Introduction

Dacryostenosis is an acquired or congenital condition resulting from nasolacrimal duct obstruction (NLDO), which causes epiphora or watery eyes. The term "dacryostenosis" is derived from the Greek words dákryon ("tear") and stenósis ("narrowing"), which refers to the congenital or acquired narrowing of the nasolacrimal duct. The ocular surface remains consistently moistened by tears produced by specialized lacrimal glands. After nourishing the ocular surface, these tears flow into the nose through the nasolacrimal duct.

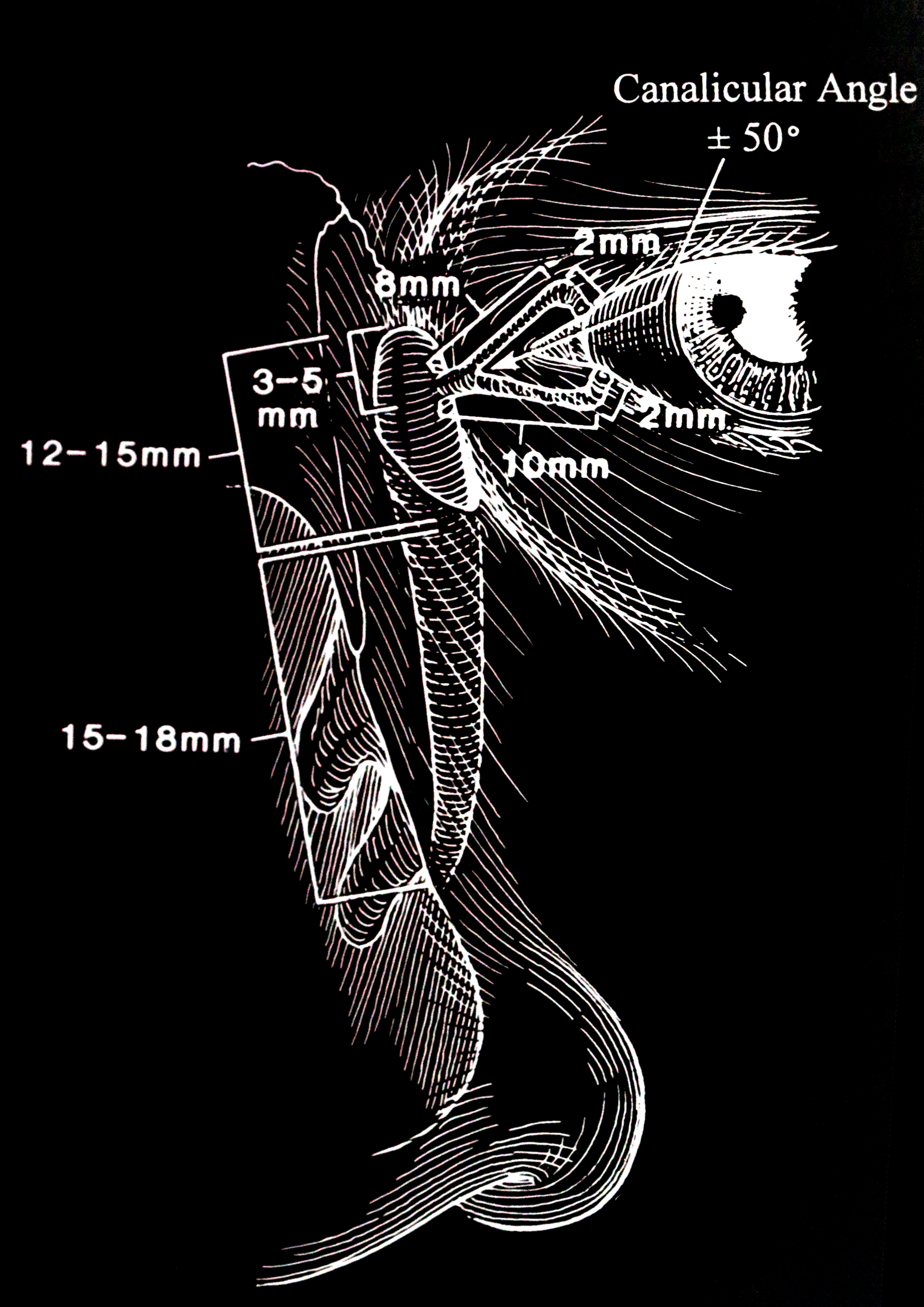

The secretory lacrimal system relies on the integral function of the lacrimal glands. When addressing dacryostenosis, it is essential to grasp the mechanisms of tear production and the anatomy of the tear drainage system (see Image. The Lacrimal Drainage Pathway).[1][2] The 4 key anatomical components that constitute the excretory system are listed below.

- The puncta: These are orifices situated on the surface of eyelids.

- The canaliculi: These are small channels connecting the puncta with the nasolacrimal sac.

- The nasolacrimal sac: This serves as a reservoir for tears that overflow.

- The nasolacrimal duct: This carries tears from the eyes into the nasal cavity.[3][4][5][6][7]

Epiphora is a condition that results from anomalies affecting any part of the excretory system and causing excessively watery eyes and an overflow of tears.[8]

The congenital form of dacryostenosis is the most prevalent cause of persistent tearing and ocular discharge, affecting nearly 6% of all infants. This condition results from abnormal canalization of the nasolacrimal duct, in utero, at the end closest to the nose.[9]

In contrast, the acquired form of dacryostenosis can be classified as either primary or secondary, depending on the underlying cause. The causes of primary acquired NLDO (PANDO) include inflammation, fibrosis, mucosal edema, vascular congestion, stasis, infections, or trauma to the lacrimal apparatus, which can result in partial or total obstruction of the duct later in life.[10] Menstrual hormonal changes, osteoporosis, and the gradual narrowing of the lacrimal duct, particularly in females older than 40, contribute to increased susceptibility. Other potential underlying factors include infections, inflammation, neoplasms, and mechanical obstruction.

The presence of a mucoid discharge and persistent tearing are the 2 classic clinical symptoms of dacryostenosis.[8] These symptoms typically appear in newborns during the first few weeks to months of life. Although dacryostenosis is generally benign, untreated cases can advance to recurrent conjunctivitis and dacryocystitis, potentially causing various complications such as stained tears, frequent eye infections, preseptal or orbital cellulitis, sepsis, meningitis, or brain abscess in both children and adults. Therefore, it is crucial to address dacryostenosis promptly to prevent the onset of severe medical problems.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of dacryostenosis is multifaceted, involving both inherited and acquired etiologies. Congenital forms result from anatomical anomalies or abnormalities associated with the development of the nasolacrimal system. Acquired etiologies include infections, inflammation, medication, or damage to the lacrimal system.

Congenital Dacryostenosis

Although congenital dacryostenosis is typically sporadic, recent studies have revealed the influence of genetics in its development. Current research establishes connections between specific gene alterations and the formation of the lacrimal system, providing insight into the molecular causes and the potential links to other congenital syndromes.[11][12] In addition, prematurity and maternal drug use may also increase the risk of congenital dacryostenosis.

Acquired Dacryostenosis

The etiology of acquired dacryostenosis is multifactorial and not fully understood. Although most cases are categorized as involutional or idiopathic, potential underlying causes include trauma, neoplasm, systemic disease, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy are some potential underlying causes.[13]

Primary Acquired Dacryostenosis

PANDO refers to disorders in the drainage system of the tear glands and is induced by certain factors such as inflammation, fibrosis, mucosal edema, vascular congestion, stasis, infections, or trauma to the lacrimal apparatus. These factors may lead to partial or total obstruction of the duct later in life.

According to some authors, the primary cause of PANDO is the anatomical narrowing of the bony lacrimal canal, which occurs as individuals age. Specifically, women tend to have a smaller diameter of the lacrimal duct, which tends to narrow further with time and aligns with osteoporotic changes in the body.[14] Hormonal changes associated with menstruation cause a generalized de-epithelialization within the lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct, leading to an obstruction caused by sloughed-off debris. These anatomical changes related to hormonal fluctuations and osteoporotic changes may explain the higher incidence of NLDO in women older than 40 compared to men.[10]

Chronic inflammation can lead to changes in the blood vessels of the vascular plexus surrounding the lacrimal sac and fibrosis of the connective tissue fibers near the lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct.[15] The onset of swelling of the mucous membrane, remodeling of the helical arrangement of connective tissue fibers, malfunctions in the subepithelial cavernous body with reactive hyperemia, and temporary occlusion of the lacrimal passage can all result from ascending or descending inflammation originating from the nose, frontal anatomic structures like the ethmoid sinuses, or the eye.[16] Certain authors suggest that the cause may be ascending inflammation from the region of the nose and sinus cavities.[17] Clinical studies indicate that nasal disease is sporadic in patients undergoing dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR).[10]

Secondary Acquired Dacryostenosis

Secondary acquired dacryostenosis (SANDO) can result from various causes such as infection, inflammation, neoplasm, trauma, and mechanical disorders.

Infection: Dacryocystitis stands out as the most prevalent infectious cause of SANDO. The primary bacterial species involved are Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Actinomyces. A descending infection from the conjunctiva is an additional potential cause.

Inflammation: Inflammatory causes of NLDO include granulomatosis with polyangiitis, sarcoidosis, cicatricial pemphigoid, sinus histiocytosis, Kawasaki disease, scleroderma, anti-glaucoma drops, radiation, systemic chemotherapy, bone marrow transplantation, iodine-131 (I-131) for thyroid carcinoma, and docetaxel therapy for metastatic breast cancer and non–small cell lung cancer.[18][19][20][21]

Neoplasm: Neoplasms causing NLDO can be primary tumors, secondary spread, or metastatic disease.[22] The most common secondary spread occurs from eyelid carcinomas, ethmoid sinus, maxillary antrum, and nasopharyngeal tumors.[23] Primary tumors are typically adenoid cystic carcinoma, eccrine spiradenoma, and small B-cell lymphoma. Metastatic lesions are not common, but there are case reports that document the occurrence of metastases from breast and prostate cancer.

Trauma: Traumatic causes of NLDO include naso-orbital-ethmoidal fractures, blunt facial trauma from motor vehicle collisions, delayed treatment of facial fractures, scarring after lacrimal probing, complications of orbital decompression surgery, and occurrences following paranasal or nasal surgery.[22]

Mechanical disorders: Obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct can result from intraluminal foreign bodies such as dacryoliths or rhinoliths, nasal foreign bodies, or mucoceles. Dacryoliths can result from infections caused by Actinomyces or Candida spp, as well as prolonged use of topical medications. Recent evidence indicates a shift to infections with Staphylococcus and Streptococcus spp in Asia.[24][25]

Epidemiology

Congenital dacryostenosis is a prevalent condition, impacting approximately 6% of all newborns.[26] This condition is the leading cause of persistent tearing and ocular discharge in infants, arising from abnormal canalization of the nasolacrimal system in utero. A study indicates that 20% of healthy infants encounter challenges with lacrimal drainage at some point during their first year of life.[27] NLDO occurs more frequently in premature infants and infants with Down syndrome, with incidences of 16% and 22% to 36%, respectively.[28] In addition, studies indicate a significantly higher prevalence of congenital dacryostenosis in infants delivered by cesarean section.[29] Anisometropia is observed in approximately 10% of neonates with dacryostenosis.[30]

Acquired obstruction of the lacrimal drainage system, leading to symptoms such as epiphora, punctal discharge, and medial canthal swelling, is a common ophthalmic complaint, accounting for approximately 3% of office visits in some series, with an annual incidence of 37 cases per 100,000.[31][32] The obstruction is more frequently found at the level of the nasolacrimal duct or puncta and less frequently at the level of the canaliculi. Acquired obstruction tends to occur more frequently in women older than 40.[32][33]

Pathophysiology

Congenital Dacryostenosis

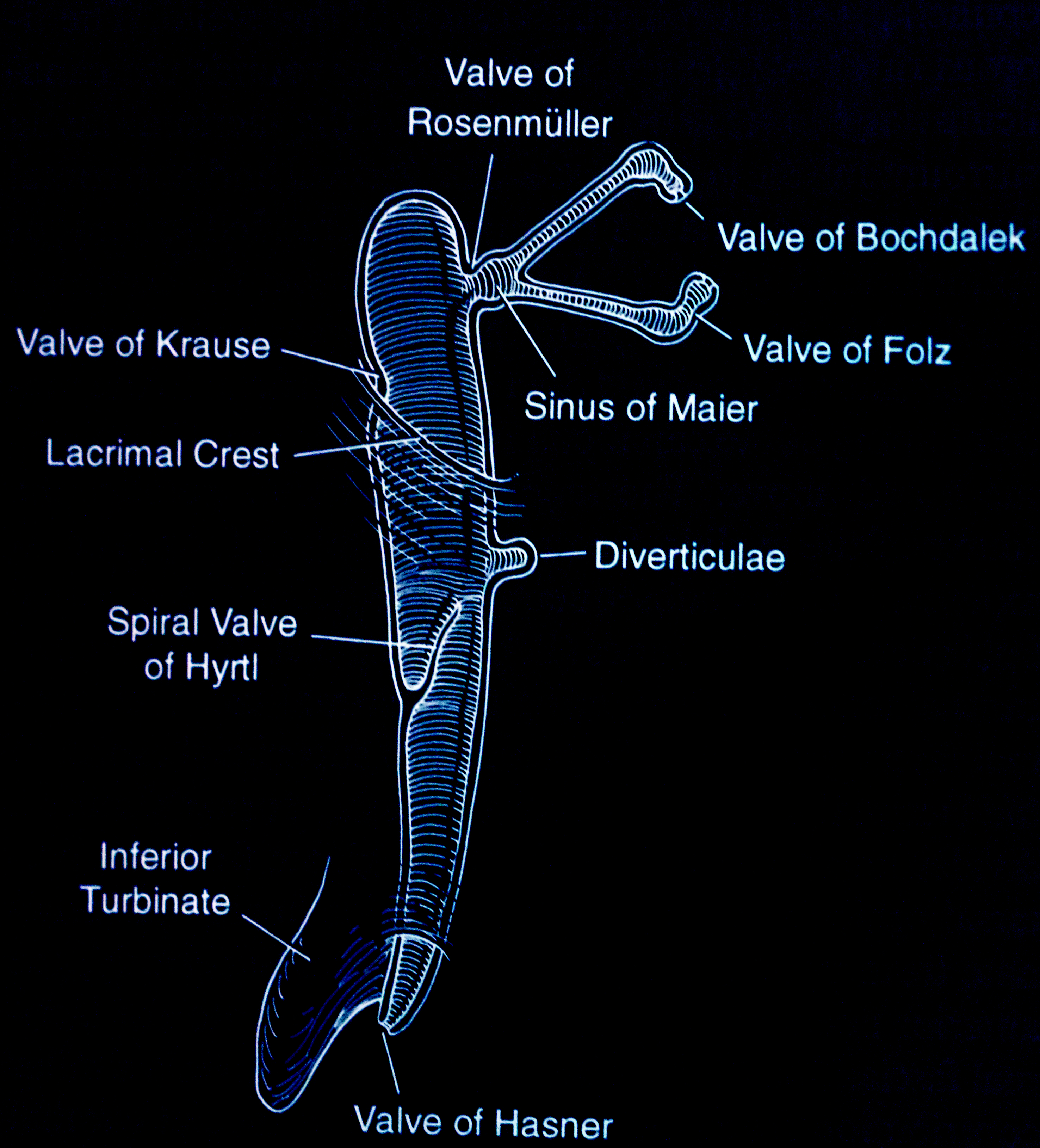

The nasolacrimal apparatus forms during embryonic development between the third and the fifth week. Canalization begins in the third month, with full canalization typically complete between the eyelid and the nose by the eighth month of gestation. Obstruction arises due to the persistence of an embryonal membrane or abnormalities in bone development, leading to symptoms such as excess tearing, mucoid discharge, and debris or "mattering" on the eyelids.[29] The most common physical cause of congenital dacryostenosis is a mechanical obstruction located in the distal portion of the nasolacrimal duct near the valve of Hasner, where the nasolacrimal duct enters the nose.[34][35] Rarely, the obstruction may occur closer to the nasolacrimal sac near the valve of Rosenmüller, often resulting in a watery discharge (see Image. Valves and Sinuses).[36]

The normal anatomy of the nasolacrimal system comprises puncta, canaliculi, common canaliculi, lacrimal sac, and nasolacrimal duct. The nasolacrimal duct opens at the inferior meatus over the Hasner valve. Infants with stenosis of the inferior meatus, incomplete canalization at the distal end of the nasolacrimal duct, and any bony abnormality causing a narrow inferior bony nasolacrimal canal may exhibit symptoms of dacryostenosis.

Acquired Dacryotenosis

As discussed earlier, acquired dacryostenosis may result from infection, inflammation, neoplasms, trauma, or mechanical obstruction. Dacryocystitis, chronic conjunctivitis, and blepharitis may be due to bacterial, fungal, or viral causes.[37][38] Bacteria are typically present in the conjunctiva and nasal mucosa. When tears stagnate, there is a risk of developing dacryocystitis. Repeated episodes of dacryocystitis can result in alterations to the structural epithelial and subepithelial cells. Notably, the loss of typical goblet and epithelial cells is crucial in the mechanism of tear outflow.

Chronic inflammation can induce fibrosis of the connective tissue fibers in the lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct region, leading to the loss of blood vessels in the cavernous body and contributing to the malfunction of tear outflow.[10] Persistent inflammation associated with blepharitis results in keratinization around the punctum walls, overgrowth of the conjunctival epithelium, and the formation of inflammatory membranes, ultimately causing duct obstruction. These conditions can increase the likelihood of developing punctal stenosis. Dry eye syndrome, which may be associated with persistent blepharitis, might contribute to punctal stenosis. Neoplasms, trauma, and mechanical issues can all lead to SANDO through direct obstruction, compression, or scarring resulting from the underlying problem.

Histopathology

The histopathology of infants with congenital dacryostenosis often indicates a lack of underlying canalicular tissue. Biopsy specimens from patients with acquired dacryostenosis frequently exhibit signs of inflammatory infiltrates, fibrosis, chronic inflammation, and capillary proliferation. Chronic dacryocystitis, presenting as nongranulomatous inflammation, is the most prevalent histopathological diagnosis observed in examined specimens of lacrimal sacs obtained during DCR.[39]

History and Physical

Congenital Dacryostenosis

Epiphora is the predominant presenting symptom in the majority of dacryostenosis cases. Caregivers of affected infants may report chronic or intermittent tears and mattering. They may also observe "stress epiphora" or increased tearing when exposed to the wind, cold, or during times of nasal obstruction.

Healthcare professionals should gather patient information related to pregnancy and prematurity history, family history of NLDO or congenital glaucoma, history of other congenital anomalies, and history of tearing and photophobia to evaluate for neonatal glaucoma.

Expected examination findings: These findings include an increase in the size of the tear meniscus, debris on the eyelashes, reflux of tears or mucoid discharge onto the eye through the puncta on palpation of the lacrimal sac, and minimal erythema of the lower eyelid.[40][41]

Deviations from the above findings, such as erythema, purulent discharge, bluish swelling of the skin overlying the lacrimal sac, photophobia, corneal clouding, or large or asymmetric corneal diameters, suggest alternative diagnoses such as infection, dacryocystocele, or glaucoma. Infants experiencing obstructions in both the proximal and distal portions of the nasolacrimal duct may develop a congenital dacryocystocele.[42] Furthermore, the distal obstruction is likely to be localized to the valve of Hasner. However, the proximal obstruction may occur at the valve of Rosenmüller or the common canaliculus. Although less common, congenital dacryocystoceles may be associated with potentially severe complications.

Acquired Dacryostenosis

Epiphora is the most common presenting symptom in patients with acquired dacryostenosis. Other concerns may be a mucoid or purulent discharge, recurrent conjunctivitis or dacryocystitis, painful swelling at the medial canthus, or possibly epistaxis in patients with tumors involving the nose, sinuses, or lacrimal sac. Clinicians should inquire about any history of eye surgery, glaucoma, trauma, systemic illness, chemotherapy, or topical medications.

Potential examination findings: These findings may include overflow of tears, tenderness or a palpable mass over the lacrimal sac or medial canthal area, and mucoid or purulent eye discharge upon massaging the lacrimal sac.

The lumen of the duct may progressively decrease, potentially leading to complete closure and dilation of the lacrimal sac. Clinically, a bulge of the medial canthus resulting from the enlarged lacrimal sac is a typical sign of chronic dacryostenosis.[43] Mucous secretions are frequently visible coming from the lacrimal puncta after slight pressure of the medial canthal swelling.

Infection of the lacrimal sac contents by bacterial, fungal, or viral organisms can lead to acute dacryocystitis.[44] Symptoms such as redness, pain, pulsation, epiphora, and tightness in the medial lid angle, accompanied by a severe headache, prompt patients to seek medical advice.[45] Chronic mucous membrane inflammation can occur if the obstruction remains unresolved, resulting in recurring acute episodes.

Evaluation

Diagnosis of Dacryostenosis

The diagnosis of dacryostenosis is typically clinical based on the patient's history and physical examination. Clinicians may opt to conduct diagnostic testing if uncertainty exists regarding diagnosing dacryostenosis in patients. Available diagnostics tests for dacryostenosis are listed below.

Fluorescein dye disappearance test (FDDT): During the test, the clinician will drop topical anesthetic and fluorescein dye into each eye of the patient and wipe the excess tears. To ensure accurate results, the patient should avoid rubbing their eyes, and the tears on their cheeks should be untouched. The clinician should recheck the patient after 5 minutes. Usually, it is expected that the dye should drain into the nose within this timeframe if the lacrimal drainage system has no obstruction. In case of obstruction, a large amount of the dye persists or escapes over the lower eyelid and down the cheek.[46]

Dacryocystography: This diagnostic test involves injecting a contrast agent into the lacrimal system, allowing conventional radiography to visualize the location of the obstruction and aiding in the formulation of a surgical plan. Furthermore, high-resolution imaging techniques in magnetic resonance dacryocystography provide precise anatomical information.[47][48]

Dacryoscintigraphy: This procedure is more sensitive and less invasive than dacryocystography. Dacryoscintigraphy is also more sensitive in detecting incomplete blocks of the upper drainage system. However, its anatomical imaging is less detailed compared to dacryocystography.

Imaging tools: Imaging tools such as computed tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), high-frequency ultrasound, and optical coherence tomography can serve as valuable noninvasive techniques for evaluating lacrimal structures. CT scans are particularly useful in excluding tumors in the lacrimal passage or pathological changes in the nose or sinuses. Moreover, CT scans are instrumental in assessing septal deviation, hypertrophy of the turbinates, sinusitis, and concha bullosa, which can aggravate the symptoms of lacrimal stenosis and help determine a surgical approach.[49] Nevertheless, routine screening with CT is not recommended by experts due to the associated risks of radiation exposure.[50]

If a tumor of the lacrimal system or the sinuses is suspected, an MRI with gadolinium is considered more informative than a CT scan. High-frequency ultrasound can be beneficial in pediatric patients.[51] As there is no single reliable method for testing the patency of the lacrimal drainage system, physicians should refer to various complementary tests in a clinical setting.[52][53]

Lacrimal duct irrigation: In lacrimal duct irrigation, the clinician inserts a cannula into the puncta and canaliculi, performing saline irrigation. Diagnostic confirmation of dacryostenosis or a common canalicular obstruction is indicated by complete reflux from the opposite punctum of the same eye.[54]

Additional Diagnostic Tests

Tear production: Clinicians can test tear production to determine the cause of epiphora, including tear deficiency or instability and reflex tearing (see Image. Causes of Epiphora).

Schirmer test: The Schirmer test measures the quantity of tears the eye produces to maintain moisture.

- Without a topical anesthetic, after 5 minutes, the standard measurement for wetting the Schirmer strip is between 10 and 30 mm.

- With topical anesthesia, after 5 minutes, the standard measurement for wetting the Schirmer strip is >5 mm.

Tear break-up time test: The standard tear break-up time is 15 to 30 seconds. An abnormal break-up time of 10 seconds or less indicates a tear abnormality leading to reflex tearing.

Probing of canaliculi: When a clinician encounters an obstruction during lacrimal duct irrigation, they can use a lacrimal probe to palpate or localize the site of obstruction and subsequently measure it using a Bowman lacrimal probe.

Laboratory Studies

Clinicians should order the following laboratory tests as clinically indicated, depending on the patient's condition.

- KOH if suspected fungal infection

- Gram or Geimsa stain

- Culture and sensitivity

- Anti-topoisomerase I (anti-Scl-70) antibody to evaluate for scleroderma

- Anti-RNA polymerase III antibody to evaluate for scleroderma

- Anticytoplasmic antibodies in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Lacrimal sac biopsy

Treatment / Management

Nonoperative Treatment

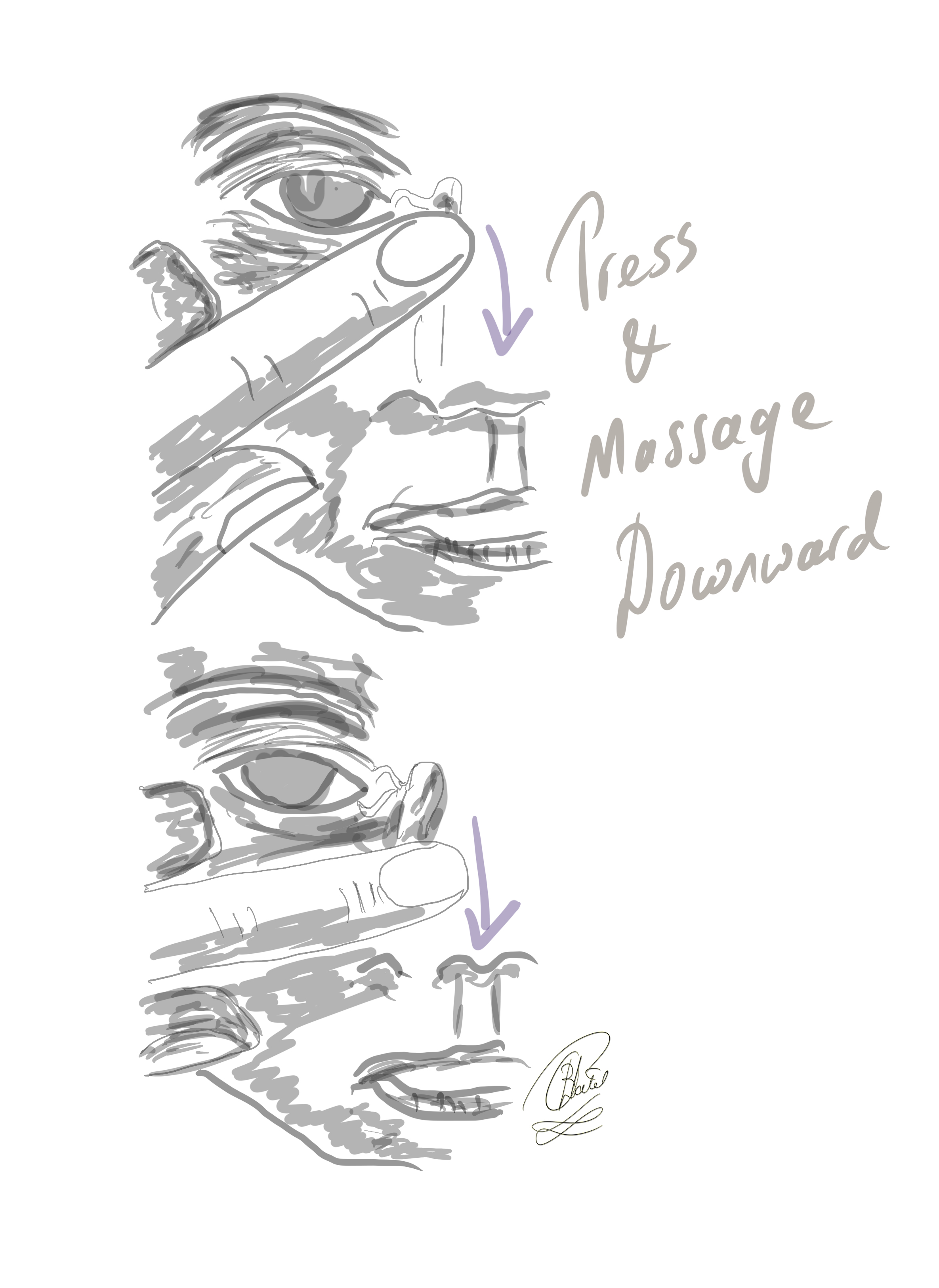

In nearly 90% of infants, symptoms related to blocked tear ducts can be resolved through conservative traetment measures, such as gentle massage of the lacrimal duct area, within the first year.[55][56] Treatment involves performing Crigler lacrimal sac compression or lacrimal sac massages (see Image. The Crigler Maneuver for Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction).[57] Caregivers should apply moderate downward pressure over the lacrimal sac 2 to 3 times daily.[58] Antibacterial ointment may be prescribed to avoid bacterial infection.[59] However, if the symptoms persist beyond 6 to 10 months, referring the infant to an ophthalmologist for a comprehensive eye examination is advisable. The ophthalmologist will assess for anisometropia during the eye examination, which can occur in approximately 10% of patients with congenital NLDO, and consider the need for nasolacrimal duct probing.(A1)

Operative Treatment

Lacrimal duct probing: In cases where the obstruction persists beyond 6 to 12 months, clinicians can opt for lacrimal duct probing.[60] The ophthalmologist inserts a small blunt probe or irrigation cannula into the punctum, advances it until it abuts the obstruction, and then gently progresses through the obstruction until reaching the nasal cavity. To ensure patency, irrigation with fluorescein-stained saline is performed.[61] Clinicians perform lacrimal duct probing in the office with local anesthesia or in the operating room with general anesthesia. Children who are 12 months or older typically require general anesthesia.

The ideal age for conducting probing remains a matter of debate among clinicians. Some prefer to conduct probing in children between 6 and 10 months, whereas others choose to wait until 12 months, considering that most cases tend to resolve entirely by this age. Early probing has advantages such as avoiding general anesthesia, a shorter duration of symptoms, and a reduced risk of lacrimal duct scarring. Conversely, delaying the procedure allows more time for spontaneous resolution and the potential for a more definitive intervention in the operating room, especially for children aged 12 months and older who are likely to require general anesthesia.

Nasolacrimal intubation: The combination of probing and irrigation is an easy, quick procedure with a high success rate.[26] This technique involves implanting a silicone stent after nasolacrimal duct probing. Indications for nasolacrimal intubation include the presence of significant stenosis of the distal end of the nasolacrimal duct, children who fail an initial probing attempt, or children undergoing general anesthesia for lacrimal duct probing. A silicone stent is placed in the nasolacrimal system and removed in the office after 2 to 6 months.[62] (B2)

Balloon dacryoplasty: Balloon dacryoplasty, also known as balloon dilation, is a simple and minimally invasive technique used to address incomplete obstruction of the lacrimal drainage system and for patients who have not responded to probing and irrigation procedures. Typically, surgeons leave a stent in place after the procedure.[63]

Dacryocystorhinostomy: DCR is a more complex procedure that requires the removal of a part of the lacrimal bone to create a window between the lacrimal sac and the nasal cavity.[64][65] DCR aims to maintain the active drainage mechanism. This procedure can be performed with both external access and endoscopic nasal access, with endoscopic access typically requiring general anesthesia. Clinicians perform transcanalicular laser-assisted DCR by inserting a small laser fiber into the canaliculi under local anesthesia. This approach involves less tissue removal than standard techniques, but the success rate is lower when compared to standard DCR techniques.[66] Some authors suggest that applying the antimetabolite mitomycin-C at the time of DCR increases the functional and anatomic success.[67](A1)

Conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy: Patients with significant anatomic abnormalities proximal to the lacrimal sac, chemical burns, irradiation, paralysis of the lacrimal pump, absence or obliteration of canaliculi, and tumors of the lacrimal sac may require conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy. This procedure bypasses the lacrimal drainage by inserting a Pyrex glass tube or Jones tube between the caruncle and the nasal cavity (see Image. Jones Tests).[68] Periodic removal and cleaning of the Jones tube, followed by immediate replacement, may be necessary.[63] This procedure relies on gravity for drainage. Patients have tolerated this device for at least 4 decades.[69] (A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The potential differential diagnoses for dacryostenosis include conjunctivitis, blepharitis, conjunctival foreign bodies, corneal abrasion, corneal ulcer, keratitis, congenital glaucoma, dacryocystitis, anatomical abnormalities, nasal lacrimal duct cyst, allergic conjunctivitis, trichiasis, infantile hemangioma of the lacrimal sac area, posttraumatic lid and orbit abnormalities, tumors affecting the lacrimal sac, nasal obstruction due to deviated septum or nasal polyps, uveitis, and dacryocystocele.

Prognosis

In children, spontaneous resolution is frequent and occurs by 6 to 12 months in approximately 90% of patients.[27] Spontaneous resolution is unlikely if the obstruction persists for more than 12 months.[27] In adults with acquired dacryostenosis, spontaneous resolution is rare. The prognosis depends on the technique and associated conditions when surgery is necessary.

In children, nasolacrimal duct intubation has success rates of 90% to 96% when used for primary treatment and 84% when performed after failed probing.[62] For adults, the results reveal a 77% success rate for complete resolution of symptoms, a 96% success rate at 2 years, and an 85% success rate at 3 years.[70] Balloon dacryoplasty is successful in 82% of cases when used for primary treatment and 77% when performed after failed probing. Success rates of external and internal DCR are similar and reported to be more than 95% in most studies. The endoscopic approach may be preferred because it allows the surgeon to identify and correct intranasal abnormalities, which are the most common causes of DCR failure.[71]

Complications

Dacryostenosis can progress to chronic conjunctivitis and dacryocystitis, and if left untreated, it can lead to complications such as endophthalmitis, meningitis, brain abscesses, and orbital cellulitis.[72] Signs and symptoms of acute dacryocystitis include erythema, swelling, warmth, tenderness of the lacrimal sac, and purulent discharge. Approximately 10% of children with NLDO may develop anisometropia, with or without amblyopia.[73] In rare cases, lacrimal fistulas can form in the presence of chronic inflammation.[74] Other potential complications include scarring of the nasolacrimal duct following surgical intervention, adverse reactions to anesthesia, and infections resulting from the surgical procedure.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Congenital dacryostenosis results from an incomplete canalization of the nasolacrimal duct during development. Neoplasms, trauma, radiation, chemotherapy, mechanical obstruction, and inflammation can cause acquired NLDO. The primary symptom in all patients with dacryostenosis is epiphora or watery eyes. Healthcare professionals should educate patients and caregivers about the normal lacrimal drainage process, followed by a detailed discussion of the patient's level of obstruction. Although clinical diagnosis is often sufficient for newborns and infants, adults may require additional diagnostic tests such as dacryocystography, dacryoscintigraphy, CT, MRI, and nasal endoscopy for a more comprehensive evaluation of the condition.

Patients and caregivers should recognize the significance of contacting their healthcare team if they experience erythema, purulent drainage, pain, or headache. These signs may indicate infection and prompt treatment is essential to prevent severe consequences such as cellulitis, meningitis, and brain abscess.

Surgical treatment options with high success rates are available. Most infants experience complete symptom resolution by 12 months with lacrimal duct massage. Surgical intervention for infants is considered by ophthalmologists starting at 6 to 7 months. Acquired forms in patients are less likely to resolve spontaneously, often necessitating procedures such as nasal lacrimal duct probing, nasal lacrimal duct intubation, DCR, balloon catheter dilation, or, in severe cases, conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Although dacryostenosis is considered a benign condition, it is bothersome and can lead to severe consequences if left untreated. Timely diagnosis is crucial for identifying anisometropia in affected infants, preventing recurrent ocular infections, and avoiding complete stenosis of the puncta or canaliculi. A collaborative approach is essential in providing patient-centered care for individuals with dacryostenosis, thereby reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with this condition.

An interprofessional team of experts from various healthcare departments, including primary care, ophthalmology, radiology, anesthesia, oncology, dermatology, otolaryngology, and advanced practice practitioners, engaged in the care of patients with dacryostenosis should have the necessary knowledge, skills, and competence to diagnose and manage dacryostenosis. This expertise involves distinguishing between congenital and acquired forms and using various diagnostic tests to investigate the underlying causes of acquired dacryostenosis.

A strategic approach using evidence-based treatments is crucial when developing a treatment plan to avoid adverse effects and improve patient outcomes. Each healthcare team member should contribute their expertise and provide seamless interprofessional communication to promote collaborative decision-making. Building a healthcare team based on skill, strategy, and communication will provide patient-centered care, thereby reducing overall morbidity and mortality for patients with dacryostenosis.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Causes of Epiphora. The conditions that can cause epiphora include herpes zoster with keratitis (A), lacrimal mucocele (B), corneal calcific keratopathy (C), floppy eyelid syndrome (D), kissing puncta syndrome (E), and pemphigoid disease with trichiasis and obliteration of puncta (F).

Contributed by BCK Patel, MD, FRCS

(Click Video to Play)

Jones Tests. The video demonstrates how to conduct the Jones tests.

Contributed by BCK Patel, MD, FRCS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Crigler Maneuver for Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction. In this technique, the finger is inwardly pressed against the lacrimal sac, and the massaging movement is directed downward to elevate hydrostatic pressure within the lacrimal sac and the nasolacrimal duct.

Contributed by BCK Patel, MD, FRCS

References

Nair JR, Syed R, Chan IYM, Gorelik N, Chankowsky J, Del Carpio-O'Donovan R. The forgotten lacrimal gland and lacrimal drainage apparatus: pictorial review of CT and MRI findings and differential diagnosis. The British journal of radiology. 2022 Jul 1:95(1135):20211333. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20211333. Epub 2022 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 35522773]

Ali MJ, Paulsen F. Ultrastructure of the lacrimal drainage system in health and disease: A major review. Annals of anatomy = Anatomischer Anzeiger : official organ of the Anatomische Gesellschaft. 2019 Jul:224():1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2019.02.003. Epub 2019 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 30862471]

Ali MJ, Singh S. Optical coherence tomography and the proximal lacrimal drainage system: a major review. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2021 Nov:259(11):3197-3208. doi: 10.1007/s00417-021-05175-3. Epub 2021 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 33861367]

Jang JK, Lee SM, Lew H. A histopathological study of lacrimal puncta in patients with primary punctal stenosis. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2020 Jan:258(1):201-207. doi: 10.1007/s00417-019-04514-9. Epub 2019 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 31713749]

Rishor-Olney CR, Hinson JW. Canalicular Laceration. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32809637]

Juniat V, Lee J, Sia P, Curragh D, Hardy TG, Selva D. High nasolacrimal sac-duct junction anatomical variation - retrospective review of dacryocystography images. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2021 Dec:40(6):505-508. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2020.1817101. Epub 2020 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 32893697]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMaini R, MacEwen CJ, Young JD. The natural history of epiphora in childhood. Eye (London, England). 1998:12 ( Pt 4)():669-71 [PubMed PMID: 9850262]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceUsmani E, Shapira Y, Selva D. Functional epiphora: an under-reported entity. International ophthalmology. 2023 Aug:43(8):2687-2693. doi: 10.1007/s10792-023-02668-4. Epub 2023 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 36952153]

Heichel J, Heindl LM, Struck HG. [Congenital anomalies in lacrimal drainage]. Laryngo- rhino- otologie. 2023 Jun:102(6):423-433. doi: 10.1055/a-1985-1656. Epub 2023 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 37267966]

Paulsen FP, Thale AB, Maune S, Tillmann BN. New insights into the pathophysiology of primary acquired dacryostenosis. Ophthalmology. 2001 Dec:108(12):2329-36 [PubMed PMID: 11733281]

Wang C, Maynard S, Glover TW, Biesecker LG. Mild phenotypic manifestation of a 7p15.3p21.2 deletion. Journal of medical genetics. 1993 Jul:30(7):610-2 [PubMed PMID: 8411039]

Maclean K, Holme SA, Gilmour E, Taylor M, Scheffer H, Graf N, Smith GH, Onikul E, van Bokhoven H, Moss C, Adès LC. EEC syndrome, Arg227Gln TP63 mutation and micturition difficulties: Is there a genotype-phenotype correlation? American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2007 May 15:143A(10):1114-9 [PubMed PMID: 17431922]

Mansur C, Pfeiffer ML, Esmaeli B. Evaluation and Management of Chemotherapy-Induced Epiphora, Punctal and Canalicular Stenosis, and Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2017 Jan/Feb:33(1):9-12. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000745. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27429222]

Janssen AG, Mansour K, Bos JJ, Castelijns JA. Diameter of the bony lacrimal canal: normal values and values related to nasolacrimal duct obstruction: assessment with CT. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2001 May:22(5):845-50 [PubMed PMID: 11337326]

Atkova EL, Astrakhanstev AF, Subbot AM, Yartsev VD. [Dynamic pathomorphological characteristics of the nasolacrimal duct in its stenosis]. Arkhiv patologii. 2023:85(5):22-28. doi: 10.17116/patol20238505122. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37814846]

Heichel J, Struck HG, Hammer T, Viestenz A, Plontke S, Glien A. [Pediatric acute dacryocystitis due to frontoethmoidal mucocele]. HNO. 2019 Jun:67(6):458-462. doi: 10.1007/s00106-019-0671-1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31065761]

Mauriello JA Jr, Palydowycz S, DeLuca J. Clinicopathologic study of lacrimal sac and nasal mucosa in 44 patients with complete acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1992:8(1):13-21 [PubMed PMID: 1554647]

Almeida RA, Narikawa S, Tagliarini JV, Marques ME, Schellini SA. Dacryostenosis due to Paracoccidioides brasiliensis in a patient with an unnoted HIV-1 infection. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 2013 Aug:48(4):e61-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2013.01.011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23931481]

Fonseca FL, Lunardelli P, Matayoshi S. [Lacrimal drainage system obstruction associated to radioactive iodine therapy for thyroid carcinoma]. Arquivos brasileiros de oftalmologia. 2012 Mar-Apr:75(2):97-100 [PubMed PMID: 22760799]

McGwin G Jr, Contorno T, Vicinanzo MG, Owsley C. The Association Between Taxane Use and Lacrimal Disorders. Current eye research. 2023 Sep:48(9):873-877. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2023.2219041. Epub 2023 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 37232564]

Blouin MJ, Black DO, Fradet G. Recurrent dacryostenosis as initial presentation of sarcoidosis. Case reports in otolaryngology. 2012:2012():870527 [PubMed PMID: 22991679]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBecelli R, Renzi G, Mannino G, Cerulli G, Iannetti G. Posttraumatic obstruction of lacrimal pathways: a retrospective analysis of 58 consecutive naso-orbitoethmoid fractures. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2004 Jan:15(1):29-33 [PubMed PMID: 14704558]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKay MD, Morris-Wiseman LF, Beazer A, Winegar BA, Kuo PH. Primary Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction Visualized on (123)I Preablation Scan for Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Journal of nuclear medicine technology. 2020 Mar:48(1):77-78. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.119.235010. Epub 2019 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 31604890]

Kally PM, Omari A, Schlachter DM, Folberg R, Nesi-Eloff F. Microbial profile of lacrimal system Dacryoliths in American Midwest patient population. Taiwan journal of ophthalmology. 2022 Jul-Sep:12(3):330-333. doi: 10.4103/2211-5056.354280. Epub 2022 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 36248083]

Yartsev VD, At Kova EL. [Formation of concrements in the lacrimal excretory system]. Vestnik oftalmologii. 2020:136(6):78-83. doi: 10.17116/oftalma202013606178. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33084283]

Tahat AA. Dacryostenosis in newborns: probing, or syringing, or both? European journal of ophthalmology. 2000 Apr-Jun:10(2):128-31 [PubMed PMID: 10887923]

MacEwen CJ, Young JD. Epiphora during the first year of life. Eye (London, England). 1991:5 ( Pt 5)():596-600 [PubMed PMID: 1794426]

Lorena SH, Silva JA, Scarpi MJ. Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction in premature children. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 2013 Jul-Aug:50(4):239-44. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20130423-01. Epub 2013 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 23614467]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKuhli-Hattenbach C, Lüchtenberg M, Hofmann C, Kohnen T. [Increased prevalence of congenital dacryostenosis following cesarean section]. Der Ophthalmologe : Zeitschrift der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft. 2016 Aug:113(8):675-83. doi: 10.1007/s00347-016-0230-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26906154]

Pyi Son MK, Hodge DO, Mohney BG. Timing of congenital dacryostenosis resolution and the development of anisometropia. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2014 Aug:98(8):1112-5. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304607. Epub 2014 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 24682178]

Heindl LM, Junemann A, Holbach LM. A clinicopathologic study of nasal mucosa in 350 patients with external dacryocystorhinostomy. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2009:28(1):7-11. doi: 10.1080/01676830802414806. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19229737]

Woog JJ. The incidence of symptomatic acquired lacrimal outflow obstruction among residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976-2000 (an American Ophthalmological Society thesis). Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 2007:105():649-66 [PubMed PMID: 18427633]

Perez Y, Patel BC, Mendez MD. Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422468]

Macewen CJ. Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Comprehensive ophthalmology update. 2006 Mar-Apr:7(2):79-87 [PubMed PMID: 16709344]

Moscato EE, Kelly JP, Weiss A. Developmental anatomy of the nasolacrimal duct: implications for congenital obstruction. Ophthalmology. 2010 Dec:117(12):2430-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.030. Epub 2010 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 20656354]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOlitsky SE. Update on congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. International ophthalmology clinics. 2014 Summer:54(3):1-7. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0000000000000030. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24879099]

Pao KY, Yakopson V, Flanagan JC, Eagle RC Jr. Allergic fungal sinusitis involving the lacrimal sac: a case report and review. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2014 Aug:33(4):311-3. doi: 10.3109/01676830.2014.904376. Epub 2014 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 24832182]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRimon A, Hoffer V, Prais D, Harel L, Amir J. Periorbital cellulitis in the era of Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine: predisposing factors and etiologic agents in hospitalized children. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 2008 Sep-Oct:45(5):300-4 [PubMed PMID: 18825903]

Paulsen FP, Schaudig U, Maune S, Thale AB. Loss of tear duct-associated lymphoid tissue in association with the scarring of symptomatic dacryostenosis. Ophthalmology. 2003 Jan:110(1):85-92 [PubMed PMID: 12511351]

Juri Mandić J, Ivkić PK, Mandić K, Lešin D, Jukić T, Petrović Jurčević J. Quality of Life and Depression Level in Patients with Watery Eye. Psychiatria Danubina. 2018 Dec:30(4):471-477. doi: 10.24869/psyd.2018.471. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30439808]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePatel J, Levin A, Patel BC. Epiphora. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491381]

Pur DR, Husein M, Makar I. Management of Congenital Dacryocystocele: A Case Series and Literature Review. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 2023 May:60(3):e31-e34. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20230320-01. Epub 2023 May 1 [PubMed PMID: 37227990]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHeichel J, Struck HG. [Minimally invasive diagnostics and therapy of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction]. Der Ophthalmologe : Zeitschrift der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft. 2017 May:114(5):397-408. doi: 10.1007/s00347-017-0472-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28258301]

Ns VS, N P, Gunabooshanam B, As P, S PK. Cytological Diagnosis Suggesting Candidal Infection of the Nasolacrimal Duct in an Uncontrolled Diabetic Patient With Gingival Abscess. Cureus. 2023 Aug:15(8):e44257. doi: 10.7759/cureus.44257. Epub 2023 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 37772241]

Steinkogler FJ. The postsaccal, idiopathic dacryostenosis--experimental and clinical aspects. Documenta ophthalmologica. Advances in ophthalmology. 1986 Sep 30:63(3):265-86 [PubMed PMID: 3780377]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOzturker C, Purevdorj B, Karabulut GO, Seif G, Fazil K, Khan YA, Kaynak P. A Comparison of Transcanalicular, Endonasal, and External Dacryocystorhinostomy in Functional Epiphora: A Minimum Two-Year Follow-Up Study. Journal of ophthalmology. 2022:2022():3996854. doi: 10.1155/2022/3996854. Epub 2022 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 35369002]

Singh S, Ali MJ, Paulsen F. Dacryocystography: From theory to current practice. Annals of anatomy = Anatomischer Anzeiger : official organ of the Anatomische Gesellschaft. 2019 Jul:224():33-40. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2019.03.009. Epub 2019 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 30954539]

Macri CZ, Shapira Y, Tong J, Hood K, Drivas P, Patel S, Selva D. A Pilot Study of Dynamic Magnetic Resonance Dacryocystography Imaging to Assess Functional Epiphora. Seminars in ophthalmology. 2024 Feb:39(2):158-164. doi: 10.1080/08820538.2023.2256842. Epub 2023 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 37697818]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePapathanassiou S, Koch T, Suhling MC, Lenarz T, Durisin M, Stolle SRO, Raab P. Computed Tomography Versus Dacryocystography for the Evaluation of the Nasolacrimal Duct-A Study With 72 Patients. Laryngoscope investigative otolaryngology. 2019 Aug:4(4):393-398. doi: 10.1002/lio2.293. Epub 2019 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 31453347]

Francis IC, Kappagoda MB, Cole IE, Bank L, Dunn GD. Computed tomography of the lacrimal drainage system: retrospective study of 107 cases of dacryostenosis. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1999 May:15(3):217-26 [PubMed PMID: 10355842]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZhang J, Chen L, Wang QX, Liu R, Zhu WZ, Luo X, Peng L, Xiong W. Diagnostic performance of the three-dimensional fast spin echo-Cube sequence in comparison with a conventional imaging protocol in evaluation of the lachrymal drainage system. European radiology. 2015 Mar:25(3):635-43. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3462-9. Epub 2014 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 25316060]

Kim S, Yang S, Park J, Lee H, Baek S. Correlation Between Lacrimal Syringing Test and Dacryoscintigraphy in Patients With Epiphora. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2020 Jul-Aug:31(5):e442-e445. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000006389. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32282674]

Patel J, Levin A, Patel BC. Epiphora Clinical Testing. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491356]

Kim U, Vardhan A, Datta D, Mekhala A, Kishore N, Rathi G, Hildebrand PL. Regurgitation on pressure over the lacrimal sac versus lacrimal irrigation in determining lacrimal obstruction prior to intraocular surgeries. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2022 Nov:70(11):3833-3836. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1722_22. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36308105]

Pensiero S, Diplotti L, Visalli G, Ronfani L, Giangreco M, Barbi E. Minimally-Invasive Surgical Approach to Congenital Dacryostenosis: Proposal for a New Protocol. Frontiers in pediatrics. 2021:9():569262. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.569262. Epub 2021 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 33681096]

Petersen RA, Robb RM. The natural course of congenital obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 1978 Jul-Aug:15(4):246-50 [PubMed PMID: 739359]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBansal O, Bothra N, Sharma A, Walvekar P, Ali MJ. Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction update study (CUP study): paper I-role and outcomes of Crigler's lacrimal sac compression. Eye (London, England). 2021 Jun:35(6):1600-1604. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-01125-1. Epub 2020 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 32778741]

Kushner BJ. Congenital nasolacrimal system obstruction. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1982 Apr:100(4):597-600 [PubMed PMID: 6896140]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHu K, Patel J, Patel BC. Crigler Technique for Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32644693]

Paul TO, Shepherd R. Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction: natural history and the timing of optimal intervention. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 1994 Nov-Dec:31(6):362-7 [PubMed PMID: 7714699]

Örge FH, Boente CS. The lacrimal system. Pediatric clinics of North America. 2014 Jun:61(3):529-39. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2014.03.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24852150]

Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group, Repka MX, Melia BM, Beck RW, Atkinson CS, Chandler DL, Holmes JM, Khammar A, Morrison D, Quinn GE, Silbert DI, Ticho BH, Wallace DK, Weakley DR Jr. Primary treatment of nasolacrimal duct obstruction with nasolacrimal duct intubation in children younger than 4 years of age. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2008 Oct:12(5):445-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2008.03.005. Epub 2008 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 18595756]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRosen N, Ashkenazi I, Rosner M. Patient dissatisfaction after functionally successful conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy with Jones tube. American journal of ophthalmology. 1994 May 15:117(5):636-42 [PubMed PMID: 8172270]

Van Swol JM, Myers WK, Nguyen SA, Eiseman AS. Revision dacryocystorhinostomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2023 Feb:42(1):1-10. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2022.2109178. Epub 2022 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 35942566]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceUllrich K, Malhotra R, Patel BC. Dacryocystorhinostomy. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32496731]

Patel BC, Phillips B, McLeish WM, Flaharty P, Anderson RL. Transcanalicular neodymium: YAG laser for revision of dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthalmology. 1997 Jul:104(7):1191-7 [PubMed PMID: 9224475]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePhelps PO, Abariga SA, Cowling BJ, Selva D, Marcet MM. Antimetabolites as an adjunct to dacryocystorhinostomy for nasolacrimal duct obstruction. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2020 Apr 7:4(4):CD012309. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012309.pub2. Epub 2020 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 32259290]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEisenbach N, Karni O, Sela E, Nemet A, Dror A, Levy E, Kassif Y, Ovadya R, Ronen O, Marshak T. Conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy (CDCR) success rates and complications in endoscopic vs non-endoscopic approaches: a systematic review. International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2021 Feb:11(2):174-194. doi: 10.1002/alr.22668. Epub 2020 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 32761875]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceScawn RL, Verity DH, Rose GE. Can Lester Jones tubes be tolerated for decades? Eye (London, England). 2018 Jan:32(1):142-145. doi: 10.1038/eye.2017.168. Epub 2017 Aug 18 [PubMed PMID: 28820185]

Moscato EE, Dolmetsch AM, Silkiss RZ, Seiff SR. Silicone intubation for the treatment of epiphora in adults with presumed functional nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2012 Jan-Feb:28(1):35-9. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e318230b110. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22262288]

Lin GC, Brook CD, Hatton MP, Metson R. Causes of dacryocystorhinostomy failure: External versus endoscopic approach. American journal of rhinology & allergy. 2017 May 1:31(3):181-185. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2017.31.4425. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28490404]

Heichel J. [Graduated Treatment Concept for Connatal Dacryostenosis]. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 2017 Oct:234(10):1250-1258. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-100655. Epub 2017 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 28380654]

Piotrowski JT, Diehl NN, Mohney BG. Neonatal dacryostenosis as a risk factor for anisometropia. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2010 Sep:128(9):1166-9. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.184. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20837801]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTel A, Zeppieri M. Congenital Lacrimal Fistula. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 35881736]