Introduction

The diaphragm separates the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity. It is a double-domed, musculotendinous partition that consists of a continuous sheet of muscle surrounding a central tendon. The peripheral muscle is named according to its peripheral points of attachment. The sternal part attaches to the posterior aspect of the xiphoid process. The coastal part attaches to the internal surfaces of the inferior six costal cartilages. Finally, the lumbar part attaches to the medial and lateral arcuate ligaments, as well as, the three most superior lumbar vertebrae.[1][2]

The diaphragm is centrally and peripherally attached. The three peripheral attachments include:

- Xiphoid process of the sternum

- Lumbar vertebrae and arcuate ligament

- Coastal cartilages of ribs 7 to 10 and direct attachment to ribs 11 to 12.

The segments of the diaphragm that evolve from the vertebrae are known as the left and right crura.

The diaphragm separates the abdominal and thoracic cavities but does allow certain structures to pass through via its three openings:

The inferior vena cava passes through the diaphragm at the vena caval foramen. This aperture is located in the central tendon at the level of T8. Sometimes the phrenic nerve may also be found passing through this aperture. The esophageal hiatus is located in the muscular aspect of the diaphragm near the right crus. It is located at the level of T10. The posterior and anterior vagal nerves are also found passing through this hiatus. Finally, the aortic hiatus is located between the two crura at the level of T12. The thoracic duct and azygos vein pass through the aortic hiatus.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The diaphragm is the major muscle of inspiration, and respiration for that matter, as expiration is a passive movement. When the diaphragm contracts, it descends inferiorly into the abdominal cavity, which results in an increase in intrathoracic volume. This also leads to an increased vertical diameter of the chest cavity, which results in lowered intrathoracic pressure. When the diaphragm relaxes, it ascends causing a decrease in intrathoracic volume and consequently, a rise in intrathoracic pressure.

Embryology

The diaphragm develops during the third week of embryogenesis. It is formed by transverse and longitudinal folding. It is a composite structure that is formed from the following four components: the septum transversum, the pleuroperitoneal membranes, the dorsal mesentery of the esophagus (megaesophagus), and muscular ingrowths from lateral body walls. The septum transversum is the primitive central tendon. It grows dorsally from the ventrolateral body wall and is composed of mesodermal tissue. It expands to fuse with the pleuroperitoneal membranes and the dorsal mesentery of the esophagus. Additionally, the crura of the diaphragm develop from myoblasts surrounding the megaesophagus.

The septum transversum forms in the cervical region opposite to the third, fourth and fifth cervical somites; therefore, during the migration of the fifth embryonic week, the myoblasts from this region bring their nerve fibers with them. This accounts for the circuitous route of the phrenic nerve from the upper cervical vertebrae inferiorly to innervate the diaphragm.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply to the diaphragm is from the superior phrenic, musculophrenic, inferior phrenic, pericardiacophrenic, and lower internal intercostal arteries. The superior phrenic arteries arise from the thoracic aorta. The musculophrenic and pericardiacophrenic arteries are both branches of the internal thoracic artery. The inferior phrenic arteries often arise from the anterior trunk of the aorta above the celiac artery.

The venous drainage of the diaphragm includes the brachiocephalic veins, azygos veins, and the smaller tributaries of both the inferior vena cava and the left suprarenal vein.

Nerves

The diaphragm is innervated largely by the phrenic nerve. The phrenic nerve is composed of fibers from cervical nerves C3, C4, and C5. A helpful mnemonic for remembering the phrenic nerve's composition and innervation is “C3, 4, and 5 help to keep the diaphragm alive.” While the phrenic nerve is the chief supply of motor innervation to the diaphragm, it also supplies sensory information to the central tendon. The inferior most six intercostal nerves and the subcostal nerve supply the sensory afferent information of the peripheral portions of the diaphragm. Clinically, if the phrenic nerve is damaged, the diaphragm will appear floppy and remain elevated.[4]

Physiologic Variants

The peripheral attachments of the diaphragm can sometimes vary and rarely the defect may result in laxity of the diaphragm or even herniation.

Clinical Significance

Diaphragmatic paralysis is known to occur when there is an injury to the phrenic nerve. This injury may occur in the neck, brainstem or on the diaphragm. While trauma is a common cause of injury to the phrenic nerve, today most unilateral cases of phrenic nerve injury occur as a result of open-heart surgery. In rare cases, the phrenic nerve may be compressed by a lesion in the chest. The diaphragm itself may be involved in myasthenia gravis. Diabetic neuropathy may also be a cause of bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis.[5][6]

Paralysis of the diaphragm produces paradoxical movement. In most young people with no lung pathology, unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis is well tolerated. In people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema or another lung disease, unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis may produce symptoms even with mild exertion. The initial diagnosis of diaphragmatic paralysis is often suspected on an incidental chest x-ray.

Bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis is usually always symptomatic, and the patient may be symptomatic even at rest. Lung function studies will usually reveal a restrictive defect. When diaphragmatic paralysis is diagnosed, the treatment depends on symptoms. Asymptomatic patients may be observed. The underlying causes should be treated. In children, diaphragmatic plication is often done, but the procedure is not helpful in adults. For bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis, a permanent tracheostomy was commonly done in the past. However, today one can pace the diaphragm with good outcomes.

Other Issues

The two hernias associated with the diaphragm include a sliding and paraesophageal hernia. Hernias can also occur as a result of congenital malformations and almost always require surgery. The congenital diaphragmatic hernia is usually on the left side and occurs through the posterior lumbosacral triangle. This allows the abdominal contents to pass into the chest cavity and impair the development of the lungs. The diaphragm may also be injured as a result of blunt trauma resulting in rupture and herniation of the abdominal contents.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

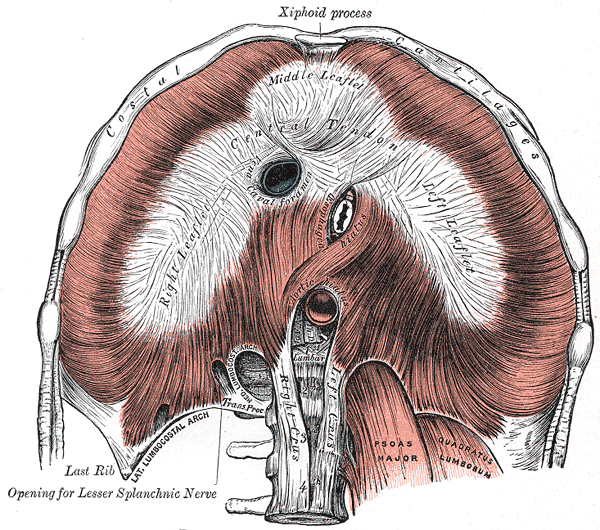

Diaphragm Central Tendon. This illustration shows the diaphragm's central tendon, xiphoid process, costal cartilages, central tendon, opening for lesser splanchnic nerve, psoas major, quadratus lumborum, vena cava foramen, esophageal hiatus, and aortic hiatus.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

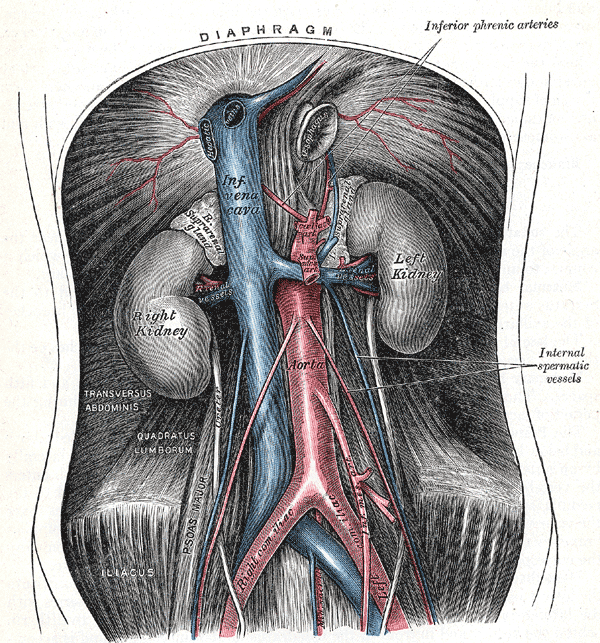

Retroperitoneal Organs. This image shows the anatomical relationships between the diaphragm, right and left suprarenal glands, right and left gonadal vessels, celiac trunk, superior and inferior mesenteric arteries, inferior phrenic arteries, internal spermatic vessels, median sacral arteries, left and right kidneys, inferior vena cava, abdominal aorta, right and left renal vessels, transversus abdominis, quadratus lumborum, right and left common Iliac vessels, psoas major, and iliacus.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Kassem MM, Wallen JM. Esophageal Perforation and Tears. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30335331]

Verlinden TJM, van Dijk P, Herrler A, de Gier-de Vries C, Lamers WH, Köhler SE. The human phrenic nerve serves as a morphological conduit for autonomic nerves and innervates the caval body of the diaphragm. Scientific reports. 2018 Aug 3:8(1):11697. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30145-x. Epub 2018 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 30076368]

Sefton EM, Gallardo M, Kardon G. Developmental origin and morphogenesis of the diaphragm, an essential mammalian muscle. Developmental biology. 2018 Aug 15:440(2):64-73. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.04.010. Epub 2018 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 29679560]

Goyal N,Jain A, Variant communication of phrenic nerve in neck. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2018 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 30361840]

Lim KH, Park J. Blunt traumatic diaphragmatic rupture: Single-center experience with 38 patients. Medicine. 2018 Oct:97(41):e12849. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012849. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30313123]

Caleffi-Pereira M, Pletsch-Assunção R, Cardenas LZ, Santana PV, Ferreira JG, Iamonti VC, Caruso P, Fernandez A, de Carvalho CRR, Albuquerque ALP. Unilateral diaphragm paralysis: a dysfunction restricted not just to one hemidiaphragm. BMC pulmonary medicine. 2018 Aug 2:18(1):126. doi: 10.1186/s12890-018-0698-1. Epub 2018 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 30068327]