Introduction

The muscles of the pharynx play an integral role in many vital processes such as breathing, swallowing, prevention of aspiration, and speaking. Coordination of the pharyngeal musculature with the laryngeal and tongue muscles is essential to the efficiency of these essential human functions. Broadly categorized by their orientation (circular versus longitudinal), these muscles allow the pharynx to change its size and shape to achieve with the required function. Understanding the embryology, structure, blood supply, lymphatics, innervation, and function of each of the paired pharyngeal muscles is critical for the diagnosis and treatment of many pathologic conditions.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

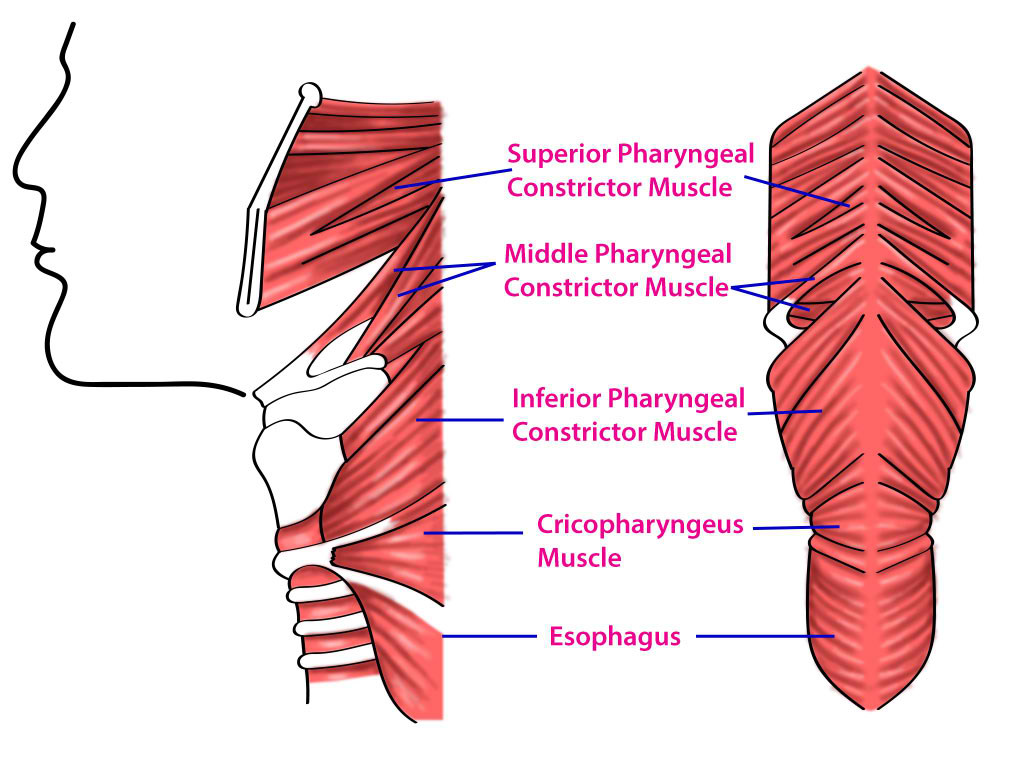

The limits of the pharynx extend from the base of the skull superiorly to the cricoid cartilage inferiorly. The three pharyngeal constrictor muscles are delineated by their position relative to one another (superior, middle, and inferior). Their different attachment points and sequential, involuntary contraction allow the pharyngeal lumen to be closed in a cranial to a caudal direction for peristalsis during swallowing, while alternately remaining open for breathing and speaking.[2]

The longitudinal muscles, palatopharyngeus (PP), stylopharyngeus (STP), and salpingopharyngeus (SLP), merge caudally to become the medial aspect of the lateral wall of the pharynx. They function to shorten and elevate the pharynx during deglutition. There is a hypothesis that because of their insertion relative to the piriform recess, their contraction may also assist in the clearance of food residue from the pyriform. Caudal to the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles, the cricopharyngeus muscle functions as part of the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) and has a close relationship with the three longitudinal muscle pairs.[2][3]

Embryology

Embryologically these muscles are derived from the branchial arches that form during the fourth through seventh weeks of gestation. Their blood supply and innervation correlate with the arch from which they derive. The STP is derived from the third branchial arch, while the rest of the pharyngeal muscles arise from the fourth pharyngeal arch.[4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The pharyngeal muscles receive their blood supply from branches of the external carotid artery according to their anatomic location. The ascending pharyngeal artery commonly supplies all of the pharyngeal muscles. Additionally, the constrictor muscles receive vascular supply from the tonsillar branch of the facial artery and the muscular branch of the inferior thyroid artery. The PP and SLP muscles receive additional blood supply from the ascending palatine branch of the facial artery, and the descending palatine branch of the maxillary artery.[5][6][7]

The lymphatic drainage of the pharynx is a complex network that has a preferential path for specific anatomic locations. In general, the nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal region lymphatics drain via the middle posterior cervical nodes to the supraclavicular node group.[8]

Nerves

The pharyngeal plexus provides the sensory and motor innervation to the pharynx. This innervation forms via contributions from the vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves, as well as branches of the superior cervical ganglion. Specifically, the motor innervation of the STP muscle is mostly from the glossopharyngeal nerve, while the vagus nerve supplies the innervation to the other pharyngeal muscles. The pharyngeal muscles have a high nerve-muscle fiber ratio of 1:2 to 1:6 which allows for precisely coordinated pharyngeal functions.[2] The innervation of the cricopharyngeus muscle is from the pharyngeal plexus and the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

Muscles

The superior constrictor pharyngeal muscle (SCPM) originates at the lateral base of tongue, medial pterygoid plate, pterygomandibular raphe, pterygoid hamulus, and the posterior end of the mylohyoid line. It inserts onto the pharyngeal raphe and contracts during deglutition to move the soft palate to the posterior pharyngeal wall, thus preventing the bolus from moving upward into the naopharynx.[2][9]

The middle constrictor pharyngeal muscle (MCPM) originates from the stylohyoid ligament and the greater and lesser horns of the hyoid bone. It fans out to attach along the pharyngeal raphe, but this muscle rarely reaches the top of the pharynx (superiorly) or thyroid cartilage (inferiorly). The contraction of these fibers constrict and close the pharynx during deglutition to propel the bolus downward.[1]

The inferior constrictor pharyngeal muscle (ICPM) originates from the cricoid and thyroid cartilages and crosses the cricothyroid muscle. It inserts onto the pharyngeal raphe and constricts sequentially in coordination with the SCPM and MCPM during deglutition to propel the bolus towards the esophagus. Due to the finding that some of the inferior ICPM fibers merge with fibers of the cricothyroid muscle, the belief is that the ICPM serves as part of the functional UES.[10][11]

The cricopharyngeus muscle attaches to the cricoid cartilage and wraps circumferentially around the pharynx. In contrast to the constrictor muscles, it maintains a contracted state during resting physiology to maintain the UES and thus helps to prevent pharyngeal reflux of esophageal and gastric contents. During deglutition, the cricopharyngeus relaxes as the bolus descends through the pharynx to allow passage into the esophagus. The coordination of the constrictor muscle peristalsis with this opening of the UES also creates a negative pressure to propel the bolus further in the inferior direction.[2][12] Failure of the cricopharyngeus muscle to relax at the proper time can lead to dysphagia, aspiration, and the formation of a pathologic outpouching of the pharynx called Zenker's diverticulum (see below).

The PP originates from both the oral and nasal side of the soft palate and inserts along the pharyngeal wall. It functions to elevate the pharynx and moves the lateral pharyngeal wall toward the midline, which propels a bolus downward during deglutition.[13] The STP muscle originates from the styloid process and inserts along the pharyngeal wall. It functions along with the PP and SLP to elevate the pharynx during deglutition.The SLP originates from the Eustachian tube and inserts along the pharyngeal wall. It functions along with the PP and STP to elevate the pharynx during deglutition.[3]

Physiologic Variants

Minor anatomic and physiologic variations can occur in these pharyngeal muscles, due to the proximity to other structures and a rich neurovascular supply. Additional attachments by the longitudinal muscle group is a common occurrence, with insertions into the palatine tonsil, epiglottis, arytenoid and thyroid cartilage, among other areas. In one study, the SLP muscle was found to be present in only 63% of cadavers, with the majority being very thin.[3][14]

Surgical Considerations

The pharyngeal muscles have many important implications regarding potential dysphagia, aspiration, and breathing problems following trauma, neurological diseases, muscular diseases, and surgical resection for benign and malignant processes. Patients undergoing significant resection of pharyngeal muscles during oncologic surgery, or those with neurological or muscular diseases should have an assessment for dysphagia and aspiration. Feeding tubes, dietary modifications, and swallowing therapy may be required. Another example is the importance of preservation of the STP muscle during lateral pharyngoplasty for obstructive sleep apnea.[15]

Clinical Significance

Swallowing requires precise coordination between many different nerves and muscles, and many problems can arise. As noted above, a common important clinical problem is dysphagia. The prevalence of dysphagia is around 50% in the very elderly and is also 50% in those with neurologic dysfunction. Many severe complications can arise from dysphagia, such as malnutrition or pulmonary aspiration of food or saliva. The prevalence of dysphagia makes it a highly prioritized area of research.[16][17][18]

The pharyngeal muscles also can be implicated in other processes such as sleep apnea. During sleep, these pharyngeal muscles may become hypotonic and are unable to prevent the collapse of the airway if increased airway resistance and/or narrowing are present from factors such as generalized hypotonia, obesity, macroglossia (large tongue), lingual tonsil hypertrophy, base of tongue masses, tonsillar hypertrophy, retrognathia (short jaw), pharyngeal masses, etc.).[19]

Other Issues

Failure of relaxation of the cricopharyngeus muscle during swallowing (cricopharyngeal achalasia) can lead to both dysphagia and a pathologic outpouching of the pharynx called Zenker's diverticulum. Since the cricopharyngeus does not relax in the usual fashion, pressure from the constrictor muscles and the bolus builds up in the pharynx causing an outpouching of the pharynx that fills with food. There may be a mass in the neck that changes size and is associated with gurgling sounds as it fills and empties. Cricopharyngeal achalasia may occur as a primary process or secondary to injury to the nerve supply or muscle from benign or malignant processes. Since the cricopharyngeus is innervated by the pharyngeal plexus and the recurrent laryngeal nerve, a thorough workup including complete head, neck, and chest exams are indicated. If possible malignancy is suspected, esophagoscopy, laryngoscopy, and bronchoscopy are required. MRI or CT of the neck and chest may also be necessary since the vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerves pass through both the neck and chest.

A recent review of cricopharyngeal achalasia etiologies included idiopathic (28%), cerebrovascular accident (28%), neurologic disease (17%), head and neck radiation treatment (11%), Zenker's diverticulum (10%), and myositis (5%). The most commonly employed treatments were cricopharyngeus muscle botulinum toxin injection (40%), endoscopic cricopharyngeal myotomy (30%), dilation (25%), and open cricopharyngeal myotomy (15%). The authors concluded that there is a need for prospective studies to compare the outcomes of the existing treatments because the existing studies are limited by small sample sizes, heterogeneity of etiologies, and treatments of cricopharyngeal achalasia, as well as short-duration follow-up. This limited assessment of the superiority of one treatment over another.[20]

Several endoscopic and surgical treatments have been developed to treat cricopharyngeal achalasia and Zenker's diverticulum. In one study of recurrent Zenker's diverticula, 56 patients met inclusion criteria. Primary surgery was open in 30.3% and endoscopic in 69.6%. Revision surgery was performed via an open surgical approach in 37.5% of cases and with an endoscopic approach in 62.5% of cases. The revision technique was based on diverticulum size, age of patients, comorbidities, and preferences of patients and surgeons. There were no major complications and few minor ones. The authors concluded that Zenker's diverticulum symptoms can recur regardless of the primary treatment modality. Both endoscopic and open approaches can safely treat recurrent Zenker's diverticula.[21]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Sakamoto Y. Gross anatomical observations of attachments of the middle pharyngeal constrictor. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2014 May:27(4):603-9. doi: 10.1002/ca.22344. Epub 2013 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 24343865]

Shaw SM, Martino R. The normal swallow: muscular and neurophysiological control. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2013 Dec:46(6):937-56. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2013.09.006. Epub 2013 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 24262952]

Choi DY, Bae JH, Youn KH, Kim HJ, Hu KS. Anatomical considerations of the longitudinal pharyngeal muscles in relation to their function on the internal surface of pharynx. Dysphagia. 2014 Dec:29(6):722-30. doi: 10.1007/s00455-014-9568-z. Epub 2014 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 25142243]

Adams A, Mankad K, Offiah C, Childs L. Branchial cleft anomalies: a pictorial review of embryological development and spectrum of imaging findings. Insights into imaging. 2016 Feb:7(1):69-76. doi: 10.1007/s13244-015-0454-5. Epub 2015 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 26661849]

Huang MH, Lee ST, Rajendran K. Clinical implications of the velopharyngeal blood supply: a fresh cadaveric study. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1998 Sep:102(3):655-67 [PubMed PMID: 9727428]

Hacein-Bey L, Daniels DL, Ulmer JL, Mark LP, Smith MM, Strottmann JM, Brown D, Meyer GA, Wackym PA. The ascending pharyngeal artery: branches, anastomoses, and clinical significance. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2002 Aug:23(7):1246-56 [PubMed PMID: 12169487]

Devadas D, Pillay M, Sukumaran TT. A cadaveric study on variations in branching pattern of external carotid artery. Anatomy & cell biology. 2018 Dec:51(4):225-231. doi: 10.5115/acb.2018.51.4.225. Epub 2018 Dec 29 [PubMed PMID: 30637155]

Lengelé B, Hamoir M, Scalliet P, Grégoire V. Anatomical bases for the radiological delineation of lymph node areas. Major collecting trunks, head and neck. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2007 Oct:85(1):146-55 [PubMed PMID: 17383038]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTsumori N, Abe S, Agematsu H, Hashimoto M, Ide Y. Morphologic characteristics of the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle in relation to the function during swallowing. Dysphagia. 2007 Apr:22(2):122-9 [PubMed PMID: 17318687]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMu L, Sanders I. Neuromuscular compartments and fiber-type regionalization in the human inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle. The Anatomical record. 2001 Dec 1:264(4):367-77 [PubMed PMID: 11745092]

Sakamoto Y. Interrelationships between the innervations from the laryngeal nerves and the pharyngeal plexus to the inferior pharyngeal constrictor. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2013 Oct:35(8):721-8. doi: 10.1007/s00276-013-1102-8. Epub 2013 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 23515953]

Uludag M, Aygun N, Isgor A. Innervation of the human cricopharyngeal muscle by the recurrent laryngeal nerve and external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. Langenbeck's archives of surgery. 2017 Jun:402(4):683-690. doi: 10.1007/s00423-016-1376-5. Epub 2016 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 26843022]

Okuda S, Abe S, Kim HJ, Agematsu H, Mitarashi S, Tamatsu Y, Ide Y. Morphologic characteristics of palatopharyngeal muscle. Dysphagia. 2008 Sep:23(3):258-66. doi: 10.1007/s00455-007-9133-0. Epub 2008 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 18568287]

Murakami K, Kuroda M, Kishi K. [Variations of the constrictor pharyngeal muscles in humans]. Kaibogaku zasshi. Journal of anatomy. 1996 Dec:71(6):638-49 [PubMed PMID: 9038006]

Mesti JJ, Cahali MB. Evolution of swallowing in lateral pharyngoplasty with stylopharyngeal muscle preservation. Brazilian journal of otorhinolaryngology. 2012 Dec:78(6):51-5 [PubMed PMID: 23306568]

Clavé P, Shaker R. Dysphagia: current reality and scope of the problem. Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2015 May:12(5):259-70. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.49. Epub 2015 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 25850008]

Stokely SL, Peladeau-Pigeon M, Leigh C, Molfenter SM, Steele CM. The Relationship Between Pharyngeal Constriction and Post-swallow Residue. Dysphagia. 2015 Jun:30(3):349-56. doi: 10.1007/s00455-015-9606-5. Epub 2015 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 25920993]

Khan A, Carmona R, Traube M. Dysphagia in the elderly. Clinics in geriatric medicine. 2014 Feb:30(1):43-53. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2013.10.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24267601]

Edwards BA, White DP. Control of the pharyngeal musculature during wakefulness and sleep: implications in normal controls and sleep apnea. Head & neck. 2011 Oct:33 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S37-45. doi: 10.1002/hed.21841. Epub 2011 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 21901775]

Dewan K, Santa Maria C, Noel J. Cricopharyngeal Achalasia: Management and Associated Outcomes-A Scoping Review. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2020 Dec:163(6):1109-1113. doi: 10.1177/0194599820931470. Epub 2020 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 32571156]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBerger MH, Weiland D, Tierney WS, Bryson PC, Weissbrod PA, Shah PV, Shah RN, Buckmire RA, Verma SP. Surgical management of recurrent Zenker's diverticulum: A multi-institutional cohort study. American journal of otolaryngology. 2021 Jan-Feb:42(1):102755. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102755. Epub 2020 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 33099230]