Introduction

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS) is the most common congenital overgrowth syndrome. Specifically, the condition is a human imprinting disorder caused by genetic and epigenetic changes affecting molecular regulation on chromosome 11p15.

The most notable BWS features are hemihypertrophy, macrosomia, macroglossia, and abdominal wall defects. Patients also have an increased risk of childhood cancers. However, BWS presents various signs and symptoms, making the diagnosis challenging. Early recognition in the prenatal or neonatal periods is critical for monitoring and timely treatment of complications.[1][2] BWS is named after the American pediatric pathologist John Bruce Beckwith and the German pediatrician Hans-Rudolf Wiedemann, who independently described its manifestations in 1963 and 1964, respectively.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome is complex. About 80 to 90% of patients have a known chromosome 11p15.5 anomaly affecting cell cycle progression and somatic growth control. The process starts with genetic imprinting, where only one gene copy is expressed, depending on the sex of the parent carrying the allele. Two imprinting control regions, IC1 and IC2, regulate gene expression in chromosome 11p15.

Methylation, which silences gene expression, usually occurs in the paternal allele at IC1 and the maternal allele at IC2. In an individual with BWS, the molecular defects commonly described are the following:[4]

- Loss of methylation at IC2 on the maternal allele in 50% to 60% of cases

- Paternal uniparental isodisomy of chromosome 11p15 in 20% to 25% of cases

- IC1 methylation on the maternal allele in 5 to 10% of cases

- Autosomal dominant maternal point mutations in IC2-regulated CDKN1C in 5% of sporadic cases and 40% of familial cases

- Chromosomal rearrangements, ie, duplications, translocations, deletions, or inversions, in fewer than 1% of cases

- An unknown molecular defect in 10% to 15% of cases

The diversity of clinical presentations and the complexity of genetic and epigenetic BWS mechanisms make diagnosis challenging. Genetic testing and molecular analyses are often used to confirm the diagnosis and identify specific genetic abnormalities associated with the syndrome. However, the exact cause of BWS is unidentified in many cases.

Epidemiology

The incidence of BWS is estimated to be 1 in 10,000 to 13,700 live births, likely a low estimate due to the underdiagnosis of subtle phenotypes. The condition affects all ethnic groups and has a 1:1 sex ratio. A correlation exists between BWS and assisted reproductive techniques (ART), with ART increasing BWS risk tenfold.[5][6]

History and Physical

BWS is a complex multisystem disorder with a varied clinical spectrum. History and physical findings differ by age and stage of life.

Prenatal period: Pregnancy complications when fetuses have BWS usually begin after 22 weeks of gestation and include gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes mellitus, vaginal bleeding, polyhydramnios, macrosomia, increased α-fetoprotein (AFP), and ultrasonographic findings of organomegaly. At delivery, neonates may present with prematurity, placentomegaly, or macrosomia-related complications, including cephalohematoma and brachial plexus injury. A positive family history helps diagnose BWS since approximately 15% of cases are attributed to familial transmission.

Neonatal period: Neonates with BWS may have macrosomia, whole-body hemihyplasia, limb-length discrepancy, distinctive facial features, abdominal wall defects (omphalocele, umbilical hernia, or diastasis recti), organomegaly, (liver, kidneys, spleen, pancreas, thymus, heart, and adrenal glands), renal malformations and hydronephrosis, cardiac anomalies (patent ductus arteriosus, patent foramen ovale, and congenital long QT syndrome), and hypotonia. Typical dysmorphic facies include macroglossia, prominent eyes, infraorbital creases, midfacial hypoplasia, prognathism, anterior earlobe creases, posterior helical pits, and nevus flammeus of the glabella. Cleft palate, supernumerary nipples, polydactyly, and cryptorchidism are less common. Neonatal BWS may also present with hypoglycemia from islet cell hyperplasia and hyperinsulinism.[7]

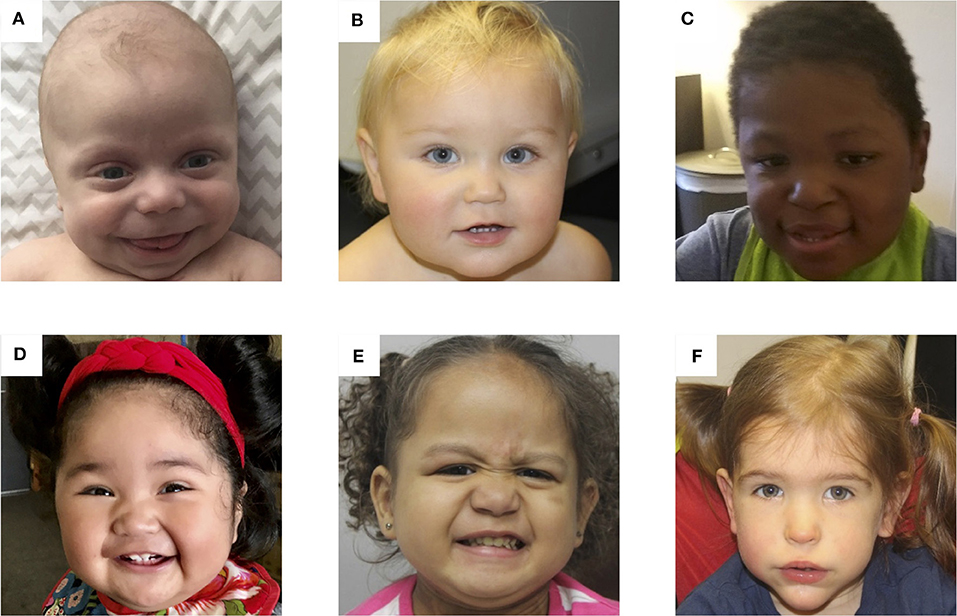

Infancy, childhood, and adolescence: Typical facial features are usually outgrown in later childhood (see Image. Photos of Patients With BWS). Height and weight often remain near the 90th percentile, while the head circumference grows closer to the mean. Development is generally unaffected unless a specific chromosome 11p15.5 duplication exists or a history of perinatal complications is present. Nephrocalcinosis, nephrolithiasis, renal cysts, and recurrent urinary tract infections may develop from infancy to adolescence. Predisposition to embryonal tumors is the most feared outcome of BWS, so long-term monitoring is recommended. The most common malignancies are Wilms tumor and hepatoblastoma, but neuroblastoma, adrenocortical carcinoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma can also occur. Tumor risk is about 5-10%, and the incidence is greatest in the first 7 years of life.[8]

Adulthood: Adult height is usually in the average range, although some studies report an increased mean adult height in the BWS population. The limb-length discrepancy can persist or worsen, predisposing to scoliosis. Fertility issues have been reported in males due to primary testicular dysfunction or cryptorchidism. Data on the female population are insufficient.[9]

Not all individuals with BWS have every characteristic feature, and the severity and combination of symptoms vary widely.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of BWS is based on clinical criteria and confirmed by molecular or cytogenetic testing. However, given the heterogeneous presentation of this disorder, no consensus exists. Most experts agree that these criteria should not replace clinical judgment. Negative diagnostic testing does not necessarily rule out a BWS clinical diagnosis.

Clinical Diagnosis

There are several published diagnostic criteria for BWS.[10][11][12][13][14][15] Recent reviews consider it acceptable to base the clinical diagnosis on major and minor findings. Three major findings or 2 major and 1 or more minor findings support a diagnosis of BWS.

Major Findings

- Abdominal wall defect, including omphalocele or umbilical hernia

- Macroglossia

- Neonatal macrosomia (birth weight greater than 90th percentile)

- Postnatal overgrowth (height/length greater than 90th percentile)

- Embryonal tumors (Wilms tumor, hepatoblastoma, adrenal tumors, neuroblastoma)

- Outer ear malformations (anterior ear creases, posterior helical pits)

- Visceromegaly

- Cytomegaly of the adrenal fetal cortex

- Hemihypertrophy

- Anomalies of the kidney and ureter (eg, medullary dysplasia, nephrocalcinosis, medullary sponge kidney, and nephromegaly)

- Positive family history of BWS

- Cleft palate

Minor Findings

- Polyhydramnios

- Enlarged placenta or placental mesenchymal dysplasia

- Thickened umbilical cord

- Prematurity

- Neonatal hypoglycemia

- Nevus flammeus of the glabella

- Distinctive facial features

- Cardiomegaly or other cardiac anomalies such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- Diastasis recti

- Polydactyly

- Supernumerary nipples

- Advanced bone age

Novel diagnostic criteria consider the predictive value of each BWS feature. In 2018, Brioude et al proposed a clinical scoring system based on cardinal and suggestive features. Cardinal features include macroglossia, omphalocele, lateralized overgrowth, bilateral Wilms tumor, hyperinsulinism, adrenal cytomegaly, or placental mesenchymal dysplasia. Suggestive features include birth weight greater than 2 standard deviations above the mean, facial nevus simplex, polyhydramnios or placentomegaly, ear creases or pits, transient hypoglycemia, embryonal tumors, nephromegaly or hepatomegaly, and umbilical hernia or diastasis recti.

Two points are assigned to each cardinal feature, and 1 point is assigned to each suggestive feature. A total score of 4 or more confirms a diagnosis of BWS without further testing. A score of 2 or 3 warrants genetic testing. A score of less than two does not meet the criteria for testing.[16]

Molecular Diagnosis

Various molecular aberrations cause BWS and mosaicism. The molecular diagnosis of this condition requires a multistep approach, and a negative test does not exclude the diagnosis. Testing is usually performed on blood leukocyte DNA. However, samples from buccal swabs, skin fibroblasts, or surgically resected mesenchymal tissues can improve the detection.

Several testing approaches have been recommended. The most widely used are the following:

- Methylation analysis is considered the first-line testing modality since methylation alteration can be detected in most BWS cases with known molecular etiology. Further studies, such as copy number variant (CNV) identification, may help determine the exact molecular mechanism.

- Sequencing analysis (gene-targeted sequencing) performed if methylation analysis is negative. This test is useful in detecting pathogenic variants of chromosome 11p.15 genes, especially CDKN1C mutations.

- Chromosomal microarray, SNP array, or microsatellite analysis detects microdeletions, microduplications, or length of the paternal uniparental disomy region of chromosome 11.

- Karyotype or fluorescence in situ hybridization detects chromosomal defects associated with BWS, such as duplication, inversion, or translocation of chromosome 11p15.5.

The choice of molecular diagnostic method often depends on the availability of resources, the specific clinical presentation of the individual, and the suspected genetic mechanism underlying the condition.

Prenatal Diagnosis

A positive family history or a suspicion of BWS based on clinical features merits genetic testing and counseling. Methylation analysis and CDKN1C sequencing are the preferred prenatal diagnostic tests. Postnatal confirmation must be obtained when indicated.

Treatment / Management

A qualified healthcare provider should coordinate specialty care for each patient. Once a diagnosis of BWS is made or suspected, anticipatory medical management is required, including a comprehensive plan of supportive medical and surgical care when necessary. Treatment should be individualized, given the high heterogenicity and variety of clinical features.[17][18](B3)

Prenatal Management

Expect fetal or maternal complications in suspected or confirmed cases. Such complications include preeclampsia, congenital anomalies, macrosomia-related injuries, and postnatal hypoglycemia. Ideally, delivery should occur in an institution with a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Neonatal Hypoglycemia

Glucose monitoring should be performed during the first 48 hours of life. Newborns with hypoglycemia should be treated according to standard guidelines. Fasting blood glucose, insulin, and ketone tests are recommended before nursery discharge if hypoglycemia is not detected after 48 hours. Severe persistent hyperinsulinism warrants further investigation.

Growth Anomalies

Growth should be regularly monitored, with growth charts modified for BWS patients. Interventions for possible overgrowth may be considered. Lateralized overgrowth should be measured at least yearly. A leg-length discrepancy warrants a pediatric orthopedic surgery referral. In contrast, arm-length asymmetry may simply be monitored. This symptom does not warrant surgical intervention unless it presents with severe functional limitations.

Macroglossia

Feeding problems require the involvement of infant feeding specialists and dietitians. For suspected airway obstruction, thorough evaluation includes sleep studies and pulmonary and otorhinolaryngology consultations. Tongue-reduction surgery is indicated for macroglossia-related complications, such as feeding difficulties, persistent drooling, speech difficulties, dental malocclusion, and appearance-related psychosocial problems. Surgery is usually performed after age 1 or earlier in cases of severe airway obstruction.

Abdominal Wall Defects

There are no specific recommendations for individuals with BWS compared to others with these conditions. The management of abdominal wall defects in BWS is tailored to the individual's specific circumstances. Surgical intervention may be considered based on the individual's overall health status, the size of the defect, and the presence of associated complications. Surgical repair is often delayed until the child is medically stable and strong enough to tolerate the procedure.

Cardiac Anomalies

A baseline clinical cardiovascular examination should be performed as soon as a BWS clinical diagnosis is made. The patient may be referred to a pediatric echocardiologist for suspected abnormalities. Annual follow-up and electrocardiograms are recommended for patients with a known IC2 molecular aberration.

Renal Complications

Clinical and ultrasonographic evaluation for nephrological anomalies should be made at diagnosis and during the transition to adult medical care. Nephrology and urology referrals are necessary if anomalies are detected. Nephrocalcinosis and renal stones should be monitored concurrently with abdominal surveillance for tumors.

Embryonal Tumors

BWS is a recognized cancer predisposition syndrome. The estimated tumor risk is 5% to 10% in the 1st decade of life, with the highest incidence during the first 2 years. Different tumor screening protocols have been proposed with the common goals of early detection, reduced morbidity, and increased survival.

The tumor surveillance protocol used in the United States includes abdominal ultrasound and serum α-fetoprotein at diagnosis, then every 3 months until age 4 years. Ultrasound screening should continue every 3 to 4 months until age 7 or 8 years. Abdominal ultrasound identifies the most commonly associated tumors, including Wilms tumor, hepatoblastoma, neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and adrenal carcinoma. Serum α-fetoprotein levels are used for monitoring hepatoblastoma. However, this practice is controversial since infants with BWS often have higher α-fetoprotein levels, obscuring interpretation. Additionally, repeated blood collection by venipuncture can be traumatic to young patients.

Although some molecular defects have a greater predisposition for certain types of cancer, most institutions apply the same protocol to all BWS patients regardless of the molecular subtype. Studies suggest that genetically guided stratified tumor screening may be useful for further management.

Neurological Manifestations

Cognitive development is usually normal. However, monitoring by a pediatrician is recommended, especially for patients with chromosomal anomalies or a history of perinatal complications, eg, prematurity, birth trauma, and neonatal hypoglycemia.

Late-Onset Complications

A comprehensive evaluation at age 16 to 18 years is recommended to detect any complications that require follow-up by adult healthcare services. Genetic counseling should be offered for family planning. Continuous education and guidance for both individuals with BWS and their families are essential.

Psychological and Counseling Aspects

An individualized care plan for BWS includes psychological services, specialist counseling, and family support. Promoting self-esteem and confidence is essential for individuals with this condition. Encouraging the patients' strengths, supporting their achievements, and emphasizing their value beyond their condition can help foster a positive self-image. Families should receive contact information for BWS support groups at diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Other overgrowth syndromes include the following:

- Isolated hemihyperplasia

- Sotos syndrome

- Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome

- Costello syndrome

- Perlman syndrome

- Weaver syndrome

- NF1-microdeletion syndrome

- Proteus syndrome

The diagnosis is made after a comprehensive clinical assessment, including family history, physical findings, and confirmation with genetic or molecular analysis when necessary. A particular consideration in the differential diagnosis of BWS is isolated hemihyperplasia since these conditions often share similar epigenetic chromosome 11p15 alterations. Hemihypertrophy is a feature of both conditions.

The following disorders also have symptoms similar to BWS:

- Trisomy 8 mosaicism

- Congenital hypothyroidism

- Mucopolysaccharidoses, eg, Hurler, Hunter, and Maroteaux–Lamy syndromes

- Gangliosidoses

- Pompe disease

Neonatal macrosomia, macroglossia, and hypoglycemia should prompt a comprehensive evaluation for other diagnoses, such as maternal diabetes mellitus. Other causes of developmental delay must be considered in children with developmental delay but without chromosomal abnormalities or a history of prematurity, birth trauma, or neonatal hypoglycemia.[19]

Prognosis

The prognosis varies depending on the symptoms' severity, molecular subtype, time of diagnosis, and occurrence of BWS-related tumors. Most patients with BWS have an average life expectancy. Adults with BWS may have less pronounced growth or facial abnormalities. Early diagnosis, anticipatory guidance, tumor screening, and timely management of complications will contribute to healthy outcomes.

Complications

The following are some of the complications observed in patients with BWS:

- Perinatal: gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes mellitus, vaginal bleeding, polyhydramnios, prematurity, and macrosomia-related complications, such as cephalohematoma and brachial plexus injury

- Neonatal: prematurity, macroglossia-related breathing and feeding difficulties, hypoglycemia, and, rarely, cardiomyopathy

- Childhood to adulthood: macroglossia-related speech or feeding difficulties, genetic or perinatally acquired cognitive impairment, embryonal tumors like Wilms tumor and hepatoblastoma, nephrocalcinosis, nephrolithiasis, renal cysts, recurrent urinary tract infections, scoliosis from leg-length discrepancy, male infertility, and coping issues

Early detection, appropriate surveillance, and timely intervention are crucial in managing complications and improving outcomes for individuals with BWS.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Preventing complications associated with BWS primarily entails early detection, regular monitoring, and proactive management. While it's not always possible to prevent complications, the following measures can help minimize risks and optimize the care of individuals with BWS:

- Regular medical follow-ups and monitoring

- Tumor surveillance and screening

- Hypoglycemia management

- Early intervention for macroglossia

- Orthopedic and musculoskeletal assessments

- Psychological support

Patients and their families should be offered counseling, education, support, and guidance as soon as a diagnosis of BWS is suspected. Clinicians can share contact information for BWS support groups and resources, such as the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) and the Beckwith-Wiedemann Children’s Foundation International, as part of the holistic approach to managing patients.

Pearls and Other Issues

The following are the most important points to remember in BWS management:

- BWS is a heterogeneous syndrome affecting multiple organ systems. Classic features may or may not be noted at birth.

- The etiology of BWS is complex. Most cases arise from sporadic molecular alterations on chromosome 11p15.

- The index of suspicion should be high when evaluating patients with possible BWS. Genetic testing must be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

- Anticipatory guidance about BWS complications, particularly tumors, is crucial in caring for affected patients, given the high risk of developing malignancies early in life.

- Prompt diagnosis and a holistic, multidisciplinary management approach result in better outcomes.

Each person with BWS is unique, and their care plan should be individualized based on their specific needs, health status, and any associated complications they may experience.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Interprofessional team management helps enhance outcomes for patients with BWS. The following are the members of the interprofessional team:[16]

-

Primary care physician or pediatrician works closely with patients and their families to coordinate care, consults, and appropriate follow-up. Comprehensive periodic evaluations and a smooth transition to adult healthcare services for teens are tasks the primary care provider can arrange.

-

The pediatric or medical geneticist has expertise in diagnosing and managing BWS. This provider also oversees the overall management plan.

-

A radiologist interprets imaging tests and helps in diagnosis and treatment planning.

-

Nursing staff identifies infant feeding difficulties, administers medications to hospitalized patients, helps coordinate care, and reinforces patient education.

- An otorhinolaryngologist manages cleft palate and macroglossia-related airway issues.

-

The pediatric surgeon treats abdominal wall defects surgically when warranted.

-

An oncologist specializes in tumor surveillance and management. These clinicians play a critical role in detecting and managing tumors associated with BWS.

-

An endocrinologist monitors and manages hormonal issues, such as hypoglycemia, that may arise in individuals with BWS.

-

Orthopedic specialists assess and manage musculoskeletal problems, such as limb asymmetry and other overgrowth-related orthopedic complications in patients with BWS.

-

A genetic counselor provides information, guidance, and support to affected individuals and families regarding BWS' genetic basis and inheritance patterns. This provider also emphasizes the importance of genetic testing.

-

A speech and language therapist helps address macroglossia-related speech and communication difficulties.

-

A physical therapist assists in managing musculoskeletal issues and developing strategies to enhance mobility and function.

- Dietitians and feeding specialists help manage specific macroglossia-related feeding problems.

- A mental health professional (psychologist or psychiatrist) offers psychological support to help patients with BWS cope with emotional stressors.

- A social worker or care coordinator assists with coordinating appointments, accessing resources, and supporting families navigating healthcare systems.

Collaboration and communication among these professionals are essential to developing and implementing a comprehensive, personalized care plan for patients with BWS.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Patients With BWS. Photos of 6 patients with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome due to (A) IC2 loss of methylation (IC2 LOM), (B) IC1 gain of methylation (IC1 GOM), (C) chromosomal rearrangements (deletions, duplications), (D) paternal uniparental isodisomy 11 (pUPD), (E) genome-wide paternal uniparental isodisomy (GWpUPD), and (F) CDKN1C mutation. Written consent was obtained from the parents of every participant to publish these identifying images.

Kathleen H. Wang, Jonida Kupa, Kelly A. Duffy, Jennifer M. Kalish. "Diagnosis and Management of Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome." Frontiers in Pediatrics 7 (2020). (CC-BY 4.0)

References

Cammarata-Scalisi F, Avendaño A, Stock F, Callea M, Sparago A, Riccio A. Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome: clinical and etiopathogenic aspects of a model genomic imprinting entity. Archivos argentinos de pediatria. 2018 Oct 1:116(5):368-373. doi: 10.5546/aap.2018.eng.368. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30204990]

Wang KH, Kupa J, Duffy KA, Kalish JM. Diagnosis and Management of Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome. Frontiers in pediatrics. 2019:7():562. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00562. Epub 2020 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 32039119]

Cohen MM Jr. Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome: historical, clinicopathological, and etiopathogenetic perspectives. Pediatric and developmental pathology : the official journal of the Society for Pediatric Pathology and the Paediatric Pathology Society. 2005 May-Jun:8(3):287-304 [PubMed PMID: 16010495]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEnklaar T, Zabel BU, Prawitt D. Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome: multiple molecular mechanisms. Expert reviews in molecular medicine. 2006 Jul 17:8(17):1-19 [PubMed PMID: 16842655]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWeksberg R, Shuman C, Beckwith JB. Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2010 Jan:18(1):8-14. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.106. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19550435]

Mussa A, Molinatto C, Cerrato F, Palumbo O, Carella M, Baldassarre G, Carli D, Peris C, Riccio A, Ferrero GB. Assisted Reproductive Techniques and Risk of Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome. Pediatrics. 2017 Jul:140(1):. pii: e20164311. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-4311. Epub 2017 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 28634246]

Mussa A, Di Candia S, Russo S, Catania S, De Pellegrin M, Di Luzio L, Ferrari M, Tortora C, Meazzini MC, Brusati R, Milani D, Zampino G, Montirosso R, Riccio A, Selicorni A, Cocchi G, Ferrero GB. Recommendations of the Scientific Committee of the Italian Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome Association on the diagnosis, management and follow-up of the syndrome. European journal of medical genetics. 2016 Jan:59(1):52-64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2015.11.008. Epub 2015 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 26592461]

MacFarland SP, Duffy KA, Bhatti TR, Bagatell R, Balamuth NJ, Brodeur GM, Ganguly A, Mattei PA, Surrey LF, Balis FM, Kalish JM. Diagnosis of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome in children presenting with Wilms tumor. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2018 Oct:65(10):e27296. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27296. Epub 2018 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 29932284]

Gazzin A, Carli D, Sirchia F, Molinatto C, Cardaropoli S, Palumbo G, Zampino G, Ferrero GB, Mussa A. Phenotype evolution and health issues of adults with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2019 Sep:179(9):1691-1702. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.61301. Epub 2019 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 31339634]

Elliott M, Bayly R, Cole T, Temple IK, Maher ER. Clinical features and natural history of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome: presentation of 74 new cases. Clinical genetics. 1994 Aug:46(2):168-74 [PubMed PMID: 7820926]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDeBaun MR, Tucker MA. Risk of cancer during the first four years of life in children from The Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome Registry. The Journal of pediatrics. 1998 Mar:132(3 Pt 1):398-400 [PubMed PMID: 9544889]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWeksberg R, Nishikawa J, Caluseriu O, Fei YL, Shuman C, Wei C, Steele L, Cameron J, Smith A, Ambus I, Li M, Ray PN, Sadowski P, Squire J. Tumor development in the Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome is associated with a variety of constitutional molecular 11p15 alterations including imprinting defects of KCNQ1OT1. Human molecular genetics. 2001 Dec 15:10(26):2989-3000 [PubMed PMID: 11751681]

Zarate YA, Mena R, Martin LJ, Steele P, Tinkle BT, Hopkin RJ. Experience with hemihyperplasia and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome surveillance protocol. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2009 Aug:149A(8):1691-7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32966. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19610116]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGaston V, Le Bouc Y, Soupre V, Burglen L, Donadieu J, Oro H, Audry G, Vazquez MP, Gicquel C. Analysis of the methylation status of the KCNQ1OT and H19 genes in leukocyte DNA for the diagnosis and prognosis of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2001 Jun:9(6):409-18 [PubMed PMID: 11436121]

Ibrahim A, Kirby G, Hardy C, Dias RP, Tee L, Lim D, Berg J, MacDonald F, Nightingale P, Maher ER. Methylation analysis and diagnostics of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome in 1,000 subjects. Clinical epigenetics. 2014:6(1):11. doi: 10.1186/1868-7083-6-11. Epub 2014 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 24982696]

Brioude F, Kalish JM, Mussa A, Foster AC, Bliek J, Ferrero GB, Boonen SE, Cole T, Baker R, Bertoletti M, Cocchi G, Coze C, De Pellegrin M, Hussain K, Ibrahim A, Kilby MD, Krajewska-Walasek M, Kratz CP, Ladusans EJ, Lapunzina P, Le Bouc Y, Maas SM, Macdonald F, Õunap K, Peruzzi L, Rossignol S, Russo S, Shipster C, Skórka A, Tatton-Brown K, Tenorio J, Tortora C, Grønskov K, Netchine I, Hennekam RC, Prawitt D, Tümer Z, Eggermann T, Mackay DJG, Riccio A, Maher ER. Expert consensus document: Clinical and molecular diagnosis, screening and management of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome: an international consensus statement. Nature reviews. Endocrinology. 2018 Apr:14(4):229-249. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.166. Epub 2018 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 29377879]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRednam SP. Updates on progress in cancer screening for children with hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes. Current opinion in pediatrics. 2019 Feb:31(1):41-47. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000709. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30531401]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKalish JM, Doros L, Helman LJ, Hennekam RC, Kuiper RP, Maas SM, Maher ER, Nichols KE, Plon SE, Porter CC, Rednam S, Schultz KAP, States LJ, Tomlinson GE, Zelley K, Druley TE. Surveillance Recommendations for Children with Overgrowth Syndromes and Predisposition to Wilms Tumors and Hepatoblastoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2017 Jul 1:23(13):e115-e122. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0710. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28674120]

Suri M. Approach to the Diagnosis of Overgrowth Syndromes. Indian journal of pediatrics. 2016 Oct:83(10):1175-87. doi: 10.1007/s12098-015-1958-1. Epub 2015 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 26680784]