Introduction

Crigler-Najjar syndrome is a rare autosomal recessive disorder causing hyperbilirubinemia in newborns. Bilirubin metabolism involves the uptake of bilirubin from circulation, intracellular storage, conjugation with glucuronic acid, and excretion into bile. Abnormalities in any of these processes lead to hyperbilirubinemia. Crigler-Najjar syndrome is characterized by the absence or decreased activity of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT), an enzyme required for glucuronidation of unconjugated bilirubin in the liver. This deficiency is a significant cause of congenital nonhemolytic jaundice.

The syndrome is classified into 2 types based on the level of UGT activity:

- Type 1: Characterized by severe symptoms due to minimal or a complete absence of enzyme activity, individuals with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 (CN1) experience life-threatening and severe jaundice, requiring regular phototherapy for treatment. Patients with this form of the disease are at very high risk of developing neurological complications, including permanent damage such as kernicterus. The only cure for CN1 syndrome is a liver transplant.

- Type 2: This form of Crigler-Najjar syndrome is characterized by milder symptoms resulting from reduced enzyme activity. Individuals with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 (CN2) experience intermittent jaundice triggered by stress and typically manage the condition through conservative measures. Permanent neurological damage is rare in CN2, and the need for a liver transplant is infrequent.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Crigler-Najjar syndrome is caused by an absence or decreased level of the UGT enzyme due to a genetic defect in the bilirubin UDP-glucuronosyltransferase family 1, polypeptide A1 (UGT1A1) gene.[1] In CN1, common mutations include deletions, alterations in intron splice donor and receptor sites, missense mutations, exon skipping, insertions, or the formation of a stop codon within the UGT1A1 gene leading to complete deficiency of the UGT enzyme.[2] Conversely, CN2 results from a point mutation in the UGT1A1 gene, resulting in reduced production of the UGT enzyme.[2][3]

Epidemiology

Crigler-Najjar syndrome is an exceptionally rare disease, with an incidence rate of 0.6 to 1 in 1 million newborns worldwide.[4][5] Despite its rarity, Crigler-Najjar syndrome requires careful medical attention and specialized care due to the severe consequences associated with elevated bilirubin levels in affected individuals.

Pathophysiology

Bilirubin is one of the byproducts produced when erythrocytes break down. Newborns are particularly vulnerable to hyperbilirubinemia due to their higher hemoglobin concentration at birth and impaired bilirubin excretion processes.

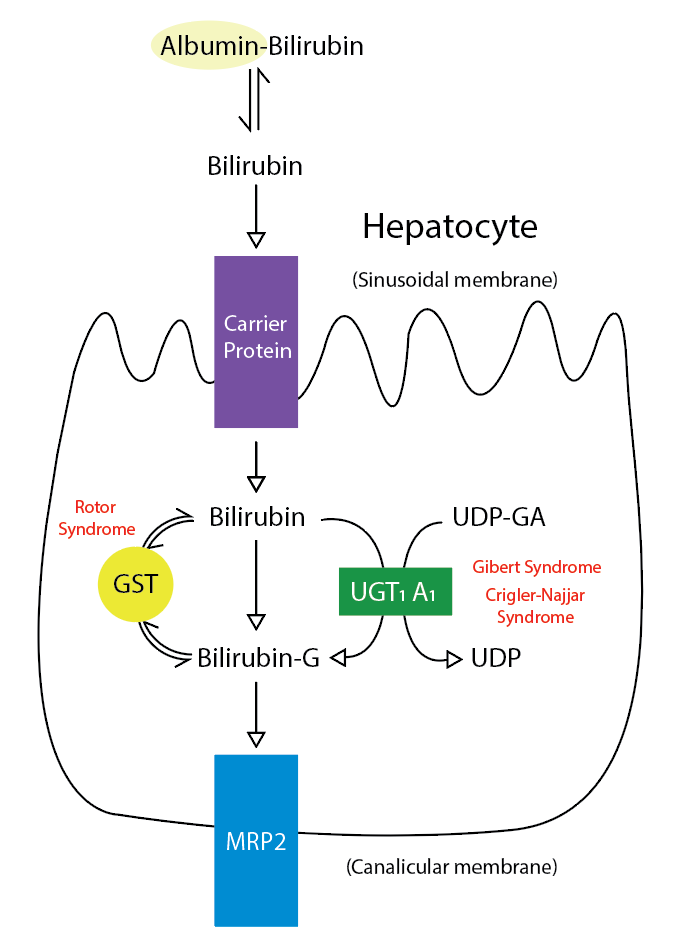

Typically, when erythrocytes break down, bilirubin is in its unconjugated form. This unconjugated bilirubin circulates in the bloodstream and enters hepatocytes, where the UGT enzyme conjugates the bilirubin, making the substance water soluble. Once conjugated, the bilirubin is excreted into bile (see Image. Metabolic Pathway for Bilirubin in the Hepatocyte). In Crigler-Najjar syndrome, a genetic mutation reduces (in CN2) or eliminates (in CN1) this enzyme, leading to decreased or no conjugation and causing an excess of unconjugated bilirubin. Due to the reduced or absent conjugation and excretion, the level of unconjugated bilirubin overwhelms the body's albumin. This surplus of indirect bilirubin accumulates in body tissues such as the skin, sclera, and brain. About 99% of bilirubin is typically bound to albumin, which cannot cross the blood-brain barrier. In contrast, free (unbound) unconjugated bilirubin easily crosses the blood-brain barrier, interacting with neural tissue.[6] This accumulation can lead to severe complications in individuals with Crigler-Najjar syndrome.

Histopathology

Historically, hepatic histology in Crigler-Najjar syndrome was believed to be normal. However, recent studies have revealed certain pathological changes. Microscopically, bile plugs are occasionally observed within canaliculi due to cholestasis. Additionally, Crigler-Najjar syndrome can cause hepatic parenchymal injury. A small study reported transplant patients displaying significant fibrosis seen in the explants, indicating the presence of structural abnormalities in the liver tissue.[7][8]

History and Physical

In CN1, a newborn may exhibit jaundice, although its absence does not rule out the disease. In infants born healthy, persistent jaundice caused by unconjugated bilirubin typically appears within a few days and rapidly worsens by the second week. Factors such as a family history of consanguinity, severe jaundice without signs of hemolysis, relatives or family members undergoing or having undergone exchange transfusion therapy, or a family history of liver diseases support the diagnosis. Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia in CN1 usually ranges from 20 to 25 mg/dL. However, cases with significantly elevated unconjugated bilirubin levels, reaching 50 mg/dL, have been reported.

During physical examination, jaundice is apparent, characterized by yellowish skin and sclera. Stool color remains normal; however, there is reduced excretion of fecal urobilinogen due to markedly decreased bilirubin conjugation. Besides jaundice, there are no abnormal findings in both types, and no signs of liver disease are observed. Older children may exhibit scratch marks on the body due to pruritus. In certain instances, progressive liver dysfunction and additional toxicities can cause hepatosplenomegaly.

Neurological symptoms in Crigler-Najjar syndrome arise from the toxic effects of bilirubin on the basal ganglia and brainstem nuclei for oculomotor and auditory functions. Acute bilirubin encephalopathy (ABE) initially manifests as sleepiness, mild to moderate hypotonia, and a high-pitched cry. Persistence of elevated bilirubin levels leads to the progression of ABE with symptoms such as fever, lethargy, poor suck, irritability, and hypertonia resulting in retrocollis and opisthotonus. Advanced ABE can involve seizures, apnea, and a semi-comatose or comatose state. Respiratory failure or seizures can lead to fatal outcomes. Brainstem auditory-evoked responses (BAER) help detect acute neurological dysfunction.[9]

Chronic bilirubin encephalopathy (CBE), also known as kernicterus, becomes apparent within the first year of life. Choreoathetoid cerebral palsy, sensorineural hearing loss, gaze abnormalities, and enamel hypoplasia characterize CBE. Generally, cognitive function remains unaffected. In instances of CBE, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain reveals alterations in the cerebellum, hippocampus, and brainstem.[10][11]

CN2 is a milder condition characterized by fewer and less severe clinical symptoms. Patients with this syndrome may require periodic assessments to monitor bilirubin levels and liver function, aiding in the management and early detection of potential complications.

Evaluation

Patients suspected of having Crigler-Najjar syndrome should undergo serum unconjugated bilirubin level testing, with significantly higher levels seen in CN1 than CN2. In CN1, the unconjugated bilirubin is between 2 and 25 mg/dL, but severe cases can reach 50 mg/dL. CN2 cases typically exhibit levels below 20 mg/dL.

Historically, collection for bile analysis involved procedures like upper gastrointestinal endoscopy or duodenal catheterization, followed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). However, modern diagnoses primarily rely on genetic testing methods.[12]

The administration of phenobarbital for 2 weeks has decreased serum bilirubin concentration in most patients with CN2.[13] Notably, CN1 does not respond to phenobarbital treatment.

Genetic analysis can be performed on DNA extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes, buccal scrapings, and other tissues, enabling the identification of mutations in the gene encoding the UGT enzyme. Prenatal diagnosis is possible with genetic analysis of chorionic villus samples or amniotic cells aspirated from amniotic fluid aspirates. Additionally, diffusion tensor brain imaging may help detect microstructural gray and white matter changes in CN1 syndrome.[14] Liver biopsy and histopathologic analysis can help to evaluate liver cirrhosis in established cases of hepatosplenomegaly.

Treatment / Management

The primary treatment goal focuses on lowering unconjugated bilirubin levels through phototherapy and plasmapheresis. Although most patients survive beyond puberty without significant brain damage, they are at risk of developing kernicterus later in life. Presently, liver transplantation stands as the sole curative option for CN1.[15]

Phototherapy

The primary treatment approach for CN1 involves intensive, often daily, phototherapy. Phototherapy is often part of the treatment of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia.[16] Intensive phototherapy proves more effective than conventional approaches as it leads to a quicker response, shortens the treatment duration, and minimizes late complications.[17] Phototherapy is less effective in older children and adults due to thicker skin, increased skin pigmentation, and smaller body surface area in proportion to body mass.[15]

Plasmapheresis

Plasmapheresis is the most effective method for removing excess unconjugated bilirubin from the blood during severe hyperbilirubinemia crisis. This process involves extracting blood from the patient, separating blood cells from plasma, and replacing the plasma with donor plasma. The patient's blood is then transfused back after this exchange. Bilirubin tightly binds to albumin; therefore, removing albumin during plasmapheresis effectively reduces bilirubin levels in the bloodstream. Plasmapheresis serves as a targeted approach to eliminating unwanted substances from the blood.

Orlistat

Orlistat, a lipase inhibitor, demonstrates enhanced efficiency when used alongside calcium phosphate. The theory behind its mechanism suggests that it captures unconjugated intestinal bilirubin and aids in its excretion, correlating with the amount of fat expelled in stools.[18](B3)

Calcium Phosphate Supplementation

A randomized controlled study of patients with CN1, who have undergone phototherapy and were supplemented with calcium phosphate, demonstrated an 18% reduction in serum bilirubin levels. This indicates that calcium phosphate may trap photoproducts excreted in the bile.[19] Supporting this, animal studies with rats have shown decreased serum bilirubin concentrations following oral calcium phosphate supplementation, likely due to the trapping of unconjugated bilirubin in the gut.[20](A1)

Liver Transplantation

Liver transplantation stands as the sole therapeutic and definitive treatment method for CN1. The transplanted liver possesses a healthy UGT enzyme, enabling effective bilirubin conjugation and rapidly lowering serum bilirubin levels. Prophylactic liver transplantation is highly recommended to prevent kernicterus, as once this condition develops, it may not be reversible.[21]

Hepatocyte Transplantation

Hepatocyte transplantation is a promising alternative to liver transplantation. During this procedure, healthy hepatocytes are infused into the portal vein or the peritoneal space. This method offers a temporary reduction of serum bilirubin levels, with published reports showing a 50% reduction in bilirubin levels.[22][23](B3)

Gene Therapy

The potential cure for the genetic defect lies in introducing a normal UGT1A1 gene, achieved through ex vivo gene transduction, where the gene is introduced into cultured hepatocytes or vector-mediated gene delivery methods. Adenovirus is the most effective vector for transferring genes to liver cells.[4] Currently, plans for conducting clinical trials in humans are underway, marking significant progress in pursuing a cure.

Inhibition of Bilirubin Production

A single dose of heme oxygenase inhibitors, like tin-protoporphyrin or tin-mesoporphyrin, administered to neonates has demonstrated a 76% decrease in bilirubin levels, eliminating the necessity for phototherapy.[24][25] However, in adults, this effect is short-lived and therefore reserved for acute emergencies.(A1)

Phenobarbitol

Patients with Crigler-Najjar syndrome usually do not require treatment with phenobarbital. However, patients experiencing jaundice that impacts their quality of life may receive phenobarbital therapy, which works by inducing the remaining UGT activity. Notably, phenobarbitol has no role in CN1, but it can reduce the serum bilirubin level by 25% in patients with CN2.[13] There have been documented cases where pregnant women with CN2 were successfully treated with phenobarbital during pregnancy.[26][27](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Distinguishing Crigler-Najjar syndrome from other causes of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia relies on evaluating the bilirubin levels and the duration of hyperbilirubinemia. Additionally, classification is based on underlying causes and specific conditions.

Increased Production

- Hemolysis: Conditions like sickle cell disease, hereditary spherocytosis, and Rh isoimmunization can lead to hemolysis, where the bilirubin level typically remains below 6 to 8 mg/dL in exclusive hemolysis cases in newborns. Rh isoimmunization, incompatible fetal and maternal red cells, can cause pronounced jaundice but is always associated with signs of active hemolysis.

- Ineffective erythropoiesis: Diseases related to ineffective erythropoiesis, such as thalassemia, pernicious anemia, iron deficiency anemia, and lead poisoning, can result in a marked increase in bilirubin levels.

- Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and hematoma: GI bleeding and hematomas contribute to hyperbilirubinemia. One case report with hematochezia and jaundice reported polyp formation was responsible for rectal bleeding related to biliary abnormalities.[28] Conditions like hemobilia, where GI bleeding leads to resorption of blood and an increase in unconjugated bilirubin concentration, can cause jaundice.[29]

Decreased Clearance

- Liver diseases: Any liver disease affecting the conjugation and efficient excretion of bilirubin can lead to jaundice.

- Drug-induced: Liver injury caused by drugs such as amoxicillin, cefazolin, nitrofurantoin, chloramphenicol, and isoniazid can impair the liver's conjugating capacity, resulting in hyperbilirubinemia.[30][31]

Genetic Conditions

- Gilbert syndrome: This common inherited hyperbilirubinemia affects the UGT1A1 gene's promoter region, reducing normal protein production. As the UGT enzyme deficiency is not severe, Gilbert syndrome has benign manifestations, distinguishing it from CN1.

- Lucey-Driscoll syndrome: Also known as transient familial hyperbilirubinemia, it is caused by compounds in the mother's and baby's blood that block the bilirubin breakdown.

- Neonatal jaundice and prematurity: Physiologic jaundice in newborns can result from various factors like liver dysfunction, infection, hypothyroidism, and metabolic disorders. Premature infants often have higher bilirubin levels due to immaturity. Physiologic jaundice usually resolves within the first 10 days of life.

Special Cases

- Breast milk jaundice: Some breastfeeding neonates experience elevated bilirubin within 2 weeks of birth, lasting 3 to 12 weeks, often longer than physiologic jaundice.

- Rotor syndrome and Dubin-Johnson syndrome: Rare inherited disorders causing jaundice with high levels of conjugated bilirubin. Rotor syndrome results from alterations in 2 genes, SLCO1B1 and SLCO1B3, while Dubin-Johnson syndrome results from ABCC2 gene mutations.

Prognosis

CN1 has a poor prognosis, often necessitating emergent intervention during hyperbilirubinemia crises. Once kernicterus develops, this syndrome tends to be irreversible. In contrast, CN2, due to residual UGT enzyme activity, presents with mild symptoms or can even be asymptomatic. Studies report varying incidences of permanent neurological impairment in patients with CN1, ranging up to 30% of cases.[15][32][33]

Complications

An outline of potential complications for Crigler-Najjar syndrome are as follows:

- Kernicterus: Unconjugated bilirubin, being fat-soluble, can penetrate cell membranes. At high serum levels, typically above 25 mg/dL, unconjugated bilirubin can cross the blood-brain barrier, causing neurotoxicity. While more commonly seen in patients with CN1, patients with CN2 are also at risk, especially in cases where serum bilirubin levels may rise to 40 mg/dL. Commonly affected areas of the brain include the hippocampus, geniculate bodies, basal ganglia, and nerve nuclei.[34] Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial to prevent kernicterus.

- Chronic jaundice: Persistent disease and delayed diagnosis lead to chronic jaundice. Bilirubin levels progressively increase due to limited excretion, leading to widespread deposition throughout the body at later stages.

- Cholelithiasis: Increased unconjugated bilirubin concentration can lead to gallstone formation, usually appearing later in life due to the gradual accumulation of bilirubin.

- Liver cirrhosis: Liver cirrhosis develops over a prolonged period. Most children born with Crigler-Najjar syndrome have healthy livers initially. The exact mechanism of liver cirrhosis remains unknown. However, it may result from chronic biliary obstruction secondary to cholelithiasis, toxicity from drugs primarily metabolized in the liver, toxicity from phototherapy, and heme degradation products.[35]

Consultations

Consultations for Crigler-Najjar syndrome typically involve a multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals, including neonatology, pediatric gastroenterology and hepatology, pediatric genetics, genetic counselor, neurologist, and nutritionist or dietitian. The patient's pediatrician or neonatologist is crucial for the initial diagnosis and monitoring of the child's growth and overall health.

Referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist or hepatologist may be necessary for specialized care for liver diseases, including monitoring for liver-related complications. They also play a crucial role in assessing the eligibility for liver transplantation, coordinating the transplant evaluation process, and providing post-transplant care, ensuring comprehensive management of liver-related challenges in Crigler-Najjar syndrome patients.

The care team may also comprise a genetic counselor to help the family understand the genetic implications of the syndrome, provide information about inheritance patterns, and discuss the risk of passing the condition to future generations. If there are neurological complications or concerns, a neurologist may also be necessary. Nutritionists and dietitians can assist in developing specialized diet plans to manage the condtion, ensuring adequate nutrition while minimizing the risk of bilirubin buildup.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Crigler-Najjar syndrome leads to an accumulation of bilirubin in the blood due to an abnormal gene inherited within families. The disease severity varies between its 2 types, making differentiation crucial for appropriate interventions. Screening close relatives is advisable. Tailored patient education, adapted to the parents' understanding, is essential. Detailed information about signs and symptoms empowers parents to facilitate early diagnosis and treatment, preventing complications and enhancing outcomes. Additionally, educating parents about the advantages and disadvantages of different tests and treatments is vital for making well-informed decisions.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A collaborative interprofessional team, utilizing an evidence-based approach for initial diagnosis and subsequent monitoring, is crucial in Crigler-Najjar syndrome. Early diagnosis and timely therapeutic interventions, facilitated by this team, can significantly improve outcomes by reducing the duration of treatments and preventing complications. Neonatologists, drawing on their clinical expertise, play a pivotal role in diagnosing the condition. Pediatric gastroenterologists, medical geneticists, and histopathologists further confirm the diagnosis.

In cases complicated by kernicterus or early ABE, pediatric neurologists are instrumental in managing severity and communicating prognosis details to parents. Pediatric surgeons contribute to curative treatment by liver transplantation. Hospitalized patients' outcomes are influenced by hospital protocols and the quality of care. While patients with CN1 often await liver transplantation, effective management in a hospital setting is essential to prevent kernicterus.[33]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Metabolic Pathway for Bilirubin in the Hepatocyte. Bilirubin-G corresponds to bilirubin glucuronate; the donor is uridine diphosphate glucuronic acid (UDP-GA). This is catalyzed by the enzyme uridine diphosphate-glucuronyltransferase (UGT1A1). Gilbert and Crigler-Najjar syndrome is associated with decreases in UGT1A1 activity. Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) is a carrier protein that assists bilirubin uptake into the cytosol and may be implicated in Rotor syndrome.

Contributed by R Kabir, MD

References

Gailite L, Valenzuela-Palomo A, Sanoguera-Miralles L, Rots D, Kreile M, Velasco EA. UGT1A1 Variants c.864+5G}T and c.996+2_996+5del of a Crigler-Najjar Patient Induce Aberrant Splicing in Minigene Assays. Frontiers in genetics. 2020:11():169. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00169. Epub 2020 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 32211025]

Erps LT, Ritter JK, Hersh JH, Blossom D, Martin NC, Owens IS. Identification of two single base substitutions in the UGT1 gene locus which abolish bilirubin uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase activity in vitro. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1994 Feb:93(2):564-70 [PubMed PMID: 7906695]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKadakol A, Sappal BS, Ghosh SS, Lowenheim M, Chowdhury A, Chowdhury S, Santra A, Arias IM, Chowdhury JR, Chowdhury NR. Interaction of coding region mutations and the Gilbert-type promoter abnormality of the UGT1A1 gene causes moderate degrees of unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia and may lead to neonatal kernicterus. Journal of medical genetics. 2001 Apr:38(4):244-9 [PubMed PMID: 11370628]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCollaud F, Bortolussi G, Guianvarc'h L, Aronson SJ, Bordet T, Veron P, Charles S, Vidal P, Sola MS, Rundwasser S, Dufour DG, Lacoste F, Luc C, Wittenberghe LV, Martin S, Le Bec C, Bosma PJ, Muro AF, Ronzitti G, Hebben M, Mingozzi F. Preclinical Development of an AAV8-hUGT1A1 Vector for the Treatment of Crigler-Najjar Syndrome. Molecular therapy. Methods & clinical development. 2019 Mar 15:12():157-174. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.12.011. Epub 2018 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 30705921]

Ebrahimi A, Rahim F. Crigler-Najjar Syndrome: Current Perspectives and the Application of Clinical Genetics. Endocrine, metabolic & immune disorders drug targets. 2018:18(3):201-211. doi: 10.2174/1871530318666171213153130. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29237388]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStrauss KA, Ahlfors CE, Soltys K, Mazareigos GV, Young M, Bowser LE, Fox MD, Squires JE, McKiernan P, Brigatti KW, Puffenberger EG, Carson VJ, Vreman HJ. Crigler-Najjar Syndrome Type 1: Pathophysiology, Natural History, and Therapeutic Frontier. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 2020 Jun:71(6):1923-1939. doi: 10.1002/hep.30959. Epub 2020 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 31553814]

Mitchell E, Ranganathan S, McKiernan P, Squires RH, Strauss K, Soltys K, Mazariegos G, Squires JE. Hepatic Parenchymal Injury in Crigler-Najjar Type I. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2018 Apr:66(4):588-594. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001843. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29176474]

Fata CR, Gillis LA, Pacheco MC. Liver Fibrosis Associated With Crigler-Najjar Syndrome in a Compound Heterozygote: A Case Report. Pediatric and developmental pathology : the official journal of the Society for Pediatric Pathology and the Paediatric Pathology Society. 2017 Nov-Dec:20(6):522-525. doi: 10.1177/1093526617697059. Epub 2017 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 28590786]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVohr BR, Karp D, O'Dea C, Darrow D, Coll CG, Lester BM, Brown L, Oh W, Cashore W. Behavioral changes correlated with brain-stem auditory evoked responses in term infants with moderate hyperbilirubinemia. The Journal of pediatrics. 1990 Aug:117(2 Pt 1):288-91 [PubMed PMID: 2380830]

Wisnowski JL, Panigrahy A, Painter MJ, Watchko JF. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Abnormalities in Advanced Acute Bilirubin Encephalopathy Highlight Dentato-Thalamo-Cortical Pathways. The Journal of pediatrics. 2016 Jul:174():260-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.03.065. Epub 2016 Apr 22 [PubMed PMID: 27113379]

Wisnowski JL, Panigrahy A, Painter MJ, Watchko JF. Magnetic resonance imaging of bilirubin encephalopathy: current limitations and future promise. Seminars in perinatology. 2014 Nov:38(7):422-8. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2014.08.005. Epub 2014 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 25267277]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTcaciuc E, Podurean M, Tcaciuc A. Management of Crigler-Najjar syndrome. Medicine and pharmacy reports. 2021 Aug:94(Suppl No 1):S64-S67. doi: 10.15386/mpr-2234. Epub 2021 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 34527915]

Arias IM, Gartner LM, Cohen M, Ezzer JB, Levi AJ. Chronic nonhemolytic unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia with glucuronyl transferase deficiency. Clinical, biochemical, pharmacologic and genetic evidence for heterogeneity. The American journal of medicine. 1969 Sep:47(3):395-409 [PubMed PMID: 4897277]

Razek AAKA, Taman SE, El Regal ME, Megahed A, Elzeny S, El Tantawi N. Diffusion Tensor Imaging of Microstructural Changes in the Gray and White Matter in Patients With Crigler-Najjar Syndrome Type I. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 2020 May/Jun:44(3):393-398. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000001008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32217895]

van der Veere CN, Sinaasappel M, McDonagh AF, Rosenthal P, Labrune P, Odièvre M, Fevery J, Otte JB, McClean P, Bürk G, Masakowski V, Sperl W, Mowat AP, Vergani GM, Heller K, Wilson JP, Shepherd R, Jansen PL. Current therapy for Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1: report of a world registry. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 1996 Aug:24(2):311-5 [PubMed PMID: 8690398]

Lund HT, Jacobsen J. Influence of phototherapy on the biliary bilirubin excretion pattern in newborn infants with hyperbilirubinemia. The Journal of pediatrics. 1974 Aug:85(2):262-7 [PubMed PMID: 4842799]

Zhang XR, Zeng CM, Liu J. [Effect and safety of intensive phototherapy in treatment of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia]. Zhongguo dang dai er ke za zhi = Chinese journal of contemporary pediatrics. 2016 Mar:18(3):195-200 [PubMed PMID: 26975813]

Nishioka T, Hafkamp AM, Havinga R, vn Lierop PP, Velvis H, Verkade HJ. Orlistat treatment increases fecal bilirubin excretion and decreases plasma bilirubin concentrations in hyperbilirubinemic Gunn rats. The Journal of pediatrics. 2003 Sep:143(3):327-34 [PubMed PMID: 14517515]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVan der Veere CN, Jansen PL, Sinaasappel M, Van der Meer R, Van der Sijs H, Rammeloo JA, Goyens P, Van Nieuwkerk CM, Oude Elferink RP. Oral calcium phosphate: a new therapy for Crigler-Najjar disease? Gastroenterology. 1997 Feb:112(2):455-62 [PubMed PMID: 9024299]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVan Der Veere CN, Schoemaker B, Bakker C, Van Der Meer R, Jansen PL, Elferink RP. Influence of dietary calcium phosphate on the disposition of bilirubin in rats with unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 1996 Sep:24(3):620-6 [PubMed PMID: 8781334]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSokal EM, Silva ES, Hermans D, Reding R, de Ville de Goyet J, Buts JP, Otte JB. Orthotopic liver transplantation for Crigler-Najjar type I disease in six children. Transplantation. 1995 Nov 27:60(10):1095-8 [PubMed PMID: 7482714]

Ambrosino G, Varotto S, Strom SC, Guariso G, Franchin E, Miotto D, Caenazzo L, Basso S, Carraro P, Valente ML, D'Amico D, Zancan L, D'Antiga L. Isolated hepatocyte transplantation for Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1. Cell transplantation. 2005:14(2-3):151-7 [PubMed PMID: 15881424]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFox IJ, Chowdhury JR, Kaufman SS, Goertzen TC, Chowdhury NR, Warkentin PI, Dorko K, Sauter BV, Strom SC. Treatment of the Crigler-Najjar syndrome type I with hepatocyte transplantation. The New England journal of medicine. 1998 May 14:338(20):1422-6 [PubMed PMID: 9580649]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceValaes T, Petmezaki S, Henschke C, Drummond GS, Kappas A. Control of jaundice in preterm newborns by an inhibitor of bilirubin production: studies with tin-mesoporphyrin. Pediatrics. 1994 Jan:93(1):1-11 [PubMed PMID: 8265301]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKappas A, Drummond GS, Henschke C, Valaes T. Direct comparison of Sn-mesoporphyrin, an inhibitor of bilirubin production, and phototherapy in controlling hyperbilirubinemia in term and near-term newborns. Pediatrics. 1995 Apr:95(4):468-74 [PubMed PMID: 7700742]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHolstein A, Bryan CS. Three consecutive pregnancies in a woman with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type II with good maternal and neonatal outcomes. Digestive and liver disease : official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 2011 Feb:43(2):170. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.08.003. Epub 2010 Sep 16 [PubMed PMID: 20843754]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePassuello V, Puhl AG, Wirth S, Steiner E, Skala C, Koelbl H, Kohlschmidt N. Pregnancy outcome in maternal Crigler-Najjar syndrome type II: a case report and systematic review of the literature. Fetal diagnosis and therapy. 2009:26(3):121-6. doi: 10.1159/000238122. Epub 2009 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 19752526]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHe J, Yu L, Zhang S. Jaundice and rectal bleeding in a young man. Gut. 2011 Jul:60(7):892, 936. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.181149. Epub 2010 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 20542867]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBerry R, Han JY, Kardashian AA, LaRusso NF, Tabibian JH. Hemobilia: Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment(☆). Liver research. 2018 Dec:2(4):200-208. doi: 10.1016/j.livres.2018.09.007. Epub 2018 Sep 22 [PubMed PMID: 31308984]

deLemos AS, Ghabril M, Rockey DC, Gu J, Barnhart HX, Fontana RJ, Kleiner DE, Bonkovsky HL, Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN). Amoxicillin-Clavulanate-Induced Liver Injury. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2016 Aug:61(8):2406-2416. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4121-6. Epub 2016 Mar 22 [PubMed PMID: 27003146]

Björnsson ES. Drug-induced liver injury due to antibiotics. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2017 Jun-Jul:52(6-7):617-623. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2017.1291719. Epub 2017 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 28276834]

Suresh G, Lucey JF. Lack of deafness in Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1: a patient survey. Pediatrics. 1997 Nov:100(5):E9 [PubMed PMID: 9347003]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStrauss KA, Robinson DL, Vreman HJ, Puffenberger EG, Hart G, Morton DH. Management of hyperbilirubinemia and prevention of kernicterus in 20 patients with Crigler-Najjar disease. European journal of pediatrics. 2006 May:165(5):306-19 [PubMed PMID: 16435131]

Hamza A. Kernicterus. Autopsy & case reports. 2019 Jan-Mar:9(1):e2018057. doi: 10.4322/acr.2018.057. Epub 2019 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 30863731]

Barış Z, Özçay F, Usta Y, Özgün G. Liver Cirrhosis in a Patient with Crigler Najjar Syndrome. Fetal and pediatric pathology. 2018 Aug:37(4):301-306. doi: 10.1080/15513815.2018.1492053. Epub 2018 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 30260719]