Introduction

Breast calcifications are extremely common. It is important to be able to differentiate between benign and malignant calcifications because approximately half of all non-palpable breast cancers are associated with calcifications.[1] Proper identification of benign calcifications as such can avoid unnecessary intervention and use of finite resources.

The Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) lexicon, the standardized method of conveying mammographic findings as developed by the American College of Radiology, separates calcifications into “typically benign” and “suspicious morphology” categories. This article will discuss the typically benign calcifications. Because calcifications are most readily identifiable mammographically, as opposed to on MRI or ultrasound on which susceptibility artifact and posterior shadowing obscure the details of calcification morphology, the discussion to follow will be in the context of mammography unless otherwise stated.[2][3][4]

The standard approach to calcifications outlines the type/shape of calcification and the distribution within the breast. Skin, vascular, coarse or popcorn-like, large rod-like, round, rim, dystrophic, milk of calcium, and suture calcifications comprise the “typically benign” category. After calcifications have been identified, a description of the distribution of calcifications should be applied. Diffuse, regional, grouped, linear, and segmental are the available standard descriptors for conveying the distribution of calcifications.[2][3] Calcifications in a diffuse distribution, especially when bilateral, are almost always benign.[5][6] The remaining categories for describing distribution are associated with varying degrees of positive predictability of breast cancer, which is beyond the scope of this article.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Typically benign breast calcifications have a wide range of etiologies.

Skin calcifications localize to the skin, particularly the dermis, and result from processes such as folliculitis or inspissated material within sweat glands (figure 1A and 1B).[7]

Vascular calcifications have been associated with increasing age, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, pregnancy, and breastfeeding.[8][9] These calcifications typically have a tram-track appearance (figure 2).

Coarse or popcorn-like calcifications are associated with involuting fibroadenomas or papillomas.[10][11]

Large rod-like calcifications represent areas of ductal ectasia (figure 3A).[12]

Round calcifications (figure 2) may be seen in hemangiomas.[13]

Rim calcifications (figure 4A and 4B) may result from fat necrosis, which is a common sequela of autologous fat augmentation. Additionally, rim calcification may be seen surrounding breast implants or at the periphery of free silicone or other materials injected within the breast for breast augmentation.[4][14]

Typically benign dystrophic calcifications may represent post-traumatic changes, post-surgical changes, or an area of fat necrosis.[4][10] Dystrophic calcifications have also been associated with hyperparathyroidism.[15]

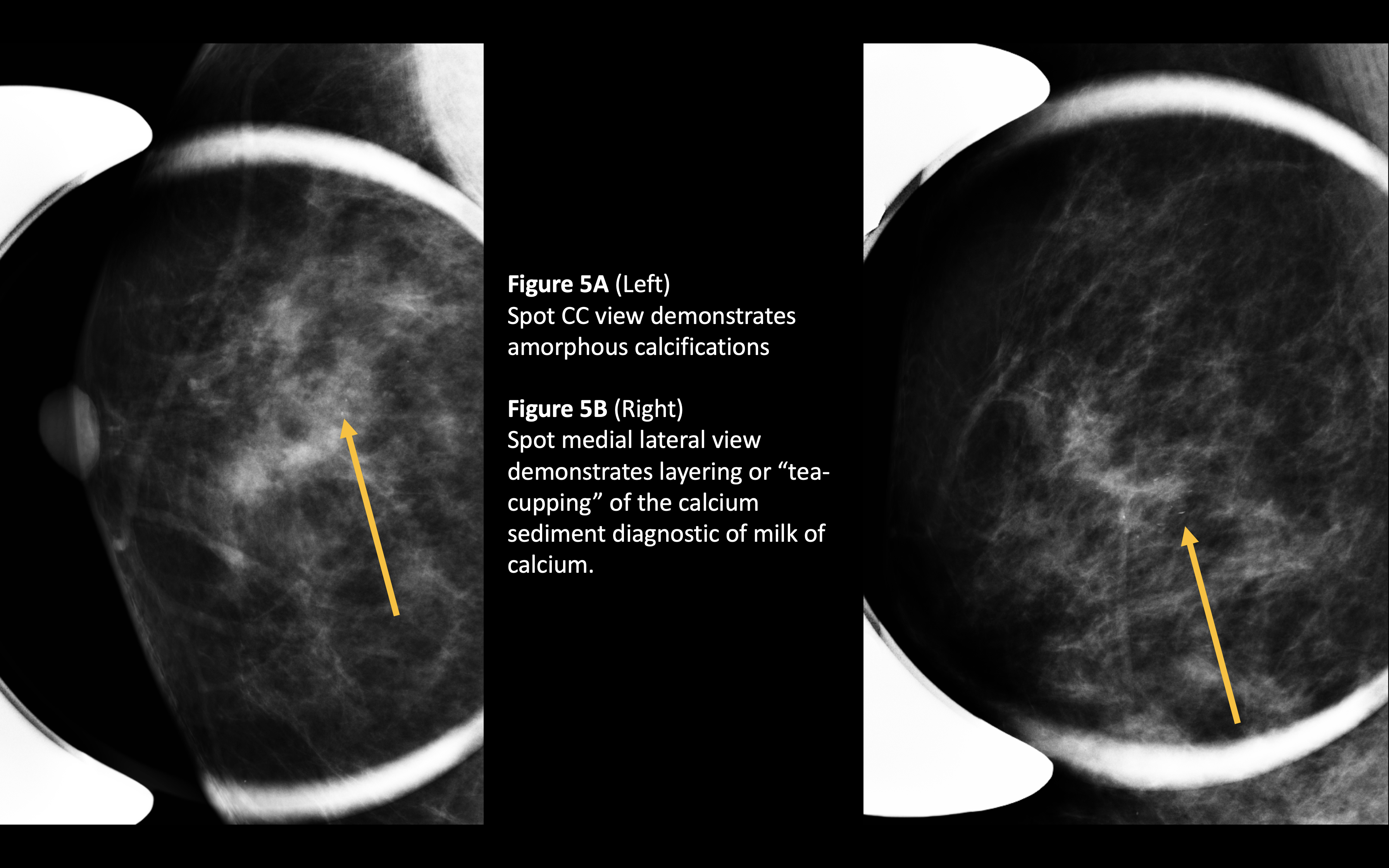

Milk-of-calcium calcifications represent calcium sediment within cysts.[11][16] These calcifications will demonstrate a layering or "tea-cupping" on a lateral view (figure 5A and 5B).

Suture calcification is a result of the formation of suture granulomas.[17]

A few additional etiologies of typically benign breast calcifications include vascular lesions, tuberculosis, and parasitic infections.[13]

Epidemiology

Approximately 50% of women have benign breast calcifications.[18]

The frequency of vascular calcifications increases with increasing age. Approximately 0.1% of women under 45 have vascular calcifications. Approximately 50% of women above 70 have vascular calcifications.[9]

Roughly 68% of women with renal disease will have benign breast calcifications of some type.[19]

Milk of calcium is present in approximately 4% to 6% of women.[20] Large rod-like calcifications are present in about 3% of women.[12]

Postoperative benign calcifications, which primarily include dystrophic, rim, and suture calcifications, are seen about 28% of the time within 6 to 12 months of surgery and/or radiation.[21]

In general, breast calcifications are rare in men.[13] There is not good data on the actual prevalence of benign breast calcification. Most data on breast calcifications in the male population is in the context of malignant/suspicious calcifications. In light of the fact that the overwhelming majority (about 99%) of lesions in the male breast are benign and because calcifications associated with male breast cancer comprises less than a third of the less than 1% of breast cancers which occur in the male population, calcifications identified within a male breast are more likely to be benign than malignant.[13][22]

Histopathology

The primary composition of breast calcifications is hydroxyapatite, which will appear dark blue on hematoxylin and eosin stains. Calcium phosphate and calcium oxalate may also comprise breast calcifications; both are colorless when stained with hematoxylin and eosin.[11]

History and Physical

Breast calcifications tend to be an effect of a patient's chief complaint or an incidental finding. However, in the case of benign calcifications large enough to palpate, a patient may present with the complaint of a palpable breast lesion. The type of calcification, in this case, is most likely to be dystrophic, rim, or suture calcification.[4][14][15] The remaining types of typically benign calcifications will usually be too small to palpate.

If rim, dystrophic, and/or suture calcifications are seen on mammography, it is appropriate to inquire about a history of trauma, infection, surgery, or radiation.

Evaluation

Mammography is the standard imaging modality for the evaluation of breast calcifications. Digital breast tomosynthesis, full-field digital mammography, and screen-film mammography are the available types. The standard and basic components of a screen film or digital mammography include cranial-caudal (CC) and medial-lateral-oblique (MLO) projections of both breasts. For tomosynthesis, the basic views are synthesized 2D CC and MLO views, as well as the tomosynthesis CC and MLO views.

Often typically benign calcifications are easily identified as benign on the standard views of screen film or digital mammography and tomosynthesis. This is because many benign calcifications are considered macrocalcifications and are larger than 2 mm.[11] Occasionally, elucidating the type of calcification requires additional views. Magnification views may be helpful if the calcifications in question are small and not well seen on tomosynthesis or on the CC and MLO views obtained in digital and screen-film mammography. If milk of calcium calcifications are suspected, a true lateral view is necessary, as the layering of calcification on the true lateral view is diagnostic of milk of calcium.[10][11][16][20] Localizing skin calcifications to the skin may require tangential views; however, skin calcifications may be evident without additional views, especially when seen within the skin on tomosynthesis.[5]

Treatment / Management

Generally, once identified as a typically benign breast calcification, no further action is required. However, the difficulty arises in the overlap between calcifications that are typically benign and those of suspicious morphology. In other words, a calcification that will evolve into a typically benign calcification may look suspicious in the beginning stages and may necessitate a biopsy for tissue sampling.[4][5][10][21] Additionally, if a patient had a large palpable benign calcification that bothered them enough to have surgically removed, that could be considered as a treatment option.

Although benign in the sense of unrelated to breast cancer, breast arterial calcifications have been associated with systemic diseases such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, or chronic kidney disease.[9] Further evaluation for such diseases may be indicated.(B2)

Differential Diagnosis

The majority of the types of typically benign calcifications are easily identified and diagnostic of the causative entity, particularly suture, vascular, rim, and popcorn-like calcifications. Milk of calcium, the initial appearance of dystrophic or coarse calcifications, and the beginning stages of fat necrosis may be indistinguishable from a suspicious type of calcification.[4][5][10] The main differential diagnoses in these cases are ductal carcinoma in situ, invasive ductal carcinoma, sclerosing adenosis, lobular neoplasia, atypical ductal hyperplasia, atypical ductal hyperplasia, pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ, atypical lobular hyperplasia, and papilloma.[11] Additionally, deodorant or other topical medications may cause artifact that simulates calcification.[11] If unable to determine a benign etiology for calcifications, a biopsy may be performed.[21] Alternatively, a short interval follow-up mammogram may be indicated.

Prognosis

Benign breast calcifications do not affect patient prognosis or outcomes. The value in identifying benign calcifications as such lies is the resultant avoidance of unnecessary intervention and the subsequent efficient use of resources.

Complications

Benign breast calcifications do not cause complications.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be reassured that breast calcifications are very common. It is important to let patients know that even if a biopsy is recommended, approximately 80% of biopsies are benign.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

In the setting of benign breast calcifications, the enhancement of healthcare outcomes is a function of reduction of unnecessary intervention and unnecessary use of finite resources. The interpreting radiologist mentions typically benign calcifications to reduce confusion in the setting of calcifications that could be misinterpreted as suspicious by the non-radiologist.

Media

References

Gajdos C, Tartter PI, Bleiweiss IJ, Hermann G, de Csepel J, Estabrook A, Rademaker AW. Mammographic appearance of nonpalpable breast cancer reflects pathologic characteristics. Annals of surgery. 2002 Feb:235(2):246-51 [PubMed PMID: 11807365]

Rao AA, Feneis J, Lalonde C, Ojeda-Fournier H. A Pictorial Review of Changes in the BI-RADS Fifth Edition. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2016 May-Jun:36(3):623-39. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150178. Epub 2016 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 27082663]

Baker JA, Kornguth PJ, Floyd CE Jr. Breast imaging reporting and data system standardized mammography lexicon: observer variability in lesion description. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 1996 Apr:166(4):773-8 [PubMed PMID: 8610547]

Venkataraman S, Hines N, Slanetz PJ. Challenges in mammography: part 2, multimodality review of breast augmentation--imaging findings and complications. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2011 Dec:197(6):W1031-45. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7216. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22109317]

Horvat JV, Keating DM, Rodrigues-Duarte H, Morris EA, Mango VL. Calcifications at Digital Breast Tomosynthesis: Imaging Features and Biopsy Techniques. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2019 Mar-Apr:39(2):307-318. doi: 10.1148/rg.2019180124. Epub 2019 Jan 25 [PubMed PMID: 30681901]

Mercado CL, Koenigsberg TC, Hamele-Bena D, Smith SJ. Calcifications associated with lactational changes of the breast: mammographic findings with histologic correlation. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2002 Sep:179(3):685-9 [PubMed PMID: 12185045]

Giess CS, Raza S, Birdwell RL. Distinguishing breast skin lesions from superficial breast parenchymal lesions: diagnostic criteria, imaging characteristics, and pitfalls. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2011 Nov-Dec:31(7):1959-72. doi: 10.1148/rg.317115116. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22084181]

Maas AH, van der Schouw YT, Beijerinck D, Deurenberg JJ, Mali WP, van der Graaf Y. Arterial calcifications seen on mammograms: cardiovascular risk factors, pregnancy, and lactation. Radiology. 2006 Jul:240(1):33-8 [PubMed PMID: 16720869]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLoberant N, Salamon V, Carmi N, Chernihovsky A. Prevalence and Degree of Breast Arterial Calcifications on Mammography: A Cross-sectional Analysis. Journal of clinical imaging science. 2013:3():36. doi: 10.4103/2156-7514.119013. Epub 2013 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 24228205]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMichaels AY, Birdwell RL, Chung CS, Frost EP, Giess CS. Assessment and Management of Challenging BI-RADS Category 3 Mammographic Lesions. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2016 Sep-Oct:36(5):1261-72. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150231. Epub 2016 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 27541437]

Demetri-Lewis A, Slanetz PJ, Eisenberg RL. Breast calcifications: the focal group. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2012 Apr:198(4):W325-43. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5732. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22451569]

Graf O, Berg WA, Sickles EA. Large rodlike calcifications at mammography: analysis of morphologic features. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2013 Feb:200(2):299-303. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9104. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23345349]

Shi AA, Georgian-Smith D, Cornell LD, Rafferty EA, Staffa M, Hughes K, Kopans DB. Radiological reasoning: male breast mass with calcifications. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2005 Dec:185(6 Suppl):S205-10 [PubMed PMID: 16304041]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEbrahim L, Morrison D, Kop A, Taylor D. Breast augmentation with an unknown substance. BMJ case reports. 2014 Jun 23:2014():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-204535. Epub 2014 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 24957586]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee KM, Lee JE, Cha ES, Chung J, Kim JH, Moon BI. Dystrophic Calcifications in the Breast from Secondary Hyperparathyroidism. Breast care (Basel, Switzerland). 2018 Mar:13(1):44-46. doi: 10.1159/000484198. Epub 2018 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 29950967]

Moy L, Slanetz PJ, Yeh ED, Moore R, Rafferty E, McCarthy KA, Hall D, Kopans DB. The pendent view: an additional projection to confirm the diagnosis of milk of calcium. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2001 Jul:177(1):173-5 [PubMed PMID: 11418421]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBrenner RJ, Pfaff JM. Mammographic features after conservation therapy for malignant breast disease: serial findings standardized by regression analysis. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 1996 Jul:167(1):171-8 [PubMed PMID: 8659366]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNyante SJ, Lee SS, Benefield TS, Hoots TN, Henderson LM. The association between mammographic calcifications and breast cancer prognostic factors in a population-based registry cohort. Cancer. 2017 Jan 1:123(2):219-227. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30281. Epub 2016 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 27683209]

Sommer G, Kopsa H, Zazgornik J, Salomonowitz E. Breast calcifications in renal hyperparathyroidism. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 1987 May:148(5):855-7 [PubMed PMID: 3554917]

Park JS, Park YM, Kim EK, Lee JH, Kim OH, Ryu JH. Carcinoma mixed within milk of calcium in a breast: a case report. Korean journal of radiology. 2008 Jul:9 Suppl(Suppl):S7-9. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2008.9.s.s7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18607132]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChansakul T, Lai KC, Slanetz PJ. The postconservation breast: part 1, Expected imaging findings. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2012 Feb:198(2):321-30. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.7298. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22268174]

Chen L, Chantra PK, Larsen LH, Barton P, Rohitopakarn M, Zhu EQ, Bassett LW. Imaging characteristics of malignant lesions of the male breast. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2006 Jul-Aug:26(4):993-1006 [PubMed PMID: 16844928]