Introduction

A case-control study is a type of observational study commonly used to look at factors associated with diseases or outcomes.[1] The case-control study starts with a group of cases, which are the individuals who have the outcome of interest. The researcher then tries to construct a second group of individuals called the controls, who are similar to the case individuals but do not have the outcome of interest. The researcher then looks at historical factors to identify if some exposure(s) is/are found more commonly in the cases than the controls. If the exposure is found more commonly in the cases than in the controls, the researcher can hypothesize that the exposure may be linked to the outcome of interest.

For example, a researcher may want to look at the rare cancer Kaposi's sarcoma. The researcher would find a group of individuals with Kaposi's sarcoma (the cases) and compare them to a group of patients who are similar to the cases in most ways but do not have Kaposi's sarcoma (controls). The researcher could then ask about various exposures to see if any exposure is more common in those with Kaposi's sarcoma (the cases) than those without Kaposi's sarcoma (the controls). The researcher might find that those with Kaposi's sarcoma are more likely to have HIV, and thus conclude that HIV may be a risk factor for the development of Kaposi's sarcoma.

There are many advantages to case-control studies. First, the case-control approach allows for the study of rare diseases. If a disease occurs very infrequently, one would have to follow a large group of people for a long period of time to accrue enough incident cases to study. Such use of resources may be impractical, so a case-control study can be useful for identifying current cases and evaluating historical associated factors. For example, if a disease developed in 1 in 1000 people per year (0.001/year) then in ten years one would expect about 10 cases of a disease to exist in a group of 1000 people. If the disease is much rarer, say 1 in 1,000,0000 per year (0.0000001/year) this would require either having to follow 1,000,0000 people for ten years or 1000 people for 1000 years to accrue ten total cases. As it may be impractical to follow 1,000,000 for ten years or to wait 1000 years for recruitment, a case-control study allows for a more feasible approach.

Second, the case-control study design makes it possible to look at multiple risk factors at once. In the example above about Kaposi's sarcoma, the researcher could ask both the cases and controls about exposures to HIV, asbestos, smoking, lead, sunburns, aniline dye, alcohol, herpes, human papillomavirus, or any number of possible exposures to identify those most likely associated with Kaposi's sarcoma.

Case-control studies can also be very helpful when disease outbreaks occur, and potential links and exposures need to be identified. This study mechanism can be commonly seen in food-related disease outbreaks associated with contaminated products, or when rare diseases start to increase in frequency, as has been seen with measles in recent years.

Because of these advantages, case-control studies are commonly used as one of the first studies to build evidence of an association between exposure and an event or disease.

In a case-control study, the investigator can include unequal numbers of cases with controls such as 2:1 or 4:1 to increase the power of the study.

The most commonly cited disadvantage in case-control studies is the potential for recall bias.[2] Recall bias in a case-control study is the increased likelihood that those with the outcome will recall and report exposures compared to those without the outcome. In other words, even if both groups had exactly the same exposures, the participants in the cases group may report the exposure more often than the controls do. Recall bias may lead to concluding that there are associations between exposure and disease that do not, in fact, exist. It is due to subjects' imperfect memories of past exposures. If people with Kaposi's sarcoma are asked about exposure and history (e.g., HIV, asbestos, smoking, lead, sunburn, aniline dye, alcohol, herpes, human papillomavirus), the individuals with the disease are more likely to think harder about these exposures and recall having some of the exposures that the healthy controls.

Case-control studies, due to their typically retrospective nature, can be used to establish a correlation between exposures and outcomes, but cannot establish causation. These studies simply attempt to find correlations between past events and the current state.

When designing a case-control study, the researcher must find an appropriate control group. Ideally, the case group (those with the outcome) and the control group (those without the outcome) will have almost the same characteristics, such as age, gender, overall health status, and other factors. The two groups should have similar histories and live in similar environments. If, for example, our cases of Kaposi's sarcoma came from across the country but our controls were only chosen from a small community in northern latitudes where people rarely go outside or get sunburns, asking about sunburn may not be a valid exposure to investigate. Similarly, if all of the cases of Kaposi's sarcoma were found to come from a small community outside a battery factory with high levels of lead in the environment, then controls from across the country with minimal lead exposure would not provide an appropriate control group. The investigator must put a great deal of effort into creating a proper control group to bolster the strength of the case-control study as well as enhance their ability to find true and valid potential correlations between exposures and disease states.

Similarly, the researcher must recognize the potential for failing to identify confounding variables or exposures, introducing the possibility of confounding bias, which occurs when a variable that is not being accounted for that has a relationship with both the exposure and outcome. This can cause us to accidentally be studying something we are not accounting for but that may be systematically different between the groups.

Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Function

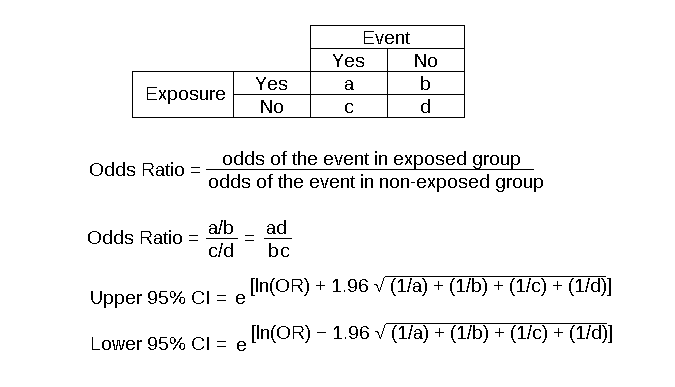

The major method for analyzing results in case-control studies is the odds ratio (OR). The odds ratio is the odds of having a disease (or outcome) with the exposure versus the odds of having the disease without the exposure. The most straightforward way to calculate the odds ratio is with a 2 by 2 table divided by exposure and disease status (see below). Mathematically, we can write the odds ratio as follows. See Figure. Case-Control Studies Odds Ratio.

Odds ratio = [(Number exposed with disease)/(Number exposed without disease) ]/[(Number not exposed to disease)/(Number not exposed without disease) ]

This can be rewritten as:

Odds ratio = [ (Number exposed with disease) x (Number not exposed without disease) ] / [ (Number exposed without disease ) x (Number not exposed with disease) ]

The odds ratio tells us how strongly the exposure is related to the disease state. An odds ratio of greater than one implies the disease is more likely with exposure. An odds ratio of less than one implies the disease is less likely with exposure and thus the exposure may be protective. For example, a patient with a prior heart attack taking a daily aspirin has a decreased odds of having another heart attack (odds ratio less than one). An odds ratio of one implies there is no relation between the exposure and the disease process.

Odds ratios are often confused with Relative Risk (RR), which is a measure of the probability of the disease or outcome in the exposed vs unexposed groups. For very rare conditions, the OR and RR may be very similar, but they are measuring different aspects of the association between outcome and exposure. The OR is used in case-control studies because RR cannot be estimated; whereas in randomized clinical trials, a direct measurement of the development of events in the exposed and unexposed groups can be seen. RR is also used to compare risk in other prospective study designs.

Issues of Concern

The main issues of concern with a case-control study are recall bias, its retrospective nature, the need for a careful collection of measured variables, and the selection of an appropriate control group.[3] These are discussed above in the disadvantages section.

Clinical Significance

A case-control study is a good tool for exploring risk factors for rare diseases or when other study types are not feasible. Many times an investigator will hypothesize a list of possible risk factors for a disease process and will then use a case-control study to see if there are any possible associations between the risk factors and the disease process. The investigator can then use the data from the case-control study to focus on a few of the most likely causative factors and develop additional hypotheses or questions. Then through further exploration, often using other study types (such as cohort studies or randomized clinical studies) the researcher may be able to develop further support for the evidence of the possible association between the exposure and the outcome.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Case-control studies are prevalent in all fields of medicine from nursing and pharmacy to use in public health and surgical patients. Case-control studies are important for each member of the health care team to not only understand their common occurrence in research but because each part of the health care team has parts to contribute to such studies. One of the most important things each party provides is helping identify correct controls for the cases. Matching the controls across a spectrum of factors outside of the elements of interest take input from nurses, pharmacists, social workers, physicians, demographers, and more. Failure for adequate selection of controls can lead to invalid study conclusions and invalidate the entire study.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Setia MS. Methodology Series Module 2: Case-control Studies. Indian journal of dermatology. 2016 Mar-Apr:61(2):146-51. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.177773. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27057012]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSedgwick P. Bias in observational study designs: case-control studies. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2015 Jan 30:350():h560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h560. Epub 2015 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 25636996]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGroenwold RHH, van Smeden M. Efficient Sampling in Unmatched Case-Control Studies When the Total Number of Cases and Controls Is Fixed. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.). 2017 Nov:28(6):834-837. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000710. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28682849]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence