Introduction

Colonoscopy is a diagnostic as well as a therapeutic procedure performed to evaluate the large intestine (i.e., colon, rectum, and anus) as well as the distal portion of the small intestine (terminal ileum). It is performed using a hand-held flexible tube-like device called the colonoscope, which has a high definition camera mounted at the tip of the scope, as well as accessory channels that allow insertion of equipment and fluids to cleanse the colonoscope lense and colonic mucosa. The visual data that the camera feeds to the screen helps to detect abnormalities as well as overgrowth of the colonic wall and, in turn, allows us to evaluate, biopsy, and remove mucosal lesions using different types of biopsy instruments through these accessory channels. With such immense utility, colonoscopy has moved at the forefront of making colorectal cancer an easily preventable and early detected disease over the last few decades.[1]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The gastrointestinal system is divided into the foregut, midgut, and hindgut. Respectively, the foregut consists of the mouth to the second portion of the duodenum (part of the small intestine), the midgut consists of the remaining duodenum (third and fourth portion) to about two-thirds the distance of the transverse colon and the hindgut consists of the distal one-third colon to the anus. This is important to remember when it comes to lesions and pathology throughout the colon, as this will help decide future surgical planning, especially with the colon. The part of our gastrointestinal system after the stomach is divided into the small and the large intestine. Going from proximal to distal, the small intestine is further divided into the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. The ileum ends at the ileocecal valve, which opens into the first part of the large intestine. This is called the cecum, which is a pouch-like structure and further continues as ascending colon, followed by the transverse, descending, and the sigmoid colon. The colon opens into the rectum, which terminates as the anal canal. The total distance from the anus to the cecum varies from male to female but can be generalized at around 120 cm to 160 cm. The ascending colon, hepatic flexure, and transverse colon constitute the right colon, whereas the descending colon, splenic flexure, and sigmoid make the left colon. As a general rule of thumb, the diameter of the cecum, transverse colon, and descending colon are 9 cm, 6 cm, and 3 cm, respectively. This is important to remember when navigating through a colonoscopy and identifying the location within the colon.

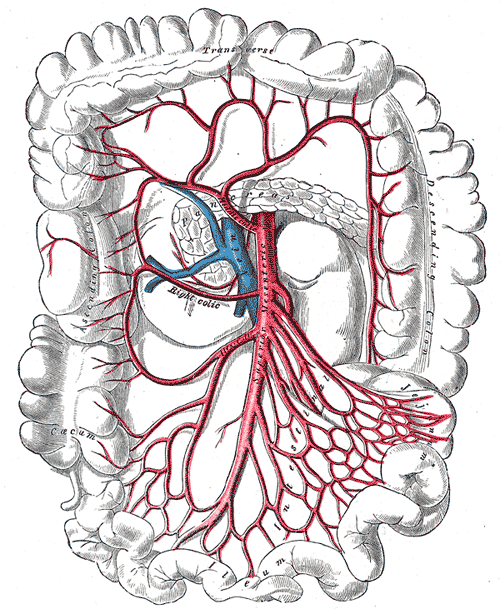

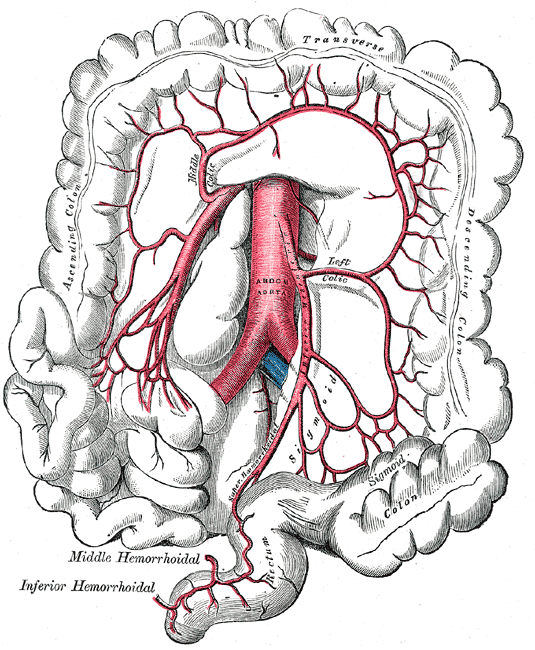

There are two primary arteries that supply the colon with blood, the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA). The SMA and IMA further branch into several other arteries that supply different components of the colon (Media 1 and 2). The small intestines, cecum, ascending colon, and proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon are supplied by the SMA, while the distal one-third, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and proximal rectum are all supplied by the IMA. Again, this is important to know when surgical intervention is required, and appropriate anatomic resections are considered.

The colon, like the small intestine, is made up of various layers (from intraluminal to extraluminal):

- Mucosa

- Submucosa

- Muscularis

- Serosa

While there are several particular notable differences between the large and small intestines, one important difference between the two is the organization of the muscularis layers. The muscularis layer is composed of circular muscle fibers and longitudinal muscle fibers. Unlike the small intestine, where these fibers run throughout the intestinal wall, the longitudinal layer is clustered into three bandlike structures called the taenia coli. In addition, the colon contains outpouchings call haustra. This can be important to remember when performing a colonoscopy as these haustra do make folds throughout the colon that can harbor polyps easily missed if not properly visualized.

The length and diameter of the colon are important when it comes to colonoscopies. The estimated lengths are listed below:

- Anal canal: 4 cm

- Rectum: 15 cm

- Sigmoid colon: 50 cm

- Descending colon: 10 cm

- Transverse colon: 50 cm

- Ascending colon 10 cm

- Cecum: 5 cm

Despite generalized estimates of length, it is the various landmarks and differences in colonic caliber, color tones, vasculature, and anatomy that helps direct location, as the colonoscope can loop on itself and not provide an accurate length measurement.

Indications

Colonoscopy can be performed for multiple reasons. It can be divided into diagnostic and therapeutic indications. Diagnostic indications can further be classified as screening vs. elective. Screening colonoscopies are performed to assess for colorectal cancers based upon a patient's risk (average vs. high). Average risk screening starts at the age of 50 and is performed at least every 10 years, as long as the colonoscopy results were unremarkable or no pathology identified that would place the patient at a higher risk. Patients will receive a repeat colonoscopy at 10-year intervals to continue to screen for colorectal cancer or pre-malignant lesions. The subsequent colonoscopies are called surveillance colonoscopies. Earlier surveillance is performed depending on the results of the first (index) procedure.

Patients with a high risk of developing colorectal cancer receive the screening procedure before the age of 50 years, and it is repeated every 1, 2, or 5 years based upon the primary risk and findings during the procedure. Examples of high-risk populations include a history of inflammatory bowel disease, a family history of colorectal cancer at age <60 years, hereditary polyposis (Such as Peutz Jegher syndrome and Familial Adenomatous Polyposis, caused by an APC gene mutation) and non-polyposis syndromes (LYNCH I and II), and surveillance after resection of colorectal cancer. Individuals with first degree relatives diagnosed with colon cancer are encouraged to undergo their first colonoscopy at age 40, or 10 years prior to the age the relative was diagnosed, whichever comes first. Elective colonoscopy is performed for reasons such as known or occult gastrointestinal bleeding or stool positive for occult blood, unexplained changes in bowel habits, patterns, iron deficiency anemia or weight loss in elderly patients, persistent abdominal pain, suspected inflammatory or infectious colitis and barium enema showing radiographic structural abnormalities.

Therapeutic indications for colonoscopy include, but are not limited to, excision and ablation of lesions, treatment of bleeding lesions, dilation of stenosis or strictures, foreign body removal, decompression of colonic volvulus or megacolon and palliative management of known neoplasms.[1][2]

The United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) is an organization that provides recommendations for medical therapies and procedures. According to recommendations, patients ages 50-75 years at average risk for colorectal cancer should undergo colonoscopy every 10 years (Grade A recommendation).[3] Other screening modalities are also available, including fecal occult blood tests (FOBT) yearly with flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years, and fecal immunochemical testing, however, that is beyond the scope of this paper and usually reserved for patients at average risk of colorectal cancer. These screening modalities are contraindicated in high-risk populations.[4]

While colonoscopy is very useful in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer, it is also used for the diagnosis, treatment, and planning for surgical interventions of certain inflammatory, mechanical, and anatomic diseases. Some examples include Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, Ogilvie syndrome, diverticulitis, and sigmoid volvulus.

Contraindications

While colonoscopy is used to help diagnose acute or chronic pathology, some contraindications do exist and should be considered when deciding to proceed with a colonoscopy. Naturally, a willing patient is always needed in order to proceed with any procedure, especially a colonoscopy. The bowel preparation, discussed elsewhere in this article, can be uncomfortable and difficult to tolerate if the patient has little desire to proceed. In addition, active inflammation should be considered when deciding to proceed with a colonoscopy. This can include inflammation from toxic megacolon, fulminant colitis, ulcerative colitis, Crohn flairs, diverticulitis, and more.

Because colonoscopy increases colonic dilation and intraluminal pressure, the chance of injury to inflamed and friable tissue is increased, and the risk of perforation enhanced. This must be considered when deciding to proceed with a colonoscopy. In general, if colonoscopy can wait until the inflammation subsides, this practice should be employed. Absolute contraindications to colonoscopy include patient refusal, recent myocardial infarction, hemodynamic instability, peritonitis, recent surgery with colonic anastomosis, or bowel injury and repair. In general, patients should wait at least 6 weeks from acute events before proceeding with a colonoscopy.

Equipment

A colonoscopy does require the use of particular instruments and a team of individuals knowledgable about the procedure. A colonoscopy suite will be equipped with high definition monitors, an insufflation device that produces positive pressure within the intestinal lumen, a suction device, several different grasping instruments, and equipment needed for providing irrigation to the intestine.

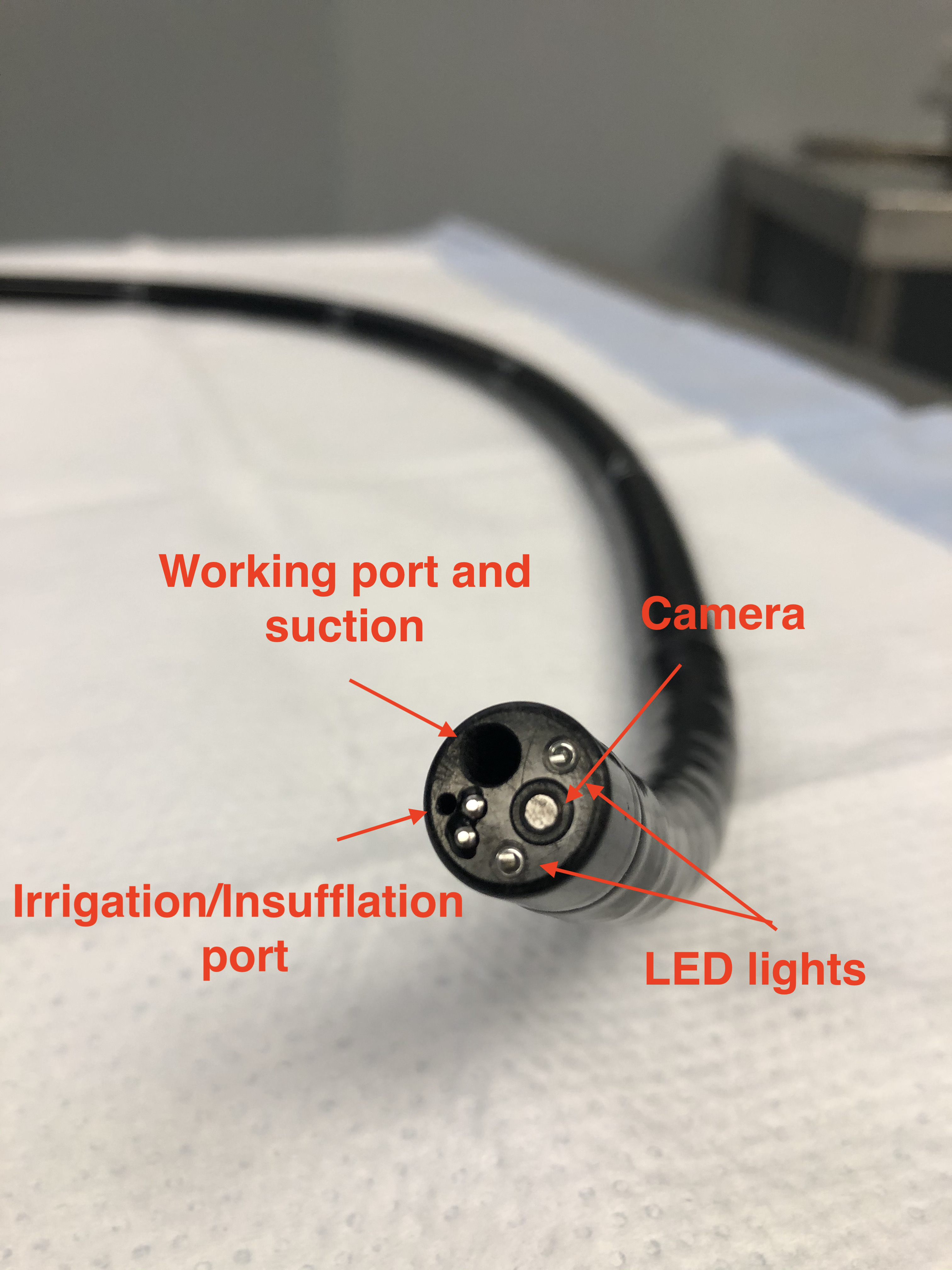

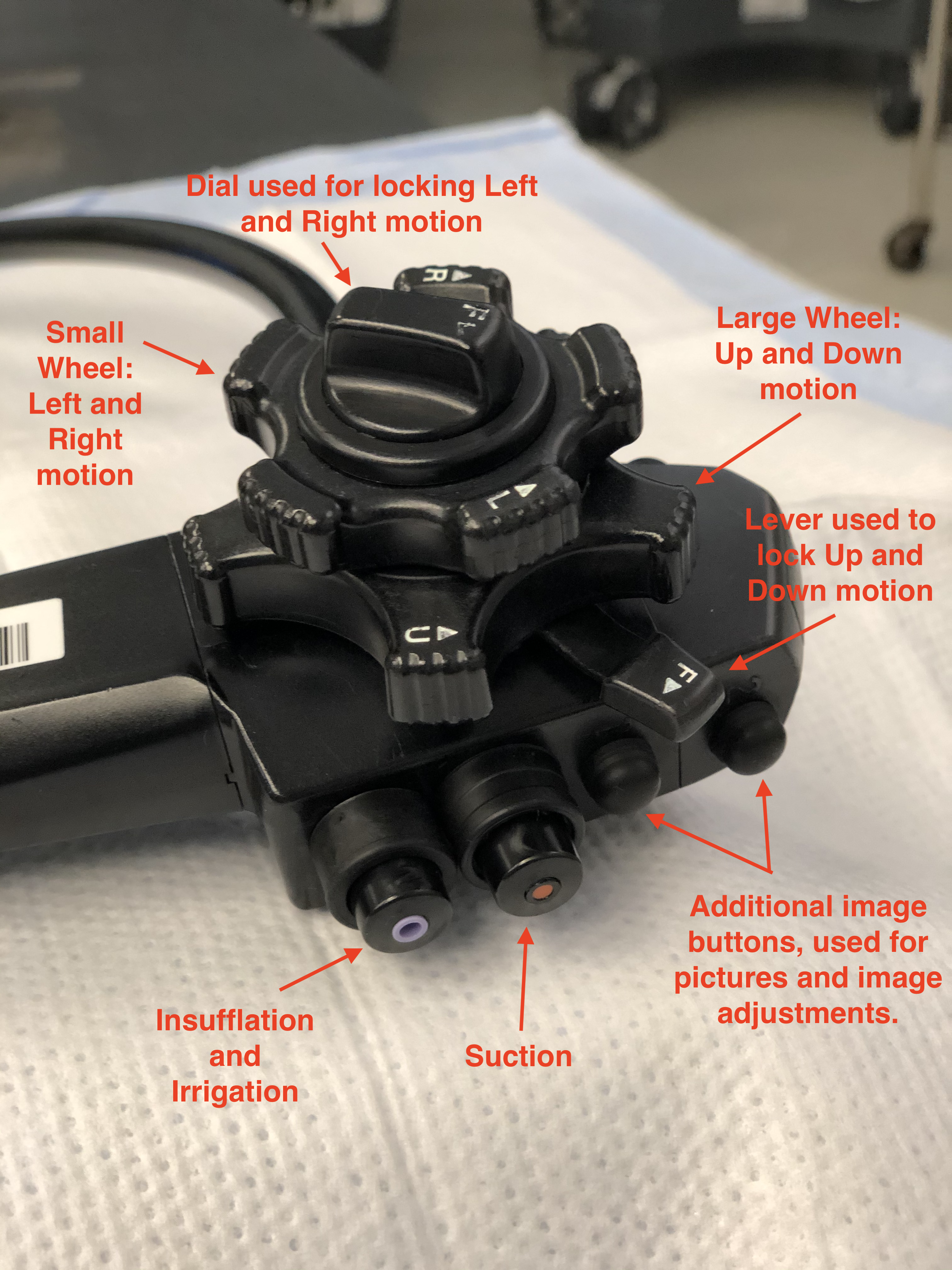

A colonoscope is a long cylindrical tube that is flexible, durable, able to be cleaned, and can be manipulated by a single individual. There are pediatric and adult-sized endoscopes. The length of the scope is roughly 160 cm - 180 cm with, a diameter of about 1.0 cm to 1.2 cm, depending on the manufacturer and scope size. At the end of the colonoscope, there are several vital working parts. These include anywhere from two to three lenses to help provide depth and clarity to images, two light-emitting diodes (LED) that allow for appropriate illumination of the colonic mucosa, and two small holes that function as working ports to pass irrigant and instruments through (Image 4).

The colonoscope has a handle that is intended to be held with the left hand, while the right hand manipulates and advances/withdraws the scope near the anus. At the base of the handle, depending on the brand of scope, there is a dial to increase or decrease the rigidity of the scope. This allows for maneuvering through difficult corners and applying various degrees of tension during push and pull of the colonoscope. Too much rigidity can increase patient discomfort and increase the risk of perforation, so caution should be used when increasing this too much during the colonoscopy. Also attached to the handle are several working instruments that allow for manipulation of the tip of the scope, adjusting image quality and controlling various videography options during the colonoscopy (record, freeze frame, picture, zoom, etc.). Two notable controls on the scope are the wheels attached to the right of the handle. These are intended to be manipulated with the thumb and index finger of the left hand, although the right hand can assist if needed. The larger wheel, located proximal to the handle allows for the upward and downward motion of the scope, while a smaller wheel located distal to the handle allows for left and right movements of the scope. These, together with the rotational aspect of the colonoscope, allows for a wide degree of motion and movement that allows for better visualization of the colon. The head of the scope without movement has a viewing angle of anywhere from 140 degrees to 170 degrees, depending on the scope model and manufacturer. This, in conjunction with the movement of the end of the scope, allows for a nearly 360-degree view in all directions. It is also important to note that proximal and distal to the two wheels are two switches that are used to lock the up/down, left/right features of the scope. It is important that before starting the procedure that these switches are released, and the tip of the scope moves freely before inserting it into the anus. Failing to do so can cause discomfort to the patient and damage the sensitive tissue to the anus. In addition, this will complicate the procedure and make maneuvering the scope through tight junctions and turns more difficult; this increases the risk of accidental perforation. Please see images 3-7 for visualization of a colonoscopy.

The two small holes, as previously mentioned, allow for the passing of equipment and irrigation. These working ports are crucial for the successful visualization and therapeutic effects of a colonoscopy. Long wires and instruments can be inserted into the working port. This includes graspers, needles, snares, and clip appliers. The purpose of such allows for a wide variety of therapies, including stopping a bleeding vessel, removing a suspicious polyp, tattooing a mass for future surgical planning, or cauterizing concerning and bleeding tissue.

Personnel

For patient safety, it is important that the appropriate personnel are in the room assisting an experienced clinician with the procedure. This would include, at a minimum, a nurse for medication administration and a technician that can assist with equipment setup, patient positioning, and troubleshooting. Having the extra set of hands allows for assistance in manipulating the patient and providing counter pressure on the abdomen when needed. Having an experienced assistant has been shown to improve patient satisfaction and colonoscopy success.[5] It is possible for colonoscopies to be performed without the use of an anesthesiologist or certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA). However, this does require the colonoscopist to be familiar with medications for sedation, contraindications, and requires their attention to be divided between the procedure and the patient's comfort and sedation status. To better assist with the patients' satisfaction, an anesthesiologist or CRNA can be of assistance to help provide deep sedation, especially in patients that are obese, have tortuous colons or anatomic variations and diseases (diverticulosis).[6]

Preparation

Preparation for a colonoscopy is the biggest complaint that most patients have about receiving the procedure, and is a primary reason for non-compliance to screening colonoscopies. For a colonoscopy to successfully detect malignant or pre-malignant lesions and reduce the need for repeat colonoscopies, appropriate bowel preparation is a standard that must be achieved. Failure to have adequate bowel preparation can be considered a contraindication to proceed with the procedure, as this increases the risk of perforation and false-negative results. There are several studies available that show significantly improved outcomes in patient care and early detection of cancer with the use of an appropriately cleansed colon before a colonoscopy. This, in conjunction with several other factors, including the time to the cecum, ileocecal intubation rate, and withdrawal time, are markers that determine the success of an appropriate colonoscopy.[7]

The basis of adequate bowel preparation is quite simple; that is, the colon should be free of stool and allow for adequate visualization of the colonic mucosa. While the principle is simple, the method of achieving this can be a problematic component of colonoscopy and uncomfortable for patients. There are many different medications and oral laxatives that can be utilized in a bowel preparation regimen, including polyethylene glycol, magnesium citrate, magnesium hydroxide, bisacodyl, and sodium picosulfate. Several studies have been performed to determine the best bowel cleansing regimens. Each physician has their own regimen they have developed, and found works best for their practice. However, some factors must be considered when determining the appropriate bowel cleansing regimen. These include substance taste, quantity, gastrointestinal discomfort, and effectiveness. The Bowklean study, performed from October 23, 2013, to March 24, 2014, was organized to determine which regimen, polyethylene glycol (2 to 4 L), or picosulfate/magnesium citrate (300 mL), provided a better cleansing effect and higher patient satisfaction. Of their study, they found that patients tolerated the picosulfate/magnesium citrate solution better than the polyethylene glycol and that it provided a better bowel cleanse for adequate visualization during colonoscopy.[8]

While the colon must be clean, it will never be fully cleared of stool. It should be explained to patients that they will still produce stool and that it may yet have some color to it. The key to the bowel cleanse is that the stool is liquid and can be quickly cleared using the irrigation function of a colonoscope. To date, there is no ideal cleansing regimen that is without discomfort. Patients should consume a clear liquid diet the day before the procedure. This, in conjunction with the chemical cleansing agent, provides the highest chance for a successful colonoscopy. For patients that cannot tolerate a 24-hours cleanse, it is possible that they can proceed with a clear liquid diet for up to three days before the procedure with a gentle laxative regimen to help facilitate a clean colon.

Enemas may be used before a colonoscopy, but alone, they do not provide adequate preparation and will not provide an appropriate bowel cleanse. This is primarily due to the limits of an enema and its ability to reach the transverse colon, ascending colon, and cecum. For the rectum and sigmoid colon, they may help to provide a final cleanse, but their use is limited.

Antibiotics prophylaxis for colonoscopies is a topic of much debate. While there are no hard indications that would warrant the use of prophylactic antibiotics in colonoscopies, tailoring the use of antibiotics based on patient risk factors should be entertained. A patient that is immunocompromised, or receives peritoneal dialysis, or has diabetes, may be at higher risk than the general population for peritonitis following colonoscopy and polypectomy. Consideration should be held for these patients and may be of benefit. In the general population, antibiotics are likely not indicated.[9]

At the foundation of any good medical practice, any decisions and procedures should be thoroughly explained to the patient, and any questions answered before proceeding. Especially with a colonoscopy, it is of significant benefit to sit with and discuss the procedure steps and the prescribed bowel preparation. Studies have shown that this method of teaching provides a more successful bowel preparation than simply providing a pamphlet or handout alone. Incomplete bowel preparations have been reported to be as high as 10% to 20% of reported colonoscopies. By personally discussing the bowel preparation timeline and patient expectations, this increases compliance and successful colonoscopy.[10]

Technique or Treatment

Performing a colonoscopy requires practice and is a skill that is difficult to master. While watching an experienced clinician perform a colonoscopy may appear simple, the technique is something that requires time, patience, and a lot of practice. Navigating through a cylindrical tube that can flex, dilated, contract, and move is not an easy task. In addition, patient factors such as obesity, redundant colonic tissue, surgical history, compliance with bowel preparation, and underweight individuals all need to be accounted for when preparing for a colonoscopy. For a clinician to become proficient in colonoscopy, this requires several hours on a simulator, as well as proctored colonoscopies with an experienced surgeon or gastrointestinal specialist.

It is crucial that the clinician is familiar with the equipment and tests it before starting the colonoscopy. As mentioned before, there are many components to the colonoscope. Manipulating all elements (up, down, right, left, clockwise, and counterclockwise rotation) of the scope adds to the complexity of the procedure.

The patient should be positioned in the left lateral decubitus position. Although, some clinicians may prefer the patient on their back or right side if circumstances require. On the left-sided position, the patient's legs should be flexed, and pillows should be placed around their back, head, and between their knees to help prevent injury to the bony prominence and to help maintain position. The technician or nurse is there to assist with preserving stability and preventing the patient from rolling forward or backward. Also, they are there to help provide counter pressure to the abdomen to assist the endoscopist in navigating corners and turns. The legs being flexed toward the chest help to relax the puborectalis and pubococcygeus muscles. This allows for easier entry and traversing past the angle at the sacral prominence. Failure to achieve this position makes navigation past the rectum at the level of the sacrum more difficult.

The endoscopist should be standing behind the patient. Before inserting the scope, it is essential to perform a digital rectal exam (DRE) with a water-soluble lubricant. At this time, the clinician should be feeling for any lumps, bulges, rectocele, or masses. In addition, they should take note of the rectal tone but must also take into account the level of sedation the patient has achieved, as this may affect the tone of the anus. Following the DRE, The handle of the scope should be in the left hand of the clinician, and the endoscope should be placed in the right hand about 10 cm to 20 cm from the working end or lense of the scope. A generous amount of water-soluble lubricant should again be used to help prevent injury to the sensitive tissue of the anus. Using all components of the scope (up, down, left, right, and rotation), the endoscope is navigated through the different levels of the rectum, colon, and terminal ileum.

Specific landmarks can be used to help the clinician know where they are in the colon. While generalized distances of the anatomy are useful, using the scope to measure these out is not always reliable, it is important to remember that the scope can twist and turn on itself and will not provide an accurate measurement farther into the colon.

Important landmarks to remember and consider while performing a colonoscopy:

- The first portion of the rectum has three different larger outpouchings. This is important for acting as a compartment for fecal storage and allows the human body to go more extended periods without having to defecate. It is easily identified through the anus at the beginning of the colonoscopy.

- The second landmark begins at the sacral prominence. This signifies the proximal end of the rectum. It can be more difficult to traverse because the sacrum presses up against the colon, however over time and experience, it becomes easier to traverse.

- The taenia coli, as previously discussed, travels the length of the colon, it is at the end of the sigmoid colon and the beginning of the rectum that these fibers splay out and are no longer clustered in a longitudinal bandlike fashion. These Taenia coli, while not directly seen within the colon, can generally be identified secondary to the tensile forces they place on a distended bowel. They can help delineate location from rectum to sigmoid colon. This is the third landmark that can be used to identify the location.

- The descending colon contains a more round appearance to it than it does any other component of the colon. Its diameter is smaller than that of the transverse and ascending colon, approximately 3 cm to 5 cm. Continuing into the transverse colon, not only does the diameter change and increase in size, the shape of the colon becomes more triangular than round. This is primarily due to the taenia coli.

- Navigating past the splenic flexure can be another landmark that provides difficulty in traversing. Having the assistant provide counterpressure to the right upper quadrant and right lower quadrant of the abdomen can help push the endoscope past the flexure and into the transverse colon. Two techniques have been described and safe to utilize, the Prechel pressure technique, pressing the forearm into the abdomen, and the two forearm technique, both forearms are pressed into the patients' belly, should be utilized by the assistant. The open hand technique, pressing with the palm of the hand, is not recommended as it can cause injury to the assistant.[11]

- At the hepatic flexure, it can be noticed that the colon takes on a bluish hue. This is the liver reflecting into the colon and can help the clinician identify that he is near the hepatic flexure and starting to traverse into the ascending colon. It is important to note that injury to the liver can occur from too much pressure in this region, although this is rare.

- The ascending colon is much more dilated than the descending and transverse colon. It will continue to enlarge towards the cecum. A few characteristics that help to determine this location include; the opening to the appendix, the opening to the ileocecal valve and the convergence of the taenia coli into one focal spot at the end of the cecum, this is also known as the Mercedes sign and is self-explanatory. These landmarks should be utilized to help identify the cecum. While using transillumination can help to provide more information, it should not be used as a measure to come to this conclusion.

It is important that the endoscopist feels for any tension or difficulty with advancing the colonoscope. The scope should never be progressed if the view is not clear, and the lumen is not visualized. This increases the risk of injury. Should the clinician find it difficult to advance the scope, it is possible; they have developed an Alpha loop. This occurs more commonly in the sigmoid colon. Should this happen, the endoscopist may also find that the patient is becoming more uncomfortable. This is another clue that a loop has formed. To remove the loop, suction is applied, the scope is withdrawn while rotating the shaft of the scope clockwise. This will help to remove the loop and allow for further advancement of the scope. It is important to remember that sometimes to advance further, the scope must be withdrawn.

To help complete the colonoscopy and prevent any missed lesions, as well as help, provide more data that the cecum has been reached, the endoscopist should try to intubate the ileocecal valve. Not only does this help to give more information that the cecum was indeed entered, but it is also used to visualize the ilium and help diagnose inflammatory bowel disease.

While entering the colon and traversing toward the cecum, the endoscopist is examining the mucosa and looking for any lesions that are concerning. Should a polyp be identified, it should be removed, if possible, at that time. If the lesion is too large to remove, a biopsy should be obtained, and the lesion should be tattoed using India ink or methylene blue, and the location noted. However, it is not during the entrance of the colon that the bulk of the procedure is performed. Withdrawl of the colonoscope has been identified as the most important component of the procedure. It is during withdrawal that the clinician should be examining all components of the colon and looking behind all haustral folds.

Even the smallest of polyps can be identified within one of these folds, and if not appropriately identified, can result in a false negative colonoscopy and result in potentially missed cancer. As mentioned before, there are certain markers that are used to define a successful colonoscopy. It is recommended that a clinician spend no less than six to eight minutes withdrawing from the colon for it to be considered a successful colonoscopy and provide appropriate screening for the patient. Removing the scope faster than this has been found to increase the risk of missed polyps and early cancer.[12]

While withdrawing from the colon, it is vital to aspirate some of the insufflation to provide better patient recovery, less flatulence, and distention discomfort. Near the end of the colonoscopy, the anus and the dentate line should be examined for lesions or hemorrhoids via retroflection of the scope. To retroflex, the scope is brought back just past the edge of the proximal end of the anus. Using the anal canal, the scope should be advanced while rotating both wheels fully back; this allows the scope to fully retroflex in the rectum and allow for visualization of the anus. Following this maneuver, both wheels are returned to neutral, the rectum suctioned, the scope is withdrawn, and the procedure complete.

Complications

As with every invasive procedure, there are inherent complications that should be known and described to the patient before proceeding. Generic complications such as reactions to anesthesia, including stroke, heart attack, respiratory distress, and death, are always associated with sedating procedures and should be described during consent. Specific to colonoscopies, patients should be notified that there are risks of rectal tears, bleeding, pain, bloating, and infection. A more serious complication that can occur, although rare, includes intestinal perforation. The risk of perforation has been described at around 0.14% (or 1 in 1000 colonoscopies). Generally speaking, the risk of perforation with colonoscopy is particularly low, and the procedure relatively safe. This makes it an excellent screening modality for colon cancer with low risk, respectfully.[13] Perforation can occur anywhere throughout the colon and terminal ileum. But it has been described frequently that the most common site of perforation is in the sigmoid colon. Perforation occurs primarily by three different methods; Shear injury, secondary to push and pull against the colonic wall, overdistention from too much insufflation against a weakened colonic wall, and perforation via mechanical polypectomy and electrocautery.[14] Each turn or corner in the colon acts as a focal point for the scope to push against so that it can advance through the colon. Manipulation maneuvers via the assistant pushing against the abdominal wall can help mitigate some of the push and pull forces and help prevent potential injury. The sigmoid colon, being the first corner or turn in the large intestine, has the highest risk of injury as it incurs the highest amount of force as the scope advances to the cecum.

Another complication, although rare, that the clinician should be aware of includes post polypectomy electrocoagulation syndrome (PPES). When a polyp is removed, electrocautery is used to fulgurate any remaining cells that may have been left behind. While the risk of transmural burn is low, it can occur if the clinician does not lift the tissue away from the colonic wall while applying electrocautery. Patients may present with severe abdominal pain several hours following a colonoscopy in which polypectomy with electrocautery was performed. Labs may demonstrate a leukocytosis with left shift and a CT that shows distended bowel and inflammatory changes, but no signs of pneumoperitoneum. It is treated with bowel rest, supportive care, antibiotics, and resolves without any need for surgical intervention. To help reduce the chances of developing PPES, the clinician can lift the polyp away from the colonic wall during electrocautery. In addition, normal saline can be injected beneath the polyp to elevate the mucosa away from the colonic wall creating an insulating type layer.[15]

Clinical Significance

As previously mentioned, the USPSTF recommends screening colonoscopy starting at age 50 for average-risk individuals and should continue every 10 years until the age of 75. The basis for this decision stems from the understanding that for the average-risk individual, the time from polyp to cancer is estimated at around 10 years.[16][17]

During the colonoscopy, the clinician should be looking for any suspicious lesions that would warrant removal, shorten surveillance intervals, or indicate surgical and oncologic consultation. Any suspicious polyps that are identified should be removed and sent to pathology. In general, hyperplastic polyps harbor little to no risk for colorectal malignancy. Adenomas, on the other hand, are considered suspicious lesions and should be removed if > 6 mm or harbor concerning features. The method of removal depends on the size and shape of the polyp. Pending polyp size and appearance, the endoscopist should consider tattooing the location so that it may be more easily identified on repeat colonoscopy or for surgical intervention.

In the United States, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related death in both men and women. This primarily stems from the western lifestyle of red meat, low fiber diets, smoking, alcohol use, and consumption of highly processed foods.[18] Screening colonoscopy has been found to significantly reduce the mortality of colorectal cancer through early detection and intervention. It is important that clinicians are familiar with screening guidelines and encourage patients to start colonoscopy screening at age 50 if average risk or 10 years prior to the age of a known relative with CRC, whichever comes first.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patient care is a collaborative effort by many specialized individuals. The forefront of this force is the primary care provider (PCP). They have established relationships with patients and see them on a more regular basis than a specialist would. It is important that the PCP see their patients yearly to help maintain health practices and keep up to date on recommended guidelines for their patients. PCP's should recommend screening for CRC as appropriate by current up to date recommendations, both for high-risk and average-risk patients. As previously discussed, the significant challenges that successfully impact compliance with recommended CRC screening are patient comfort with bowel preparation and the vulnerability of the procedure. Many studies have been developed to help fashion a solution to help encourage patients to pursue screening procedures. However, results have shown that even increasing collaborative efforts among health care professionals still results in non-compliance with recommended colonoscopy screenings.[19] [Level 2]

Some studies have shown that while colonoscopy provides a visual inspection of the entire colon, it may not be the best means for screening. Other possible adjuncts to testing average-risk patients include an annual or biennial fecal occult blood test in addition to a flexible sigmoidoscopy every five years. This has possibly been shown to be as effective, if not better, than colonoscopy every ten years. With it being a less invasive procedure requiring a more tolerable bowel preparation (enema vs. oral bowel cleanse), patients may be more inclined to follow screening guidelines and collaborative efforts among PCP's more successful.[2] [Level 5] The specifics between colonoscopy, FOBT with flexible sigmoidoscopy, fecal DNA testing for CRC is beyond the scope of this paper.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Superior and Inferior Mesenteric Arteries. This image shows the anatomic relationships between the abdominal aorta; ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colonic segments; rectum, right, left, and middle colic arteries; superior and inferior mesenteric arteries; and superior, middle, and inferior hemorrhoidal arteries.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Telford JJ. Inappropriate uses of colonoscopy. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2012 May:8(5):342-4 [PubMed PMID: 22933868]

Tinmouth J, Vella ET, Baxter NN, Dubé C, Gould M, Hey A, Ismaila N, McCurdy BR, Paszat L. Colorectal Cancer Screening in Average Risk Populations: Evidence Summary. Canadian journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2016:2016():2878149. doi: 10.1155/2016/2878149. Epub 2016 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 27597935]

D'Andrea E, Ahnen DJ, Sussman DA, Najafzadeh M. Quantifying the impact of adherence to screening strategies on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Cancer medicine. 2020 Jan:9(2):824-836. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2735. Epub 2019 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 31777197]

Buskermolen M, Cenin DR, Helsingen LM, Guyatt G, Vandvik PO, Haug U, Bretthauer M, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I. Colorectal cancer screening with faecal immunochemical testing, sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy: a microsimulation modelling study. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2019 Oct 2:367():l5383. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5383. Epub 2019 Oct 2 [PubMed PMID: 31578177]

Fu L, Dai M, Liu J, Shi H, Pan J, Lan Y, Shen M, Shao X, Ye B. Study on the influence of assistant experience on the quality of colonoscopy: A pilot single-center study. Medicine. 2019 Nov:98(45):e17747. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017747. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31702625]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBall AJ, Rees CJ, Corfe BM, Riley SA. Sedation practice and comfort during colonoscopy: lessons learnt from a national screening programme. European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2015 Jun:27(6):741-6. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000360. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25874595]

Tinmouth J, Kennedy EB, Baron D, Burke M, Feinberg S, Gould M, Baxter N, Lewis N. Colonoscopy quality assurance in Ontario: Systematic review and clinical practice guideline. Canadian journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2014 May:28(5):251-74 [PubMed PMID: 24839621]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHung SY, Chen HC, Chen WT. A Randomized Trial Comparing the Bowel Cleansing Efficacy of Sodium Picosulfate/Magnesium Citrate and Polyethylene Glycol/Bisacodyl (The Bowklean Study). Scientific reports. 2020 Mar 27:10(1):5604. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62120-w. Epub 2020 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 32221332]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWu HH, Li IJ, Weng CH, Lee CC, Chen YC, Chang MY, Fang JT, Hung CC, Yang CW, Tian YC. Prophylactic antibiotics for endoscopy-associated peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients. PloS one. 2013:8(8):e71532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071532. Epub 2013 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 23936514]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSu H, Lao Y, Wu J, Liu H, Wang C, Liu K, Wei N, Lin W, Jiang G, Tai W, Guo C, Wang Y. Personal instruction for patients before colonoscopies could improve bowel preparation quality and increase detection of colorectal adenomas. Annals of palliative medicine. 2020 Mar:9(2):420-427. doi: 10.21037/apm.2020.03.24. Epub 2020 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 32233640]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePrechel JA, Hucke R. Safe and effective abdominal pressure during colonoscopy: forearm versus open hand technique. Gastroenterology nursing : the official journal of the Society of Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates. 2009 Jan-Feb:32(1):27-30; quiz 31-2. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0b013e3181972c03. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19197187]

Leddin D, Lieberman DA, Tse F, Barkun AN, Abou-Setta AM, Marshall JK, Samadder NJ, Singh H, Telford JJ, Tinmouth J, Wilkinson AN, Leontiadis GI. Clinical Practice Guideline on Screening for Colorectal Cancer in Individuals With a Family History of Nonhereditary Colorectal Cancer or Adenoma: The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Banff Consensus. Gastroenterology. 2018 Nov:155(5):1325-1347.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.017. Epub 2018 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 30121253]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDulskas A, Smolskas E, Kildusiene I, Maskelis R, Stratilatovas E, Miliauskas P, Tikuisis R, Samalavicius N. Outcomes of surgical management of iatrogenic colonic perforation by colonoscopy and risk factors for worse outcome. Journal of B.U.ON. : official journal of the Balkan Union of Oncology. 2019 Mar-Apr:24(2):431-435 [PubMed PMID: 31127987]

Lim DR, Kuk JK, Kim T, Shin EJ. The analysis of outcomes of surgical management for colonoscopic perforations: A 16-years experiences at a single institution. Asian journal of surgery. 2020 May:43(5):577-584. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2019.07.013. Epub 2019 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 31400954]

Jehangir A, Bennett KM, Rettew AC, Fadahunsi O, Shaikh B, Donato A. Post-polypectomy electrocoagulation syndrome: a rare cause of acute abdominal pain. Journal of community hospital internal medicine perspectives. 2015:5(5):29147. doi: 10.3402/jchimp.v5.29147. Epub 2015 Oct 19 [PubMed PMID: 26486121]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceU.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: recommendation and rationale. Annals of internal medicine. 2002 Jul 16:137(2):129-31 [PubMed PMID: 12118971]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSummers RM. Polyp size measurement at CT colonography: what do we know and what do we need to know? Radiology. 2010 Jun:255(3):707-20. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10090877. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20501711]

Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Primary prevention of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010 Jun:138(6):2029-2043.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.057. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20420944]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShaw EK, Ohman-Strickland PA, Piasecki A, Hudson SV, Ferrante JM, McDaniel RR Jr, Nutting PA, Crabtree BF. Effects of facilitated team meetings and learning collaboratives on colorectal cancer screening rates in primary care practices: a cluster randomized trial. Annals of family medicine. 2013 May-Jun:11(3):220-8, S1-8. doi: 10.1370/afm.1505. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23690321]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence