Introduction

Anti NMDA Receptor encephalitis is an autoimmune encephalitis characterized by complex neuropsychiatric features and the presence of Immunoglobulin G(IgG) antibodies against the NR1 subunit of the NMDA receptors in the central nervous system(CNS). These antibodies are identifiable in the serum or the cerebrospinal; fluid (CSF).[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

This autoimmune encephalitis develops due to the formation and attachment of IgG, particularly IgG1 and G3, to NMDA receptor (NR1) subunit with subsequent internalization of NMDA (glutamate) receptors, reduction of neuronal Ca influx, and decrease in the receptor-dependent synaptic currents.[2] In some patients, antibody production becomes triggered by associated ovarian teratoma and rarely other tumors. Viral encephalitis, particularly Herpes Simplex Virus encephalitis, can correlate with NMDAR antibody production over the ensuing three weeks with subsequent development of autoimmune encephalitis.[3] In most cases, the exact etiology of antibody production remains unknown, however, regardless of the origin, the pathogenesis leads to a superfluous production of autoantibodies by intrathecal plasma cells.

Epidemiology

Although this is a rare disease (one affected out of 1.5 million people per year), anti NMDAR encephalitis is the best known and probably the most common autoimmune encephalitis.[4] In the California Encephalitis Project, the incidence of anti NMDAR encephalitis was higher than the incidence of any individual viral encephalitis.[5] There have been reports of anti NMDAR encephalitis has been reported in infants of 2 months of age to up to an advanced age of 85 years old. Females are afflicted four times more commonly. Young adult females between 25 and 35 years of age are most commonly affected.

Pathophysiology

Autoimmune encephalitis was classified in the past as paraneoplastic or non-paraneoplastic, depending on whether there are any identifiable tumor-associated antibodies. These paraneoplastic antibodies included anti-neuronal nuclear antibody type 1 (anti-Hu), anti-Ri, or Yo, etc. With a better understanding of the pathophysiology of different auto-immune encephalitis, the more nuanced way of classification is pathophysiologically based. The modern-day classification is to classify the immune encephalitis according to the targets of the antibodies. The classical paraneoplastic encephalitis, as named above, is mediated through a predominant T-cell mediated mechanism with cytotoxic T cells demonstrated in the pathological specimens. These immune responses are the result of molecular mimicry between the neuronal tissue antigen and tumor antigens. The antibodies themselves are not pathogenic. These antibodies direct their activity towards intracellular constituents. The other class of autoimmune encephalitis consists of antibodies directed against synaptic or cell-surface antigens such as anti-NMDAR, anti-GAD, anti-VGKC antibody-mediated encephalitides. These are real antibody or B-cell mediated autoimmune encephalitis with real pathogenic antibodies.[6] Anti-NMDAR antibody immune encephalitis is a B-cell mediated autoimmune encephalitis with an actual pathogenic antibody that can be removed by plasma exchange resulting in improvement of the underlying pathology.

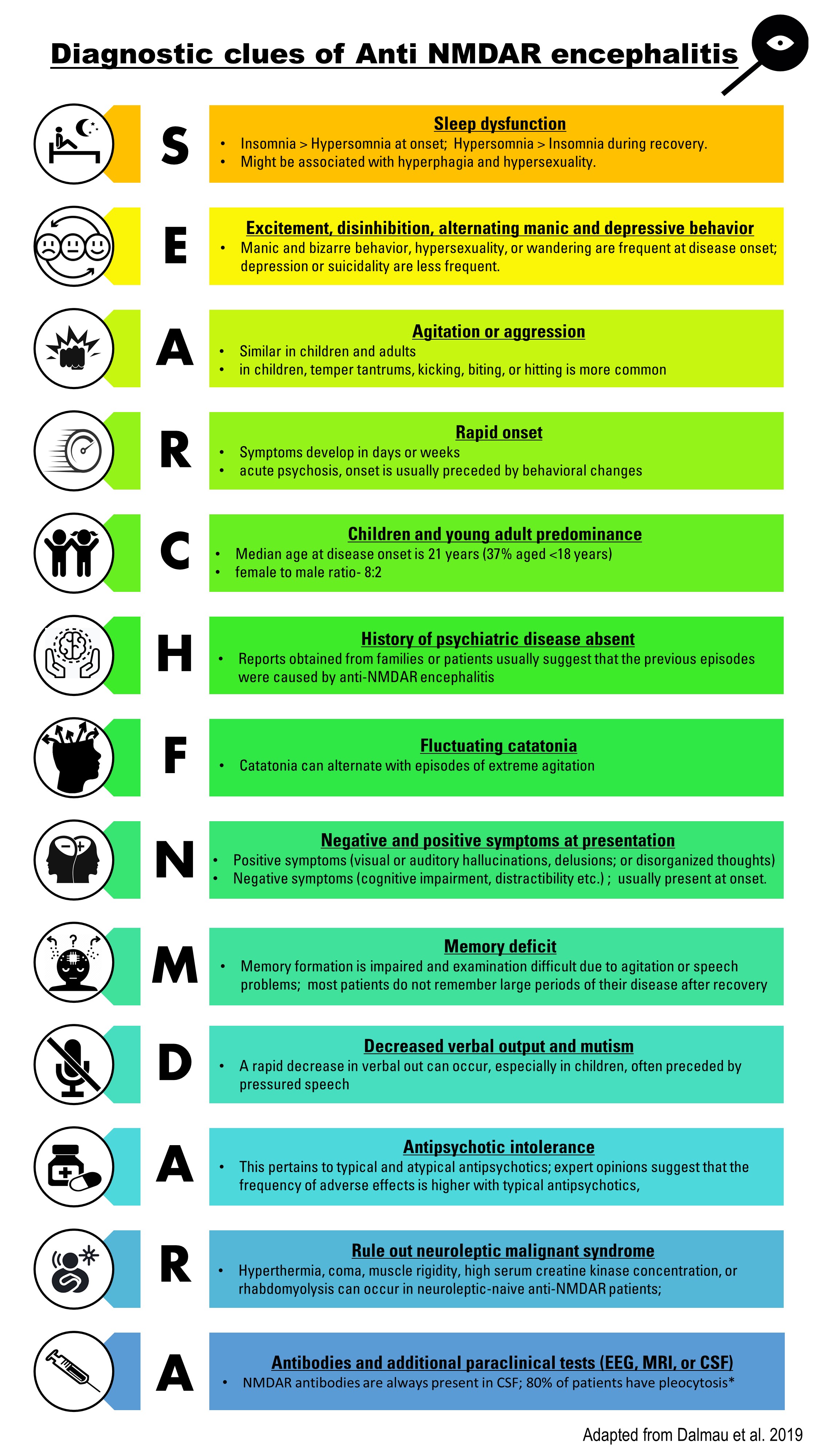

History and Physical

Presentation of anti NMDAR encephalitis has been categorized into five distinct phases: prodromal phase, psychotic phase, unresponsive phase, hyperkinetic phase, and recovery phase.[7]

The disease starts with a prodromal state mimicking common viral infections. But within weeks to a few months(less than 3 months), complex neuropsychiatric features emerge rapidly during the psychotic phase. Presenting clinical features may be different between children and adults. Adults usually present with psychiatric symptoms compared with movement disorders or seizures as the most common presentation in children. Acute or subacute behavioral symptoms are the most common presenting features in adult patients. Though there is no specific psychiatric phenotype, variable positive and negative psychiatric symptoms such as visual or auditory hallucination, acute schizoaffective episodes, depression, mania, and addictive or eating disorders can appear rapidly within days to weeks in these patients with no prior psychiatric diagnosis. The onset occurs fairly quickly in contrast to the slow progression noted in primary psychiatric diseases. Many patients get admitted to the psychiatric inpatient unit due to severe presentation and spend weeks for symptomatic management. Although several patients would have coexistent neurological features at the onset, some may develop within a few weeks of presentation. Importantly, some patients are intolerant to neuroleptics and can develop hyperthermia, muscle rigidity, rhabdomyolysis, or coma after exposure to neuroleptics.

In contrast to more prevalent positive symptoms in schizophrenia, anti-NMDAR encephalitis patients have both positive and negative symptoms. Besides a diverse range of neuropsychiatric symptoms- apathy, anxiety, fluctuating sensorium, bizarre behaviors, hypersexuality, wandering, aphasia, amnesia, apraxia, sleep-wake cycle disruption with severe insomnia, delusion- many patients, particularly children and male adults, present with seizures, both focal and generalized seizures. Seizures can be resistant to antiepileptic drugs(AEDs) and may evolve to status epilepticus or even refractory status epilepticus. The psychotic phase evolves into the unresponsive phase characterized by mutism, decreased motor activity, and catatonia. Following the unresponsive phase, a hyperkinetic phase with autonomic instability and prominent movement disorders becomes evident. In the presence of notable autonomic disruption - labile blood pressures and heart rates, cardiac arrhythmias, temperature instability, and central hypoventilation- some patients require admission to the ICU and in some instances, use of mechanical ventilation and cardiac pacemaker. The classic movement disorder in this phase is oro-lingual dyskinesias with lip-smacking, tongue protrusion, jaw movements, but a diverse range of movement disorders can present in this phase, such as automatisms, dyskinesia, dystonia, and choreoathetosis, myorhythmia, blepharospasm, oculogyric crisis, and hemiballismus. With adequate immunotherapy and supportive care, the patients may enter the recovery phase after months of treatment. Recovery of language function and behavioral symptoms occurs at the end.

Rarely, anti-NMDAR encephalitis patients develop demyelinating disorders such as neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder- concurrently, preceding or following the encephalitis- with disease-specific antibody production(aquaporin-4 or myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein).[8]

Evaluation

Routine laboratory testing is usually nonspecific. Anti NMDAR IgG antibodies, detected by indirect immunofluorescence assay in the serum and the CSF, are diagnostic for the disease. Antibody titers are higher in the CSF, and in some cases, diagnosis is possible after CSF testing with concurrent negative serum reports. CSF also can have low-grade hypercellularity and oligoclonal bands.[1] Brain MRI can be normal, but nonspecific white and gray matter T2/FLAIR signal hyperintensity can be present, most commonly in the hippocampus. Diffusion restriction positivity has been reported, as well as cerebellar atrophy, as the only irreversible radiologic finding with this encephalitis.[9]

One specific interictal EEG finding is extreme delta brushes(bursts of beta activity superimposed on diffuse delta activities)- a finding commonly seen in healthy premature neonates. Other EEG abnormalities- generalized theta and delta slowing, subclinical seizures, nonconvulsive status epilepticus- are frequently present but nonspecific findings of encephalopathy or encephalitis. After confirmation of the diagnosis, a comprehensive evaluation should be done to detect underlying malignancy. Whole-body CT, MRI abdomen and transvaginal ultrasound are commonly employed to detect tumors. Transvaginal ultrasonography is the most crucial test for young women presenting with the illness due to the high incidence of underlying ovarian teratoma. If these tests are unrevealing, PET scans and exploratory laparotomy are options.[10] In cases of negative initial screening, follow-up MRI abdomen and pelvis should be repeated every six months for at least four years.[11]

Treatment / Management

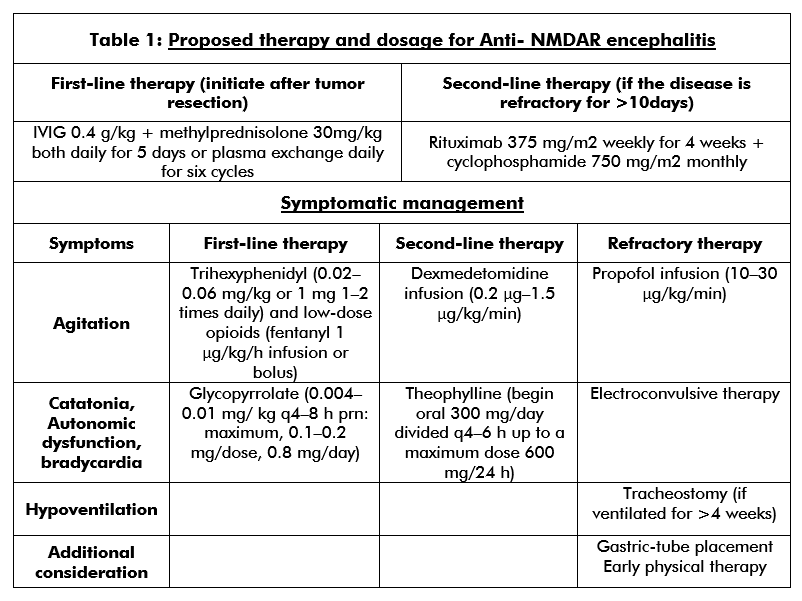

Early diagnosis and treatment can be beneficial for the final outcome.[1] Prompt treatment can be initiated before the final diagnosis in case of a reasonable degree of suspicion after collecting serum and CSF samples for confirmation of autoimmune encephalitis.[12] Expeditious immunomodulatory/immunosuppressive therapies with corticosteroids, immunoglobulin infusion(IVIG), and plasmapheresis (PLEX) are first-line therapies, as well as tumor removal if applicable, with robust supportive therapies.[13][14](B2)

However, which of these immunotherapies should start first, and if combination therapy should be used from the beginning has not been researched in a controlled fashion. Additionally, for sequential therapies, the optimal order of therapies has not been standardized. PLEX has been utilized more frequently in the beginning due to its ability to quickly remove the autoantibodies, and recent retrospective studies suggested PLEX therapy before IVIG administration may improve outcomes. Unfortunately, only approximately half of the patients would respond to first-line therapy. Rituximab, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil have been used as second-line therapies if clinical improvement does not occur after four weeks of treatment with first-line therapy. Some experts recommended the use of rituximab early in the disease process as first-line therapy. For refractory patients, bortezomib(proteasome inhibitor), alemtuzumab(humanized monoclonal antibody against CD52), intrathecal methotrexate, and tocilizumab(a monoclonal antibody against interleukin-6 receptor) can work in a small number of patients with success.

Seizure management in the acute phase can be difficult and requires AEDs along with immunotherapy. However, these patients do not develop epilepsy as the seizure improves with the improvement of encephalitis. A retrospective series reported that valproate, levetiracetam, and carbamazepine had been similarly effective, but carbamazepine was associated with fewer side effects.[15] Gradual reduction of AEDs is possible during follow-up, and most can be discontinued in 2 years without seizure recurrence. Antipsychotic agents are frequently used to treat behavioral symptoms, but neuroleptic malignant syndrome can occur.[16] Benzodiazepines and electroconvulsive therapy have been utilized to treat catatonia. Abnormal movements associated with this encephalitis are challenging to control and require a high dose of sedative medications, botulinum toxin, or tetrabenazine.ICU management is essential during the severe phase of the disease for several reasons: airway protection, altered cognition, dyskinesias, seizures, abnormal behavior, temperature instability, heart rate variability, and arrhythmia.[17](B3)

Herpes simplex encephalitis is the commonest sporadic encephalitis. Any patient who presented with clinical features of acute encephalitis should be treated empirically with IV acyclovir, pending the result of HSV PCR results. Acyclovir will be continued or stopped depending on the outcome of the PCR test. It is essential to recognize the fact that early recurrence of HSV encephalitis within 2 to 3 weeks of the encephalitis is often due to anti-NMDAR encephalitis triggered by the viral encephalitis. It is reasonable and understandable that HSV is a neurotropic virus with predominant involvement of the limbic gray matter, which has a high concentration of NMDA receptors. The viral infection may lead to a higher likelihood of release of the receptor and subsequent antibody formation and secondary immune encephalitis.

Differential Diagnosis

- Another autoimmune encephalitis

- Primary psychiatric disorder

- Viral encephalitis

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

- Catatonia

- Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

- Mitochondrial encephalitis

- Cerebral space-occupying lesions

- Exposure to drugs, toxins, or withdrawal symptoms

Prognosis

There are some independent predictors of worse outcomes: requirement of ICU stay, treatment delay over four weeks, no improvement after four weeks of treatment, abnormal brain MRI, and white blood cell greater than 20 cells/microL. All these variables can be given one point each to form a functional score. A higher score is associated with poor functional status at one year from the disease onset, but this should not be used to guide therapy or determine the final prognosis as one-third of the patients with poor functional status at one year may improve at two years.[18]

Complications

Overall, 20% of patients develop focal deficits or die from the anti NMDAR encephalitis. Approximately 10% of patients may relapse within two years of initial presentation but usually with a less severe presentation.[13] More commonly reported long-term deficits involve attention, memory, and executive functions.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with suspected anti-NMDAR encephalitis should have a lumbar puncture and antibody testing on CSF. The initiation of immunotherapy should not delay while waiting for antibody results.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of autoimmune encephalitis are very complex and best done with an interprofessional team. The diagnosis usually requires consultation from a neurologist.

The treatment approach of immunotherapy is the prompt initiation of first-line treatment (corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulins, or plasma exchange) and escalation to second-line therapies(rituximab, cyclophosphamide) if needed. Because some patients have neuropsychiatric features, a mental health nurse should be involved in the care. The pharmacist should educate the patient and caregivers about the drugs, their adverse effects, and potential benefits, as well as performing medication reconciliation and dose verification. Nursing will provide follow-up, answer patient questions, and monitor therapeutic effectiveness as well as adverse events, reporting any issues to the treating clinician. The recovery is slow, and hence social work should be involved to ensure that the patient has adequate support services. Those who develop movement disorders may have difficulty with speech, gait, and swallowing. Long-term monitoring by the interprofessional team is vital to prevent high morbidity. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Dalmau J, Gleichman AJ, Hughes EG, Rossi JE, Peng X, Lai M, Dessain SK, Rosenfeld MR, Balice-Gordon R, Lynch DR. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: case series and analysis of the effects of antibodies. The Lancet. Neurology. 2008 Dec:7(12):1091-8. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70224-2. Epub 2008 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 18851928]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHughes EG, Peng X, Gleichman AJ, Lai M, Zhou L, Tsou R, Parsons TD, Lynch DR, Dalmau J, Balice-Gordon RJ. Cellular and synaptic mechanisms of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010 Apr 28:30(17):5866-75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0167-10.2010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20427647]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArmangue T, Spatola M, Vlagea A, Mattozzi S, Cárceles-Cordon M, Martinez-Heras E, Llufriu S, Muchart J, Erro ME, Abraira L, Moris G, Monros-Giménez L, Corral-Corral Í, Montejo C, Toledo M, Bataller L, Secondi G, Ariño H, Martínez-Hernández E, Juan M, Marcos MA, Alsina L, Saiz A, Rosenfeld MR, Graus F, Dalmau J, Spanish Herpes Simplex Encephalitis Study Group. Frequency, symptoms, risk factors, and outcomes of autoimmune encephalitis after herpes simplex encephalitis: a prospective observational study and retrospective analysis. The Lancet. Neurology. 2018 Sep:17(9):760-772. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30244-8. Epub 2018 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 30049614]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDalmau J, Armangué T, Planagumà J, Radosevic M, Mannara F, Leypoldt F, Geis C, Lancaster E, Titulaer MJ, Rosenfeld MR, Graus F. An update on anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis for neurologists and psychiatrists: mechanisms and models. The Lancet. Neurology. 2019 Nov:18(11):1045-1057. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30244-3. Epub 2019 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 31326280]

Gable MS, Sheriff H, Dalmau J, Tilley DH, Glaser CA. The frequency of autoimmune N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis surpasses that of individual viral etiologies in young individuals enrolled in the California Encephalitis Project. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2012 Apr:54(7):899-904. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir1038. Epub 2012 Jan 26 [PubMed PMID: 22281844]

van Coevorden-Hameete MH, Titulaer MJ, Schreurs MW, de Graaff E, Sillevis Smitt PA, Hoogenraad CC. Detection and Characterization of Autoantibodies to Neuronal Cell-Surface Antigens in the Central Nervous System. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience. 2016:9():37. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2016.00037. Epub 2016 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 27303263]

Iizuka T, Sakai F, Ide T, Monzen T, Yoshii S, Iigaya M, Suzuki K, Lynch DR, Suzuki N, Hata T, Dalmau J. Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis in Japan: long-term outcome without tumor removal. Neurology. 2008 Feb 12:70(7):504-11 [PubMed PMID: 17898324]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTitulaer MJ, Höftberger R, Iizuka T, Leypoldt F, McCracken L, Cellucci T, Benson LA, Shu H, Irioka T, Hirano M, Singh G, Cobo Calvo A, Kaida K, Morales PS, Wirtz PW, Yamamoto T, Reindl M, Rosenfeld MR, Graus F, Saiz A, Dalmau J. Overlapping demyelinating syndromes and anti–N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis. Annals of neurology. 2014 Mar:75(3):411-28 [PubMed PMID: 24700511]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIizuka T, Kaneko J, Tominaga N, Someko H, Nakamura M, Ishima D, Kitamura E, Masuda R, Oguni E, Yanagisawa T, Kanazawa N, Dalmau J, Nishiyama K. Association of Progressive Cerebellar Atrophy With Long-term Outcome in Patients With Anti-N-Methyl-d-Aspartate Receptor Encephalitis. JAMA neurology. 2016 Jun 1:73(6):706-13. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0232. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27111481]

Lagarde S, Lepine A, Caietta E, Pelletier F, Boucraut J, Chabrol B, Milh M, Guedj E. Cerebral (18)FluoroDeoxy-Glucose Positron Emission Tomography in paediatric anti N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis: A case series. Brain & development. 2016 May:38(5):461-70. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2015.10.013. Epub 2015 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 26542469]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStaley EM, Jamy R, Phan AQ, Figge DA, Pham HP. N-Methyl-d-aspartate Receptor Antibody Encephalitis: A Concise Review of the Disorder, Diagnosis, and Management. ACS chemical neuroscience. 2019 Jan 16:10(1):132-142. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00304. Epub 2018 Aug 31 [PubMed PMID: 30134661]

Breese EH, Dalmau J, Lennon VA, Apiwattanakul M, Sokol DK. Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis: early treatment is beneficial. Pediatric neurology. 2010 Mar:42(3):213-4. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.10.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20159432]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTitulaer MJ, McCracken L, Gabilondo I, Armangué T, Glaser C, Iizuka T, Honig LS, Benseler SM, Kawachi I, Martinez-Hernandez E, Aguilar E, Gresa-Arribas N, Ryan-Florance N, Torrents A, Saiz A, Rosenfeld MR, Balice-Gordon R, Graus F, Dalmau J. Treatment and prognostic factors for long-term outcome in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: an observational cohort study. The Lancet. Neurology. 2013 Feb:12(2):157-65. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70310-1. Epub 2013 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 23290630]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZhang L, Wu MQ, Hao ZL, Chiang SM, Shuang K, Lin MT, Chi XS, Fang JJ, Zhou D, Li JM. Clinical characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor encephalitis: A systematic review of reported cases. Epilepsy & behavior : E&B. 2017 Mar:68():57-65. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.12.019. Epub 2017 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 28109991]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencede Bruijn MAAM, van Sonderen A, van Coevorden-Hameete MH, Bastiaansen AEM, Schreurs MWJ, Rouhl RPW, van Donselaar CA, Majoie MHJM, Neuteboom RF, Sillevis Smitt PAE, Thijs RD, Titulaer MJ. Evaluation of seizure treatment in anti-LGI1, anti-NMDAR, and anti-GABA(B)R encephalitis. Neurology. 2019 May 7:92(19):e2185-e2196. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007475. Epub 2019 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 30979857]

Wang HY, Li T, Li XL, Zhang XX, Yan ZR, Xu Y. Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis mimics neuroleptic malignant syndrome: case report and literature review. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. 2019:15():773-778. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S195706. Epub 2019 Apr 2 [PubMed PMID: 31040676]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNeyens RR, Gaskill GE, Chalela JA. Critical Care Management of Anti-N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptor Encephalitis. Critical care medicine. 2018 Sep:46(9):1514-1521. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003268. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29927776]

Balu R, McCracken L, Lancaster E, Graus F, Dalmau J, Titulaer MJ. A score that predicts 1-year functional status in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. Neurology. 2019 Jan 15:92(3):e244-e252. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006783. Epub 2018 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 30578370]