Introduction

Bancroftian filariasis, accounting for 90% of the lymphatic filariasis cases, is one of the most common etiology of acquired lymphedema. It is the second leading infectious cause of disability worldwide after leprosy.[1][2] The disease primarily involves lymphatic system with clinical manifestations ranging from acute, such as acute adenolymphangitis, filarial fever, tropical pulmonary eosinophilia to chronic, such as hydrocele, lymphedema, and elephantiasis in the most severe of cases.[3]

In filariasis, there is chronic inflammation of the lymphatics, leading to fibrosis, which eventually leads to lymphedema. While the legs are involved in most cases, the lymphedema can also involve the genitals, arms, and breasts.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

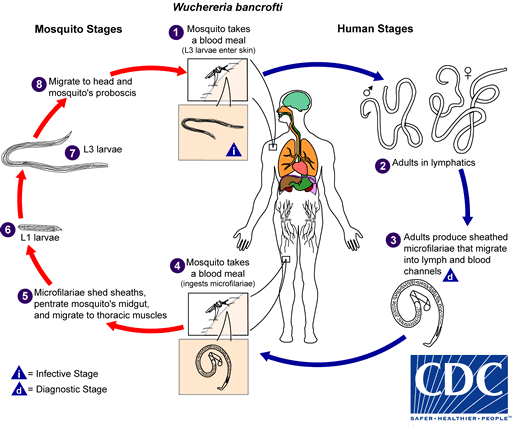

The causative agent of the disease is the roundworm, Wuchereria bancrofti.[4][5] It multiplies inside human lymphatics releasing immature larvae known as microfilariae into the bloodstream. Mosquitoes ingest these larval forms when they feed on infected human blood and spread the disease to the other people via their bite.[6]

Epidemiology

Bancroftian filariasis is a chronic neglected tropical disease endemic in over 72 countries. These endemic regions include South East Asia, Sub Saharan Africa, islands of Pacific, and selected areas in Latin America. An estimated 70 million people in the world suffer from lymphatic filariasis with Wuchereria bancrofti accounting for more than 90% of the cases.[7][8] There are approximately 36 million people worldwide rendered morbidly ill by the disease with up to 25 million people suffering from hydrocele and 15 million from debilitating lymphedema.[9]

The disease holds paramount epidemiological significance as World Health Organization (WHO) plans to eliminate it by 2020.[8][10] This effort will not only prevent unnecessary suffering but also contribute to the reduction of poverty as the expenditure on dealing with the morbidities is enormous.

Pathophysiology

The life cycle of Wuchereria bancrofti is extant in two hosts: man (definitive host) and mosquito (intermediate host). Mosquitoes of the genera Aedes, Anopheles, Culex, and Mansonia ingest microfilariae when they bite humans.[11] The ingested microfilaria travel through the stomach wall into the flight muscles, where they mature into infective larval stages. These infectious form eventually migrate to the proboscis from where they get injected into the human skin during the bite. They then travel through the dermis into the regional lymphatics and further mature into male and female larval forms. Female larvae are responsible for releasing microfilariae into the bloodstream. Microfilariae exhibit circadian periodicity in the peripheral circulation reaching their highest concentration in the blood at night.[6]

The exact mechanism behind the lymphatic damage involves a complex interplay of lymphangiectasia and inflammatory reactions triggered by the dying worms. Adult filarial worms usually reside in the afferent, efferent, and hilar lymphatics, causing blockage and subclinical lymphangiectasia. Moreover, lymphatic damage also results from the host’s immune response to the parasite’s endosymbiont Wolbachia. Antigens released by the dying worms trigger inflammatory reactions causing lymphatic damage.

Clinical progression of the disease varies in individuals depending on the host’s immune response. Chronicity of the infection has been attributed to the suppression of Th1 and Th2 immune responses. The asymptomatic carrier state has links to the synergistic interplay between poly-specific natural IgG4 and anti-filarial IgG4 in blocking the pathogenesis.[12][13][14] Genetic predisposition to lymphedema and prenatal exposure in endemic areas also play a vital role.

Histopathology

Histopathologic diagnosis is by identifying microfilariae on a peripheral thick smear. Adult forms or eggs may also be seen aiding in the diagnosis. Microscopic examination of an affected tissue usually shows multiple adult filarial worms or microfilaria surrounded by dense eosinophilic infiltration and giant cells. Giemsa staining helps in recognizing microfilarial morphology. The absence or presence of a sheath and the pattern of nuclei in their tail are the key features used to differentiate among various species. Features pathognomonic of Wuchereria bancrofti are i) presence of sheath ii) absence of nuclei in the tail. Other distinctive features include cephalic space length: breadth ratio of 1 to 1, and spherical nuclei which are regularly placed and appear in a regular row, well separated without any overlapping.[15]

History and Physical

Individuals can broadly classify into the following clinical categories:

- Endemic normals (EN) – subjects living in endemic areas but free of infection and not showing any symptoms of the disease

- Chronic (CH) – individuals with chronic sequelae of the disease such as elephantiasis, hydrocele or both for more than four years

- Asymptomatic carriers (AS) – individuals with microfilaremia and antigenemia not showing any clinical symptoms.[14]

Clinical manifestations can subdivide into acute and chronic:

Acute presentations include:

- Acute adenolymphangitis - occurs as a result of the host’s immune response to the antigens released by dying worms - it is characterized by repeated bouts of sudden-onset fever and painful lymphadenopathy. Genitals are commonly involved in males, resulting in painful epididymitis.

- Filarial fever - characterized by episodes of self-limiting fever without any associated lymphadenopathy.

- Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia - characterized by repeated bouts of dry nocturnal cough and wheeze

Chronic presentations include:

- Lymphedema - the most common presentation that develops over a long period due to chronic lymphatic damage. It characteristically presents with swelling of the limbs either upper or lower depending on the involvement of inguinal or axillary lymphatic vessels. Pitting edema develops in the early stages of the disease, which later progresses into brawny non-pitting type. Elephantiasis is the most severe type of lymphedema characterized by severe swelling of the limbs, genitalia, and breasts. The skin becomes thick and hard, owing to hyperpigmentation and hyperkeratosis.

- Hydrocele - this is one of the debilitating morbidities associated with chronic disease. It can be unilateral or bilateral, leading to enlargement of the scrotum. It can be very large, reaching up to 40 cm.

Other manifestations include chyluria, hematuria, inguinal and axillary lymphadenopathy, testicular or inguinal pain, and skin exfoliation.

Evaluation

A detailed inquiry focusing on travel history and establishing the endemicity and chronicity of condition is critical to making a diagnosis. A complete blood count usually shows eosinophilia. Despite recent advances, a nocturnal peripheral thick smear followed by Giemsa staining demonstrating microfilariae in the bloodstream remains the mainstay of diagnosis. Newer methods include circulating filarial antigen test, which has approximately 97% sensitivity and 100% specificity.[16] It is gradually replacing the older nocturnal thick smear test due to its dipstick nature and ability to diagnose the condition in microfilariae-negative patients.[17] Other techniques include membrane filtration method, ultrasonography (filarial dance sign), lymphoscintigraphy, immunochromatographic tests and molecular techniques like in situ hybridization (ISH), fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), and polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Treatment / Management

Diethylcarbamazine (DEC) remains the mainstay of treatment worldwide. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends a 1-day or 12-day course of DEC (6 mg/kg/day). Those belonging to onchocerciasis or loiasis co-endemic areas must not be prescribed DEC as it can result in a fatal adverse reaction. Filaricidal action of DEC induces an immunological reaction similar to the Mazzotti reaction seen in onchocerciasis, characterized by headache, joint pain, dizziness, anorexia, malaise, and urticaria. Doxycycline and ivermectin or albendazole is the recommended combination in these individuals. Individuals with chronic disease such as elephantiasis or hydrocele will not benefit from pharmacologic therapy. Surgical treatment may be necessary for those with hydrocele. Patients with lymphedema should be managed by a lymphedema therapist emphasizing the role of basic principles of care such as hygiene, elevation, exercises, skin, and wound care, and wearing appropriate shoes. Steroids, although not widely used, can help in reducing the extent of lymphedema seen in these patients. There is limited evidence for the role of doxycycline as some studies advocate the use of doxycycline (200mg/day for 4 to 6 weeks) in adult worm killing and preventing the progression of lymphedema. Suramin is widely used in onchocerciasis, yet its role remains uncertain in lymphatic filariasis.

Differential Diagnosis

Bancroftian filariasis is only one cause of lymphatic filariasis. Other conditions involving the lymphatic system can also mimic the disease. It is important to consider age, travel history, family history, endemicity, and socioeconomic status when trying to work out a diagnosis.

The differentials include:

- Brugia malayi

- Brugia timori

- Sporotrichosis

- Lymphosarcoma

- Carcinoma of testis or scrotum

- Congenital hydrocele

- Epidydimal cysts

- Milroy syndrome

- Bacterial lymphadenitis

Prognosis

The response to diethylcarbamazine is excellent for acute forms of the disease. However, those having chronic lymphatic damage in the form of lymphedema or elephantiasis will respond poorly. These chronic forms have a poor prognosis. Patients with hydrocele might respond to surgery, but recurrence is common. The condition is debilitating rendering the person incapable of performing daily activities.

Complications

The grimmest complication of the disease is elephantiasis seen in individuals with long-standing filarial infection. Other complications include hydrocele and adverse reactions from DEC therapy such as encephalopathy and even death when used in loiasis-endemic areas.

Consultations

Patients with a high index of suspicion for bancroftian filariasis require immediate consultation from infectious diseases expert. General surgery/urology consultation is helpful when dealing with hydrocele. If the patient is in the United States, one should contact the CDC.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Avoiding mosquito bites and enforcing vector control measures is crucial to avoid contracting the disease. Tourist should avoid visiting endemic areas. Visitors touring endemic areas should sleep under mosquito nets, wear long sleeves and trousers, and use mosquito repellent on exposed parts of the body. There is currently no vaccine available. Individuals with lymphedema should maintain good personal hygiene and wash affected areas with antiseptic solution daily. Compression stockings, regular exercise, and using a pillow beneath the affected limb at night can help in reducing the swelling. Restricting a fatty diet is extremely important in patients with overt chyluria. Moreover, a high protein diet and foods rich in high medium-chain triglycerides content are recommended patients having chyluria.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Bancroftian filariasis is a mosquito-borne disease caused by the nematode Wuchereria bancrofti.

- The disease is the second most common cause of disability worldwide after leprosy.

- WHO is to target the elimination of the disease by 2020.

- Elephantiasis is the most debilitating complication of the disease

- A nocturnal peripheral thick smear showing microfilariae is diagnostic of the disease.

- Diethylcarbamazine is the mainstay of treatment worldwide.

- Diethylcarbamazine is not for use in patients having concomitant loiasis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Bancroftian filariasis is one of the neglected tropical diseases and is unlikely to be seen in the US. However, clinicians must have a high index of suspicion whenever dealing with immigrants or travelers from endemic areas presenting with limb swelling, hydrocele, lymphadenopathy, or chyluria. Travelers to the tropic should receive education regarding mosquito bite prevention. Since it is a mosquito-borne disease, prevention involves taking vector control measures such as mosquito nets, applying mosquito repellents, wearing trousers and long-sleeved clothes, and reduction of peri-domiciliary water puddles. The two major public health strategies being employed to eliminate the disease include a) mass drug administration (MDA) to reduce the microfilarial density to suboptimal levels for vector transmission b) ensuring the provision of recommended basic package of care in endemic areas to alleviate the suffering caused by the disease.[7][8][9][18]

Upon starting treatment in non-surgical cases, the pharmacist (potentially with a specialty in infectious disease) should educate the patient on compliance with treatment and the need for follow up, as well as verifying dosing and checking for drug interactions. Often most symptoms take months to subside, but disability is rare if the patient completes the treatment course. The lymphedema may decrease but may not completely resolve, and hence the patient must be told to wear compression garments for life. Nursing can provide ongoing education and monitoring, verify treatment compliance, and alert the treating clinician of any issues. For surgical cases, the nursing staff will be involved pre, during, and postoperatively, providing preparation assistance, and postoperative care, and keeping the surgeon informed following the procedure. Even in light of the rarity of this disease, an interprofessional team approach to care is necessary to achieve optimal results for the patient. [Level V]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Maldjian C, Khanna V, Tandon B, Then M, Yassin M, Adam R, Klein MJ. Lymphatic filariasis disseminating to the upper extremity. Case reports in radiology. 2014:2014():985680. doi: 10.1155/2014/985680. Epub 2014 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 24707427]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePryce J, Mableson HE, Choudhary R, Pandey BD, Aley D, Betts H, Mackenzie CD, Kelly-Hope LA, Cross H. Assessing the feasibility of integration of self-care for filarial lymphoedema into existing community leprosy self-help groups in Nepal. BMC public health. 2018 Jan 30:18(1):201. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5099-0. Epub 2018 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 29382314]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChandy A, Thakur AS, Singh MP, Manigauha A. A review of neglected tropical diseases: filariasis. Asian Pacific journal of tropical medicine. 2011 Jul:4(7):581-6. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60150-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21803313]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKatiyar D, Singh LK. Filariasis: Current status, treatment and recent advances in drug development. Current medicinal chemistry. 2011:18(14):2174-85 [PubMed PMID: 21521163]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFamakinde DO. Mosquitoes and the Lymphatic Filarial Parasites: Research Trends and Budding Roadmaps to Future Disease Eradication. Tropical medicine and infectious disease. 2018 Jan 4:3(1):. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed3010004. Epub 2018 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 30274403]

Paily KP, Hoti SL, Das PK. A review of the complexity of biology of lymphatic filarial parasites. Journal of parasitic diseases : official organ of the Indian Society for Parasitology. 2009 Dec:33(1-2):3-12. doi: 10.1007/s12639-009-0005-4. Epub 2010 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 23129882]

. Summary of global update on preventive chemotherapy implementation in 2016: crossing the billion. Releve epidemiologique hebdomadaire. 2017 Oct 6:92(40):589-93 [PubMed PMID: 28984120]

Small ST, Ramesh A, Bun K, Reimer L, Thomsen E, Baea M, Bockarie MJ, Siba P, Kazura JW, Tisch DJ, Zimmerman PA. Population genetics of the filarial worm wuchereria bancrofti in a post-treatment region of Papua New Guinea: insights into diversity and life history. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2013:7(7):e2308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002308. Epub 2013 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 23875043]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAdhikari RK, Sherchand JB, Mishra SR, Ranabhat K, Pokharel A, Devkota P, Mishra D, Ghimire YC, Gelal K, Paudel R, Wagle RR. Health-seeking behaviors and self-care practices of people with filarial lymphoedema in Nepal: a qualitative study. Journal of tropical medicine. 2015:2015():260359. doi: 10.1155/2015/260359. Epub 2015 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 25694785]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceIchimori K, King JD, Engels D, Yajima A, Mikhailov A, Lammie P, Ottesen EA. Global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis: the processes underlying programme success. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2014 Dec:8(12):e3328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003328. Epub 2014 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 25502758]

Erickson SM, Thomsen EK, Keven JB, Vincent N, Koimbu G, Siba PM, Christensen BM, Reimer LJ. Mosquito-parasite interactions can shape filariasis transmission dynamics and impact elimination programs. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2013:7(9):e2433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002433. Epub 2013 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 24069488]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNutman TB. Insights into the pathogenesis of disease in human lymphatic filariasis. Lymphatic research and biology. 2013 Sep:11(3):144-8. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2013.0021. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24044755]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBabu S, Nutman TB. Immunopathogenesis of lymphatic filarial disease. Seminars in immunopathology. 2012 Nov:34(6):847-61. doi: 10.1007/s00281-012-0346-4. Epub 2012 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 23053393]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMishra R, Panda SK, Sahoo PK, Mishra S, Satapathy AK. Self-reactive IgG4 antibodies are associated with blocking of pathology in human lymphatic filariasis. Cellular immunology. 2019 Jul:341():103927. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2019.103927. Epub 2019 May 21 [PubMed PMID: 31130239]

Pandey P, Dixit A, Chandra S, Tanwar A. Cytological diagnosis of bancroftian filariasis presented as a subcutaneous swelling in the cubital fossa: an unusual presentation. Oxford medical case reports. 2015 Apr:2015(4):251-3. doi: 10.1093/omcr/omv027. Epub 2015 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 26634138]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEl-Moamly AA, El-Sweify MA, Hafez MA. Using the AD12-ICT rapid-format test to detect Wuchereria bancrofti circulating antigens in comparison to Og4C3-ELISA and nucleopore membrane filtration and microscopy techniques. Parasitology research. 2012 Sep:111(3):1379-83. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-2870-5. Epub 2012 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 22392137]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTripathi PK, Mahajan RC, Malla N, Mewara A, Bhattacharya SM, Shenoy RK, Sehgal R. Circulating filarial antigen detection in brugian filariasis. Parasitology. 2016 Mar:143(3):350-7. doi: 10.1017/S0031182015001675. Epub 2015 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 26646772]

Specht S, Suma TK, Pedrique B, Hoerauf A. Elimination of lymphatic filariasis in South East Asia. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2019 Jan 22:364():k5198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k5198. Epub 2019 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 30670373]