Introduction

Cheyne-Stokes respiration is a type of breathing disorder characterized by cyclical episodes of apnea and hyperventilation. Although described in the early 19th century by John Cheyne and William Stokes, this disorder has received considerable attention in the last decade due to its association with heart failure and stroke, two major causes of mortality, and morbidity in developed countries. Unlike obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which can be the cause of heart failure, Cheyne-Stokes respiration is believed to be a result of heart failure. The presence of Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with heart failure also predicts worse outcomes and increases the risk of sudden cardiac death. Despite increasing recognition and growing knowledge, Cheyne-Stokes respiration remains elusive, and patients have very limited treatment options.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

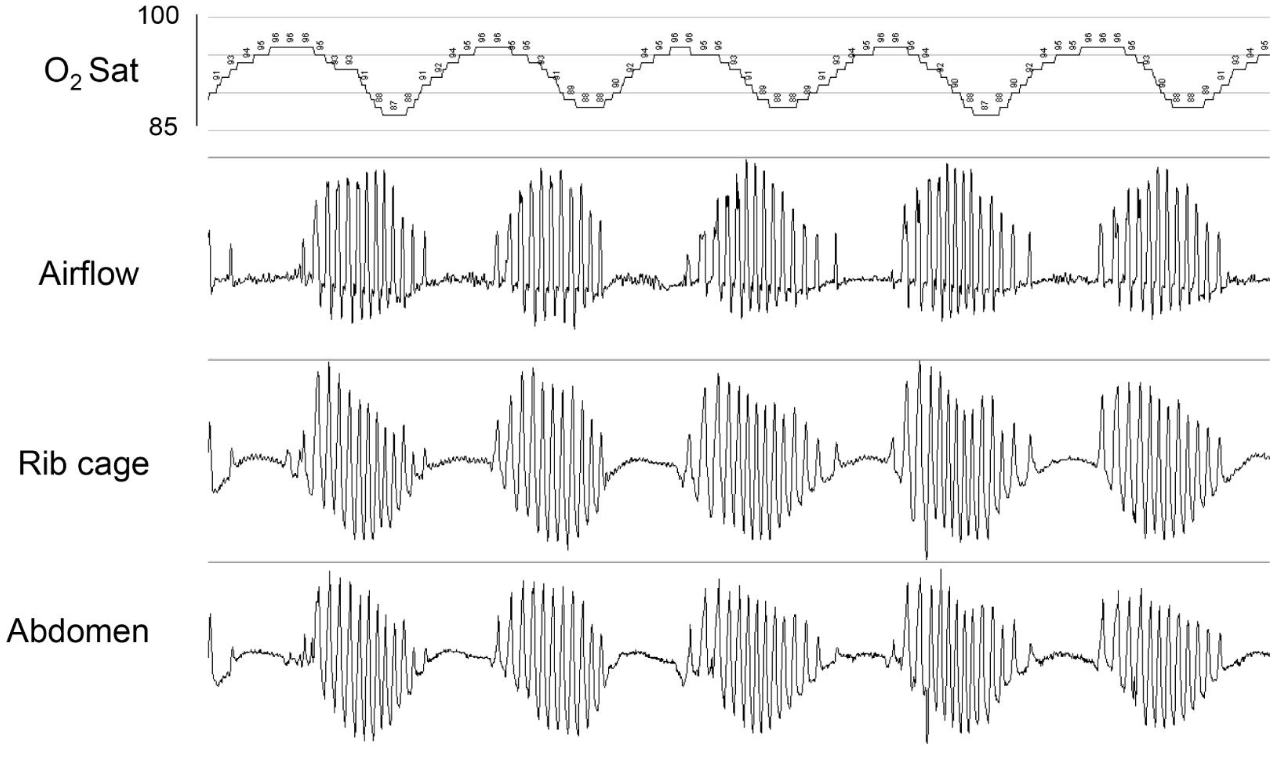

Cheyne-Stokes respiration is a specific form of periodic breathing (waxing and waning amplitude of flow or tidal volume) characterized by a crescendo-decrescendo pattern of respiration between central apneas or central hypopneas. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) recommends to score a respiratory event as Cheyne-Stokes breathing if both of the following criteria are met:

- There are episodes of at least three consecutive central apneas and/or central hypopneas separated by a crescendo and decrescendo change in breathing amplitude with a cycle length of at least 40 seconds (typically 45 to 90 seconds).

- There are five or more central apneas and/or central hypopneas per hour associated with the crescendo/decrescendo breathing pattern recorded over a minimum of two hours of monitoring.

Cheyne-Stokes respiration should be differentiated from other central sleep apneas like idiopathic central sleep apnea wherein there is no waxing and the waning pattern of ventilation. The ventilation length in patients with Cheyne-Stokes respiration is more than 40 seconds compared to less than 40 seconds in central sleep apnea. Also, the relative duration of hyperventilation is more than apnea duration in Cheyne-Stokes respiration. In central apneas, the duration of apnea is more than the duration of hyperventilation.

Cheyne-Stokes respiration is well-studied in patients with heart failure and stroke. In patients with heart failure, male gender, older age, sedentary lifestyle, diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, increased ventricular filling pressure, and more advanced cardiac remodeling are known to predispose to Cheyne-Stokes respiration. Up to 20% of patients with stroke can exhibit Cheyne-Stokes respiration.[5][6][7]

Epidemiology

The true prevalence of Cheyne-Stokes respiration in the general population is not known and is considered to be rare. Due to varied definitions and modalities of detection used, the incidence of Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with heart failure varies from 25% to 50%. This means that out of nearly 5.7 million patients with heart failure, two to three million patients are expected to have Cheyne-Stokes respiration. The incidence is reported to be more in patients with systolic heart failure compared to diastolic heart failure, and Cheyne-Stokes respiration is also more common in elderly patients.

Pathophysiology

Cheyne-Stokes respiration is initiated and maintained due to changes in the apnea threshold and the fluctuating PCO2 levels around this threshold in patients with heart failure or stroke who are at risk of unstable central respiratory control. Under normal awake conditions, ventilation is under both cortical and metabolic control. Normal respiration is maintained through the negative feedback mechanism. Peripheral and central chemoreceptors will sense PCO2 levels and trigger either positive with negative reciprocal feedback signals. Normal PCO2 levels are around 45 millimeters of mercury. The highest PCO2 levels to suppress respiration, called apnea threshold, is usually around 4 mm to 6 mm lower than the normal PCO2 levels. The sleep apnea threshold is equal or marginally lower than the aware threshold levels. The difference between these two levels is called carbon dioxide reserve. Patients with heart failure are normally tachypneic and maintain lower PCO2 levels, both awake and during sleep. Also, the carbon dioxide reserve in these patients is reduced to 1.3 mm to 3 mm of mercury lower than the resting levels.

During transition from awake to non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, cortical control of respiration is progressively diminished, and respiration is dependent on metabolic control based on PCO2 levels. During REM sleep, ventilation is predominately under central control by pontomedullary inspiratory neurons. During the N1 or N2 NREM stage, any unstable respiratory state like arousal or sudden change in sleep stage will result in hyperventilation and a decrease in PCO2 levels. If the PCO2 levels decrease below the already increased apnea threshold levels, central apnea ensues. This slow rise in PCO2 levels will stimulate chemoreceptors and will result in the hyperventilation phase. Due to unstable central control and imprecise feedback support in patients with heart failure and stroke, the PCO2 levels during hyperventilation will fall below the apnea threshold levels, resulting in apnea again. These cycles of apnea and hypercapnia continue, resulting in Cheyne-Stokes respiration.

History and Physical

The clinical features of Cheyne-Stokes respiration are similar to congestive heart failure, including dyspnea, cough, and fatigue. A patient with Cheyne-Stokes respiration with heart failure shows more lethargy and fatigue due to increased sympathetic activity because of disturbed sleep. Periodic leg movements are more common in patients with heart failure with Cheyne-Stokes respiration than patients without Cheyne-Stokes respiration.

Evaluation

Cheyne-Stokes respiration is characterized by alternating apnea and hyperventilation during sleep, mostly in the N1 and N2 sleep, and also when awake. This can be clinically observed and documented with a cyclic variation of breathing pattern with a change in saturation from 90% to 100%. Minute ventilation is not routinely monitored during sleep studies. The hyperventilation is documented by rising and falling chest excursions and the tidal volume. If the patient is on a ventilator, then the cyclical change in tidal volume and minute ventilation can be graphed together. The apnea/hyperpnea cycle is around 45 minutes to 75 minutes. This cycle is longer than other causes of central sleep apnea cycle, which typically have a cycle length of 30 to 45 minutes. Cheyne-Stokes respiration is worse in the supine position or moving from supine to lateral body position. This type of respiration can be associated with increased blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.[8]

Home sleep apnea testing with a type 3 portable monitor can be useful in identifying Cheyne-Stokes respiration and apneic events in adults with chronic heart failure.[9]

Treatment / Management

The main cornerstone of management of Cheyne-Stokes respiration is optimizing the treatment for the trigger factor, congestive heart failure (CHF), or stroke. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends that positive airway pressure should be considered for all patients with central sleep apnea. The two main modalities of noninvasive treatment for Cheyne-Stokes respiration are continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV).[10][11][12](B3)

CPAP delivers continuous positive pressure and has several mechanisms of action. The positive pressure keeps the upper airway splinted during the central apnea, leading to the stabilization of respiratory drives and improvement in oxygenation and ejection fraction. The positive pressure will also reduce the preload by reducing the venous blood flow to the right atrium and afterload by increasing the intrathoracic pressure, thereby improving the ejection fraction. In a clinical trial, CPAP therapy in patients with Cheyne-Stokes respiration showed improvement in nocturnal desaturation, Left ventricular function, and six-minute walk distance, but there was no improvement in survival.

Adaptive servo-ventilation is the newer modality of non-invasive treatment, which is effective and well-tolerated by patients. This mode of noninvasive ventilation can counteract hyperventilation during the hyperpnea phase and prevent hypoventilation during the apnea phase. It delivers constant continuous pressure and can recognize apnea or hypopnea and adjust pressure support with backup ventilation if needed to deliver preset tidal volume. During the hyperventilation phase, the pressure support is reduced, depending on the patient to prevent large tidal volume. Adaptive servo-ventilation is more effective than conventional noninvasive ventilation therapies like continuous positive airway pressure and bilevel positive airway pressure therapy and has been shown to improve the functional class, cardiac functions, exercise capacity, and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels. However, in a recent large clinical trial involving patients with systolic heart failure and Cheyne-Stokes respiration breathing, the addition of adaptive servo-ventilation to guideline-based medical therapy did not improve outcomes and increased the risk of cardiovascular death.

There are a few case reports of Theophylline being administered in fatal Cheyne-Stokes respiration with some favorable response. But this drug has to be considered with extreme precautions and is not a permanent solution.[13][14](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Cheyne Stokes respiration needs to be differentiated from abnormal respiratory patterns like:[12]

- Biot breathing

- Kussmaul respiration

- Apneustic breathing and

- Apnea

Prognosis

The presence of this pattern indicates a bad prognosis unless attended promptly. Cheyne-Stokes respiration in the upright position can be an ominous sign of cardiovascular dysregulation.[15]

Complications

If persisting for a long time, unattended, this type of breathing can lead to CO2 disturbances in the body and eventually death.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The relatives of patients should be educated to notice abnormal breathing patterns in patients with the risk of developing them. Also, they should know about positioning the patients, use of CPAP machines, and breathing exercises.

Pearls and Other Issues

The repeated interruption in breathing imposes an autonomic, chemical, mechanical, and inflammatory burden on the heart and circulation. The hypoxia during the apnea or hypopnea phase will increase sympathetic activity and myocardial damage. Hypoxia is also known to precipitate rupture of plaques, vasoconstriction of vessels, and promote dementia. Hypercapnia can cause arrhythmia and contribute to lethargy and feeling of fragmented sleep. The presence of Cheyne-Stokes respiration in a patient with heart failure is a strong independent predictor of cardiac death and hospital readmission. In clinical studies, the presence of Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with heart failure is linked to arrhythmia and arrhythmia-related death. Patients with heart failure with Cheyne-Stokes respiration are more likely to have lower ejection fraction, higher brain natriuretic peptide, and increased plasma catecholamines compared to patients without Cheyne-Stokes respiration.

Cheyne-Stokes respiration is a complex breathing disorder seen in patients with heart failure. The presence of Cheyne-Stokes respiration affects the overall prognosis of patients with heart failure. Although the exact pathophysiology of Cheyne-Stokes respiration is still not clear, the latest development in noninvasive therapy offers hope for a potential cure. Further research is needed to understand and treat this disorder precisely.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of patients with heart failure is done by an interprofessional team. One of the complications of heart failure is Cheyne-Stokes breathing. Cheyne-Stokes respiration is a type of breathing disorder characterized by cyclical episodes of apnea and hyperventilation. Although described in the early 19th century by John Cheyne and William Stokes, this disorder has received considerable attention in the last decade due to its association with heart failure and stroke, two major causes of mortality, and morbidity in developed countries. Unlike obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which can be the cause of heart failure, Cheyne-Stokes respiration is believed to be a result of heart failure. The presence of Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with heart failure also predicts worse outcomes and increases the risk of sudden cardiac death. Despite increasing recognition and growing knowledge, Cheyne-Stokes respiration remains elusive, and patients have very limited treatment options. These patients are best managed by a cardiologist, pulmonologist, heart failure specialist, intensivist, and cardiology nurses. With no ideal treatment, the prognosis for these patients is guarded.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Vargas-Ramirez L, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Franco-Reyes C, Bazurto-Zapata MA. Severe sleep apnea, Cheyne-Stokes respiration and desaturation in patients with decompensated heart failure at high altitude. Sleep science (Sao Paulo, Brazil). 2018 May-Jun:11(3):146-151. doi: 10.5935/1984-0063.20180028. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30455846]

Granitza P, Kraemer JF, Schoebel C, Penzel T, Kurths J, Wessel N. Is dynamic desaturation better than a static index to quantify the mortality risk in heart failure patients with Cheyne-Stokes respiration? Chaos (Woodbury, N.Y.). 2018 Oct:28(10):106312. doi: 10.1063/1.5039601. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30384661]

Tinoco A, Mortara DW, Hu X, Sandoval CP, Pelter MM. ECG derived Cheyne-Stokes respiration and periodic breathing are associated with cardiorespiratory arrest in intensive care unit patients. Heart & lung : the journal of critical care. 2019 Mar-Apr:48(2):114-120. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2018.09.003. Epub 2018 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 30340809]

Kim Y, Kim S, Ryu DR, Lee SY, Im KB. Factors Associated with Cheyne-Stokes Respiration in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Journal of clinical neurology (Seoul, Korea). 2018 Oct:14(4):542-548. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2018.14.4.542. Epub 2018 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 30198229]

Stellbrink C, Hansky B, Baumann P, Lawin D. [Transvenous neurostimulation in central sleep apnea associated with heart failure]. Herzschrittmachertherapie & Elektrophysiologie. 2018 Dec:29(4):377-382. doi: 10.1007/s00399-018-0591-x. Epub 2018 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 30306302]

Yamaoka-Tojo M. Is It Possible to Distinguish Patients with Terminal Stage of Heart Failure by Analyzing Their Breathing Patterns? International heart journal. 2018:59(4):674-676. doi: 10.1536/ihj.18-295. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30068834]

Pinna GD, Robbi E, Terzaghi M, Corbellini D, La Rovere MT, Maestri R. Temporal relationship between arousals and Cheyne-Stokes respiration with central sleep apnea in heart failure patients. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2018 Sep:129(9):1955-1963. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2018.05.029. Epub 2018 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 30015085]

Schreib AW, Arzt M, Heid IM, Jung B, Böger CA, Stadler S, DIACORE study group. Periodic breathing is associated with blood pressure above the recommended target in patients with type 2 diabetes. Sleep medicine: X. 2020 Dec:2():100013. doi: 10.1016/j.sleepx.2020.100013. Epub 2020 May 7 [PubMed PMID: 33870170]

Li S, Xu L, Dong X, Zhang X, Keenan BT, Han F, Bi T, Chang Y, Yu Y, Zhou B, Pack AI, Kuna ST. Home sleep apnea testing of adults with chronic heart failure. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2021 Jul 1:17(7):1453-1463. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9224. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33688828]

Wolf J, Narkiewicz K. Managing comorbid cardiovascular disease and sleep apnea with pharmacotherapy. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2018 Jun:19(9):961-969. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2018.1476489. Epub 2018 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 29792524]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDrager LF, McEvoy RD, Barbe F, Lorenzi-Filho G, Redline S, INCOSACT Initiative (International Collaboration of Sleep Apnea Cardiovascular Trialists). Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease: Lessons From Recent Trials and Need for Team Science. Circulation. 2017 Nov 7:136(19):1840-1850. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029400. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29109195]

Whited L, Graham DD. Abnormal Respirations. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262235]

Wolf J, Świerblewska E, Jasiel-Wojculewicz H, Gockowski K, Wyrzykowski B, Somers VK, Narkiewicz K. Theophylline therapy for Cheyne-Stokes respiration during sleep in a 41-year-old man with refractory arterial hypertension. Chest. 2014 Jul:146(1):e8-e10. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2897. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25010981]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePesek CA, Cooley R, Narkiewicz K, Dyken M, Weintraub NL, Somers VK. Theophylline therapy for near-fatal Cheyne-Stokes respiration. A case report. Annals of internal medicine. 1999 Mar 2:130(5):427-30 [PubMed PMID: 10068417]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFudim M, Soloveva A. Upright Cheyne-Stokes Respiration in Heart Failure: An Ominous Sign of Cardiovascular Dysregulation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2020 Oct 27:76(17):2038-2039. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.089. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33092740]