Introduction

Multiple biliary duct hamartomas or “von Meyenburg complexes” are rare, benign liver malformations characterized by cystic dilated biliary ducts that were first discovered in 1918 by Von Meyenburg. They are usually incidentally found at autopsy or laparotomy due to the asymptomatic clinical course.[1][2][3][4] They are usually diagnosed on imaging as single or multiple small cystic nodules ranging from 0.05 cm to 1.5 cm in size. Although incidental findings can mimic metastatic liver disease as well as other clinically significant diseases, which may prompt an extensive diagnostic work-up and even surgical intervention.[5] Thus, proper diagnosis with specific imaging findings or confirmation with histological evaluation is required.[6][7]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Biliary duct hamartomas, otherwise known as Von Meyenburg complexes, are dilated cystic bile ducts, which are embryologic remnants that failed to involute during the period of embryogenesis. They are typically small (<5 mm) and present as multiple lesions scattered throughout the liver, often referred to as "a starry night."[8] They are rare, asymptomatic, and with a relatively benign disease course. They are most commonly found during laparotomy for another procedure, on imaging, or at autopsy. Etiology is unknown; however, biliary duct hamartomas are thought to develop from the smaller embryonic interlobular bile ducts, which fail to involute.[9] Several studies have found an increased frequency in cirrhotic livers due to chronic viral hepatitis or alcohol liver disease or secondary to inflammation or ischemia, which may demonstrate that these lesions can be acquired and environmental exposure can play an important role.[2][4][5] In addition, biliary duct hamartomas are more common in patients with polycystic liver and polycystic kidney disease or those with congenital hepatic fibrosis.[2]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of multiple biliary duct hamartomas ranges from 0.6% to 5.6% in adults seen at autopsy and 0.35% in needle biopsy of liver lesions for diagnosis.[3][4][10] Prevalence in children is 0.9%.[11] Although they have been observed in infants and children under two years of age, most patients are older than 35.[8] Women are affected 3 times more than males.[4] According to an autopsy study, approximately 5% of the population have bile duct hamartomas.[12]

Pathophysiology

Bile duct hamartomas are thought to arise from the abnormal development of intrahepatic bile ducts. Histologically, they are composed of inflammatory cells, bile ducts, and fibrosis. No BRAF V600E mutations have yet been identified in biliary hamartomas despite bile duct adenomas having that mutation.[13] Biliary duct hamartomas have a minor risk of malignant transformation to intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma or, less commonly, hepatocellular carcinomas.[5]

Histopathology

Macroscopically, biliary duct hamartomas appear as multiple small grey-white nodules scattered throughout both liver lobes within the subcapsular and periportal areas (see Image. Multiple Biliary Hamartoma). These lesions typically do not communicate with the biliary tree, although they can.[3][9] Microscopically, they are composed of a collection of dilated branching cystic bile ducts lined with a single layer of cuboid epithelial cells surrounded by an abundant fibro-collagenous stroma. The lesions measure about 0.1 cm to 1.5 cm each. The bile duct lumens typically contain bile-stained granular material.[2][3][10] They are thought to arise from congenital bile duct remnants that have failed to involute.[3]

History and Physical

Typically, patients are clinically asymptomatic with an unremarkable physical exam, as the diagnosis is usually incidental to laparotomy for another procedure. Rarely will patients present with fevers, jaundice, abdominal distension, and right upper quadrant or epigastric pain.[3][10][11] Abdominal pain is the most common presenting symptom among those who are symptomatic. While most physical exams are unremarkable, positive Murphy sign and right upper quadrant tenderness to palpation were prevalent.[5]

Evaluation

As a result of the incidental and usually benign nature of multiple biliary duct hamartomas, no evaluation is necessary for the diagnosis. However, while most patients will have normal lab results, some can present with mild elevations in liver function tests, specifically aspartate aminotransferase and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT). Patients should have a baseline CA 19-9 level drawn, which can be slightly elevated with multiple biliary duct hamartomas. Some patients have seen hyperbilirubinemia, hypoalbuminemia, and increased C-reactive protein.[5]

Typically these lesions are found initially on ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) done for a different reason. On ultrasound, these lesions appear as multiple hyper and hypoechoic areas within the liver with comet-tail artifacts. On CT, they appear as multiple, nodular, irregular cystic liver lesions with low attenuation and no enhancement with intravenous contrast injection. The most sensitive imaging modality is magnetic resonance imaging or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRI/MRCP), which shows multiple T1 hypointense and T2 hyperintense diffuse cystic liver lesions of variable sizes 0.1 cm to 1.5 cm that do not communicate with the biliary tree and do not enhance with intravenous gadolinium injection.[10][11][14]

The most specific finding on MRCP for biliary duct hamartomas is mural nodules, which are endocytic polypoid projections due to conjunctive septa that are isointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. The presence of mural nodules can help diagnose multiple biliary duct hamartomas with accuracy and help avoid misdiagnosis.[15] While biopsies are not necessary for diagnosis, most patients will undergo biopsies as part of the workup. A biopsy is the best diagnostic tool to rule out malignancy.[5]

Treatment / Management

Aside from the possible risk of malignant transformation, multiple biliary duct hamartomas are benign, otherwise, asymptomatic conditions with no long-term adverse outcomes, and no treatment is required.[11] However, suspicious lesions should be followed regularly with repeat imaging and possible liver biopsy for a definitive diagnosis. Any changes of the lesion on repeat imaging, warning signs, such as weight loss, or any elevations from tumor markers (CA 19-9) from baseline should warrant further workup with possible surgical resection when the diagnosis is definitive and the lesion is operable.[4][11] (B2)

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of multiple biliary duct hamartomas is usually incidental at autopsy or on radiographic imaging. However, when discovered on imaging, it is essential to determine a correct diagnosis due to its close resemblance to metastatic disease of the liver, especially in a patient with extra-hepatic malignant tumors. Typically, liver metastases are ill-defined with variable sizes on plain CT imaging with varying degrees of enhancement with IV contrast.[3] Bile duct hamartomas, on the contrary, typically do not enhance with IV contrast on CT imaging, are usually uniform, and measure 1 mm to 15 mm in size.[2]

Other differential diagnoses include bile duct adenomas, peribiliary cysts, microabscesses of the liver, intrahepatic biliary stones, and Caroli disease. Bile duct adenomas have small round tubules with small inconspicuous lumens, while bile duct hamartomas have dilated lumens with inspissated bile.[2] Peribiliary cysts are located specifically within the hepatic hilum within connective tissue along the portal vein, do not communicate with the biliary tree, and typically enlarge and compress the biliary tree over time, which is contrasted to the diffuse scattered nature of biliary duct hamartomas.[3][9]

Microabscesses of the liver are usually present as multiple round loculated hypodense lesions on CT. They are seen in patients with immunosuppression, fever, and epigastric pain, which can be differentiated from bile duct hamartomas by signs of sepsis, which are not typically seen in the latter.[3] Caroli disease is characterized by intrahepatic bile duct dilation communicating with the biliary tree, differentiated from bile duct hamartomas with MRCP by contrast enhancement with intravenous gadolinium.[3][14]

Surgical Oncology

The clinical problem posed by this benign tumor is for the surgeon or surgical oncologist who encounters such a lesion during a laparotomy for another malignant lesion. Typically, the surgeon will perform a liver biopsy for a frozen section once this lesion is encountered. It can be difficult to distinguish benign hamartomas from metastatic disease in the liver. A pathologist who receives the specimen for the frozen section and is unaware of this entity may label the lesion as metastatic carcinoma or Carolis disease. However, these lesions do not communicate with bile ducts, and no treatment is necessary.

Prognosis

Due to the asymptomatic clinical course in most and incidental findings at autopsy for patients who die of unrelated diseases, the prognosis is typically great. However, patients with malignant transformation typically have a very poor 5-year survival rate of 15% to 40%.[16] Some patients with diffuse biliary duct hamartomas often have persistently elevated liver function tests on their laboratory testing, at which point liver transplantation would be recommended.[8]

Complications

Small subsets of patients experience a malignant transformation of multiple biliary duct hamartomas to either intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (more common) or hepatocellular carcinoma. Risk factors for possible malignant transformation include long-term tobacco use, large biliary duct hamartomas (> 2 cm), and bile stasis.[17] It is essential to have periodic long-term follow-ups with these patients with a definitive diagnosis of multiple biliary duct hamartomas. Patients require a baseline CA 19-9 level, which can be slightly elevated with multiple biliary duct hamartomas. Any changes to MRI/MRCP imaging, in addition to elevations in tumor markers, warrant further evaluation with liver lesion biopsy and possible resection of lesions if operable with a definitive diagnosis.[11]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Educational materials for the patient, as well as clinicians and other healthcare personnel, should include the following:

- Complete understanding of the broad differential diagnoses for multiple biliary duct hamartomas

- Specific findings on ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging

- importance of long-term follow-up for these patients due to possible malignant transformation to help prevent adverse outcomes

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with multiple biliary duct hamartomas typically require no extensive workup, but an interprofessional healthcare team approach is recommended. This team includes clinicians, specialists (particularly a radiologist), and nursing staff. While the disease is generally benign, it has the potential for malignant transformation, so the entire team must remain vigilant, including the patients themselves. It is crucial that radiologists understand this disease and its appearance on imaging to help differentiate it from more malignant or life-threatening liver lesions. Surgeons and oncologists must be aware of this disease in the case of malignant transformation requiring liver resection and chemotherapy or radiation for treatment. It is a condition where the differential is extremely important since getting it wrong can result in either missing a more malignant disease or treating the patient inappropriately if it is not malignant. Good communication and education with the pathologist and surgeon are paramount to dealing with benign liver lesions and improving patient outcomes. Nurses can help coordinate the various clinicians and specialists on the case, ensure all team members have accurate and updated patient information, as well as counsel the patients regarding their condition and how to monitor for signs of possible malignant transformation. In this way, the interprofessional team approach to management is the most appropriate means to achieve optimal outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

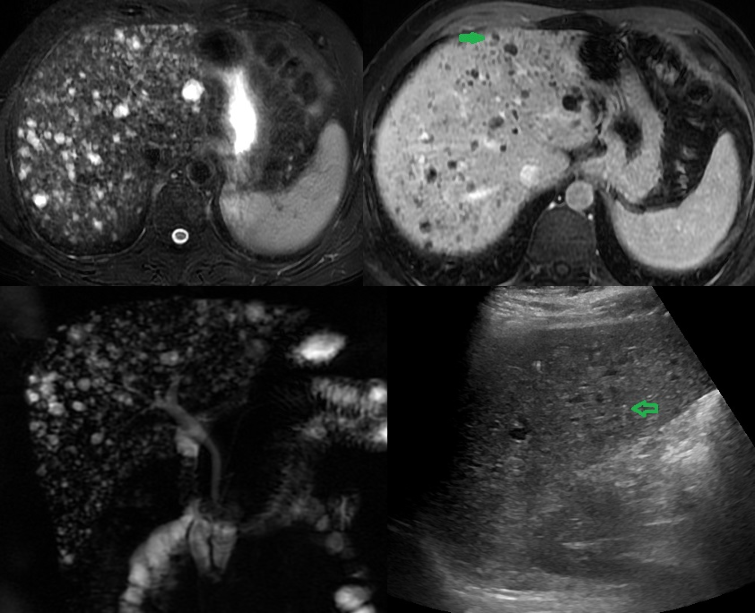

Multiple Biliary Hamartoma. Ultrasound of a 37-year-old female diagnosed with gallstones with acute cholecystitis. The incidental findings: (A) US image shows multiple hypoechoic lesions, some of them with comet-tail artifacts, raising the possibility of multiple biliary hamartoma. (B) T2-weighted MRI shows numerous cystic lesions with a signal similar to CSF. (C) Post-contrast T2 weighted MRI shows some of these lesions with enhancing mural nodule, highly specific for biliary hamartoma. (D) MRCP 3D projection image has more lesions and demonstrates no communication with normal caliber biliary duct.

Contributed by A Borhani, MD

References

Sugawara T, Shindoh J, Hoshi D, Hashimoto M. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and portal hypertension developing in a patient with multicystic biliary microhamartomas. The Malaysian journal of pathology. 2018 Dec:40(3):331-335 [PubMed PMID: 30580365]

Torbenson MS. Hamartomas and malformations of the liver. Seminars in diagnostic pathology. 2019 Jan:36(1):39-47. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2018.11.005. Epub 2018 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 30579648]

Zheng RQ, Zhang B, Kudo M, Onda H, Inoue T. Imaging findings of biliary hamartomas. World journal of gastroenterology. 2005 Oct 28:11(40):6354-9 [PubMed PMID: 16419165]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLin S,Weng Z,Xu J,Wang MF,Zhu YY,Jiang JJ, A study of multiple biliary hamartomas based on 1697 liver biopsies. European journal of gastroenterology [PubMed PMID: 23510964]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSheikh AAE, Nguyen AP, Leyba K, Javed N, Shah S, Deradke A, Cormier C, Shekhar R, Sheikh AB. Biliary Duct Hamartomas: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2022 May:14(5):e25361. doi: 10.7759/cureus.25361. Epub 2022 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 35774682]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBarboi OB, Moisii LG, Albu-Soda A, Ciortescu I, Drug V. Biliary Hamartoma. Clujul medical (1957). 2013:86(4):383-4 [PubMed PMID: 26527984]

Guo Y, Jain D, Weinreb J. Von Meyenburg Complex: Current Concepts and Imaging Misconceptions. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 2019 Nov/Dec:43(6):846-851. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000904. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31356525]

Zeng D,Wan Y, Von Meyenburg Complexes: a starry sky. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2021 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 34156678]

Pech L, Favelier S, Falcoz MT, Loffroy R, Krause D, Cercueil JP. Imaging of Von Meyenburg complexes. Diagnostic and interventional imaging. 2016 Apr:97(4):401-9. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2015.05.012. Epub 2015 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 26522945]

Jáquez-Quintana JO, Reyes-Cabello EA, Bosques-Padilla FJ. Multiple Biliary Hamartomas, The ''Von Meyenburg Complexes''. Annals of hepatology. 2017 Sep-Oct:16(5):812-813. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.2822. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28809728]

Yang XY, Zhang HB, Wu B, Li AJ, Fu XH. Surgery is the preferred treatment for bile duct hamartomas. Molecular and clinical oncology. 2017 Oct:7(4):649-653. doi: 10.3892/mco.2017.1354. Epub 2017 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 28855998]

Redston MS, Wanless IR. The hepatic von Meyenburg complex: prevalence and association with hepatic and renal cysts among 2843 autopsies [corrected]. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 1996 Mar:9(3):233-7 [PubMed PMID: 8685220]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePujals A, Bioulac-Sage P, Castain C, Charpy C, Zafrani ES, Calderaro J. BRAF V600E mutational status in bile duct adenomas and hamartomas. Histopathology. 2015 Oct:67(4):562-7. doi: 10.1111/his.12674. Epub 2015 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 25704541]

Sinakos E, Papalavrentios L, Chourmouzi D, Dimopoulou D, Drevelegas A, Akriviadis E. The clinical presentation of Von Meyenburg complexes. Hippokratia. 2011 Apr:15(2):170-3 [PubMed PMID: 22110302]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTohmé-Noun C, Cazals D, Noun R, Menassa L, Valla D, Vilgrain V. Multiple biliary hamartomas: magnetic resonance features with histopathologic correlation. European radiology. 2008 Mar:18(3):493-9 [PubMed PMID: 17934738]

Lee AJ, Chun YS. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: the AJCC/UICC 8th edition updates. Chinese clinical oncology. 2018 Oct:7(5):52. doi: 10.21037/cco.2018.07.03. Epub 2018 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 30180751]

Song JS, Lee YJ, Kim KW, Huh J, Jang SJ, Yu E. Cholangiocarcinoma arising in von Meyenburg complexes: report of four cases. Pathology international. 2008 Aug:58(8):503-12. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2008.02264.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18705771]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence