Introduction

The cerebellum is a vital component in the human brain as it plays a role in motor movement regulation and balance control. The cerebellum coordinates gait and maintains posture, controls muscle tone and voluntary muscle activity but is unable to initiate muscle contraction. Damage to this area in humans results in a loss in the ability to control fine movements, maintain posture, and motor learning.[1][2][3]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

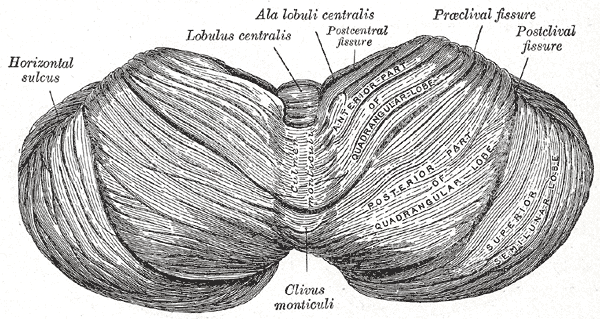

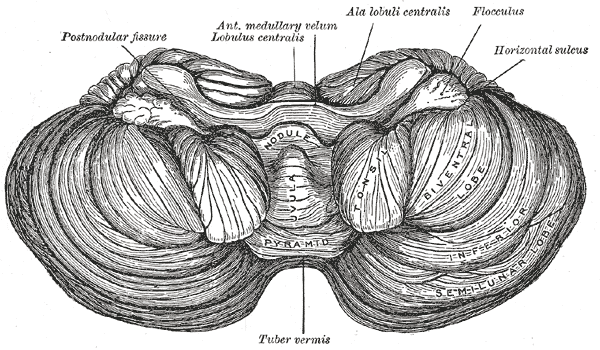

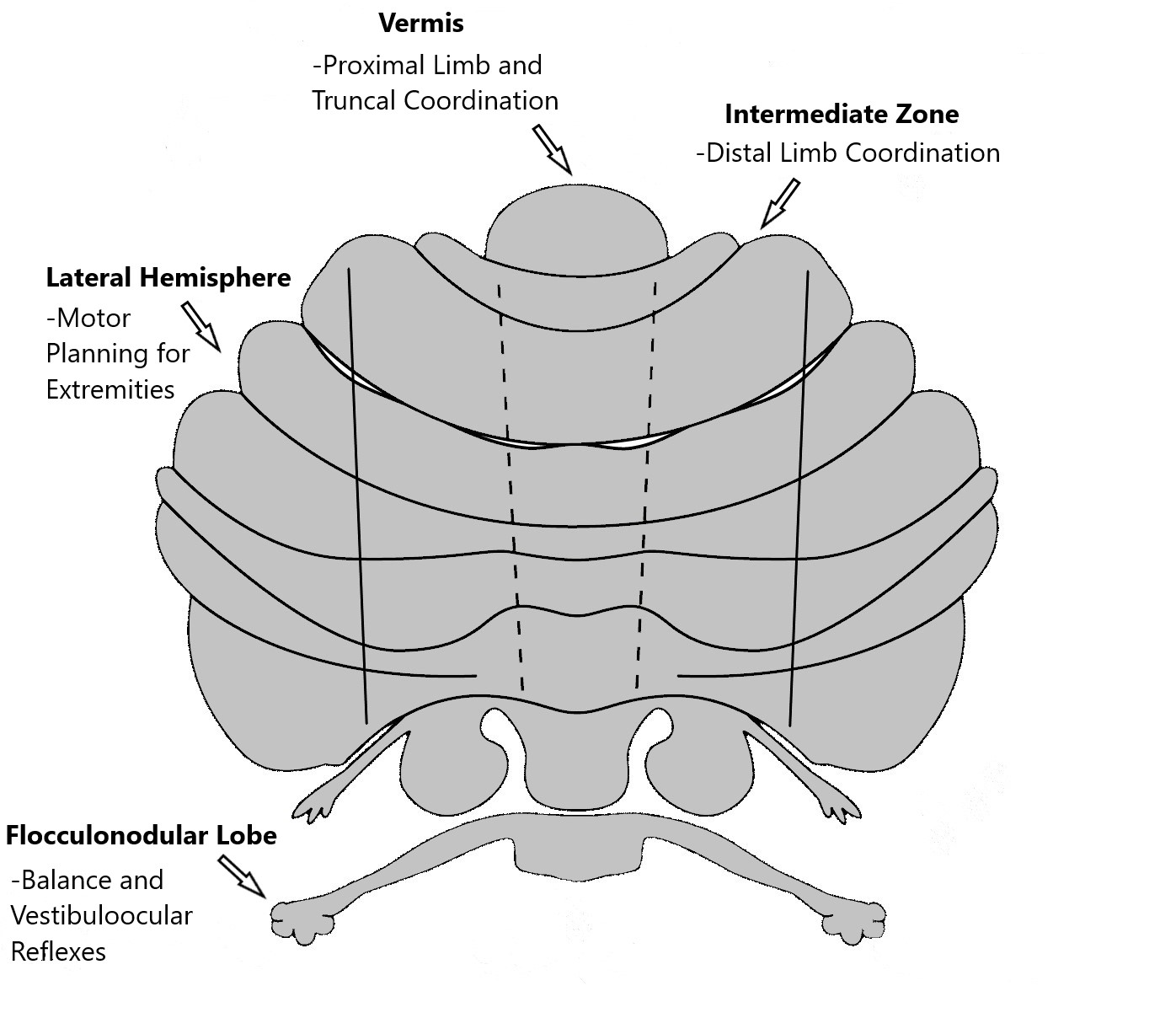

The cerebellum, which is the largest part of the hindbrain, is located in the posterior cranial fossa, behind the fourth ventricle, the pons, and the medulla oblongata. Tentorium cerebelli, an extension of the dura matter, separates the cerebellum from the cerebrum. It is composed of two hemispheres joined by the vermis and is sub-divided into three lobes – anterior, posterior, and flocculonodular, which are separated by two transverse fissures. The V-shaped primary fissure separates the anterior and posterior lobe, while the posterolateral fissure separates the posterior and flocculonodular lobes. A deep horizontal fissure found within the posterior lobe separates the superior and inferior surfaces of the cerebellum. The cerebellum is neuron-rich, containing 80% of the brain’s neurons organized in a dense cellular layer.[1][4]

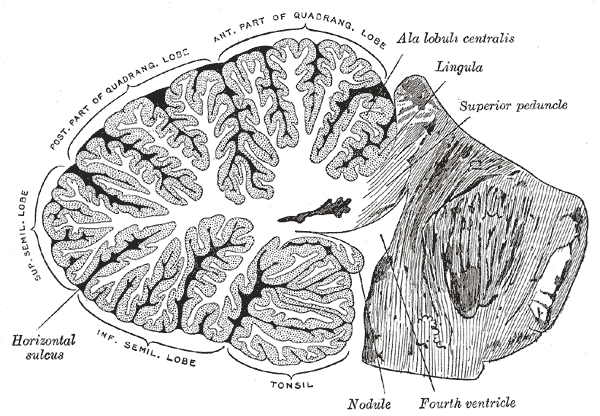

The cerebellar cortex is a sheet-like structure, made of a single sheet less than 1mm thick, and accordion-like folds fused at the midline (Essen 2018). Each fold is composed of an inner white matter core that is covered by gray matter. The gray matter of the cortex divides into three layers: an external - the molecular layer; a middle - the Purkinje cell layer; and an internal - the granular layer. The molecular layer contains two types of neurons: the outer stellate cell and the inner basket cell.[4][5]

The Purkinje layer consists of Purkinje cells, which are large Golgi type I neurons. Their dendrites reach the molecular layer and have multiple branches. The axons are long, pass through the granular layer, enter the white matter, acquire a myelin sheath, and terminate in the intracerebellar nuclei. Their collateral branches make synaptic contacts with the basket and stellate cells of the granular layer. Climbing and mossy fibers provide the primary input to the cerebellar cortex. Mossy fibers use glutamate, while the climbing fibers use aspartate as their main excitatory neurotransmitter to provide excitatory signals to the Purkinje cells. The climbing fibers are named so because they travel in the cortex like vine branches on a tree. They represent the terminal ending of the olivocerebellar tracts. The mossy fibers are the terminal branches of all other cerebellar afferent tracts. Each mossy fiber may stimulate thousands of Purkinje cells via multiple branching.[4][6]

Function: The cortex of the vermis coordinates the movements of the trunk, including the neck, shoulders, thorax, abdomen, and hips. Control of the distal extremity muscles is by the intermediate zone of the cerebellar hemispheres, located adjacent to the vermis. The remaining lateral area of each cerebellar hemisphere provides the planning of sequential movements of the entire body along with involvement in the conscious assessment of movement errors.[3][7]

Nuclei: The cerebellum consists of an outer layer of highly convoluted gray matter (cerebellar cortex) surrounding a highly branched body of white matter known as the arbor vitae (Latin for “tree of life”), which in turn surrounds the 3 pairs of deep cerebellar nuclei embedded in the central cerebellar white matter (corpus medullaris). From medial to lateral, the deep nuclei are the fastigial, interposed (consisting of globose and emboliform nuclei), and dentate nuclei, which is the largest nuclei.[1] Fibers from the dentate, emboliform, and globose nuclei leave the cerebellum through the superior cerebellar peduncle. Fibers from the fastigial nucleus exit through the inferior cerebellar peduncle.[1][8]

Embryology

The cerebellum develops from the hindbrain vesicle that gives rise to the posterior part of the alar plates of the metencephalon. The cerebellar hemisphere and vermis form by the 12th week. Accordion-like folds gradually start developing from about the fourth month. Neurons of cerebellar cortex form by the neuroblast derived from the matrix cells in the ventricular zone. Other neuroblasts from the ventricular surface differentiate into cerebellar nuclei, which axons grow towards the mesencephalon (midbrain) and create the superior cerebellar peduncle. Later, projections of the axons of the corticopontine and the pontocerebellar fibers will develop the middle cerebellar peduncle and connect the cerebral cortex with the cerebellum. The inferior cerebellar peduncle will form mainly by the growth of sensory axons from the spinal cord, the olivary and vestibular nuclei.[9]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The cerebellum receives vascular supply from three main arteries that originate from the vertebrobasilar anterior system: the superior cerebellar artery (SCA), the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA), and the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA).

The SCA branching varies based on embryology; it can branch either from the junction point of the basilar artery and posterior cerebral artery and pass below the oculomotor nerve, or directly from the posterior cerebral artery and pass above the oculomotor nerve. In the majority of subjects, the SCA encircles the brainstem below the oculomotor nerve and above the trigeminal nerve. The SCA splits into two branches: medial and lateral. The medial branch of the SCA further splits into two branches; one supplies the mesencephalon and inferior and superior colliculi while the second supplies the superior portion of the vermis and the superomedial cerebellar cortex. The lateral branch of the SCA supplies the superolateral cerebellar cortex. Blood vessels have deeper penetration in the vermis that makes it more echogenic on fetal ultrasound.[10][11]

The AICA branches off the basilar trunk in almost all subjects. It passes the abducens nerve and meets with the facial and vestibulocochlear nerves at the cerebellopontine angle. It then divides into two branches: one supplies the anterior inferior cerebellum while the other supplies the flocculus, choroid plexus, and the middle cerebellar peduncle.[10][11]

PICA is the largest vertebral artery branch. It passes between the cerebellum and the medulla and supplies the cerebellar nuclei, inferior surface of the vermis, and the undersurface area of the cerebellar hemisphere. Medulla oblongata and the choroid plexus of the fourth ventricle are supplied by PICA, which may give rise to posterior spinal arteries in some anatomical variations. The cerebellum is drained by veins that empty into the great cerebral vein or adjacent venous sinuses.[10]

Nerves

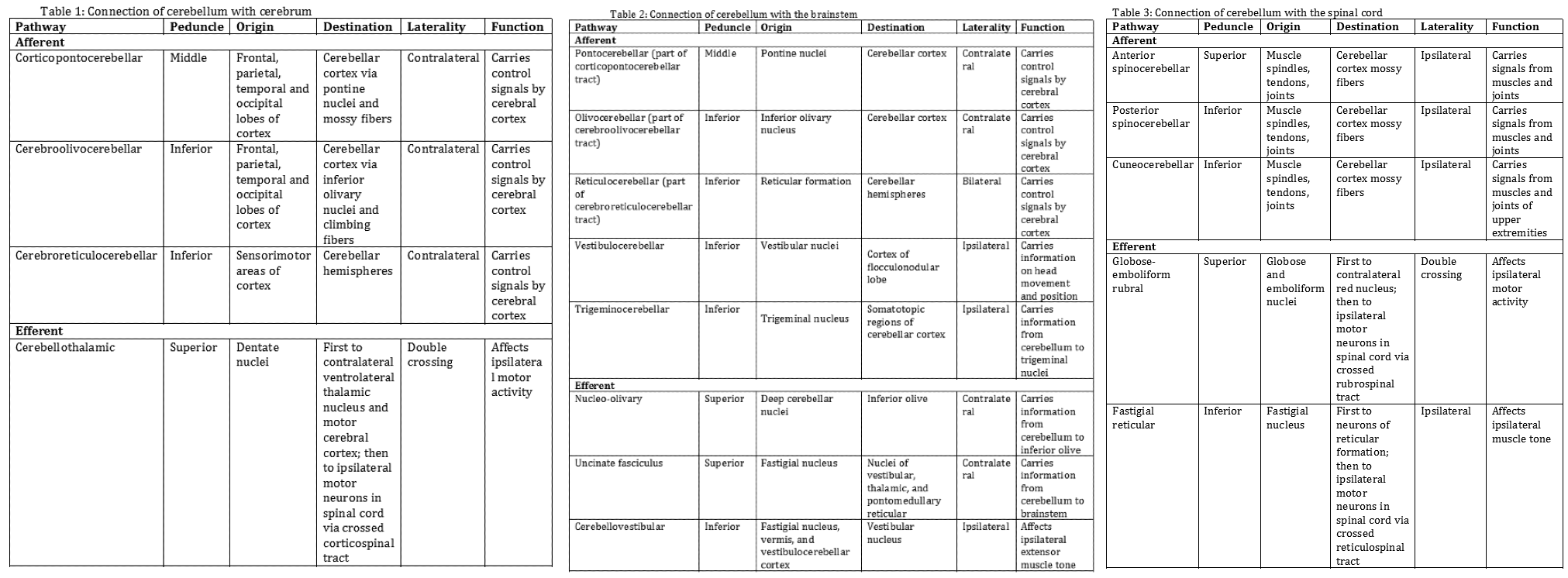

The cerebellum attaches to the brainstem by three groups of nerve fibers called the superior, middle, and inferior cerebellar peduncles, through which efferent and afferent fibers pass to connect with the rest of the nervous system. The following tables summarize how the cerebellum connects with the cerebrum (Table 1), the brainstem (Table 2), and the spinal cord (Table 3).[1][3]

- Table 1: Connection of cerebellum with the cerebrum

- Table 2: Connection of cerebellum with the brainstem

- Table 3: Connection of cerebellum with the spinal cord

Surgical Considerations

Cerebellum and its nuclei are eloquent parts of the brain and maximum effort must be put to avoid damage to these areas during surgeries in and around these structures.

Clinical Significance

The cerebellum receives afferent information about voluntary muscle movements from the cerebral cortex and from the muscles, tendons, and joints. It also receives information concerning balance from the vestibular nuclei. Each cerebellar hemisphere controls the same side of the body, thus if damaged the symptoms will occur ipsilaterally. Several signs and symptoms arise as a consequence of cerebellar dysfunction: During hypotonia, the muscles lose resistance to palpation due to diminished influence of the cerebellum on gamma motor neurons. The patient walks with a broad-based gait and leans toward the affected side. Disturbances of voluntary movements, called ataxia, involve tremors with fine movements, such as writing or buttoning the clothes. Finger to nose test is performed to examine the coordination of the muscle movements. When a patient is asked to touch the tip of the nose with the index finger, the movements are not properly coordinated, and tremor is observed at the end of the movement, called intention tremor. A similar test can be performed on the lower limbs by asking the patient to place the heel of one foot against the shin of the opposite leg. Ataxia of ocular muscles results in nystagmus, a rhythmical oscillation of the eyes. To provoke nystagmus, the patient should rotate eyes horizontally. Similarly, ataxia of the larynx muscles results in dysarthria. Speech is slurred and syllables are separated from one another. Dysdiadochokinesia is the lack of ability to perform rapidly alternating movements. One can ask the patient to quickly supinate and pronate both forearms simultaneously. Movements will be slow and incomplete on the side of the cerebellar lesion.[12][13][14]

Cerebellar syndromes involve vermis and hemispheres. In vermis syndrome, muscle incoordination involves the head and trunk. Patients cannot maintain a straight posture and may fall. The most common cause of vermis syndrome is a medulloblastoma of the vermis in children. The cerebellar syndrome involves the incoordination of muscles of the limbs unilateral to the hemisphere lesion. Dysarthria and nystagmus are also common findings. Disorders of the lateral part of the cerebellar hemispheres produce delays in initiating movements. The most common cause of cerebellar dysfunction is alcohol poisoning, but also trauma, multiple sclerosis, tumors, thrombosis of the cerebellar arteries may occur.[12][14]

Occlusion of PICA cause Wallenberg syndrome, which includes the following signs and symptoms: dysphagia and dysarthria resulting from paralysis of the ipsilateral palatal and laryngeal muscles; analgesia of the ipsilateral side of the face; vertigo, nausea, vomiting, and nystagmus; ipsilateral Horner syndrome; ipsilateral limb ataxia and contralateral loss of sensations of pain and temperature.[14]

Some data indicate that cerebellum dysfunction may correlate with disorders like autism and schizophrenia.[15]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Roostaei T, Nazeri A, Sahraian MA, Minagar A. The human cerebellum: a review of physiologic neuroanatomy. Neurologic clinics. 2014 Nov:32(4):859-69. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2014.07.013. Epub 2014 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 25439284]

Witter L, De Zeeuw CI. Regional functionality of the cerebellum. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2015 Aug:33():150-5. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2015.03.017. Epub 2015 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 25884963]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceManto M, Bower JM, Conforto AB, Delgado-García JM, da Guarda SN, Gerwig M, Habas C, Hagura N, Ivry RB, Mariën P, Molinari M, Naito E, Nowak DA, Oulad Ben Taib N, Pelisson D, Tesche CD, Tilikete C, Timmann D. Consensus paper: roles of the cerebellum in motor control--the diversity of ideas on cerebellar involvement in movement. Cerebellum (London, England). 2012 Jun:11(2):457-87. doi: 10.1007/s12311-011-0331-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22161499]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVan Essen DC, Donahue CJ, Glasser MF. Development and Evolution of Cerebral and Cerebellar Cortex. Brain, behavior and evolution. 2018:91(3):158-169. doi: 10.1159/000489943. Epub 2018 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 30099464]

Hawkes R. The Ferdinando Rossi Memorial Lecture: Zones and Stripes-Pattern Formation in the Cerebellum. Cerebellum (London, England). 2018 Feb:17(1):12-16. doi: 10.1007/s12311-017-0887-0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28965328]

Yang Y, Lisberger SG. Purkinje-cell plasticity and cerebellar motor learning are graded by complex-spike duration. Nature. 2014 Jun 26:510(7506):529-32. doi: 10.1038/nature13282. Epub 2014 May 11 [PubMed PMID: 24814344]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuell X, Schmahmann JD, Gabrieli J, Ghosh SS. Functional gradients of the cerebellum. eLife. 2018 Aug 14:7():. doi: 10.7554/eLife.36652. Epub 2018 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 30106371]

Akakin A, Peris-Celda M, Kilic T, Seker A, Gutierrez-Martin A, Rhoton A Jr. The dentate nucleus and its projection system in the human cerebellum: the dentate nucleus microsurgical anatomical study. Neurosurgery. 2014 Apr:74(4):401-24; discussion 424-5. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000293. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24448179]

Haldipur P, Dang D, Millen KJ. Embryology. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2018:154():29-44. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63956-1.00002-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29903446]

Delion M, Dinomais M, Mercier P. Arteries and Veins of the Cerebellum. Cerebellum (London, England). 2017 Dec:16(5-6):880-912. doi: 10.1007/s12311-016-0828-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27766499]

Matsushima K, Yagmurlu K, Kohno M, Rhoton AL Jr. Anatomy and approaches along the cerebellar-brainstem fissures. Journal of neurosurgery. 2016 Jan:124(1):248-63. doi: 10.3171/2015.2.JNS142707. Epub 2015 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 26274986]

Marsden JF. Cerebellar ataxia. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2018:159():261-281. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63916-5.00017-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30482319]

Manto M. Cerebellar motor syndrome from children to the elderly. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2018:154():151-166. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63956-1.00009-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29903437]

Javalkar V, Khan M, Davis DE. Clinical manifestations of cerebellar disease. Neurologic clinics. 2014 Nov:32(4):871-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2014.07.012. Epub 2014 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 25439285]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBaumann O, Borra RJ, Bower JM, Cullen KE, Habas C, Ivry RB, Leggio M, Mattingley JB, Molinari M, Moulton EA, Paulin MG, Pavlova MA, Schmahmann JD, Sokolov AA. Consensus paper: the role of the cerebellum in perceptual processes. Cerebellum (London, England). 2015 Apr:14(2):197-220. doi: 10.1007/s12311-014-0627-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25479821]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence