Introduction

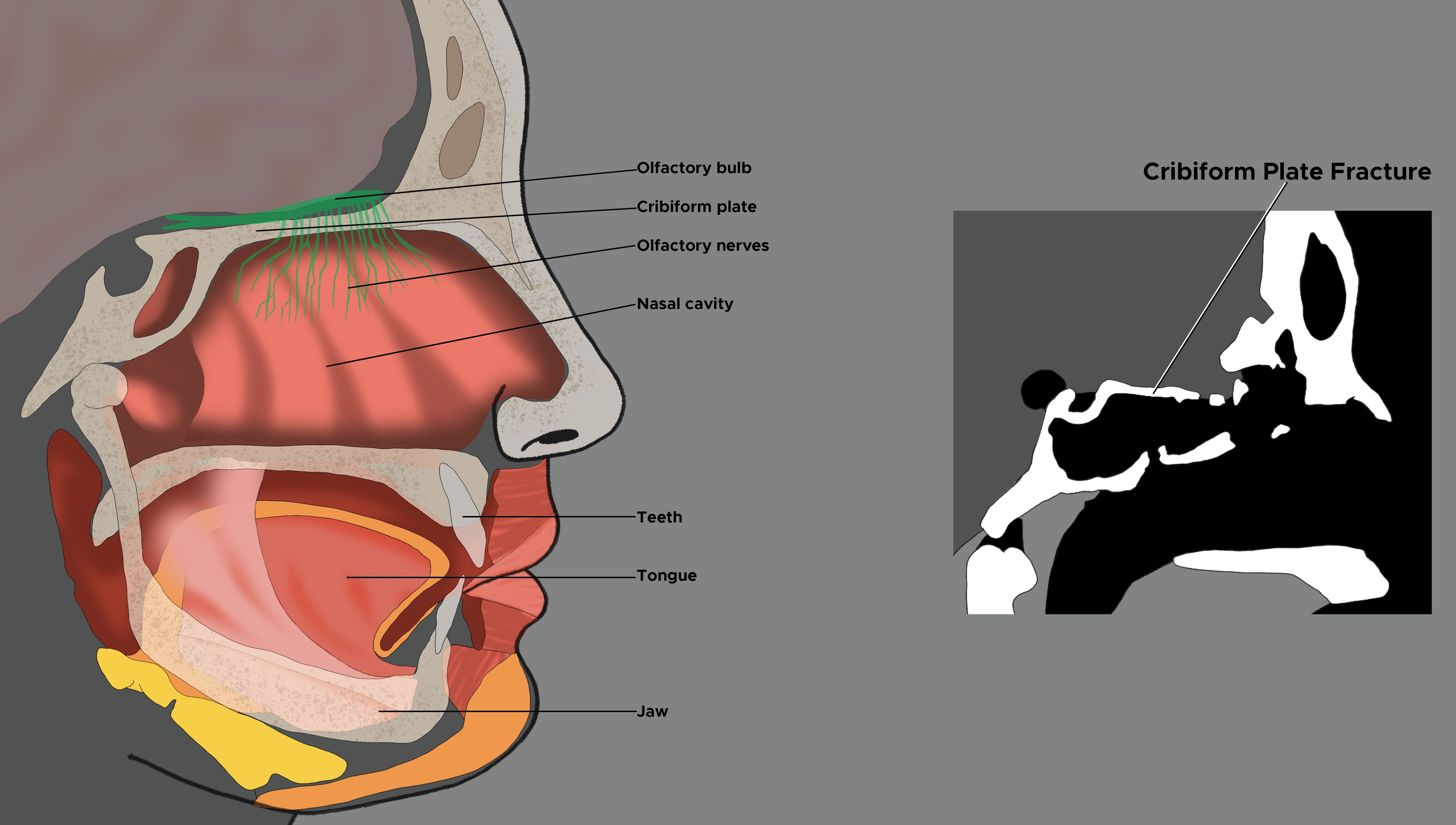

The cribriform plate is a portion of the ethmoid bone located at the base of the skull. The base of the skull is the term used to describe the most inferior portion of the skull. It is comprised of portions of the frontal bone, ethmoid bone, sphenoid bone, temporal bone, and occipital bone. The base of the skull is divided into three sections: the anterior fossa, the middle fossa, and the posterior fossa. Within the center of the anterior fossa sits the ethmoid bone. This bone is located in the midline and extends from the medial wall of the orbits over the nasal septum, and comprises the roof of the nasal cavity.

This narrow bony structure contains deep grooves known as olfactory fossa, which support the olfactory bulbs. It is perforated by numerous small openings, known as olfactory foramina, through which the olfactory nerve fibers enter into the roof of the nasal cavity to allow olfaction.

The cribriform plate is the thinnest portion of the base of the skull and is, therefore, susceptible to fracture in cases of facial trauma.[1] Fractures can lead to partial or complete anosmia secondary to a severing of the olfactory nerves or due to contusion of the olfactory bulb itself.[1] The dura overlying the cribriform plate is thin and tightly adherent to the skull; thus, fractures of the cribriform plate can easily tear the dura and lead to leakage of cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) into the nasal cavity. Once the dura is compromised, the patient is at risk for complications such as pneumocephalus, encephalocele, and ascending infections leading to meningitis.[1]

Prompt evaluation and diagnosis can facilitate early treatment and reduce the risk of developing these potentially life-threatening complications. Diagnosis of cribriform plate fractures and dural fistulas can be difficult; thus, clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating a patient with facial trauma to allow early diagnosis and prevention of serious complications.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The most common cause of cribriform plate fractures is blunt force trauma to the face, which makes up 80%-90% of cases.[1] A fracture of the cribriform plate requires a heavy frontal impact and a significant mechanism of injury. This fracture rarely occurs in isolation and is generally associated with other facial bone fractures. As such, data on specific causes of cribriform plate fracture alone is lacking. Overall, the most common cause of midface fracture in adults is traffic accidents, which comprise nearly two-thirds of cases.[2] The next most common cause is assault at 21%, followed by falls at 9%.[2] Occupational injuries and sports-related injuries make up a smaller percentage.

In young children, fractures of the midface are more commonly due to falls. In children aged 11 to 14 years, sports-related injuries predominate, and by age 15 to 18, assault becomes most common. The remaining causes of cribriform plate fractures include penetrating trauma, such as gunshot wounds, and iatrogenic complications. Unlike in cases of blunt trauma, cribriform plate fractures do occur in isolation as a complication of endoscopic sinus surgery. The rate of CSF leak secondary to the iatrogenic complication is reported to be less than 1%.[3]

Epidemiology

Naso-ethmoid fractures comprise about 5%-15% of facial fractures.[1] Midface fractures are more frequently seen in males than females, at a rate of 3 to 1. The peak incidence is seen in ages 21 to 30 years.[2] Cultural and socioeconomic differences influence these rates.[2]

Traffic accidents are the most common cause of cribriform plate fractures overall, and motorcycle accidents pose a particularly high risk.[2] Alcohol consumption is strongly associated with midface fractures. A study of 200 patients with midface fractures found 33% were under the influence of alcohol at the time of their injury.[2]

History and Physical

A patient presenting with significant trauma to the face requires extensive evaluation and should be managed in accordance with the Advanced Trauma Life Support guidelines.[4] A primary survey must be completed immediately to assess and treat life-threatening injuries. The survey consists of assessing the patency of the airway, breathing, and circulation with hemorrhage control. Appropriate cervical spinal precautions should be implemented. Facial fractures can lead to altered facial anatomy, airway compromise, and aspiration risk. Clinicians should have a low threshold for intubation if current or impending airway compromise is suspected.[5] A rapid neurologic assessment should be completed, and all patients with a Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score of 8 or below require emergent intubation.

After addressing acute life threats, a secondary head-to-toe trauma evaluation should be completed. The head should be examined for scalp hematomas, lacerations, and depressed skull fractures. Assess for signs of a basilar skull fracture, including peri-orbital ecchymosis, known as "raccoon eyes," and retro-auricular ecchymosis, also known as "Battle sign" and hemotympanum.[4] Clear or bloody fluid draining from the nose or ear is concerning for a basilar skull fracture with a CSF leak. Specifically, clear rhinorrhea is highly suspicious for a cribriform plate fracture with a dural fistula.

Attempt to obtain all available history from the patient, medics, family, and bystanders. Determine the mechanism of injury and the patient's past medical history. In cases of a motor vehicle collision, determine seat belt use, airbag deployment, steering wheel deformity, and condition of the vehicle. Perform a review of systems in patients that are responsive. Headache, nausea, vomiting, and alterations in consciousness are concerning for acute intracranial injury.

Stable patients with a cribriform plate fracture will likely present with post-traumatic midface pain and epistaxis. All such patients require thorough exams of the head, neck, face, ears, nose, and throat. If the epistaxis resolves but clear rhinorrhea persists, this is highly concerning for a post-traumatic CSF leak.

Evaluation

The preferred imaging modality for the diagnosis of cribriform plate fractures is head and maxillofacial computed tomography (CT). Ideally, this will be high resolution with 1 mm cuts, including sagittal, coronal, and axial views that should be performed.[6]

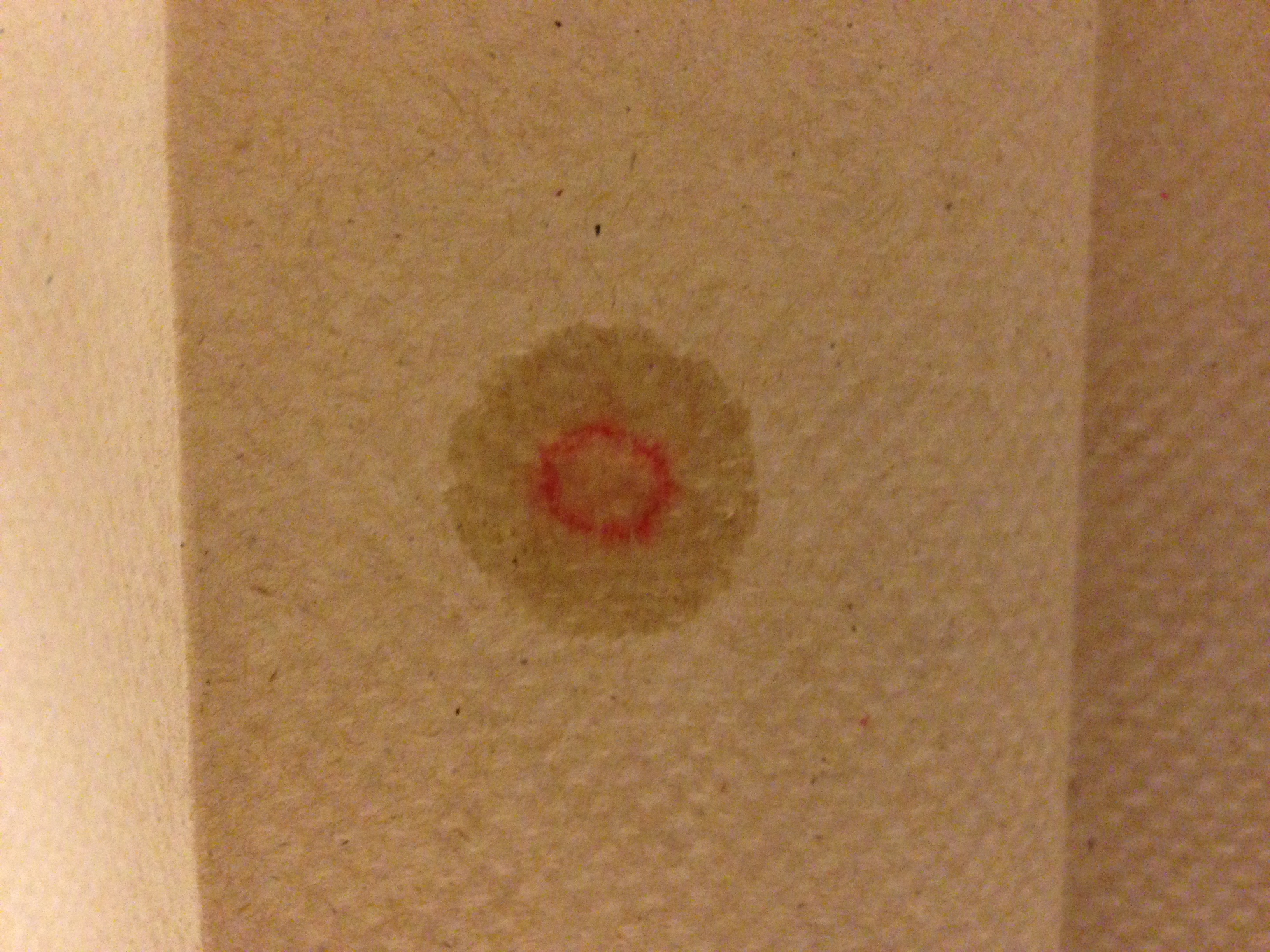

The filter test has been used to aid in identifying CSF in bloody secretions. When placed on the filter paper, CSF moves outward while blood moves inward, showing a "double halo" sign. This test, while quick and easy to perform, has not been shown to be significantly sensitive nor specific in detecting CSF; thus, further diagnostic studies are warranted. If present, nasal and/or otic secretions samples should be obtained and evaluated for beta trace protein and beta-2-transferrin. Beta trace protein is found in high concentrations in CSF. Beta-2-transferrin is found in CSF, aqueous humor, and perilymph. Positive tests of these two substances are highly indicative of a CSF leak.[7][8][9]

Treatment / Management

All basilar skull fractures warrant admission for observation and potential surgical treatment. The level of consciousness and additional intracranial injury play a large factor in the treatment of cribriform plate fracture. Conservative treatment tends to be chosen for those who initially present with a GCS >8. Most traumatic CSF leaks resolve spontaneously within the first seven days, and a lumbar drain may be employed to decrease intracranial pressure and facilitate spontaneous resolution[10]. A small percentage of post-traumatic CSF leaks may persist for several months. Surgical closure is more likely to be the chosen treatment for patients who initially present with a GCS of <8 or have a persistent leak for greater than 7 days. Leaks persistent for more than 7 days have an increased risk for the development of bacterial meningitis.[11][12] (B2)

An endoscopic repair has been shown to be highly effective, with a resolution rate of greater than 95%, and requires no additional treatment. If fractures are in the extreme anterior cribriform, sufficient access may not be possible endoscopically, and an open surgical approach may be required. If an open approach is used, minimizing retraction of the frontal lobes is important to optimize the olfactory function and decrease the chance of postoperative frontal lobe syndrome[13]. An anterior subcranial approach can be employed to minimize frontal lobe retraction in many cases. However, a formal anterior craniotomy may be required in rare instances.[14] Prophylactic antibiotic use is not currently supported for cribriform plate fractures due to a lack of research, though patients with an active CSF leak will be treated with antibiotics in many centers.[15](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Given the severe mechanism of injury involved with cribriform plate fracture, these patients should be evaluated for concomitant traumatic brain injuries (TBI), intracranial hemorrhage, and other facial fractures.

Treatment Planning

Initial, conservative treatment involves bed rest and avoidance of Valsalva or other maneuvers that can increase intracranial pressure. Acetazolamide can be used to decrease CSF pressure, and a lumbar drain can be placed to measure opening pressures and maintain a lower intracranial pressure and facilitate spontaneous resolution of the leak.[16]

If the leak persists for more than 1 week, surgical repair can be entertained. High-resolution CT scans with 1 mm cuts are the preferred imaging modality to plan repair and image-guidance protocols can be used to facilitate intraoperative navigation. This imaging can also identify post-traumatic encephalocele that will need management also. All but most anterior cribriform fracture-related leaks can be managed endoscopically, and fascial or bone grafts, vascularized mucosal flaps, or allogenic materials have all been used successfully in repairs. It is important to confidently identify the leak site intraoperatively, and this typically requires a total ethmoidectomy and possible sphenoidotomy. If the leak can still not be identified, an intraoperative intrathecal fluorescein injection can help locate it. [17]

Prognosis

The prognosis of a cribriform plate fracture is variable and highly dependent upon initial presentation and concomitant injuries. For those patients who initially present with a GCS of greater than 8 and do not require surgical intervention, the prognosis is good, and CSF leaks generally resolve spontaneously. The prognosis of cribriform plate fracture alone is good, and complications, morbidity, and mortality are most often tied to concomitant injuries rather than due to the cribriform plate fracture itself.[18]

Complications

Anosmia, or a loss of smell, is a common complication of cribriform plate fracture. The injury is due to the damage of olfactory nerves or injury to the olfactory bulb itself. Anosmia can be partial or complete. If neurosurgical repair is indicated, an approach done without lifting the frontal lobes has been shown to decrease the risk of detaching olfactory elements and subsequent anosmia.[19]

Patients with a history of cribriform plate fractures have an increased risk of ascending infections and bacterial meningitis. The probability of developing meningitis is higher with a documented CSF leak. Higher rates of meningitis were noted, with fractures occurring more than one year ago. [20]

One study showed the majority of meningitis cases post cribriform plate fractures in the pediatric population were caused by S. pneumoniae and recommended the pneumococcal vaccination for those who displayed CSF leak.[21]

Cribriform plate fracture with persistent CSF leak can lead to a headache syndrome. The headaches are exacerbated by being upright and resolve when supine. This syndrome is similar to post-dural puncture headache, and the etiology (decreased intracranial pressure) is the same.

Clinicians must evaluate for nasal septal hematoma in patients with cribriform plate fractures and midface trauma. An undiagnosed nasal septal hematoma can result in avascular necrosis of the septal cartilage and subsequent saddle nose deformity.[22]

Nasotracheal intubation and nasogastric tube placement are contraindicated in patients with midface trauma due to the possibility of tubes being passed into the cranial vault via a fractured cribriform plate.

Consultations

Treating a cribriform plate fracture takes an interprofessional team approach. In the emergency department, prompt neurosurgical evaluation is indicated for all basilar skull fractures. Proper management of cribriform plate fractures and associated head and facial injuries may require the collaboration of multiple specialists, including neurosurgery and otolaryngology.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Methods to prevent cribriform plate fractures center around precautions to reduce the risk of high-impact facial injuries. Head protection and face masks during high-impact sports should be strongly encouraged. Educating parents about the importance of seat belts and age-appropriate car seats can reduce instances of facial trauma in motor vehicle collisions. Improving safety measures that place small children at risk for falls can be beneficial. Community resources to curb violence and prevent assault could also help lower the incidence of cribriform plate fracture.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Cribriform plate fracture arises as a complication of facial trauma. Fractures can be missed on CT, and CSF rhinorrhea may be difficult to distinguish from epistaxis or mucus secretions immediately post-injury.

Morbidity associated with meningitis and continuous loss of CSF is high. Cribriform plate fractures and associated dural fistulas can be missed. Proper imaging and laboratory studies are critical in the diagnosis. Endoscopic repair of a cribriform plate fracture has shown to be highly effective, with the repair being successful 97% of the time and postoperative adjunct medication being needed only 12% of the time for symptomatic idiopathic intracranial hypertension.[14]

While otolaryngology is almost always involved in the care of patients with cribriform plate fractures, it is important to involve an interprofessional team of specialists, such as neurosurgery, for the care of complicated or persistent leaks lasting more than 7 days. Nurses are a vital part of the interprofessional group as they monitor routine rounding and can identify and quantify persistent rhinorrhea due to leakage of CSF. In the event a patient with a cribriform plate fracture does require surgery, the pharmacist will ensure patients are on proper analgesics and antibiotics if necessary.[8]

The outcomes of cribriform plate fracture depend on consciousness at presentation and any additional intracranial injury. Prompt consultation with an interprofessional group of specialists is recommended to improve outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kühnel TS, Reichert TE. Trauma of the midface. GMS current topics in otorhinolaryngology, head and neck surgery. 2015:14():Doc06. doi: 10.3205/cto000121. Epub 2015 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 26770280]

Septa D, Newaskar VP, Agrawal D, Tibra S. Etiology, incidence and patterns of mid-face fractures and associated ocular injuries. Journal of maxillofacial and oral surgery. 2014 Jun:13(2):115-9. doi: 10.1007/s12663-012-0452-9. Epub 2012 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 24822001]

Gray ST, Wu AW. Pathophysiology of iatrogenic and traumatic skull base injury. Advances in oto-rhino-laryngology. 2013:74():12-23. doi: 10.1159/000342264. Epub 2012 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 23257548]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKirkpatrick AW, Ball CG, D'Amours SK, Zygun D. Acute resuscitation of the unstable adult trauma patient: bedside diagnosis and therapy. Canadian journal of surgery. Journal canadien de chirurgie. 2008 Feb:51(1):57-69 [PubMed PMID: 18248707]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceColbenson K. An Algorithmic Approach to Triaging Facial Trauma on the Sidelines. Clinics in sports medicine. 2017 Apr:36(2):279-285. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2016.11.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28314417]

Truong TA. Initial Assessment and Evaluation of Traumatic Facial Injuries. Seminars in plastic surgery. 2017 May:31(2):69-72. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1601370. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28496385]

Pretto Flores L,De Almeida CS,Casulari LA, Positive predictive values of selected clinical signs associated with skull base fractures. Journal of neurosurgical sciences. 2000 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 11105835]

Oh JW, Kim SH, Whang K. Traumatic Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak: Diagnosis and Management. Korean journal of neurotrauma. 2017 Oct:13(2):63-67. doi: 10.13004/kjnt.2017.13.2.63. Epub 2017 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 29201836]

Chan DT, Poon WS, IP CP, Chiu PW, goh KY. How useful is glucose detection in diagnosing cerebrospinal fluid leak? The rational use of CT and Beta-2 transferrin assay in detection of cerebrospinal fluid fistula. Asian journal of surgery. 2004 Jan:27(1):39-42 [PubMed PMID: 14719513]

Daly DT, Lydiatt WM, Ogren FP, Moore GF. Extracranial approaches to the repair of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 1992 Jul:71(7):311-3 [PubMed PMID: 1505379]

Yilmazlar S,Arslan E,Kocaeli H,Dogan S,Aksoy K,Korfali E,Doygun M, Cerebrospinal fluid leakage complicating skull base fractures: analysis of 81 cases. Neurosurgical review. 2006 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 15937689]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrodie HA, Thompson TC. Management of complications from 820 temporal bone fractures. The American journal of otology. 1997 Mar:18(2):188-97 [PubMed PMID: 9093676]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceArcher JB, Sun H, Bonney PA, Zhao YD, Hiebert JC, Sanclement JA, Little AS, Sughrue ME, Theodore N, James J, Safavi-Abbasi S. Extensive traumatic anterior skull base fractures with cerebrospinal fluid leak: classification and repair techniques using combined vascularized tissue flaps. Journal of neurosurgery. 2016 Mar:124(3):647-56. doi: 10.3171/2015.4.JNS1528. Epub 2015 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 26473788]

Sanghvi S, Sarna B, Alam E, Pasol J, Levine C, Casiano RR. Role of Adjunct Treatments for Idiopathic CSF Leaks After Endoscopic Repair. The Laryngoscope. 2021 Jan:131(1):41-47. doi: 10.1002/lary.28720. Epub 2020 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 32401375]

Ratilal BO,Costa J,Pappamikail L,Sampaio C, Antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing meningitis in patients with basilar skull fractures. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2015 Apr 28; [PubMed PMID: 25918919]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAbdelFatah MAR. Acetazolamide, Short Bed Rest, and Subfascial Off-Suction Drainage in Preventing Persistent Spinal Fluid Leaks from Incidental Dural Tears. Journal of neurological surgery. Part A, Central European neurosurgery. 2023 Jan 24:():. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1760228. Epub 2023 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 36693410]

Vedhapoodi AG, Periyasamy A, Senthilkumar D. A Novel Combined Transorbital Transnasal Endoscopic Approach for Reconstruction of Posttraumatic Complex Anterior Cranial Fossa Defect. Asian journal of neurosurgery. 2021 Jan-Mar:16(1):136-140. doi: 10.4103/ajns.AJNS_363_20. Epub 2021 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 34211881]

Altundag A, Saatci O, Kandemirli SG, Sanli DET, Duz OA, Sanli AN, Yildirim D. Imaging Features to Predict Response to Olfactory Training in Post-Traumatic Olfactory Dysfunction. The Laryngoscope. 2021 Jul:131(7):E2243-E2250. doi: 10.1002/lary.29392. Epub 2021 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 33449371]

Rombaux P, Mouraux A, Bertrand B, Nicolas G, Duprez T, Hummel T. Retronasal and orthonasal olfactory function in relation to olfactory bulb volume in patients with posttraumatic loss of smell. The Laryngoscope. 2006 Jun:116(6):901-5 [PubMed PMID: 16735894]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKamochi H, Kusaka G, Ishikawa M, Ishikawa S, Tanaka Y. Late onset cerebrospinal fluid leakage associated with past head injury. Neurologia medico-chirurgica. 2013:53(4):217-20 [PubMed PMID: 23615410]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSantos SF, Rodrigues F, Dias A, Costa JA, Correia A, Oliveira G. [Post-traumatic meningitis in children: eleven years' analysis]. Acta medica portuguesa. 2011 May-Jun:24(3):391-8 [PubMed PMID: 22015025]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGinsburg CM. Nasal septal hematoma. Pediatrics in review. 1998 Apr:19(4):142-3 [PubMed PMID: 9557069]