Introduction

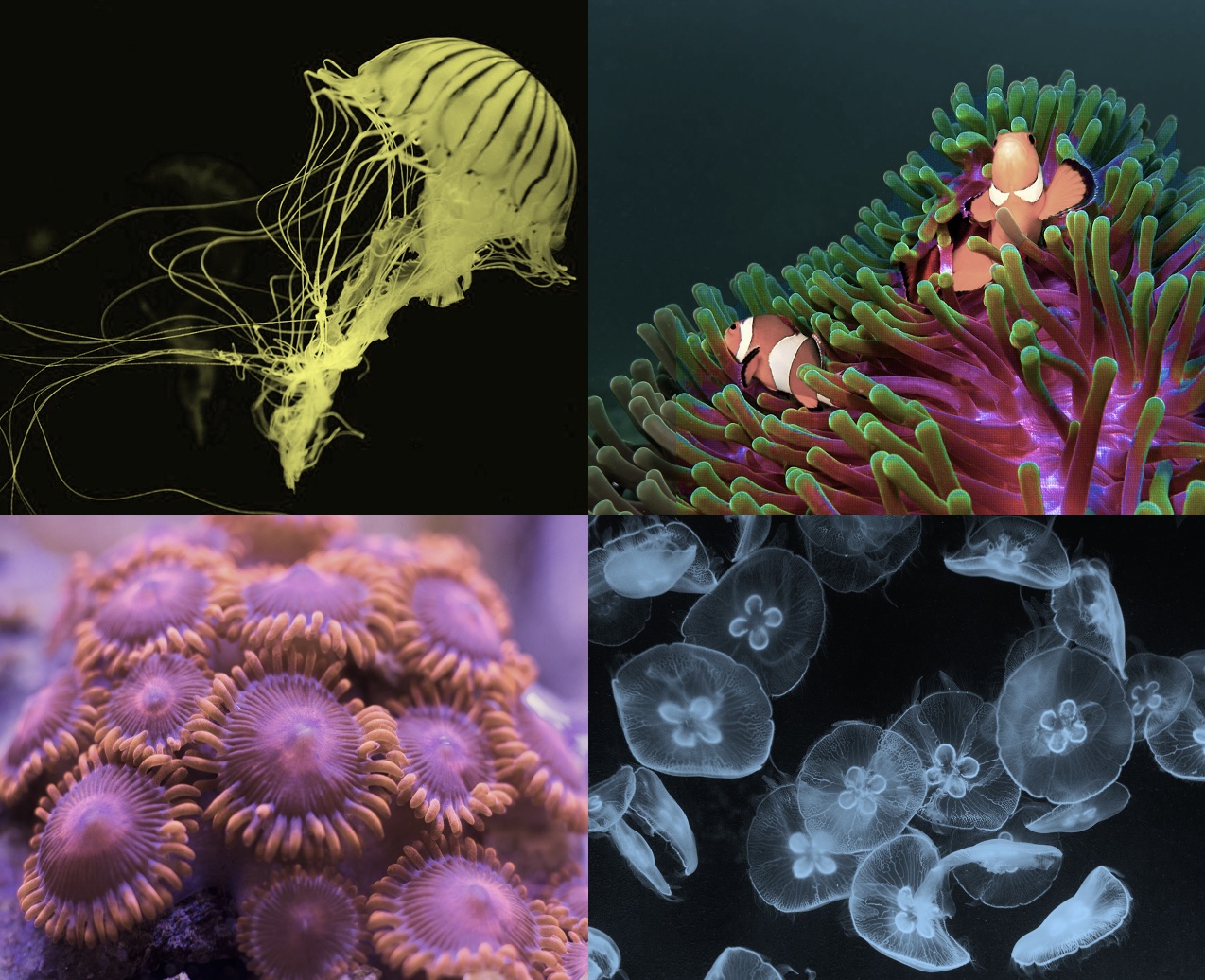

Cnidaria is a classification of marine life that includes jellyfish, fire coral, stinging hydroids, sea wasps, sea nettle, and anemones. Jellyfish not only cause most marine envenomations in the United States but also worldwide due to the large numbers. The severity and treatment of their stings vary widely. Factors that determine the severity of a bite include the type of jellyfish, the size of the sting, and the individual patient.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Jellyfish are members of the phylum Cnidaria. They are invertebrates that float in salt and brackish water. They have a central bell and multiple lengthy tentacles. Jellyfish consume their prey using stinging cells called nematocysts. Nematocysts are hollow, barbed tubes that inject venom into the victim's skin at a force of two to five pounds per square inch (13-34 kPa). The nematocysts are located along the jellyfish's tentacles and discharge using a “spring mechanism” upon contact with the prey.[1] The stinging mechanism can still function even if the organism is dead. The venom enters through the dermal layer, and may also penetrate the general circulation causing both skin and systemic symptoms in affected patients. The venom is antigenic and commonly causes allergic reactions. Jellyfish stings occur when humans wander into their path, as jellyfish do not actively seek out prey.

Epidemiology

Jellyfish stings are common in warm coastal waters, with most stings being mild. There have been two reported deaths from the Portuguese Man-Of-War. Some of the more severe bites are associated with the box jellyfish, specifically Chironex Fleckeri. This jellyfish is commonly known as the “sea wasp.” The sea wasp has caused multiple deaths along the Australian coastlines. The sting of this jellyfish can induce cardiac arrest within minutes.[2] The sea wasp is more dangerous than the Great White shark!!

History and Physical

At the time of the sting, most patients do not see the jellyfish but do feel immediate pain. Usually, patients will notice a linear red or urticarial lesion that develops a few minutes after the exposure.[2] Sometimes these lesions can be delayed by several hours. The pain associated with the envenomation is described as burning pain and sometimes as pruritus. The pain may last anywhere from several hours to several days. Moderate to severe symptoms include muscle ataxia, seizure, anaphylaxis, hypotension, bronchospasm, pulmonary edema, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle cramps, conjunctivitis, and corneal ulcers.

There's also a specific syndrome called Irukandji syndrome. This syndrome is caused by a tiny jellyfish which is usually one centimeter by one centimeter in diameter. Symptoms of this syndrome include pain at the site of envenomation followed by generalized back, chest, abdominal pain, hypertension, and tachycardia. The signs are a result of a catecholamine release. [2]

Another common manifestation is called seabather’s eruption. This itchy dermatitis caused by the sting of a jellyfish and sea anemone larva.[3] The substance gets caught in the patient’s bathing suit causing local skin irritation.

The Portuguese Man-Of-War is not a true jellyfish, but a colony of hydroids. Envenomation causes pain, scarring, paresthesias — other symptoms include nausea, headache, chills, and possibly even cardiopulmonary arrest.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of jellyfish envenomation is a clinical one. Key elements of the history include the time of envenomation, the body part that was involved, activity when stung, type of water, geographic location, and the onset of symptoms. Workup includes a careful history and assessment of the ABCs. Then you perform a thorough secondary exam and complete skin evaluation.

Treatment / Management

Treatment should start with immediate removal of the nematocysts. This removal can be done using gentle pressure with a credit card. Shaving cream or a baking soda slurry can be used to help remove the nematocysts as well. Care should be used to avoid using too much pressure as it can cause the nematocyst to release their toxin. You should not immerse the wound in freshwater, because this may cause the nematocysts to discharge more venom due to differences in oncotic pressures.[2] You can soak the wound in saltwater to help relieve some of the pain.(B3)

Treatment also varies by the type of jellyfish involved. For most jellyfish in the US, hot water immersion is effective at decreasing the pain of the sting. You should use the hottest water that can be tolerated by the patient, without burning the skin. You can also use acetic acid (household vinegar) to help relieve pain.[2] The toxin is reduced by soaking the affected area of the body for 30 minutes in the 5% acetic acid. Topical anesthetics can also be used once all the nematocysts have been removed. For severe pain, narcotic medication may be provided. Corticosteroids can be used for severe symptoms. Antihistamines may be used for itching. The patient should have their tetanus vaccination updated while in the Emergency Department as well. Patients that appear to have symptoms consistent with anaphylaxis should be treated just as you would normally treat anaphylaxis from any other source.[4](B3)

There are urban myths that urine can help decrease the pain of a jellyfish sting.[1] At this time there is no evidence to supports this, and therefore is not recommended.

For unstable or patients in cardiac arrest that have been stung by Chironex fleckeri (sea wasp), it is advised to administer the antitoxin. The starting dose is one vial or 20,000 units. This can be repeated to a maximum of six vials. The effects of the antivenom may be delayed by as much as 60 to 70 minutes making prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation necessary.[5] (B3)

Treatment of seabather's eruption consists of symptomatic treatment. Antihistamines such as diphenhydramine, loratadine, or hydroxyzine can be used to help with the itching.[3] Topical calamine lotion can also be used to help with pruritus.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis should include cellulitis, gastroenteritis, and envenomation from other marine life (corals, sea urchins, fish, and stingrays).

Prognosis

Prognosis is generally good for mild stings as these usually only require supportive care. Severe bites or stings from Cnidaria with more potent toxins can have more life-threatening complications. These stings should be treated aggressively with resuscitation protocols and antivenom.[2]

Complications

Complications of Cnidaria stings can range from minor symptoms to life-threatening symptoms. These complications from envenomation include cellulitis, abscess, allergic reactions, anaphylaxis, and cardiorespiratory arrest.[2]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Several over-the-counter options are available to prevent jellyfish envenomation. These range from suits worn by swimmers and surfers to lotions that mimic the mucus coating that is found on clownfish.

Patients that appear well and have no signs of systemic illness may be discharged home with return precautions for any symptoms of anaphylaxis. Patients that do show signs of significant systemic symptoms, or need antivenom, should be admitted to the hospital for further symptomatic management.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Cnidaria generally stings only require supportive care. Severe stings may require interprofessional care. In the case of severe stings, the practitioner should be aware of local marine life and know the complications of specific envenomation. Calling the local lifeguards who may be the first medical professional to see the patient may give you some insight as to what could have caused the scene. Nursing staff should be watching for complications of severe stings including anaphylaxis and sudden cardiac arrest.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Montgomery L, Seys J, Mees J. To Pee, or Not to Pee: A Review on Envenomation and Treatment in European Jellyfish Species. Marine drugs. 2016 Jul 8:14(7):. doi: 10.3390/md14070127. Epub 2016 Jul 8 [PubMed PMID: 27399728]

Berling I, Isbister G. Marine envenomations. Australian family physician. 2015 Jan-Feb:44(1-2):28-32 [PubMed PMID: 25688956]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuevara BEK, Dayrit JF, Haddad V Jr. Seabather's eruption caused by the thimble jellyfish (Linuche aquila) in the Philippines. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2017 Oct:42(7):808-810. doi: 10.1111/ced.13196. Epub 2017 Jul 10 [PubMed PMID: 28691190]

Pereira JCC,Szpilman D,Haddad Junior V, Anaphylactic reaction/angioedema associated with jellyfish sting. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2018 Jan-Feb; [PubMed PMID: 29513832]

Andreosso A, Smout MJ, Seymour JE. Dose and time dependence of box jellyfish antivenom. The journal of venomous animals and toxins including tropical diseases. 2014:20():34. doi: 10.1186/1678-9199-20-34. Epub 2014 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 25161664]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence