovaries, and the pain is typically isolated to the side of the lesion. However, depending on the extent of their disease and the laterality of their lesions, patients may experience bilateral or generalized pain. If an ovarian endometrioma ruptures, the thick endometrial fluid can spill throughout the abdomen and cause significant pain and inflammation. These patients often present with an acute surgical abdomen.[28]

Although endometriomas are most commonly found on the ovaries, it is important to remain vigilant with patients that come in with complaints of pain. Endometriomas have been found in other unsuspecting places. For example, there are many documented cases of endometriomas being present within abdominal surgical incision scars. Endometrial implants have also been documented within the lung parenchyma and the brain. Therefore, if a patient complains of cyclical pain during their menstrual cycles, endometriosis is something to keep in mind, regardless of where the pain is located.[2][29]

Symptoms

- Pelvic pain

- Heavy menses

- Painful menses

- Back pain

- Painful sexual intercourse (dyspareunia)

- Painful defecation (dyschezia)

- Painful urination (dysuria)

- Urinary frequency

- Nausea/vomiting

- Bloating[30]

Physical

Endometriosis, including those with endometriomas, typically has minimal findings on physical exams. Endometriomas, if large enough, could be felt on a bimanual exam. However, apart from this, these patients have few abnormal findings. You will often find generalized pelvic tenderness or tenderness in the affected area. However, this can also be sensitive to the timing of the exam with respect to the patient’s menstrual cycle. The patient will often have more pain if the exam is completed just before the onset of her menses compared to if it was done just after her menses were completed. Other possible findings on the bimanual exam include a fixed or retroverted uterus, suggesting scarring secondary to endometriosis. At times, nodularity of the uterosacral ligaments can also be palpated.[31][32][33]

However, patients who present after an endometrioma rupture could demonstrate an acute abdomen upon evaluation. Findings in these cases include peritoneal signs such as abdominal rigidity, rebound pain, and involuntary guarding.[28]

Evaluation

Endometriomas can often be visualized on imaging. However, they appear similar to other cystic lesions on imaging, and final pathology is only discovered through surgery. If these findings are not seen on imaging, the diagnosis becomes even more elusive. It is important to remember that the definitive diagnosis of endometriosis is made through surgical visualization of the lesions. Therefore, there is no diagnostic test that can be done. However, there are a limited number of tests that can be used as a tool to assist with the diagnosis.

Laboratory evaluations that can be considered for these patients include a complete blood count (CBC), cancer antigen (CA)-125, CCR1, urinalysis, and sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing. The CBC can help guide the concern for infection and anemia. If there is an elevated white blood cell count, the suspicion of an infectious cause of the patient’s pelvic pain would be higher. The hemoglobin can also help guide you to the level of blood loss, as these patients typically have heavier periods and may be anemic as a result. CA-125 can become elevated in women with endometriosis. However, this is a non-specific marker and is not routinely ordered.[1] It is also important to complete urinalysis to rule out a urinary tract infection from the differential diagnosis, as well as STD testing such as cervical cultures for gonorrhea and chlamydia to rule out these infections.

When it comes to imaging, a transvaginal ultrasound is commonly ordered for these patients to determine if there is a cause for their pelvic pain that can be visualized. Superficial implants of endometriosis cannot be seen on ultrasound or any other imaging modality. However, ultrasound is often where endometriomas are found. Endometriomas typically appear as simple cysts. However, they can also be seen as multi-loculated cysts or cystic-solid lesions. The typical appearance of these lesions on ultrasound shows low-level homogenous echos, otherwise described as a ground-glass appearance. This is consistent with old hemorrhagic debris. These lesions are also typically devoid of any vascularity when examined with doppler flow.[34][35]

Other imaging modalities that can be considered are magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT). MRI has shown a higher sensitivity for detecting a pelvic mass than ultrasonography. However, due to the cost of an MRI, the benefit does not outweigh the financial burden; thus, ultrasound is more commonly used. Like ultrasound, MRI is limited in detecting diffuse pelvic endometriosis and may only be beneficial for finding endometriomas.[35] CT scan exposes the patient to radiation, and although it may identify a pelvic mass, the characteristics of the mass on CT scan do provide good clues as to the type of mass it is. Therefore, a CT scan is not the ideal imaging modality for these patients.

The gold standard for the diagnosis of endometriosis is via laparoscopy. Because imaging and laboratory studies are of limited benefit in diagnosing endometriosis, direct visualization through surgery is the standard. During laparoscopy, endometriosis lesions will typically appear blue or black. However, they can appear as red, white, or non-pigmented lesions. At this time, the severity of the disease can also be evaluated. If there are significant adhesions, peritoneal defects, or endometriomas present, this is indicative of a more severe disease. The visualized lesions can be biopsied and evaluated by pathology for endometrial glands and stroma.[36] If the patient is also experiencing infertility issues, chromotubation can also be completed at this time to assess tubal patency.

Laparoscopy is an important procedure in patients with endometriosis because it is both diagnostic and therapeutic, especially in cases with endometriomas. This is an integral part of treatment for these patients with refractory endometriosis or patients with symptomatic endometriomas.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of endometriosis mainly consists of hormonal medications or surgical treatment. Milder forms of endometriosis are treatable with oral contraceptive pills, various forms of progesterone (oral pill, intrauterine device), gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists (such as leuprolide), or androgens (such as danazol).[37][38][39] However, once a patient’s endometriosis has become severe enough to have the presence of an endometrioma, surgical management is typically preferred. GnRH agonists have been shown to decrease the size of endometriomas. However, patients have not reported any difference in their pain.[40][41][42][43] Therefore, this option is typically abandoned for patients with endometriomas.(A1)

Surgical treatment of endometriosis can range from more conservative approaches to more radical approaches based on the patient’s symptoms and desire for future fertility. Conservative surgery consists of the destruction of endometrial lesions (typically with laser or cautery), drainage of the endometrioma, and removal of the cystic capsule.[44] However, if a patient’s pain is severe and they do not desire future fertility, some patients undergo total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy as a more definitive treatment.(B2)

Surgeries, especially more conservative options, are typically completed laparoscopically. In surgical resection of an endometrioma, it is important to strip the cyst wall during the procedure instead of simply draining the cyst. This has been shown to decrease recurrence rates.[44] If a patient is having difficulties with fertility, resection of an endometrioma has been shown to improve natural pregnancy rates.[45](B2)

The main issue with surgical endometrioma resection, especially in women experiencing infertility and considering in-vitro fertilization (IVF), is whether it affects the amount of ovarian reserve. Women have been shown to have a lower AMH (anti-mullerian hormone) level after cystectomy, which is a hormone used by fertility specialists to measure ovarian reserve.[46] There has also been a reported 2 to 3% of patients having ovarian failure after resection of bilateral endometriomas.[47] Therefore, these are important risks to consider when choosing whether surgery is appropriate for each patient, given their fertility desires. Due to this limited data, if patients are already being seen by a fertility specialist and IVF is being considered, endometriomas are most often managed expectantly. The exception is in cases of severe symptoms or issues with egg retrieval caused by endometrioma.[48](A1)

After surgery, some providers place patients on medical therapy to attempt to prevent a recurrence. There have been studies that show a 6-month course of oral contraceptive pills helps to prevent a recurrence. However, this treatment option again depends on the patient and whether or not they are trying to conceive.[49][50](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

When evaluating patients with suspected endometriomas, it is essential to consider all possible conditions. Given the ambiguous presentation of endometriomas and endometriosis, it can present similarly to other conditions.[18]

Often, these patients present with vague pelvic pain. Therefore, important conditions to keep on your differential are other sources of pelvic pain. These include:

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Appendicitis

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Ovarian torsion

- Diverticulitis

- Urinary tract infection

- An ovarian cyst (other than endometrioma)

- Sexually transmitted infections (gonorrhea, chlamydia)

If an adnexal mass is present and known from imaging, there are characteristics of the mass that can indicate what kind of adnexal mass it is. As discussed in the evaluation section above, endometriomas have a characteristic ground glass appearance on ultrasound. These findings are also similarly seen in hemorrhagic cysts, and often the diagnosis between the two is not made until the time of surgery. Therefore, when dealing with imaging evidence of endometriomas, it is vital to consider hemorrhagic cysts in the differential diagnosis.[51]

Also, when a patient presents with an acute abdomen, and there is a concern for a ruptured endometrioma, the most important things to keep in mind are ruptured ectopic pregnancy and ovarian torsion. These are all surgical emergencies that must be taken to the operating room as soon as possible.

Surgical Oncology

Endometriomas carry a small risk of developing a malignancy, specifically epithelial ovarian cancers. However, that risk appears low. A meta-analysis of 13 studies and approximately 9000 women with epithelial ovarian cancers showed that a self-reported history of endometriosis was three times as high.[52]

There may be a gene activation of KRAS and PI3K associated with ovarian cancer and a history of endometriomas. In addition, genes such as PTEN and ARID1A have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of cancer in such lesions.[53] However, on their own, these lesions are not considered premalignant, and no staging workup or screening is required.

Staging

There are four stages of endometriosis described by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. The stages are minimal, mild, moderate, and severe. Staging is completed surgically, most commonly via laparoscopy.[25][26]

- Stage I (minimal): Small solitary lesions without significant adhesions

- Stage II (mild): Superficial lesions less than 5 cm, without significant adhesions

- Stage III (moderate): Multiple deep implants, small endometriomas unilaterally or bilaterally on the ovaries, and thin adhesions

- Stage IV (severe): Multiple deep implants, large endometriomas unilaterally or bilaterally on the ovaries, thick adhesions

As can be seen by these descriptions, if an endometrioma is present, the patient is already a stage 3 or 4. Most patients are found to have stage 1 or 2 endometriosis. However, staging does not always coincide with the severity of symptoms.[26]

Prognosis

The overall prognosis for patients with endometriosis is favorable. This is a benign disease. However, it is a chronic condition and can be progressive. Patients with endometriomas signify those with more severe disease and thus can have more long-term complications from the disease. Even if treatment is effective for patients for a time, it is, unfortunately, a condition with a high level of reoccurrence. Therefore, the main issue of this disease is the lack of truly definitive treatment, which can cause long-term issues such as pain and infertility. Thankfully, most women have an improvement in their symptoms once they become menopausal due to the lack of cyclical hormonal signaling.[1]

Complications

The two main complications of endometriomas are the same as endometriosis in general. These complications, as discussed in this article, include chronic pelvic pain and infertility. In addition, if the endometrioma is 6 cm or large, this puts the patient at increased risk for ovarian torsion, which is a surgical emergency and can lead to loss of the ovary.[9] Women with endometriosis have an increased risk for certain types of ovarian cancer, and endometriomas carry a small risk of upgrading to malignancy. However, the risk of these is very low.

Deterrence and Patient Education

When caring for patients with endometriomas, it is important to discuss the expectations for treatment and possible complications of having endometriosis. Endometriomas are treated using laparoscopic surgery. Therefore, the patient must receive education on the risks and benefits of laparoscopic surgery before undergoing a laparoscopic cystectomy. It is also important that the patient understand that endometriomas develop from endometriosis, a chronic condition. The patient should be advised that approximately 25% of women experience a reoccurrence of an endometrioma. Apart from reoccurrence, the patient may also experience issues with fertility and chronic pelvic pain related to their underlying endometriosis, which may require further treatment.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Because endometriosis and endometriomas are part of a chronic condition that has the potential to be widespread in the body, an interprofessional team approach utilizing the expertise of clinicians (MDs, DOs, NPs, and PAs) is essential. The treating clinician must make the diagnosis and decide the course of treatment, including the need for any referrals. Nurses are also critically important team members who can offer patient counsel, perform monitoring, take histories, and report any findings or concerns to the clinician. Since medications are an important part of treatment for patients with more mild forms of endometriosis that do not yet have a cystic component to their disease or do not want surgery, it is important to discuss these treatments with a pharmacist who can help determine the ideal duration and drug to provide these patients with the best relief.[37] Pharmacists will also perform medication reconciliation, verify dosing, and counsel patients on medication administration and potential adverse events. Any interprofessional team member who notes a change in the patient's condition, therapeutic failure, or an adverse event must document their findings in the patient's medical record and promptly notify appropriate team members to enact corrective measures. These examples of interprofessional teamwork demonstrate how this paradigm can improve patient outcomes for endometriomas and related conditions.

When initially evaluating these patients, most often, a pelvic ultrasound is performed. It is crucial when looking at any adnexal masses to describe them appropriately. There are specific characteristics of endometriomas that raise suspicion when evaluating the images. Therefore, radiologists play an important role in diagnosis. This also helps answer the question of whether or not surgery is most appropriate for each patient. Radiologists can also help indicate whether or not other structures are involved, which is extremely important if surgery does occur.[35]

Endometriosis can lead to multiple adhesions and endometriosis implants. These lesions can, at times, involve the bowel or the bladder. In severe disease, there may be bowel obstructions or ureteral involvement.[54][55] In these cases, general surgery or urology may need to be involved in completing the necessary surgical procedures.

If patients do opt for surgical treatment, which is often the case for endometriomas, additional team members come together to provide appropriate care for the patient. Anesthesiologist evaluation of the patient for proper anesthesia is important to assist with a smooth surgery and good post-operative pain control. Nursing care in both the pre-operative and post-operative periods is important to give the patient the appropriate medications at the right time. Finally, pharmacy assistance for appropriate post-op pain control also has an important role in the ideal care of the patient.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Vercellini P, Viganò P, Somigliana E, Fedele L. Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nature reviews. Endocrinology. 2014 May:10(5):261-75. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.255. Epub 2013 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 24366116]

Meggyesy M, Friese M, Gottschalk J, Kehler U. Case Report of Cerebellar Endometriosis. Journal of neurological surgery. Part A, Central European neurosurgery. 2020 Jul:81(4):372-376. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1701622. Epub 2020 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 32221961]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceExacoustos C, De Felice G, Pizzo A, Morosetti G, Lazzeri L, Centini G, Piccione E, Zupi E. Isolated Ovarian Endometrioma: A History Between Myth and Reality. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2018 Jul-Aug:25(5):884-891. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.12.026. Epub 2018 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 29353008]

Hwu YM, Wu FS, Li SH, Sun FJ, Lin MH, Lee RK. The impact of endometrioma and laparoscopic cystectomy on serum anti-Müllerian hormone levels. Reproductive biology and endocrinology : RB&E. 2011 Jun 9:9():80. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-80. Epub 2011 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 21651823]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBrosens IA, Puttemans PJ, Deprest J. The endoscopic localization of endometrial implants in the ovarian chocolate cyst. Fertility and sterility. 1994 Jun:61(6):1034-8 [PubMed PMID: 8194613]

Kawaguchi T, Kushibe K, Kimura M, Takahama M, Tojo T, Enomoto Y, Nonomura A, Taniguchi S. Outcome of surgical intervention for isolated intrathoracic lymph node metastasis from infradiaphragmatic malignancy: report of two cases. Annals of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery : official journal of the Association of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgeons of Asia. 2006 Oct:12(5):358-61 [PubMed PMID: 17095980]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLiu DT, Hitchcock A. Endometriosis: its association with retrograde menstruation, dysmenorrhoea and tubal pathology. British journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 1986 Aug:93(8):859-62 [PubMed PMID: 3741813]

Rizner TL. Estrogen metabolism and action in endometriosis. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2009 Aug 13:307(1-2):8-18. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.03.022. Epub 2009 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 19524121]

Bulun SE. Endometriosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2009 Jan 15:360(3):268-79. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804690. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19144942]

Eskenazi B, Warner ML. Epidemiology of endometriosis. Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America. 1997 Jun:24(2):235-58 [PubMed PMID: 9163765]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLaufer MR, Goitein L, Bush M, Cramer DW, Emans SJ. Prevalence of endometriosis in adolescent girls with chronic pelvic pain not responding to conventional therapy. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology. 1997 Nov:10(4):199-202 [PubMed PMID: 9391902]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJenkins S, Olive DL, Haney AF. Endometriosis: pathogenetic implications of the anatomic distribution. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1986 Mar:67(3):335-8 [PubMed PMID: 3945444]

Redwine DB. Ovarian endometriosis: a marker for more extensive pelvic and intestinal disease. Fertility and sterility. 1999 Aug:72(2):310-5 [PubMed PMID: 10439002]

Vercellini P, Aimi G, De Giorgi O, Maddalena S, Carinelli S, Crosignani PG. Is cystic ovarian endometriosis an asymmetric disease? British journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 1998 Sep:105(9):1018-21 [PubMed PMID: 9763055]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBarnhart K, Dunsmoor-Su R, Coutifaris C. Effect of endometriosis on in vitro fertilization. Fertility and sterility. 2002 Jun:77(6):1148-55 [PubMed PMID: 12057720]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKavoussi SK, Odenwald KC, As-Sanie S, Lebovic DI. Incidence of ovarian endometrioma among women with peritoneal endometriosis with and without a history of hormonal contraceptive use. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2017 Aug:215():220-223. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.06.028. Epub 2017 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 28651149]

Treloar SA, Bell TA, Nagle CM, Purdie DM, Green AC. Early menstrual characteristics associated with subsequent diagnosis of endometriosis. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2010 Jun:202(6):534.e1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.857. Epub 2009 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 20022587]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBallard KD, Seaman HE, de Vries CS, Wright JT. Can symptomatology help in the diagnosis of endometriosis? Findings from a national case-control study--Part 1. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2008 Oct:115(11):1382-91. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01878.x. Epub 2008 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 18715240]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMissmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Malspeis S, Willett WC, Hunter DJ. Reproductive history and endometriosis among premenopausal women. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2004 Nov:104(5 Pt 1):965-74 [PubMed PMID: 15516386]

Hediger ML, Hartnett HJ, Louis GM. Association of endometriosis with body size and figure. Fertility and sterility. 2005 Nov:84(5):1366-74 [PubMed PMID: 16275231]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMissmer SA, Chavarro JE, Malspeis S, Bertone-Johnson ER, Hornstein MD, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Willett WC, Hankinson SE. A prospective study of dietary fat consumption and endometriosis risk. Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 2010 Jun:25(6):1528-35. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq044. Epub 2010 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 20332166]

Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Michels KB, Hunter DJ. In utero exposures and the incidence of endometriosis. Fertility and sterility. 2004 Dec:82(6):1501-8 [PubMed PMID: 15589850]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePearce CL, Templeman C, Rossing MA, Lee A, Near AM, Webb PM, Nagle CM, Doherty JA, Cushing-Haugen KL, Wicklund KG, Chang-Claude J, Hein R, Lurie G, Wilkens LR, Carney ME, Goodman MT, Moysich K, Kjaer SK, Hogdall E, Jensen A, Goode EL, Fridley BL, Larson MC, Schildkraut JM, Palmieri RT, Cramer DW, Terry KL, Vitonis AF, Titus LJ, Ziogas A, Brewster W, Anton-Culver H, Gentry-Maharaj A, Ramus SJ, Anderson AR, Brueggmann D, Fasching PA, Gayther SA, Huntsman DG, Menon U, Ness RB, Pike MC, Risch H, Wu AH, Berchuck A, Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. Association between endometriosis and risk of histological subtypes of ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis of case-control studies. The Lancet. Oncology. 2012 Apr:13(4):385-94. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70404-1. Epub 2012 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 22361336]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSaavalainen L, Lassus H, But A, Tiitinen A, Härkki P, Gissler M, Pukkala E, Heikinheimo O. Risk of Gynecologic Cancer According to the Type of Endometriosis. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2018 Jun:131(6):1095-1102. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002624. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29742675]

Schliep KC, Chen Z, Stanford JB, Xie Y, Mumford SL, Hammoud AO, Boiman Johnstone E, Dorais JK, Varner MW, Buck Louis GM, Peterson CM. Endometriosis diagnosis and staging by operating surgeon and expert review using multiple diagnostic tools: an inter-rater agreement study. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2017 Jan:124(2):220-229. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13711. Epub 2015 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 26435386]

. Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996. Fertility and sterility. 1997 May:67(5):817-21 [PubMed PMID: 9130884]

Clement PB. The pathology of endometriosis: a survey of the many faces of a common disease emphasizing diagnostic pitfalls and unusual and newly appreciated aspects. Advances in anatomic pathology. 2007 Jul:14(4):241-60 [PubMed PMID: 17592255]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePratt JH, Shamblin WR. Spontaneous rupture of endometrial cysts of the ovary presenting as an acute abdominal emergency. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1970 Sep 1:108(1):56-62 [PubMed PMID: 5465884]

Sanada T, Park J, Hagiwara M, Ikeda N, Nagai T, Matsubayashi J, Saito K. CT and MRI findings of bronchopulmonary endometriosis: a case presentation. Acta radiologica open. 2018 Sep:7(10):2058460118801164. doi: 10.1177/2058460118801164. Epub 2018 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 30288301]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHansen KE, Kesmodel US, Baldursson EB, Kold M, Forman A. Visceral syndrome in endometriosis patients. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2014 Aug:179():198-203. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.05.024. Epub 2014 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 24999078]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMounsey AL, Wilgus A, Slawson DC. Diagnosis and management of endometriosis. American family physician. 2006 Aug 15:74(4):594-600 [PubMed PMID: 16939179]

Kennedy S, Bergqvist A, Chapron C, D'Hooghe T, Dunselman G, Greb R, Hummelshoj L, Prentice A, Saridogan E, ESHRE Special Interest Group for Endometriosis and Endometrium Guideline Development Group. ESHRE guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 2005 Oct:20(10):2698-704 [PubMed PMID: 15980014]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKingsberg SA, Janata JW. Female sexual disorders: assessment, diagnosis, and treatment. The Urologic clinics of North America. 2007 Nov:34(4):497-506, v-vi [PubMed PMID: 17983890]

Young SW, Groszmann Y, Dahiya N, Caserta M, Yi J, Wasson M, Patel MD. Sonographer-acquired ultrasound protocol for deep endometriosis. Abdominal radiology (New York). 2020 Jun:45(6):1659-1669. doi: 10.1007/s00261-019-02341-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31820046]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNoventa M, Scioscia M, Schincariol M, Cavallin F, Pontrelli G, Virgilio B, Vitale SG, Laganà AS, Dessole F, Cosmi E, D'Antona D, Andrisani A, Saccardi C, Vitagliano A, Ambrosini G. Imaging Modalities for Diagnosis of Deep Pelvic Endometriosis: Comparison between Trans-Vaginal Sonography, Rectal Endoscopy Sonography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. A Head-to-Head Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2019 Dec 17:9(4):. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics9040225. Epub 2019 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 31861142]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDuffy JM, Arambage K, Correa FJ, Olive D, Farquhar C, Garry R, Barlow DH, Jacobson TZ. Laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014 Apr 3:(4):CD011031. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011031.pub2. Epub 2014 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 24696265]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGuzick DS, Huang LS, Broadman BA, Nealon M, Hornstein MD. Randomized trial of leuprolide versus continuous oral contraceptives in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pelvic pain. Fertility and sterility. 2011 Apr:95(5):1568-73. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.01.027. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21300339]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHull ME, Moghissi KS, Magyar DF, Hayes MF. Comparison of different treatment modalities of endometriosis in infertile women. Fertility and sterility. 1987 Jan:47(1):40-4 [PubMed PMID: 2947817]

Schlaff WD, Dugoff L, Damewood MD, Rock JA. Megestrol acetate for treatment of endometriosis. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1990 Apr:75(4):646-8 [PubMed PMID: 2314784]

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Treatment of pelvic pain associated with endometriosis: a committee opinion. Fertility and sterility. 2014 Apr:101(4):927-35. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.02.012. Epub 2014 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 24630080]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, Calhaz-Jorge C, D'Hooghe T, De Bie B, Heikinheimo O, Horne AW, Kiesel L, Nap A, Prentice A, Saridogan E, Soriano D, Nelen W, European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 2014 Mar:29(3):400-12. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det457. Epub 2014 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 24435778]

Chapron C, Vercellini P, Barakat H, Vieira M, Dubuisson JB. Management of ovarian endometriomas. Human reproduction update. 2002 Nov-Dec:8(6):591-7 [PubMed PMID: 12498427]

Alborzi S, Zarei A, Alborzi S, Alborzi M. Management of ovarian endometrioma. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2006 Sep:49(3):480-91 [PubMed PMID: 16885655]

Hayasaka S, Ugajin T, Fujii O, Nabeshima H, Utsunomiya H, Yokomizo R, Yuki H, Terada Y, Murakami T, Yaegashi N. Risk factors for recurrence and re-recurrence of ovarian endometriomas after laparoscopic excision. The journal of obstetrics and gynaecology research. 2011 Jun:37(6):581-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01409.x. Epub 2010 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 21159045]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePorpora MG, Pallante D, Ferro A, Crisafi B, Bellati F, Benedetti Panici P. Pain and ovarian endometrioma recurrence after laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis: a long-term prospective study. Fertility and sterility. 2010 Feb:93(3):716-21. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.018. Epub 2008 Dec 4 [PubMed PMID: 19061997]

Raffi F, Metwally M, Amer S. The impact of excision of ovarian endometrioma on ovarian reserve: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2012 Sep:97(9):3146-54. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1558. Epub 2012 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 22723324]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBusacca M, Riparini J, Somigliana E, Oggioni G, Izzo S, Vignali M, Candiani M. Postsurgical ovarian failure after laparoscopic excision of bilateral endometriomas. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2006 Aug:195(2):421-5 [PubMed PMID: 16681984]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHart RJ, Hickey M, Maouris P, Buckett W. Excisional surgery versus ablative surgery for ovarian endometriomata. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2008 Apr 16:(2):CD004992. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004992.pub3. Epub 2008 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 18425908]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVercellini P, DE Matteis S, Somigliana E, Buggio L, Frattaruolo MP, Fedele L. Long-term adjuvant therapy for the prevention of postoperative endometrioma recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2013 Jan:92(1):8-16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01470.x. Epub 2012 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 22646295]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSeracchioli R, Mabrouk M, Manuzzi L, Vicenzi C, Frascà C, Elmakky A, Venturoli S. Post-operative use of oral contraceptive pills for prevention of anatomical relapse or symptom-recurrence after conservative surgery for endometriosis. Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 2009 Nov:24(11):2729-35. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep259. Epub 2009 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 19625310]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePatel MD, Feldstein VA, Filly RA. The likelihood ratio of sonographic findings for the diagnosis of hemorrhagic ovarian cysts. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2005 May:24(5):607-14; quiz 615 [PubMed PMID: 15840791]

Wang C, Liang Z, Liu X, Zhang Q, Li S. The Association between Endometriosis, Tubal Ligation, Hysterectomy and Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: Meta-Analyses. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2016 Nov 14:13(11): [PubMed PMID: 27854255]

Prat J, D'Angelo E, Espinosa I. Ovarian carcinomas: at least five different diseases with distinct histological features and molecular genetics. Human pathology. 2018 Oct:80():11-27. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2018.06.018. Epub 2018 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 29944973]

Endo Y, Akatsuka J, Obayashi K, Takeda H, Hayashi T, Nakayama S, Suzuki Y, Hamasaki T, Kondo Y. Efficacy of Laparoscopic Partial Cystectomy with a Transurethral Resectoscope in Patients with Bladder Endometriosis: See-Through Technique. Urologia internationalis. 2020:104(7-8):546-550. doi: 10.1159/000503795. Epub 2020 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 32191941]

Lam K, Lang E. Endometriosis as a rare cause of small bowel obstruction. ANZ journal of surgery. 2020 Nov:90(11):E137-E138. doi: 10.1111/ans.15916. Epub 2020 Apr 27 [PubMed PMID: 32339367]