Introduction

Congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform erythroderma and limb defects syndrome, also known as CHILD syndrome, is a rare genetic condition that can affect various parts of the body. Dr. Otto Sachs first described this disease in 1903 when he summarized his examination of an 8-year-old girl with the condition.[1] Other case reports have been published since then.[2][3] In 1980, Happle et al proposed the acronym "CHILD" for "congenital hemidysplasia, ichthyosiform erythroderma, and limb defects," the main manifestations evident in patients with this condition.[4][5]

CHILD syndrome is an X-linked, dominant disorder with a male-lethal trait. Most surviving patients are females, though some males may also present with the condition. CHILD syndrome presumably results from mosaicism inactivating the NAD(P)-dependent steroid dehydrogenase-like (NSDHL) protein gene, leading to decreased or absent 3-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase function.[6]

The NSDHL gene encodes 3-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, which is involved in cholesterol biosynthesis. Cholesterol has many functions in the body, as it is a crucial component of cell membranes. Cholesterol-based hormones include the glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids, and sex hormones. Cholesterol in myelin is critical to nerve impulse transmission.

CHILD syndrome should be suspected at birth if a unilateral epidermal nevus or dermatosis is found during a newborn's physical examination. Other common features include unilateral limb defects and skin lesions, unilateral ichthyosiform erythroderma, inflammatory variable epidermal nevus, and congenital heart disease.[7][8] CHILD syndrome is detected in 1 in 100,000 live births.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

CHILD syndrome has an X-linked dominant mode of inheritance. The condition involves a mutation in the NSDHL gene, located on the long arm of the X chromosome at position 28 (Xq28). This gene encodes for the enzyme 3-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, which is involved in cholesterol biosynthesis. Several NSDHL mutation types, such as nonsense and missense, have been reported, with the net effect being loss of gene function.[9][10] Some studies suggest that the unilateral manifestations of CHILD syndrome may be due to abnormal sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling during embryogenesis resulting from impaired cholesterol processing.[11] The emopamil binding protein (EBP) gene has also been reported as a cause of CHILD syndrome in some patients. EBP is also critical to cholesterol biosynthesis.[12]

Epidemiology

Fewer than 100 CHILD syndrome cases have been reported in the literature. The disorder is often lethal to males, who die in utero. Thus, almost all patients presenting with CHILD syndrome are females.

The condition is typically inherited in an X-linked dominant fashion. However, some cases of in-utero variation have been documented, indicating that inheritance of the condition may be more complicated. One male reported to have CHILD syndrome had a normal 46 XY karyotype. Happle et al explained that this patient may have had an early somatic mutation. Features of the condition are evident at birth and persist throughout life.

Pathophysiology

The enzyme 3-beta-hydroxy sterol dehydrogenase is vital to cholesterol synthesis. A deficiency of this enzyme leads to the accumulation of cholesterol biosynthetic pathway intermediates. In CHILD syndrome, cholesterol's roles in fetal development are compromised. One of those roles is the facilitation of SHH protein signaling during limb development and organogenesis, which is thought to underlie the unilateral presentation of this syndrome.[13][14]

Cholesterol is also critical to the proper formation of cell membranes and nerve myelin. Unilateral dermatosis is reported in many cases of CHILD syndrome. Neurologic abnormalities occasionally manifest, including meningomyelocele and ipsilateral brain, cranial nerve, and spinal cord hypoplasia.[15][16][32]

Histopathology

Microscopic examination of the skin lesions of patients with CHILD syndrome reveals a psoriasiform epidermis with hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. Acanthotic and papillomatous epidermis with alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis are also found.[17] Keratinocyte markers significantly differ between the affected and unaffected cells of patients with CHILD syndrome. This finding strongly suggests that the keratinocyte pathology in these patients is inherent.

The papillary dermis frequently has foam cells expressing surface markers like CD68 and CD163 but lack pan-cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and S100 proteins. CD68 and CD163 are specific for macrophages, while AE1/AE3 and S100 are epithelial markers. Under electron microscopy, the superficial dermal foam cells contain numerous lipid droplets and vacuoles, signifying the accumulation of cholesterol intermediates in macrophages.

Mi et al confirmed these histopathological features in their 2015 report about a patient with CHILD syndrome with macrophage-derived foam cells on microscopy.[18] Some studies have noted a superficial perivascular infiltrate in histopathologic skin specimens from patients with CHILD syndrome.[19]

History and Physical

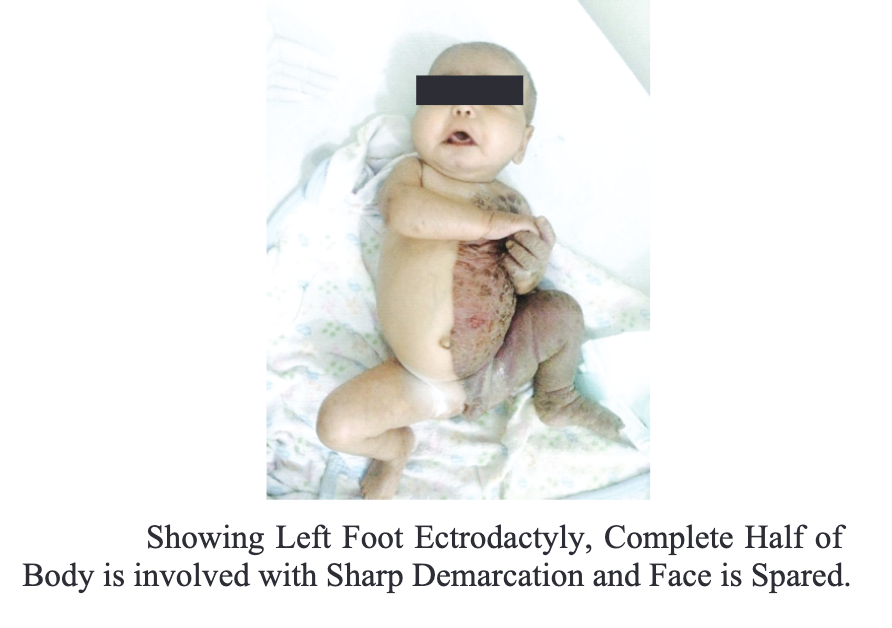

The symptoms of CHILD syndrome are often apparent at birth, affecting multiple systems and organs unilaterally (see Image. Five-Month Old Female With CHILD Syndrome). Patients have congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, which appears as thickened, red skin with waxy, yellow-colored scales.[20] The right side of the body is twice as likely to be affected than the left. Unilateral erythematous skin plaques are sharply demarcated at the midline, often sparing the face.[21]

Symptoms may not be evident at birth in some patients. Manifestations may appear as late as 9 years of age.[33]

Other dermatologic findings include unilateral ptychotropism (unilateral body fold involvement), verruciform xanthomas, onychodystrophy, and scarring alopecia.[22] Decreased erythema and more hyperkeratosis and ptychotropism are observed later in infancy. Hyperkeratosis is seen in 30% to 79% of patients.

Patients may present with limb defects ipsilateral to the skin lesions, ranging from mild contractures to hypoplasia and agenesis. Such musculocutaneous abnormalities can cause scoliosis and movement difficulty.[23] Radiographic epiphyseal stippling is a common diagnostic feature of CHILD syndrome, reported in 80% to 99% of cases.[24] Epiphyseal stippling may be associated with cholesterol biosynthesis. However, this finding usually resolves in late childhood.

Cardiovascular and neurologic malformations, if present, are also ipsilateral to the dermatosis and may lead to early death.

Evaluation

Sterol analysis shows elevated levels of C4-methylated and C4-carboxy sterol intermediates arising from NAD[P]H steroid dehydrogenase-like protein defects. Imaging tests, particularly x-rays, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), must be performed to detect skeletal and visceral abnormalities. Early identification of musculoskeletal or visceral problems allows for timely interventions. [24]

DNA sequence analysis can confirm the condition by finding the NSDHL gene defect. A biopsy of the dermatologic lesions will show lipid-laden dermal foam cells. Cholesterol levels are usually normal in patients with CHILD syndrome.[25]

Treatment / Management

Management plans are personalized based on the presentation. Skin treatments vary from topical tretinoin for localized symptoms to systemic retinoids for widespread lesions.[26] Studies on the benefits of corticosteroids and emollients have not provided convincing results, though these formulations are often used as adjuncts to other treatments.[27](B3)

Other skin treatment options include topical 2% lovastatin or simvastatin with topical cholesterol to improve skin cholesterol levels. Topical ketoconazole can relieve dermatosis by inhibiting the enzymes involved in cholesterol biosynthesis.[28][29][30][31](B3)

Patients must see different specialists for organ-specific problems. For example, individuals with limb defects must consult an orthopedic surgeon to correct existing asymmetry or dysfunction and prevent complications. Children with cardiac abnormalities must be seen by a pediatric cardiologist. Patients with neurologic symptoms must follow up with a neurologist. Dermatologists should be consulted to manage the skin problems arising from CHILD syndrome.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of CHILD syndrome includes the following:

- Epidermal nevus

- Sebaceous nevus

- Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN)

- Phacomatosis pigmentokeratotica

- X-linked dominant chondrodysplasia punctata

A thorough medical examination can help distinguish these conditions from CHILD syndrome.

Prognosis

The dermatologic symptoms of CHILD syndrome improve with age. Patients with left-sided involvement tend to have a poorer prognosis, as visceral abnormalities are more common. Association with neurologic, pulmonary, and cardiac dysfunction also worsens the prognosis.

Complications

The complications of CHILD syndrome depend on the organ systems involved. Squamous cell carcinoma has been reported in a 33-year-old female with this genetic condition. Dermatosis can also predispose children to skin infections.

Mild musculoskeletal defects may cause little functional impairment. Complete limb aplasia or severe hypoplasia may cause scoliosis, immobility, and poor dexterity.

CHILD syndrome cardiac anomalies include septal defects, a single coronary artery, and a unilateral ventricle. Severe cardiovascular abnormalities may be fatal in the first few weeks of life. Individuals with milder cardiac involvement may have poor sports tolerance in later years.

Neurologic defects are not always present. Hearing loss, blindness, and cognitive impairment have been reported. A premature female infant born with left cerebral hypoplasia, cortical polymicrogyria, ventriculomegaly, absent corpus callosum, and dysplastic left cerebellar hemisphere from CHILD syndrome expired shortly after birth.[35]

Other visceral complications in varying degrees of severity have been reported, including unilateral lung hypoplasia, ovarian and fallopian tube agenesis, and thyroid hypoplasia. Early detection and treatment can improve patient outcomes.[36]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative care and rehabilitation depend on the surgical intervention performed and the patient's age. For example, young patients who had surgery for neurologic, cardiac, and pulmonary defects may need long periods of postoperative intensive care and rehabilitation. Older patients with nonvisceral manifestations are more likely to recover and return to normal routines faster.

Consultations

The consultations vary depending on the organ systems affected. Specialists who are likely to be consulted to manage CHILD syndrome manifestations include geneticists, dermatologists, orthopedic surgeons, cardiologists, neurologists, and pulmonologists, to name a few. The condition has no known cure, though early treatment of associated defects can improve patient outcomes.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Genetic counseling is essential for the families affected by CHILD syndrome. Genetic counseling helps guardians and patients understand the condition's inheritance pattern and the risk of passing it on to future generations. Prenatal testing and counseling may be options for families considering having children. Research into potential therapies or treatments targeting the underlying genetic defect is ongoing. Currently, no specific prevention strategy is available for NSDHL mutations.

Pearls and Other Issues

The most important points to remember in managing CHILD syndrome are the following:

- CHILD syndrome is an X-linked, dominant condition with symptoms arising from NSDHL gene mutation. This genetic disorder is potentially lethal to males, so most patients who survive until late childhood, adolescence, and adulthood are females.

- On the molecular level, NSDHL gene mutation can affect the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway. Consequently, SHH signaling, which is critical to organogenesis and limb development, is disrupted.

- The condition can involve various organ systems, but the presentation is strikingly unilateral. Visceral malformations are typically ipsilateral to the skin and limb abnormalities. Most patients have right-sided manifestations. Left-sided involvement is rarer but has a poorer prognosis.

- The symptoms may be observed at birth, but late childhood presentations have also been reported. Symptoms vary in severity, and not all patients have visceral abnormalities.

- No diagnostic modality is recommended explicitly for CHILD syndrome. NSDHL gene mutation may be identified on DNA sequencing and may prove valuable during patient and family counseling.

- The condition has no known cure, but timely management of the organ malformations can help improve patient outcomes. Various specialists may be involved in the care of patients with CHILD syndrome.

No preventive measures are available specifically for this condition.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

CHILD syndrome is best managed with a multidisciplinary approach. The interprofessional team members include the following:

- Primary care physicians or pediatricians provide initial evaluation and treatment and refer patients to specialists to co-manage multiple organ defects.

- Radiologists interpret imaging studies to aid treatment planning.

- Dermatologists, orthopedic surgeons, cardiologists, neurologists, and pulmonologists may be consulted to evaluate patients with CHILD syndrome and provide specialized treatment for various organ defects.

- Geneticists oversee specialized care and provide genetic counseling to patients and families.

- Pediatric intensivists render care to patients with severe visceral abnormalities or who have recently undergone surgery to correct visceral conditions.

- Nursing staff monitors patients' vital signs and progress, administers medications to admitted patients, coordinates care, and helps educate patients and families.

- Anesthesia specialists provide effective pain control and ensure patient safety and comfort during surgery.

- Rehabilitation teams, including physical and occupational therapists, help patients improve function while recovering from surgery.

Seamless coordination among these professionals can help improve the quality of life for patients with CHILD syndrome.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Zhuang J, Luo Q, Xie M, Chen Y, Jiang Y, Zeng S, Wang Y, Xie Y, Chen C. Etiological identification of recurrent male fatality due to a novel NSDHL gene mutation using trio whole-exome sequencing: A rare case report and literature review. Molecular genetics & genomic medicine. 2023 Mar:11(3):e2121. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.2121. Epub 2022 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 36504312]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTan EC, Chia SY, Rafi'ee K, Lee SX, Kwek ABE, Tan SH, Ng VWL, Wei H, Koo S, Koh AL, Koh MJ. A novel NSDHL variant in CHILD syndrome with gastrointestinal manifestations and localized skin involvement. Molecular genetics & genomic medicine. 2022 Jan:10(1):e1848. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.1848. Epub 2021 Dec 26 [PubMed PMID: 34957706]

Tang MM, Tan WC, Surana U, Leong KF, Pramano ZAD. CHILD syndrome in a Malaysian adult with identification of a novel heterozygous missense mutation NSDHL c.602A}G. International journal of dermatology. 2021 Apr:60(4):e154-e156. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15296. Epub 2020 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 33169834]

Bittar M, Happle R. CHILD syndrome avant la lettre. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2004 Feb:50(2 Suppl):S34-7 [PubMed PMID: 14726863]

Happle R, Koch H, Lenz W. The CHILD syndrome. Congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform erythroderma and limb defects. European journal of pediatrics. 1980 Jun:134(1):27-33 [PubMed PMID: 7408908]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHettiarachchi D, Panchal H, Lai PS, Dissanayake VHW. Novel variant in NSDHL gene associated with CHILD syndrome and syndactyly- a case report. BMC medical genetics. 2020 Aug 20:21(1):164. doi: 10.1186/s12881-020-01094-y. Epub 2020 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 32819291]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFink-Puches R, Soyer HP, Pierer G, Kerl H, Happle R. Systematized inflammatory epidermal nevus with symmetrical involvement: an unusual case of CHILD syndrome? Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1997 May:36(5 Pt 2):823-6 [PubMed PMID: 9146558]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEstapé A, Josifova D, Rampling D, Glover M, Kinsler VA. Congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform naevus and limb defects (CHILD) syndrome without hemidysplasia. The British journal of dermatology. 2015 Jul:173(1):304-7. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13636. Epub 2015 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 25533639]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMi XB, Luo MX, Guo LL, Zhang TD, Qiu XW. CHILD Syndrome: Case Report of a Chinese Patient and Literature Review of the NAD[P]H Steroid Dehydrogenase-Like Protein Gene Mutation. Pediatric dermatology. 2015 Nov-Dec:32(6):e277-82. doi: 10.1111/pde.12701. Epub 2015 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 26459993]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYang Z, Hartmann B, Xu Z, Ma L, Happle R, Schlipf N, Zhang LX, Xu ZG, Wang ZY, Fischer J. Large deletions in the NSDHL gene in two patients with CHILD syndrome. Acta dermato-venereologica. 2015 Nov:95(8):1007-8. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2143. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26014843]

Johnson RL, Scott MP. New players and puzzles in the Hedgehog signaling pathway. Current opinion in genetics & development. 1998 Aug:8(4):450-6 [PubMed PMID: 9729722]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHas C, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Müller D, Floeth M, Folkers E, Donnai D, Traupe H. The Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome (CDPX2) and emopamil binding protein: novel mutations, and somatic and gonadal mosaicism. Human molecular genetics. 2000 Aug 12:9(13):1951-5 [PubMed PMID: 10942423]

Fackler N, Zachary C, Kim DJ, Smith J, Sarpa HG. Not lost to follow-up: A rare case of CHILD syndrome in a boy reappears. JAAD case reports. 2018 Nov:4(10):1010-1013. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.10.001. Epub 2018 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 30456274]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePorter FD. Human malformation syndromes due to inborn errors of cholesterol synthesis. Current opinion in pediatrics. 2003 Dec:15(6):607-13 [PubMed PMID: 14631207]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBornholdt D, König A, Happle R, Leveleki L, Bittar M, Danarti R, Vahlquist A, Tilgen W, Reinhold U, Poiares Baptista A, Grosshans E, Vabres P, Niiyama S, Sasaoka K, Tanaka T, Meiss AL, Treadwell PA, Lambert D, Camacho F, Grzeschik KH. Mutational spectrum of NSDHL in CHILD syndrome. Journal of medical genetics. 2005 Feb:42(2):e17 [PubMed PMID: 15689440]

Preiksaitiene E, Caro A, Benušienė E, Oltra S, Orellana C, Morkūnienė A, Roselló MP, Kasnauskiene J, Monfort S, Kučinskas V, Mayo S, Martinez F. A novel missense mutation in the NSDHL gene identified in a Lithuanian family by targeted next-generation sequencing causes CK syndrome. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2015 Jun:167(6):1342-8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36999. Epub 2015 Apr 21 [PubMed PMID: 25900314]

Hashimoto K, Prada S, Lopez AP, Hoyos JG, Escobar M. CHILD syndrome with linear eruptions, hypopigmented bands, and verruciform xanthoma. Pediatric dermatology. 1998 Sep-Oct:15(5):360-6 [PubMed PMID: 9796585]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGregersen PA, McKay V, Walsh M, Brown E, McGillivray G, Savarirayan R. A new case of Greenberg dysplasia and literature review suggest that Greenberg dysplasia, dappled diaphyseal dysplasia, and Astley-Kendall dysplasia are allelic disorders. Molecular genetics & genomic medicine. 2020 Jun:8(6):e1173. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.1173. Epub 2020 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 32304187]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim CA, Konig A, Bertola DR, Albano LM, Gattás GJ, Bornholdt D, Leveleki L, Happle R, Grzeschik KH. CHILD syndrome caused by a deletion of exons 6-8 of the NSDHL gene. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland). 2005:211(2):155-8 [PubMed PMID: 16088165]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZeng R, Yang X, Lin L, Jiang Y. Bilateral verruciform lesions: A new CHILD syndrome presentation. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2023 May-Jun:89(3):497. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_1293_20. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36688896]

Armina S, Heiko T, Rudolf H, Judith F, Dimitra K, Peter S. Verrucous hyperkeratosis with predominant involvement of the left side of the body and concomitant onychodystrophy in a 17-year-old girl. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft = Journal of the German Society of Dermatology : JDDG. 2020 Sep:18(9):1054-1057. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14141. Epub 2020 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 32515052]

Happle R. Ptychotropism as a cutaneous feature of the CHILD syndrome. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1990 Oct:23(4 Pt 1):763-6 [PubMed PMID: 2229513]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSonderman KA, Wolf LL, Madenci AL, Beres AL. Insurance status and pediatric mortality in nonaccidental trauma. The Journal of surgical research. 2018 Nov:231():126-132. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.05.033. Epub 2018 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 30278919]

Rossi M, Hall CM, Bouvier R, Collardeau-Frachon S, Le Breton F, Bucourt M, Cordier MP, Vianey-Saban C, Parenti G, Andria G, Le Merrer M, Edery P, Offiah AC. Radiographic features of the skeleton in disorders of post-squalene cholesterol biosynthesis. Pediatric radiology. 2015 Jul:45(7):965-76. doi: 10.1007/s00247-014-3257-9. Epub 2015 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 25646736]

Porter FD, Herman GE. Malformation syndromes caused by disorders of cholesterol synthesis. Journal of lipid research. 2011 Jan:52(1):6-34. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R009548. Epub 2010 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 20929975]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBergqvist C, Abdallah B, Hasbani DJ, Abbas O, Kibbi AG, Hamie L, Kurban M, Rubeiz N. CHILD syndrome: A modified pathogenesis-targeted therapeutic approach. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2018 Mar:176(3):733-738. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38619. Epub 2018 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 29392821]

Maceda EBG, Kratz LE, Ramos VME, Abacan MAR. Novel NSDHL gene variant for congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform erythroderma and limb defects (CHILD) syndrome. BMJ case reports. 2020 Nov 2:13(11):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-236859. Epub 2020 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 33139364]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLiu T, Qian G, Wang XX, Zhang YG. CHILD syndrome: effective treatment of ichthyosiform naevus with oral and topical ketoconazole. Acta dermato-venereologica. 2015 Jan:95(1):91-2. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1859. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24696032]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKallis P, Bisbee E, Garganta C, Schoch JJ. Rapid improvement of skin lesions in CHILD syndrome with topical 5% simvastatin ointment. Pediatric dermatology. 2022 Jan:39(1):151-152. doi: 10.1111/pde.14865. Epub 2021 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 34787337]

Yu X, Chen L, Yang Z, Gu Y, Zheng W, Wu Z, Li M, Yao Z. An excellent response to topical therapy of four congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform erythroderma and limb defects syndrome patients with an increased concentration of simvastatin ointment. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2020 Jan:34(1):e8-e11. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15838. Epub 2019 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 31374135]

Sandoval KR, Machado MCR, Oliveira ZNP, Nico MMS. CHILD syndrome: successful treatment of skin lesions with topical lovastatin and cholesterol lotion. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2019 Jul 26:94(3):341-343. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198789. Epub 2019 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 31365666]