Introduction

The word "anemia" derives from an ancient Greek word anaimia, meaning "lack of blood."

Anemia, like a fever, is not a diagnosis but a presentation of an underlying disease. Multiple diseases can present as anemia due to various mechanisms.

Anemia affects a significant number of people worldwide (more so in the developing world), resulting in a considerable increase in the cost of medical care.

Anemia can be defined as a reduction in hemoglobin (less than 13.5 g/dL in men; less than 12.0 g/dL in women) or hematocrit (less than 41.0% in men; less than 36.0% in women) or red blood cell (RBC) count. The terms hemoglobin and hematocrit are more commonly used than RBC count in day-to-day clinical practice. There are different lower limits of normal range based on ethnicity, gender, and age.

Anemia causes decreased oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood leading to tissue hypoxia.

Grading of anemia, according to the National Cancer Institute, is as follows:

- Mild: Hemoglobin 10.0 g/dL to lower limit of normal

- Moderate: Hemoglobin 8.0 to 10.0 g/dL

- Severe: Hemoglobin 6.5 to 7.9 g/dL[1]

- Life-threatening: Hemoglobin less than 6.5 g/dL

Anemia is classified into acute anemia and chronic anemia. Acute anemia is predominantly due to acute blood loss or acute hemolysis. Chronic anemia is more common and is secondary to multiple causes.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of chronic anemia is based on mean corpuscular volume (MCV). MCV is the average size of RBC.

Microcytic anemia (MCV less than 80 femtoliters [fL])

- Iron deficiency anemia: Most common cause of anemia

- Thalassemia

- Anemia of chronic disease

- Sideroblastic anemia

Macrocytic Anemia (MCV greater than 100 fL)

- Vitamin B12 and folic acid deficiency

- Alcoholism and liver disease

- Myelodysplastic syndromes

- Drug-induced

- Hypothyroidism

Normocytic anemia (MCV 80 to 100 fL)

- Bone marrow suppression (aplastic anemia and myelophthisic anemia)

- Anemia of chronic disease

Hemolytic anemia

Hemolytic anemia may be due to hemolytic uremic syndrome, sickle cell, mechanical heart valves, disseminated intravascular coagulation, cold hemoglobinuria, and cold agglutinin disease.

Some conditions can present in more than one classification. For example, early iron deficiency can be normocytic. Anemia of chronic disease is mostly normocytic but can be microcytic too. Hemolytic anemia can cause either macrocytic or normocytic anemia.[2][2]

Epidemiology

Iron deficiency anemia is the most common type of anemia, affecting approximately 8% to 9% of the world’s population.

Anemia is more prevalent in:

- Developing countries due to malnutrition and lack of proper medical care

- Women due to pregnancy and menstrual bleeding [3]

- African Americans due to sickle cell disease and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency

- Older adults, due to multiple comorbidities like chronic kidney disease (CKD), malignancy, medications, among others.[4]

Pathophysiology

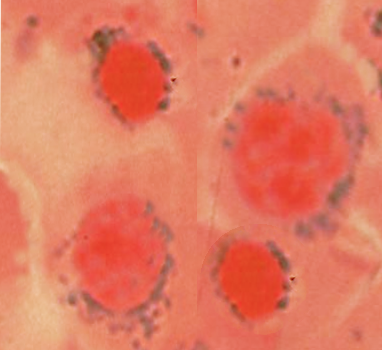

Erythropoiesis

Red blood cells are produced in bone marrow with the help of nutrients (iron, B12, folic acid), cytokines, erythroid-specific GF, and EPO (erythropoietin, produced by kidneys). Once RBCs are released into the blood, they have a lifespan of about 110 to 120 days. Approximately 1% of RBCs are removed every day from the circulation. Under normal conditions, there is a balance between the number of RBCs released into circulation by the bone marrow to the number removed from circulation. Imbalance of production and release by the bone marrow to loss of RBC leads to anemia as below.

Decreased Red Blood Cell Production

- Lack of nutrients (malnutrition and malabsorption)

- Bone marrow problems (suppression and lack of RBC precursors)

- Lack of hormones (CKD, hypothyroidism)

- Ineffective erythropoiesis (defective RBC production)

Increased Red Blood Cell Destruction (Hemolytic Anemia)

Inherited hemolytic anemia

- Sickle cell anemia

- Thalassemia

- Hereditary spherocytosis and elliptocytosis

- G6PD deficiency

- Pyruvate kinase deficiency

Acquired hemolytic anemia

- Immune hemolytic anemia

- Mechanical hemolytic anemia

- Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

Blood Loss

- Gastrointestinal

- Menstrual cycles (menorrhagia)

- Surgery

- Trauma

Some conditions can cause anemia by over one mechanism (two or even all the three mechanisms).

Anemia of chronic disease is a common form of anemia seen in hospitalized patients caused by long-standing diseases, infections, inflammations, and malignancies. These chronic conditions cause increased production of hepcidin[5] by the liver. Hepcidin binds to its receptor ferroportin and decreases intestinal iron absorption and decreases the release of iron from liver and macrophages, leading to decreased availability of iron for erythropoiesis. Other mechanisms that contribute to anemia are by inflammatory cytokines that increase red cell destruction, suppress the proliferation of erythroid precursors, and by inhibiting the release of erythropoietin from kidneys.

CKD [6] is one of the common causes of anemia of chronic disease. The incidence of anemia increases with the progression of CKD, especially from stage III to stage IV and stage V. Erythropoietin is an important hormone needed for erythropoiesis. Anemia causes tissue hypoxia, which, in turn, stimulates erythropoietin production by kidneys. Kidneys produce about 90% of the total erythropoietin, and as CKD progress, its response to hypoxia decreases, causing low erythropoietin levels leading to anemia. CKD can also cause anemia from hemolysis.

History and Physical

Symptoms and signs of chronic anemia are mostly due to decreased tissue oxygenation from the reduction of the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood. Symptoms are worse when anemia is severe, with a rapid decrease in hemoglobin and hematocrit and with increased oxygen demand states like exercise.

Common presenting symptoms include:

- Weakness, fatigue

- Dizziness, near syncope, syncope

- Exertional dyspnea (exercise intolerance)

- Chest pain and palpitations

- Anorexia

- Cognitive impairment in elderly[7]

A detailed history should include medical history, home medications, alcohol use, and family history. Ethnicity and country of origin are also helpful.

Important examination findings include:

- Pallor

- Jaundice

- Tachycardia

- Tachypnea

- Orthostatic hypotension and

- Other findings relevant to underlying etiology

Evaluation

Initial work-up

- Complete blood count: Hemoglobin, hematocrit (HCT), MCV, reticulocyte count index

- Comprehensive metabolic panel: Renal and liver function tests

- Iron studies which include serum iron, TIBC (total iron-binding capacity) and ferritin

- Serum vitamin B12, folic acid, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

- Stool for occult blood

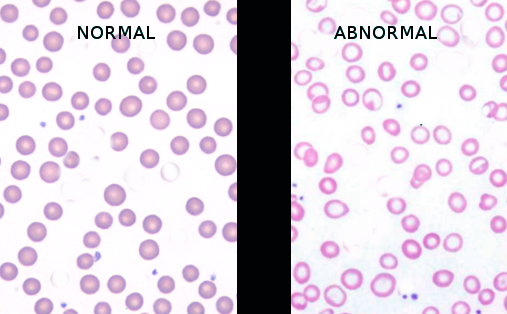

Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) is a measure of the volume occupied by a single red blood cell. Increased values are seen in macrocytic anemia (vitamin B12 deficiency, folate deficiency, alcohol use), whereas decreased values are seen in microcytic anemia.

Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration reflects the average hemoglobin concentration in RBCs. Increased values are seen in spherocytosis, and low values are seen in thalassemia, iron deficiency, and macrocytic anemia.

The reticulocyte count reflects the presence of nonnucleated immature red blood cells in the bone marrow. Increased levels are seen when there is accelerated erythropoiesis, following anemia, hemorrhage, pregnancy, or splenectomy. Decreased levels indicate lower production and can be a result of aplastic anemia, radiation exposure, or chronic infection.

Differentiation of microcytic anemias based on iron studies

- Iron deficiency anemia: Low serum iron, high TIBC, and low ferritin.

- Anemia of chronic disease: Low serum iron, low TIBC, and high ferritin.

- Sideroblastic anemia: High serum iron, normal TIBC, and high ferritin.

- Thalassemia: Normal serum iron, normal TIBC, and normal ferritin.

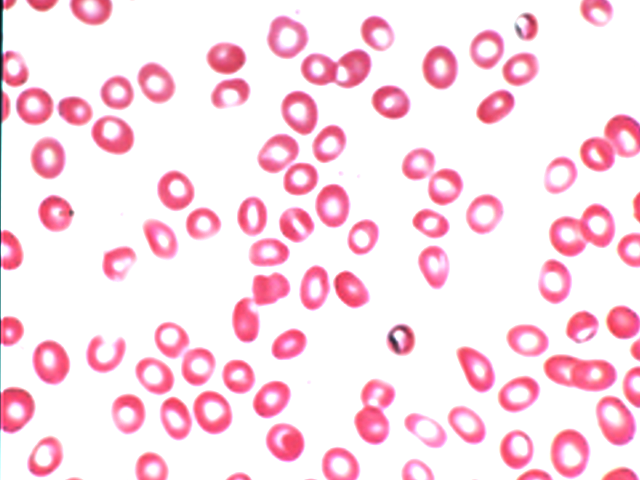

Peripheral smear, hemoglobin electrophoresis, and bone marrow examination if needed. Further testing would include esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy if gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is suspected and imaging studies if malignancy is suspected.

Treatment / Management

Chronic anemia is managed predominantly in outpatient settings. They need hospitalization if:

- Patient is symptomatic

- There is a significant drop in hemoglobin/HCT

- Transfusion is needed

- Extensive investigations are needed

If hemoglobin is less than 7 g/dL or if a patent is symptomatic, transfusion of packed red blood cells (PRBC) are indicated.

Transfusions should be performed with caution in patients with volume overload status like end-stage renal disease (on hemodialysis) and congestive heart failure (CHF).

Other treatments include treating underlying conditions as below.

- Iron deficiency anemia: Intravenous (IV) iron versus oral iron

- Vitamin B12 and folic acid deficiency with B12 and folic acid supplementation

- Treating underlying bone marrow disorders

- EPO injections in chronic kidney disease patients

- Synthroid in patients with hypothyroidism

- Avoiding any culprit medications

- Treatment of GI causes of blood loss (PPI for gastritis and PUD)

- Regulation of menstrual cycles in patients with menorrhagia

Admission if:

- The patient has acute bleeding with hypovolemia, tachycardia and altered mental status

- Presence of pancytopenia

- Non-compliant patients or those who require extensive workup

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of chronic anemia is as follows:

- Renal failure

- Myxedema coma

- Adrenal crisis

- Tuberculosis

- HIV

Prognosis

Prognosis of anemia varies based on the cause of anemia. Other factors contributing to the prognosis include:

- Age of the patient

- Severity of anemia

- Duration of anemia

- Comorbidities

- Access to medical care

- Diet

Elderly patients have a poor prognosis due to their advanced age, malnutrition, and multiple comorbidities they tend to have as they age. Patients in the developing world also have a poor prognosis due to malnutrition and lack of access to or delayed medical care.

Hemoglobin less than 6.5 g/dL is life-threatening and can cause death.

Complications

Untreated anemia can be life-threatening and can even cause death.

Anemia results in a decreased oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood. In the short term, the body can compensate with an increase in heart rate and respiratory rate. If left untreated, anemia can cause multi-organ failure. This can include high output heart failure, angina, arrhythmias, cognitive impairment, and renal failure, among others. In pregnant women, untreated anemia can cause premature birth and low birth weight.

Consultations

- Gastroenterology if GI bleeding suspected

- Nephrology in patients with chronic kidney disease

- Hematology if bone marrow disease or hemolysis is suspected

- Obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN) for menorrhagia

Deterrence and Patient Education

Anemia is a condition with a decreased oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood. Anemia is very common and caused by different conditions ranging from simple nutritional deficiencies (iron, vitamin B12, and folic acid), blood loss, or other complicated causes.

Anemia is a common medical condition and easily diagnosed with complete blood count. Treatment can range from nutritional supplements (iron, vitamin B12, and folic acid) to blood transfusion to treating complex underlying conditions.

It is very important to follow up with the provider and sometimes with a specialist to treat anemia because untreated anemia can be life-threatening and may even cause death.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Anemia is the most common hematological disorder and is one of the most common conditions seen in clinical practice.

- Iron deficiency anemia is the most common cause of anemia, while anemia of chronic disease is the most common anemia in hospitalized patients.

- Anemia is not a diagnosis but a presentation of underlying diseases. Work up for the cause of anemia can unmask many of the underlying diseases, thereby helping to treat patients early and appropriately.

- Most of the anemias are easy to treat and thereby improve a person's productivity.

- Comprehensive history taking and physical examination are very important in diagnosing anemia.

- If early workup is unrevealing, appropriate consultation by a specialist is important for further workup and treatment.

- Encouraging patients to eat a healthy and balanced diet is important to prevent anemia due to nutritional deficiencies.

- Women of childbearing age are at increased risk of anemia due to pregnancies and menstrual bleeding and need close monitoring.[8][9]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Chronic anemia is a very common condition seen in day-to-day clinical practice and managed in outpatient settings. Because of numerous causes, the disorder is best managed by an interprofessional team. Anemia management can range from simple to complex based on the underlying condition causing it.

The patient's primary care physician and nurse practitioner may need the help of a specialist based on the underlying condition, either a gastroenterologist, hematologist, nephrologist, or gynecologist.

Any pharmaceutical interventions should have consult from a pharmacist, perhaps even a board-certified pharmacotherapy specialist, who can better guide drug interventions and assist the clinician staff. The social worker should be involved, as some patients may neglect treatment due to a lack of finances. Once the anemia is treated, the primary clinicians need to observe the patient for signs and symptoms of recurrent anemia. The dietitian should educate the patient on eating a healthy diet that consists of fruits and vegetables. The pharmacist should encourage abstinence from alcohol. At every discharge, the nurse should educate the patients on the importance of follow up with the relevant specialists.

It is very important to have good interprofessional communication and care coordination for the management of anemia appropriately and promptly. This will prove invaluable in correcting anemia and treating the underlying conditions.

The outcomes of chronic anemia depend on the cause, chronicity, other comorbidities, and the presence of malignancy. [Level 5]

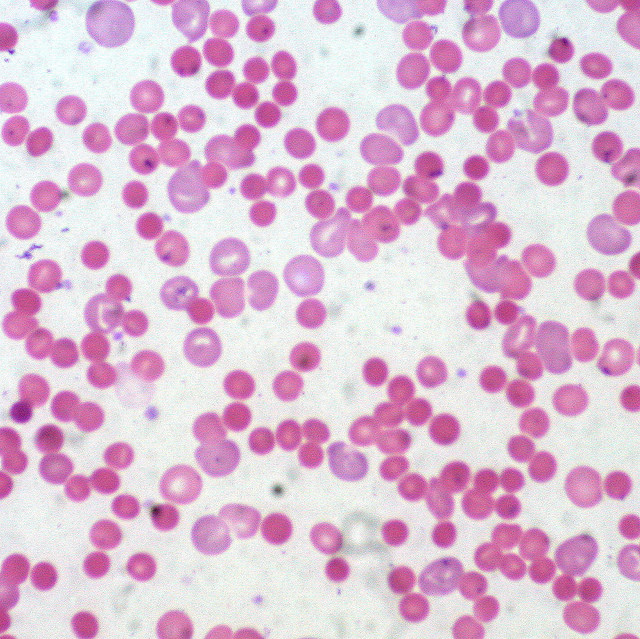

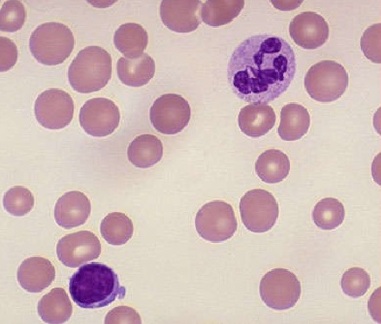

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Tas F, Eralp Y, Basaran M, Sakar B, Alici S, Argon A, Bulutlar G, Camlica H, Aydiner A, Topuz E. Anemia in oncology practice: relation to diseases and their therapies. American journal of clinical oncology. 2002 Aug:25(4):371-9 [PubMed PMID: 12151968]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSachdev V, Rosing DR, Thein SL. Cardiovascular complications of sickle cell disease. Trends in cardiovascular medicine. 2021 Apr:31(3):187-193. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2020.02.002. Epub 2020 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 32139143]

Baradwan S, Alyousef A, Turkistani A. Associations between iron deficiency anemia and clinical features among pregnant women: a prospective cohort study. Journal of blood medicine. 2018:9():163-169. doi: 10.2147/JBM.S175267. Epub 2018 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 30323700]

Lanier JB, Park JJ, Callahan RC. Anemia in Older Adults. American family physician. 2018 Oct 1:98(7):437-442 [PubMed PMID: 30252420]

Kunireddy N, Jacob R, Khan SA, Yadagiri B, Sai Baba KSS, Rajendra Vara Prasad I, Mohan IK. Hepcidin and Ferritin: Important Mediators in Inflammation Associated Anemia in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients. Indian journal of clinical biochemistry : IJCB. 2018 Oct:33(4):406-413. doi: 10.1007/s12291-017-0702-1. Epub 2017 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 30319186]

Anand S,Thomas B,Remuzzi G,Riella M,Nahas ME,Naicker S,Dirks J, Kidney Disease null. 2017 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 30212067]

Hong CT, Hsieh YC, Liu HY, Chiou HY, Chien LN. Association Between Anemia and Dementia: A Nationwide, Populationbased Cohort Study in Taiwan. Current Alzheimer research. 2020:17(2):196-204. doi: 10.2174/1567205017666200317101516. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32183675]

Agbozo F, Abubakari A, Der J, Jahn A. Maternal Dietary Intakes, Red Blood Cell Indices and Risk for Anemia in the First, Second and Third Trimesters of Pregnancy and at Predelivery. Nutrients. 2020 Mar 15:12(3):. doi: 10.3390/nu12030777. Epub 2020 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 32183478]

Ray JG, Davidson A, Berger H, Dayan N, Park AL. Haemoglobin levels in early pregnancy and severe maternal morbidity: population-based cohort study. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2020 Aug:127(9):1154-1164. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16216. Epub 2020 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 32175668]