Introduction

When conventional wound closure methods, whether for cosmetic or functional reasons, prove impractical, the need arises for additional tissue reconstruction. This necessitates the use of grafts or flaps. Grafts, like split-thickness skin or mucosal grafts, serve as non-vascularized tissue patches. In contrast, flaps are vascularized, contributing to high success rates in healing. Flaps can originate from distant body sites, requiring microsurgical blood vessel anastomosis near the wound site, earning them the label microvascular "free" flaps. "Regional" flaps involve tissue transfer from non-adjacent areas without such microsurgical connections, while "local" flaps move tissue immediately neighboring the primary defect. Local flaps are further classified into transposition, rotation, advancement, and interpolation, with the latter sometimes categorized as a hallmark of regional flaps by different authors.[1][2][3] Advancement flaps are conceptually the simplest local flaps and, along with rotation flaps, are sometimes known as "sliding" flaps.[4][5][6] For sliding flaps, the tissue is moved or "slid" directly into the adjacent defect without crossing over or under normal tissue, as is seen in transposition and interpolated flaps.

Local flap advancement is a versatile cornerstone in cutaneous surgery for several compelling reasons. Firstly, these flaps boast a straightforward conceptual framework, demanding far less spatial reasoning or geometric finesse in their design compared to transposition flaps like z-plasties and bilobed flaps.[7][8] Secondly, they possess the distinct advantage of not leaving secondary defects that necessitate subsequent closure at the flap's initial elevation or harvesting site, a challenge common to transposition, interpolated, regional, and free flaps. Moreover, tissue advancement techniques find utility beyond wound closure scenarios. For instance, V to Y advancement aids in lengthening the columella of the nose in cleft lip cases, restoring the position of the lobule in post-rhytidectomy pixie ear deformities, correcting partial syndactyly, and releasing scar bands that distort anatomical structures such as the eyelid. Furthermore, these techniques extend their utility to cosmetic or gender-affirming procedures like lowering the hairline with scalp advancement and forming the basis of facelift surgery through cheek advancement.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

While planning flap reconstructions demands meticulous consideration of each defect's unique anatomical characteristics, the foremost concern invariably revolves around the flap's vascular supply. Flaps may be classified based on their proximity to the primary defect or the type of tissue movement required. Still, from an anatomical perspective, their categorization hinges on their vascular supply. Regional and free flaps fall under the category of "axial" flaps, denoting the presence of a named vessel typically coursing the length of the flap. Consequently, when designing these flaps, there are no strict guidelines concerning length-to-width ratios as long as the tissue incorporated within the flap receives perfusion from the vessel or vessels delivering blood to the flap. Whether these vessels remain intact throughout the procedure or are anastomosed with other vessels closer to the defect after flap transfer, preserving the integrity of the vascular pedicle (the tissue stalk containing the vessels entering and exiting the flap) holds paramount importance for axial flaps. This emphasis arises because axial flaps generally encompass tissue from a single angiosome, meaning a solitary artery can perfuse all the tissue within the flap. Conversely, local flaps, such as advancement flaps, typically rely on "random" blood supplies. In this context, perfusion doesn't arrive via a designated vessel but instead through the microvasculature of the subdermal plexus at the flap's base, which remains connected to the donor site tissue.

Given the subdermal vasculature's small caliber, irregular configuration, and lower perfusion pressure, the meticulous design of advancement flaps is crucial. It's recommended that on the face, the length-to-width ratio should not exceed 3:1, while on the trunk and extremities, it should stay within 2:1.[9] Deviating from these proportions risks compromising perfusion, potentially leading to tissue loss, often at the flap's distal aspect. Patients with vasculopathy, notably tobacco users and those who've undergone radiotherapy, tend to fare better with axially perfused flaps due to their more reliable blood supply. However, even random-perfusion flaps generally outperform free skin grafts.

When local flaps are employed on the face, camouflage of the scars should be another significant consideration for the surgeon. The face is made up of 8 aesthetic units (forehead, nose, 2 periorbital areas, 2 cheeks, perioral area, and chin), each of which contains several subunits (eg, the nose contains 9: dorsum, tip, columella, 2 sidewalls, 2 alae, and 2 soft tissue facets). Placing incisions into the junctions between these will often hide surgical scars very effectively. Scars may also be hidden in facial wrinkles when they are present. Wrinkles, scientifically known as rhytides, primarily develop due to the influence of underlying mimetic muscles, although solar damage can also contribute. Rhytides stemming from muscle activity follow predictable patterns and align with "relaxed skin tension lines." These lines run perpendicular to the underlying muscle's contraction vector. Conversely, "lines of maximum extensibility" run parallel to the muscle's contraction direction, indicating the most effective stretching vectors for flaps. The efficacy of skin stretching for defect reconstruction can be further enhanced by leveraging "stress relaxation," where progressively less tension is needed to sustain a specific stretch length in a flap, and "skin creep," the skin's ability to lengthen under continuous tension.

Indications

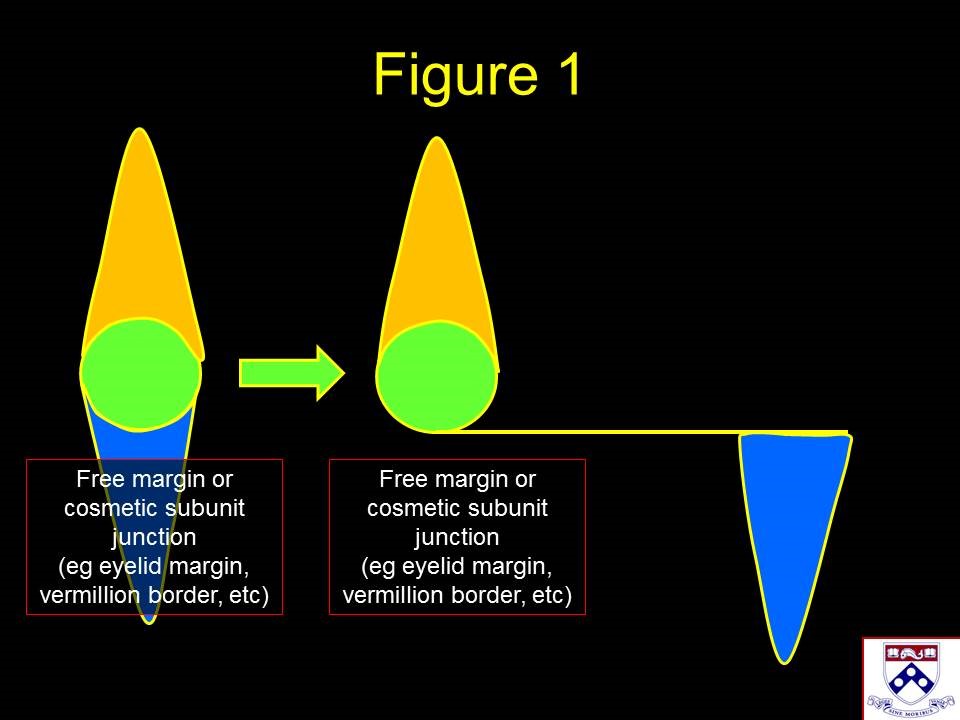

Advancement flaps are modified linear closures where one or both apical standing cones are moved to the side. When a free margin, such as the eyelid, lip, or alar rim, or a cosmetic subunit junction, such as the nasolabial fold or orbitomalar groove, would be violated by a linear closure, advancement flaps may be utilized to direct the incisions or standing cones away from these natural boundaries (see Image. Standing Cone Redirection Using Advancement Flaps). Advancement flaps often camouflage scars by placing incision lines along natural creases or cosmetic subunit junctions. In some cases, advancement flaps may be used to rearrange tissue rather than to close a wound; examples include facelifting and hairline lowering. Common locations for advancement flap wound closures include the upper and lower cutaneous lip, the nasal dorsum, the cheek, the lower eyelid, the forehead, and the helical rim.[10][11][12]

Contraindications

Patients with wounds exceeding the capacity for closure via adjacent tissue must explore reconstructive methods using distant tissue sources. These include skin and mucosal grafts, regional interpolated flaps, and free microvascular tissue transfer. Moreover, when scarring, infection, inflammation, or prior radiation impedes the advancement of healthy tissue around the wound, exploring alternative vascularized tissue transfer options becomes imperative.

Notably, a recent smoking history is a relative contraindication for advancement flap use. While cutaneous microvasculature typically returns to nearly normal function after a 2-week smoking cessation, caution is advised in flap surgeries involving habitual tobacco users.[13][14]

Equipment

- Local anesthetic (1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine or similar)

- Hypodermic syringe and needle

- Skin prep solution (5-10% povidone-iodine, 4% chlorhexidine gluconate, or 70% isopropyl alcohol)

- Skin marker

- Measuring tape or calipers

- Scalpel (#15, #15c, or #11 blade, or #6700 beaver blade)

- Adson-Brown or 0.5 mm Castroviejo forceps

- Kaye blepharoplasty, iris, or Westcott scissors

- Halsey or Castroviejo needle driver

- Joseph or Guthrie double-prong hooks

- Bipolar electrocautery forceps

- Monopolar electrocautery pencil

- Suture scissors (iris, tenotomy, or Mayo)

- Skin sutures, such as 6-0 polypropylene

- Deep dermal suture, such as 5-0 poliglecaprone

- Topical antibiotic ointment (bacitracin or mupirocin)

- Dressing supplies as necessary

Personnel

Local flap advancement is a surgical procedure usually performed under local anesthesia by a surgeon and a single assistant. However, general anesthesia, which requires an anesthesia provider, may be necessary for more complex or more extensive reconstructive surgeries. General anesthesia is typically administered in an operating room, where the healthcare team includes a circulating nurse and a surgical scrub technician.

Preparation

Preoperative Preparation

The surgical site is cleansed with a solution of the surgeon's choice, and typically, a sterile field is created. For cutaneous surgery, postoperative infection rates are low at baseline, and there is little difference between proceeding under truly sterile or simply "clean" conditions.[15]

Patient Counseling

As with any reconstructive procedure, setting realistic expectations before surgery helps patients prepare for recovery and healing. Beyond typical counseling regarding pain, infection, bruising, swelling, bleeding, scar formation, damage to adjacent anatomical structures, need for additional procedures, and cosmetic dissatisfaction, a few unique situations warrant further discussion. Advancement flaps on the lower eyelid are occasionally complicated by prolonged postoperative swelling that may take months to resolve completely. Also, incision lines that fall along natural grooves or creases camouflage well in the long run but may be noticeable in the early postoperative period if the wound edges are everted. Patience and occasional use of intralesional corticosteroid injections usually correct eversion and other minor postoperative contour irregularities.

Technique or Treatment

Flap Elevation

In most instances, local flaps are meticulously raised within a subcutaneous plane, preserving the crucial blood supply from the subdermal plexus, a strategy that enhances flap viability. This subcutaneous elevation also minimizes excess tissue within the flap, optimizing its potential for stretching and pivoting, should the need arise. However, on the nasal dorsum, surgical preferences may vary; some surgeons favor a subdermal plane, while others opt for a submuscular/supraperichondrial plane, particularly when working near the nasal tip. The choice depends on factors like the sebaceous nature of the skin on the nasal tip and alae, with some surgeons favoring a muscle-inclusive flap for its robust blood supply despite potential alterations in muscle fiber orientation that might impact nasal valve patency and breathing.

Similarly, when dealing with local flaps in the scalp, the classic approach involves raising them in a submuscular/subgaleal plane, a relatively avascular layer that facilitates dissection. However, this plane encompasses the galea aponeurotica, an inelastic fascial layer resistant to stretching. On the other hand, elevating the scalp in a subcutaneous plane while potentially involving a bloodier dissection due to larger-caliber vessels traversing the galea to supply the subdermal plexus offers greater flap flexibility for stretching and rotation to fill defects.

Nonetheless, it's crucial to exercise caution and avoid overstretching or narrowing the flap, as it can lead to vascular insufficiency. For flaps in the head and neck, it's advisable to adhere to a length-to-width ratio not exceeding 3:1, while flaps in the torso or extremities should maintain a 2:1 ratio. Supplementary adjustments of surrounding tissue to complement the flap can mitigate the need for excessive stretching. This is best accomplished by undermining in the same plane as the flap for 2 to 4 cm around the defect. It's important to note that undermining beyond this extent doesn't further reduce closing tension and may even exacerbate it.[16]

Tension Vector

Advancement of the flap toward the defect is called the primary tissue motion, and the countermovement of the surrounding tissue to meet the flap is considered secondary tissue motion. As opposed to rotation and transposition flaps, advancement flaps do not significantly alter the direction or magnitude of the primary tension vector for wound closure. The site of maximal tension and the magnitude of the tension vector required to inset an advancement flap are nearly identical to those of a linear closure in the same location for a given defect. Occasionally, tacking sutures that anchor the flap to immobile deeper structures, such as the orbital rim periosteum, can offset some of the wound closure tension away from the defect.

Standing Cones

The standing cones created by local flaps are handled in several different ways. Generally, the entire standing cone can be moved to a point anywhere along the incision where the scar created by its removal will be optimally hidden, either in a relaxed skin tension line or along an anatomic subunit boundary, such as the hairline. Excision of a cutaneous standing cone along its base is a straightforward procedure that leaves an easily closed, wedge-shaped defect known as a "Burow triangle." Alternatively, a small standing cone or a portion of a large standing cone can be "sewn out" by carefully redistributing the excess skin along the entire incision, which is best accomplished by closing the wound with interrupted sutures that divide the incision successively by halves until closure is complete.

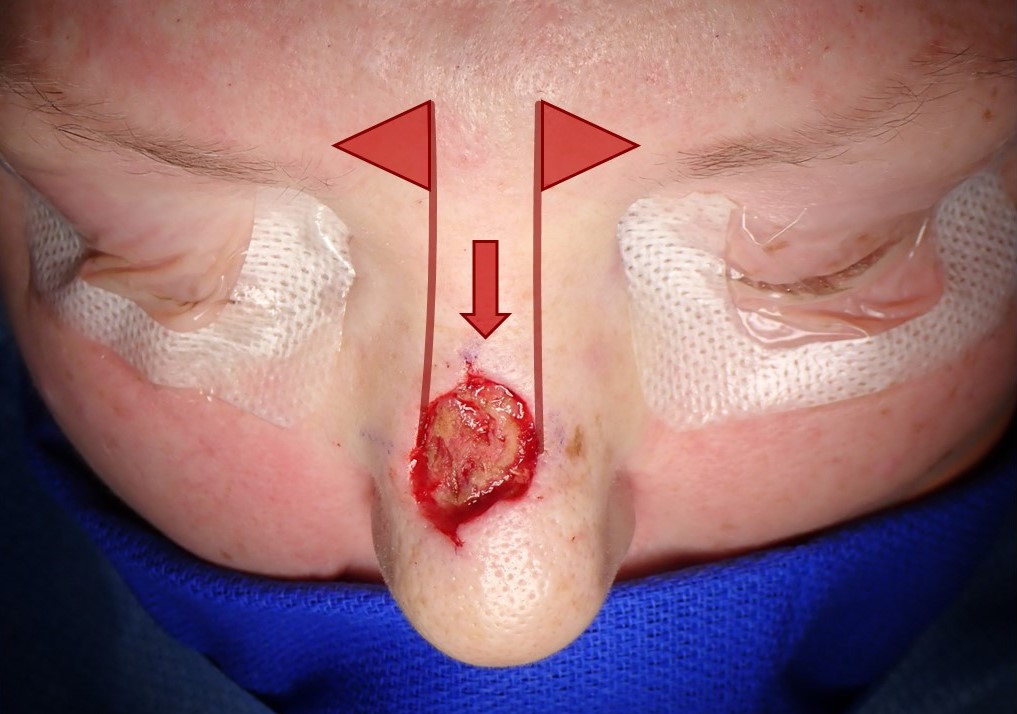

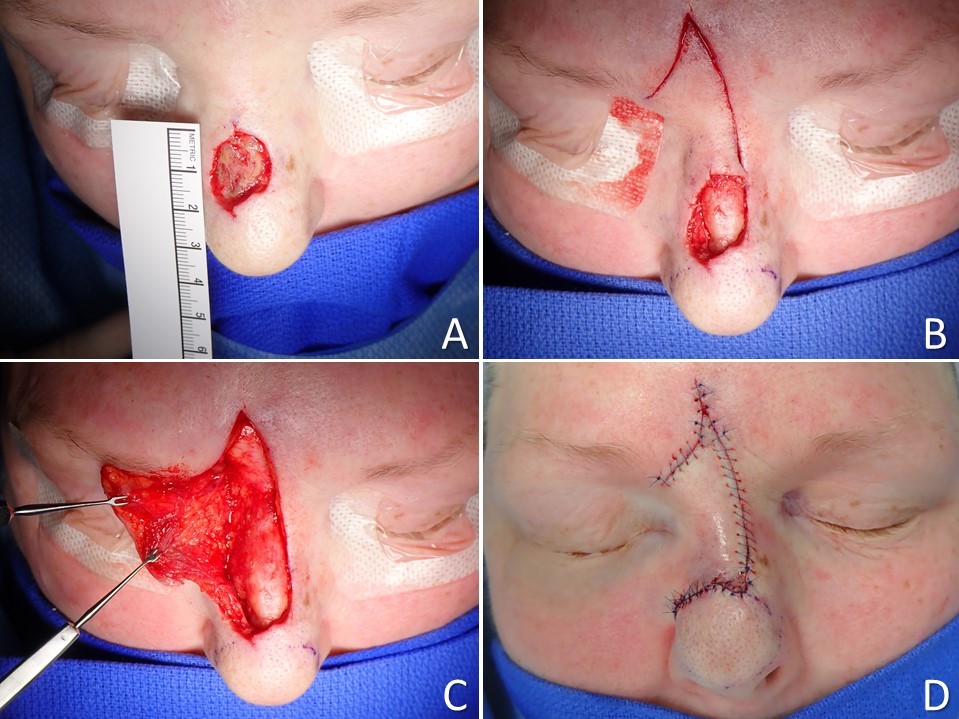

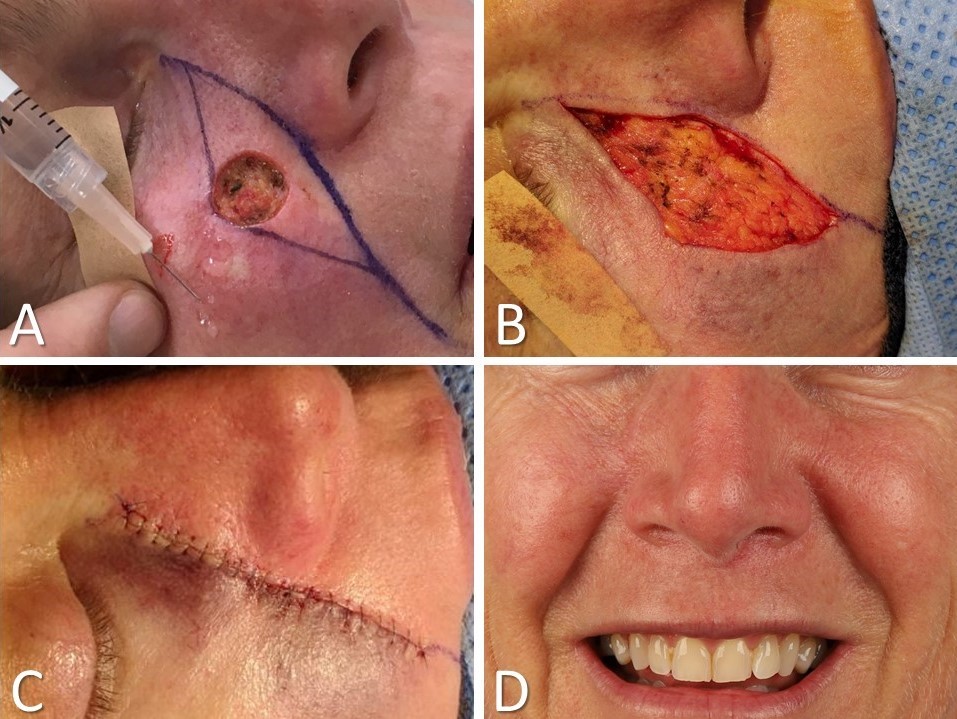

Altering the Defect to Optimize Advancement Flaps

When skin defects arise after removing a tumor, especially after Mohs surgery, a primary consideration is whether the surgeon should deepen the defect to a uniform anatomic depth. While it may seem counterintuitive to remove more tissue to facilitate closure, deepening the defect to a level corresponding to the anatomic plane for undermining ensures that the tissue advancing into the wound matches the thickness of the defect, thereby preventing a contour irregularity. While not always necessary or preferred, excising tissue between the surgical defect and a nearby cosmetic subunit junction may also prove helpful (see Image. Cheek Advancement Flap). Placing incisions along cosmetic subunit junctions camouflages scars by hiding them in natural creases and shadows.

Specific Flap Examples

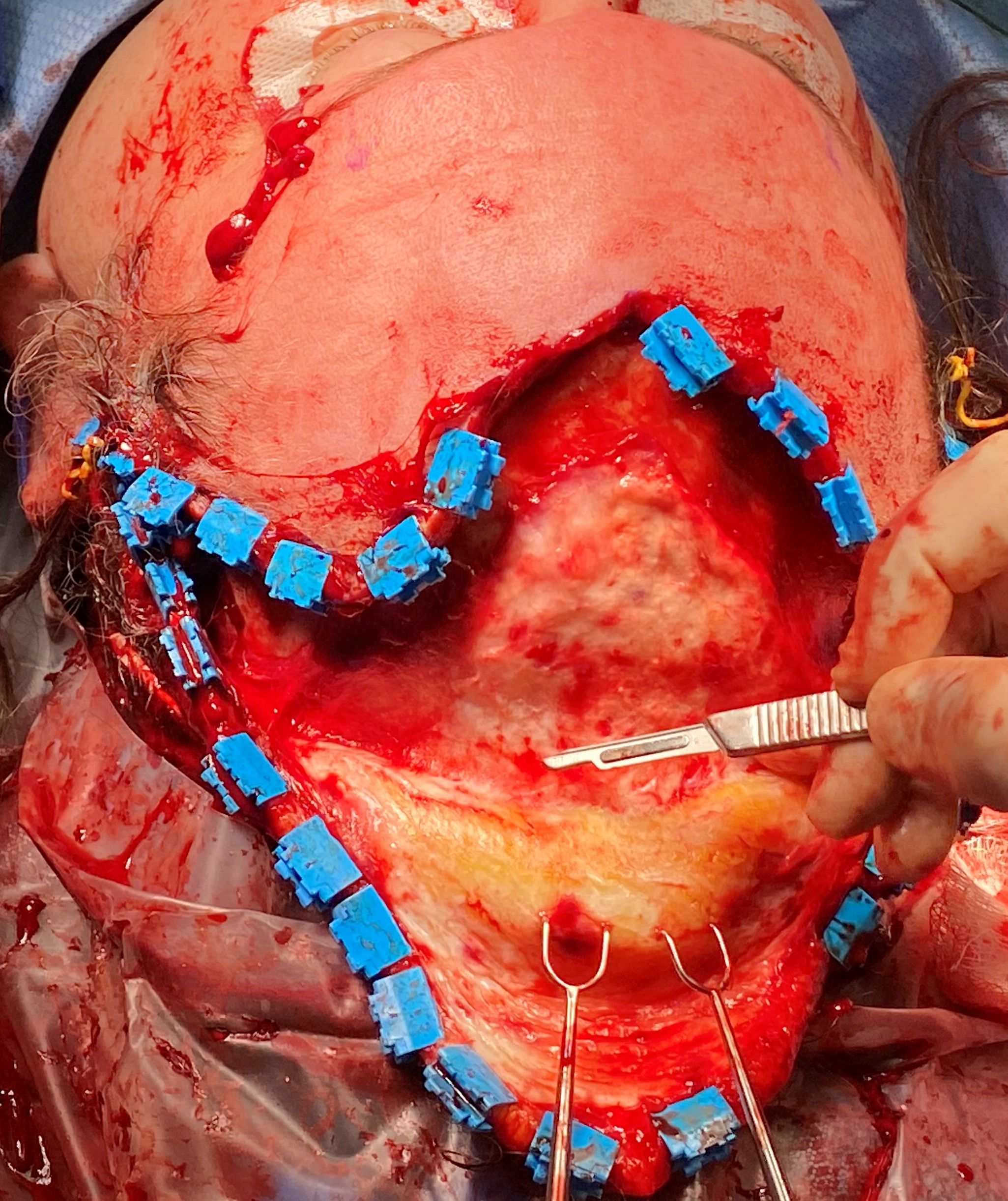

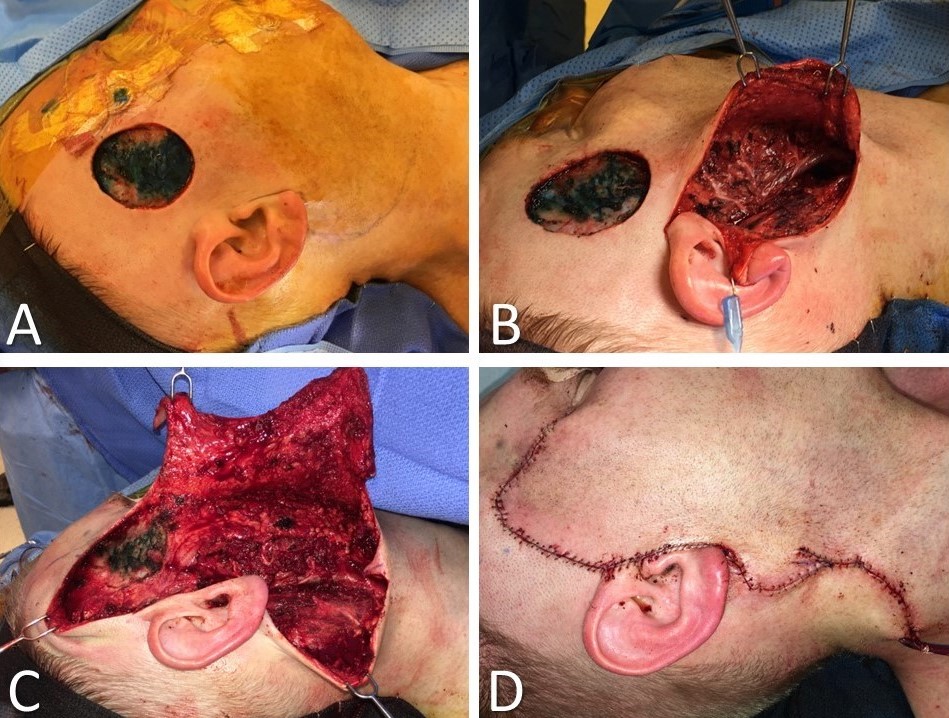

Advancement flaps exhibit remarkable diversity in their shapes and sizes, tailored to the extensive array of anatomical sites to which they are applied. While it may not be entirely accurate to claim that no 2 advancement flaps are identical, the surgeon enjoys substantial flexibility when determining an advancement flap's optimal placement and design. Intriguingly, not all advancement flaps are confined to wound closure; for instance, facelift procedures incorporate the advancement and rotation of facial flaps, mirroring the principles utilized in cervicofacial advancement flaps for reconstructive objectives (see Image. SMAS Plication Rhytidectomy and Image. Cervicofacial Advancement Flap). Moreover, scalp advancement techniques find utility in scenarios like lowering the hairline, particularly in gender affirmation surgery (see Image. Scalp Advancement Flap). Nevertheless, several frequently employed advancement flap techniques cater to specific regions of the body, each with its unique considerations and applications.

Double Advancement Flaps

When bilateral flaps are advanced to meet each other in the center of a defect, each flap has less distance to travel. An example of this concept, the O to H flap closure (also known as "H-plasty"), takes a circular defect and leaves 2 parallel scars with a shorter perpendicular scar between them, hence the technique's name. O to H advancements are most commonly used in the forehead and eyebrow region, closing wounds in such a way as to leave the longer scars within transverse forehead rhytids while avoiding any upward tension that might distort the contour of the eyebrow (see Image. O to H Bilateral Advancement Flap). A technique similar to the O to H closure is the O to T flap reconstruction, where a single releasing incision is used for each flap rather than 2 parallel ones. A single releasing incision introduces a rotation component into the flap, similar to cervicofacial flap closure (see Image. O to T Rotation Flap). This technique is also called an A to T flap reconstruction if a Burow triangle is excised from the wound.

V to Y Ddvancements

A V to Y advancement is unique because the tissue being advanced is triangular rather than rectangular. The technique is also unusual in that the tissue being advanced is pushed into place rather than being pulled or stretched to close a tissue defect. To employ a V to Y advancement, a V-shaped incision is made on the side of the tissue being advanced that is opposite the direction of advancement (see Image. V to Y Advancement). The apex of the V is then sutured together linearly until the triangle of tissue has advanced sufficiently. V to Y advancement may be performed as a simple advancement flap, in which the V-shaped flap is based opposite the V-shaped incision and is otherwise undermined and elevated, or the advancement may be performed with the flap completely circumcised and based upon a subcutaneous island that provides its blood supply. When a V to Y subcutaneous island advancement is planned, care should be taken to avoid undermining more than 60% to 70% of the island flap, or there will not be sufficient perfusion for the flap to survive. Secondary tissue movement ensures the flap reaches the primary defect without undue tension (see Image. V to Y Island Advancement Flap and Image. Reiger Dorsal Nasal Rotation-Advancement Flap). A classic application of this technique is the closure of soft tissue fingertip amputation defects. In certain cases, it may be necessary to "pull" tissue rather than "push" it; in those situations, a Y to V advancement may be performed by making a Y-shaped incision with the stem of the Y pointing in the direction of tissue movement and subsequently advancing a V-shaped flap into the stem of the Y.

Dorsal Nasal Flaps

There are numerous ways to reconstruct the nose, including rotational (Peng), transposition (bilobed), and regional interpolated flaps (paramedian forehead). However, dorsal nasal advancement flaps are excellent options for dorsal and supratip defects measuring up to 3 cm, particularly when there is minimal defect extension off the dorsal subunit into the nasal sidewall.[2][1][3][17][18] The simplest dorsal nasal flap is the Rintala flap, which is the quintessential, prototypical advancement flap. This technique inferiorly advances the dorsal nasal skin by releasing incisions between the dorsal and sidewall subunits. Burow triangles are placed bilaterally at the base of the flap, relying upon the medial edges of the brows for scar camouflage (see Image. Rintala Flap). The Rieger flap, which may be used to reconstruct the dorsum or the dorsum and one sidewall, is an advancement flap with an element of rotation around a superolateral pedicle that contains the dorsal nasal vessels, making this 1 of few local flaps that have axial rather than random blood supplies. To facilitate the flap's primary motion into the defect, the superior aspect of a Rieger flap typically incorporates a V to Y advancement (see Image. Rieger Flap). The Rieger and Rintala flaps are generally elevated in a submuscular/supraperichondrial plane, as the soft tissue envelope is elevated in an open rhinoplasty approach.[19]

Keystone Flaps

These flaps are similar to V to Y island advancement flaps in that they are entirely circumcised and receive a blood supply via the underlying subcutaneous tissue. Their trapezoidal shape allows the short parallel side of the flap to advance into a defect as the long parallel side is pushed from behind. The corners of the flap farthest from the defect undergo V to Y closure to affect the flap's primary movement (see Image. Keystone Flap). Keystone flaps are versatile and may be employed nearly anywhere, particularly in the trunk and extremities.

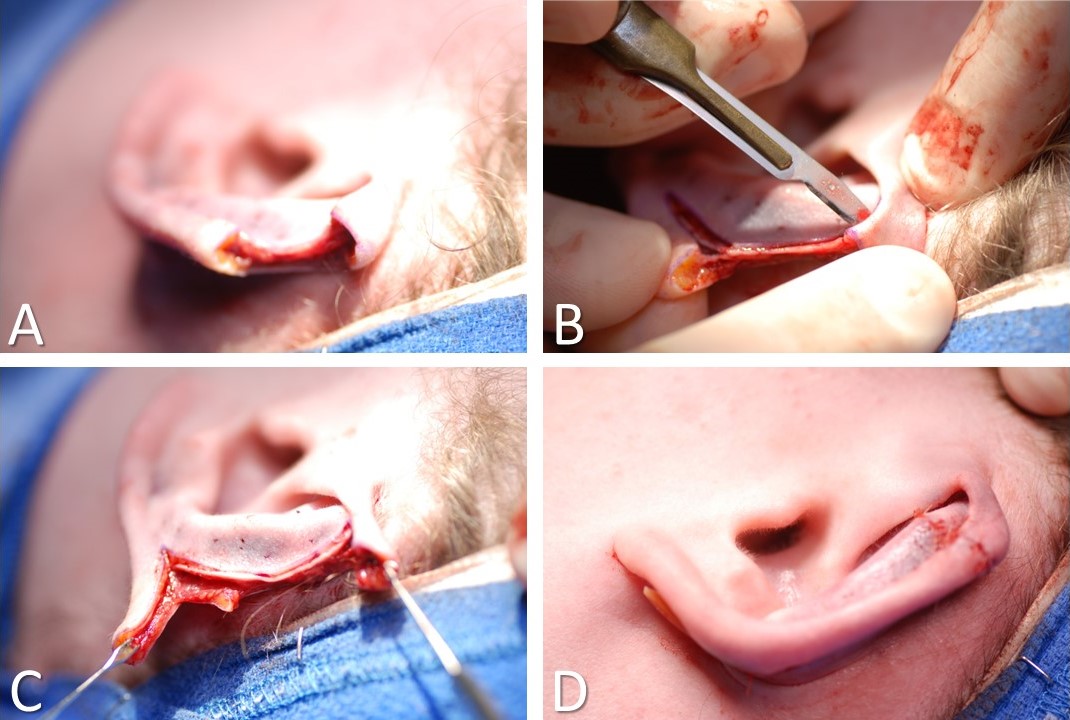

Antia-Buch Flaps

Antia-Buch, or chondrocutaneous helical rim advancement, flaps are used for reconstructing auricular defects that measure up to 2 cm in length but are limited to the helix (see Image. Antia-Buch Flap).[20] In this technique, releasing incisions are made within the junction between the helix and the scaphoid fossa superior and inferior to the defect, cutting through the anterior skin and cartilage only while leaving the posterior skin of the auricle intact because the posterior skin will provide the blood supply to the helical flaps. The posterior skin of the auricle is then undermined sufficiently to permit the necessary amount of advancement before closure. The releasing incisions may be quite lengthy, extending inferiorly as far as the junction of the scaphoid fossa and the lobule and anteriorly/superiorly as far as the junction of the helical root and the face. Please note that the flaps will appear to exceed the standard advancement flap 3:1 length:width ratio when viewed from the anterior surface of the auricle, even though the flaps remain attached to the posterior auricular skin along their entire lengths and maintain robust perfusion. After flap advancement and closure of the defect, there is frequently a standing cutaneous deformity on the posterior aspect of the auricle that must be excised.

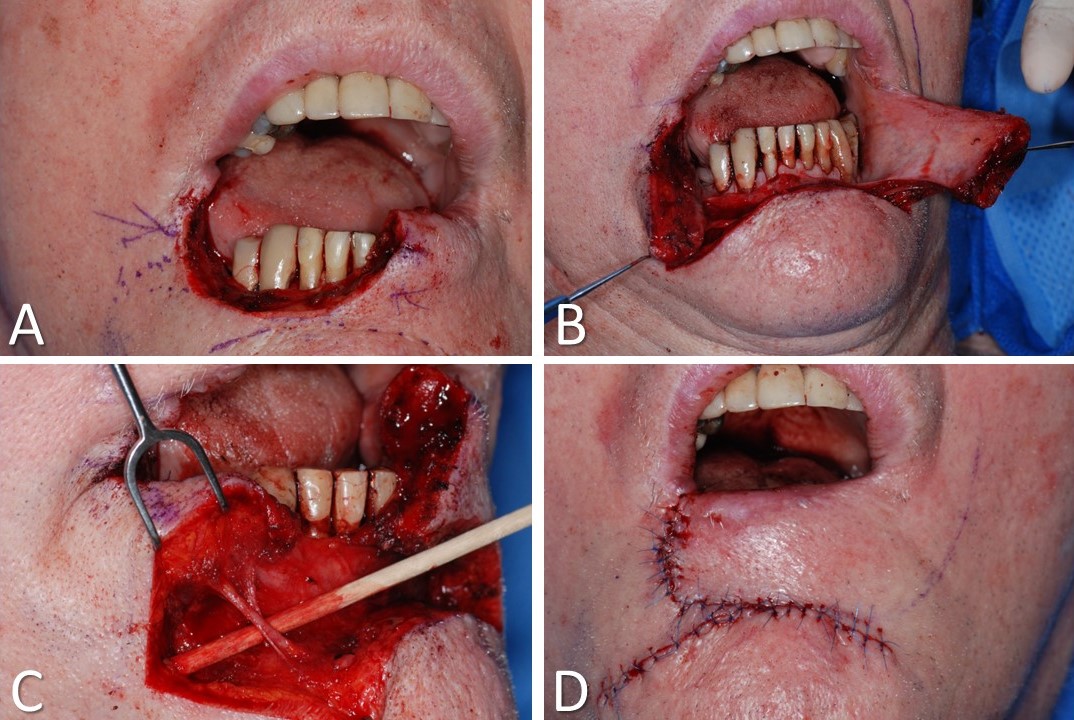

Karapandzic Flaps

Reconstruction of the lips can be accomplished with many techniques, depending upon the width of the defect and its location. Smaller defects, up to one-third of the width of either the upper or lower lip, may be reconstructed with primary closure, often requiring the defect to be extended into a wedge shape, with or without an M-plasty at the apex. Defects up to half the width of the lip may be closed using interpolated flaps, such as Abbé or Estlander flaps, the latter employed when the defect involves the oral commissure and the former when it does not. The Karapandzic composite musculomucocutaneous advancement flap, first described in 1974, is a reliable option for defects up to two-thirds the width of the lip.[21] The advantage of using this flap is that it maintains muscle function and lip sensation by preserving the neurovascular bundles, as does the Rieger dorsal nasal flap, thereby preventing drooling and oral incompetence that may be seen after other reconstructive options are employed. The primary drawback of the Karapandzic technique is that it results in microstomia commensurate to the size of the lip defect that was closed. Releasing incisions for Karapandzic flaps are made in the nasolabial folds and labiomental sulcus for scar camouflage; these are carried down through the skin only (see Image. Karapandzic Flap). The muscle dissection proceeds bluntly to ensure the identification and preservation of branches of the labial and angular arteries and branches of the facial and trigeminal nerves. The mucosa is left intact throughout the procedure. Closure is performed in a layered fashion, and postoperative lips stretching may be necessary after completion, depending on the degree of resulting microstomia.

Complications

The most common complication of local flap reconstructive surgery is either partial or total flap necrosis, leading to wound dehiscence (see Image. Local Flap Complication).[22] Flap loss may result from several causes, but vascular compromise is the most common. Venous congestion is more common than arterial inflow obstruction. Still, both may result from a flap design with insufficient width relative to its length, stretching the flap excessively, which narrows the lumina of small caliber vessels, or excessive flap thinning, which disrupts the subdermal vascular plexus. Vascular compromise may also be caused by extrinsic factors, such as pressure, resulting from compression due to a hematoma or edema due to inflammation or infection. Changes in the color and turgor of the flap will be the first indication of vascular compromise: a dusky, ecchymotic flap that is swollen and firm is likely to suffer from venous insufficiency. In contrast, arterial insufficiency will result in a pale and cool flap. Venous insufficiency, while far more common than arterial insufficiency, will ultimately result in enough congestion to obstruct arterial inflow. If identified early, vascular compromise may be alleviated by releasing some closing sutures, thereby decreasing tension on the flap. If a hematoma has formed under the flap, draining it will promote improved circulation. Infections should be treated with drainage, irrigation, and antibiotics to reduce inflammation. If none of these options are appropriate, applying nitroglycerin paste may improve flap perfusion. Medicinal leeches may also be helpful, as they remove congested blood directly and promote circulation by administering a natural anticoagulant, hirudin. However, antibiotic prophylaxis with a fluoroquinolone should be provided when leeches are employed due to the risk of infection with Aeromonas hydrophila.

After flap necrosis, infection is the most common complication of local flap transfer.[22] In many instances, infection occurs at the site of flap necrosis, either as a cause or a result of the necrosis. Bleeding with potential hematoma formation is the next most common complication. Even in patients taking multiple blood thinners, though, hematomas with appropriate intraoperative hemostasis are rare. Excessive use of electrocautery can, however, contribute to flap necrosis. Lastly, displacement of free margins, such as the eyelid, lip, eyebrow, and nasal ala, are predictable results from flap designs that place tension on these freely mobile structures. To avoid traction on a free margin, the primary tension vector for closure should be parallel to the free margin rather than perpendicular.[23][24] Corticosteroid injections may be employed if scarring causes an untoward cosmetic outcome, particularly within the first few postoperative weeks. If injections do not produce the desired effect, skin resurfacing with dermabrasion or laser treatments may be required. If those options fail, revision surgery may be considered.

Clinical Significance

Local flap advancement represents a versatile approach for reconstructive surgery, especially for wounds that exceed the scope of primary closure. It facilitates the closure of more extensive wounds and ensures an impeccable skin color and texture match with the surrounding region. Attention to meticulous flap design is paramount to mitigate any potential aesthetic consequences of reconstructive surgery by concealing scars within cosmetic subunit boundaries and relaxed skin tension lines. To optimize outcomes, the surgeon should meticulously deliberate factors such as the direction of the primary tension vector, placement of standing cutaneous cone deformities, impact on adjacent anatomical structures, flap vascularity, and the configuration of the defect.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Advancement flaps require a multidisciplinary healthcare team with specific roles and responsibilities to ensure optimal patient-centered care. Physicians, including plastic surgeons and dermatologists, need the skills to assess wound characteristics, choose the most suitable flap type, and perform precise surgical techniques. They must also possess a strong ethical foundation, ensuring informed consent and considering patients' preferences. Nurses are critical in preoperative and postoperative care, monitoring patients for complications, wound healing, and infection prevention. Nurses and surgeons must educate patients in proper aftercare as advancement flaps must be monitored until complete healing occurs.[25][26] Pharmacists contribute by providing medications and ensuring proper pain management, prophylactic antibiotics, and any necessary wound care supplies. Surgeons must collaborate with nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals to ensure a smooth surgical process. They must convey the patient's history, surgical plan, and specific care requirements. Nurses and pharmacists, in turn, should communicate any concerns or changes in the patient's condition to the surgeon promptly. This coordinated approach enhances patient safety, prevents complications, and improves outcomes.

Furthermore, a shared sense of responsibility among the healthcare team members is paramount. Each professional must understand their role in the patient's care and adhere to best practices. Ethical considerations, such as respecting patient autonomy and ensuring informed consent, are non-negotiable. Beyond individual responsibilities, the team should collectively strategize and plan each stage of the surgical procedure and postoperative care, considering patient preferences and safety measures. Team performance is further enhanced through regular training and skill development, staying updated with advancements in flap techniques, and embracing a culture of continuous learning. In summary, for advancement flap procedures, effective teamwork, ethical conduct, skillful execution, and clear communication among healthcare professionals are essential components in delivering patient-centered care that improves outcomes, enhances safety, and optimizes team performance.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Rieger Dorsal Nasal Rotation-Advancement Flap. A) An approximate 2-cm defect of the nasal dorsum resulted from a Mohs resection of a basal cell carcinoma. B) The wound bed was excised down to the supraperichondrial plane to facilitate flap elevation, and the flap incisions were made to permit rotation as well as a V to Y advancement in the glabella. C) The flap is elevated in a supraperichondrial/supraperiosteal plane with care taken to avoid injuring the dorsal nasal and infratrochlear vessels that perfuse the flap. D) The flap is inset; note the slight resulting elevation of the nasal tip.

Contributed by Marc H Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

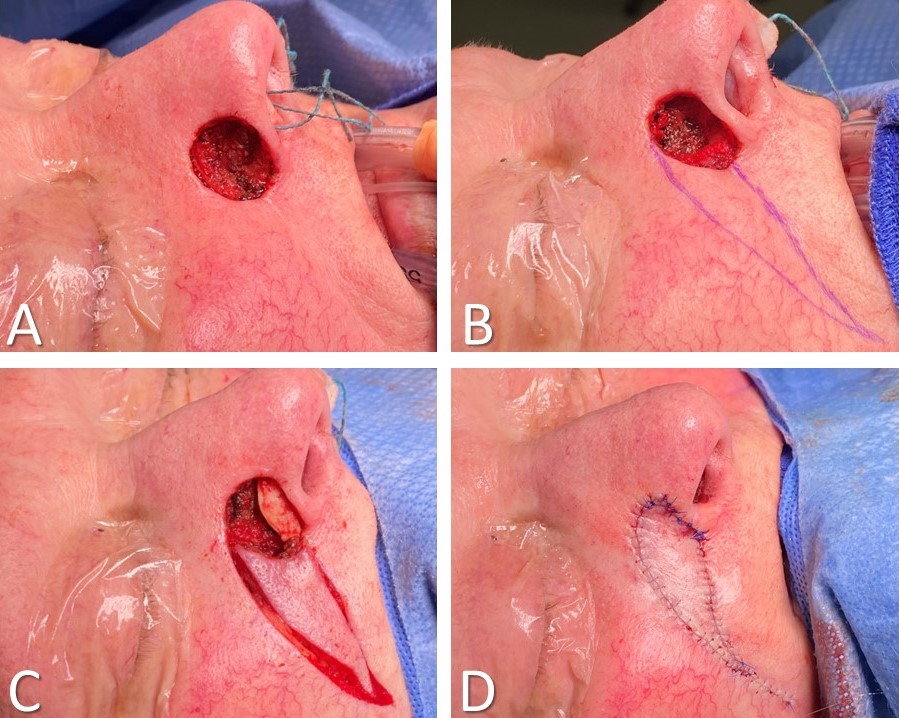

Antia-Buch Helical Advancement Flaps for Auricular Reconstruction. A) 15-mm defect of the helical rim after resection of a basal cell carcinoma. B) Back cuts are made within the scaphoid fossa, longer on the anterior surface than on the posterior. C) The flaps are mobilized. D) The defect is closed.

Contributed by Marc H Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Cervicofacial Advancement-Rotation Flap. A) 3-cm defect from melanoma resection. B) Superficial parotidectomy performed via modified Blair incision. C) Cervicofacial flap elevated in a subdermal plane via extension of the modified Blair incision. D) Flap inset and closed.

Contributed by Marc H Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Karapandzic-Type Advancement of the Lower Lip. A) A defect equal to roughly half the width of the lip. B) Releasing incisions made through the skin only. C) Blunt dissection through the orbicularis oris muscle permits the identification of neurovascular pedicles to preserve motor and sensory function. D) Closure is performed in a vertical relaxed skin tension line and within the labiomental sulcus; note the resulting microstomia, some of which will resolve over time.

Contributed by Marc H Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

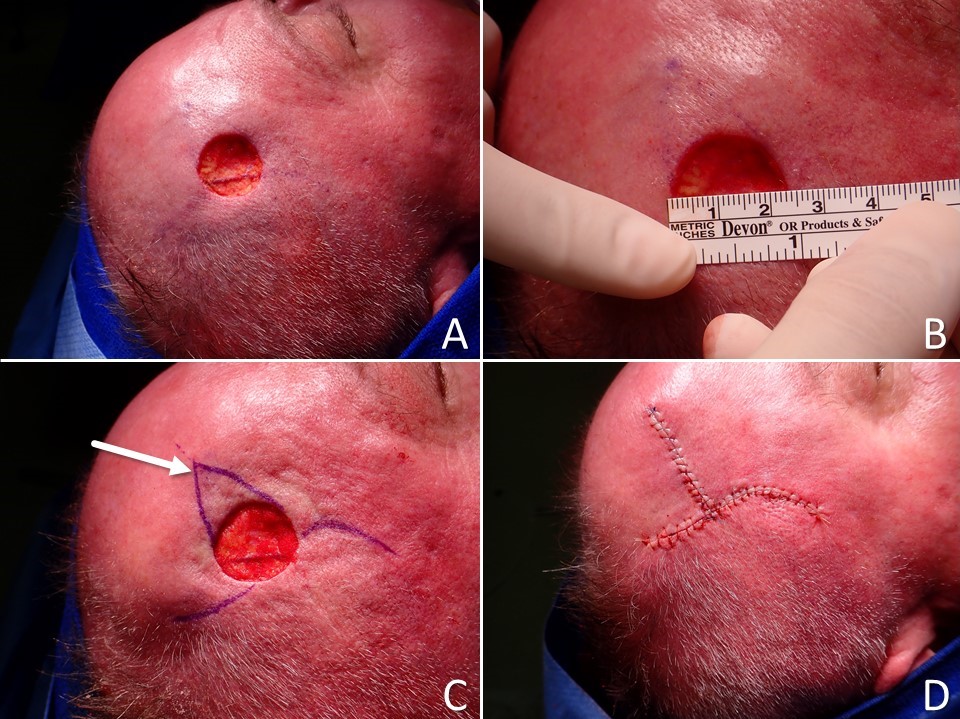

Cheek Advancement Flap. A) 15-mm defect after resection of a squamous cell carcinoma. B) The tissue between the defect and the nasolabial fold is excised in a fusiform shape to hide the scar in the nasofacial junction and nasolabial fold. C) The medial cheek is undermined in a subdermal plane, advanced medially, and closed. D) Appearance at 1-year postoperative follow-up.

Contributed by Marc H Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

V-to-Y Island Advancement Flap. A) A 1 cm defect from resection of basal cell carcinoma. B) Incisions planned in nasolabial fold. C) Conchal cartilage rim graft placed and flap incised; the flap is elevated in a subdermal plane except for its central one-third, which remains fixed to the subdermal fat for perfusion. The surrounding tissue is elevated for secondary movement. D) Flap inset and nasolabial incision is closed.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

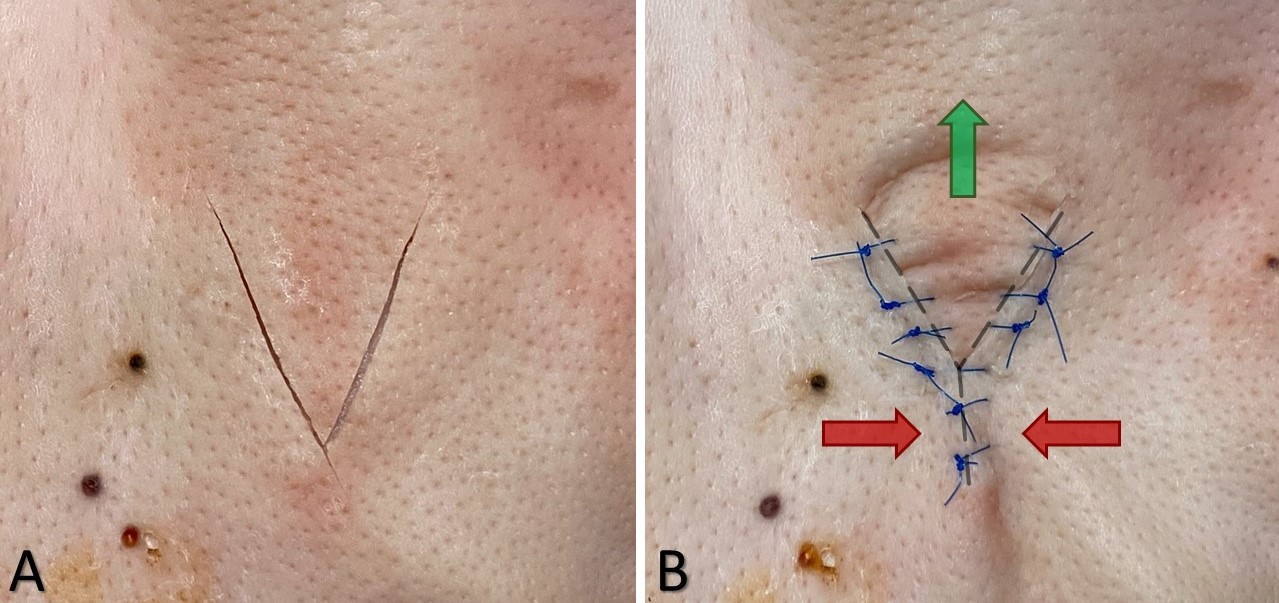

V to Y Advancement. A) V-shaped incision with the apex pointing opposite the advancement direction. B) Y-shaped postoperative appearance. The arrows indicate the direction of tissue advancement, with the red arrows showing the inward movement of the skin that serves to “push” the V-shaped flap in the direction of the green arrow.

Contributed by Joseph S Krivda, MD and Marc H Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

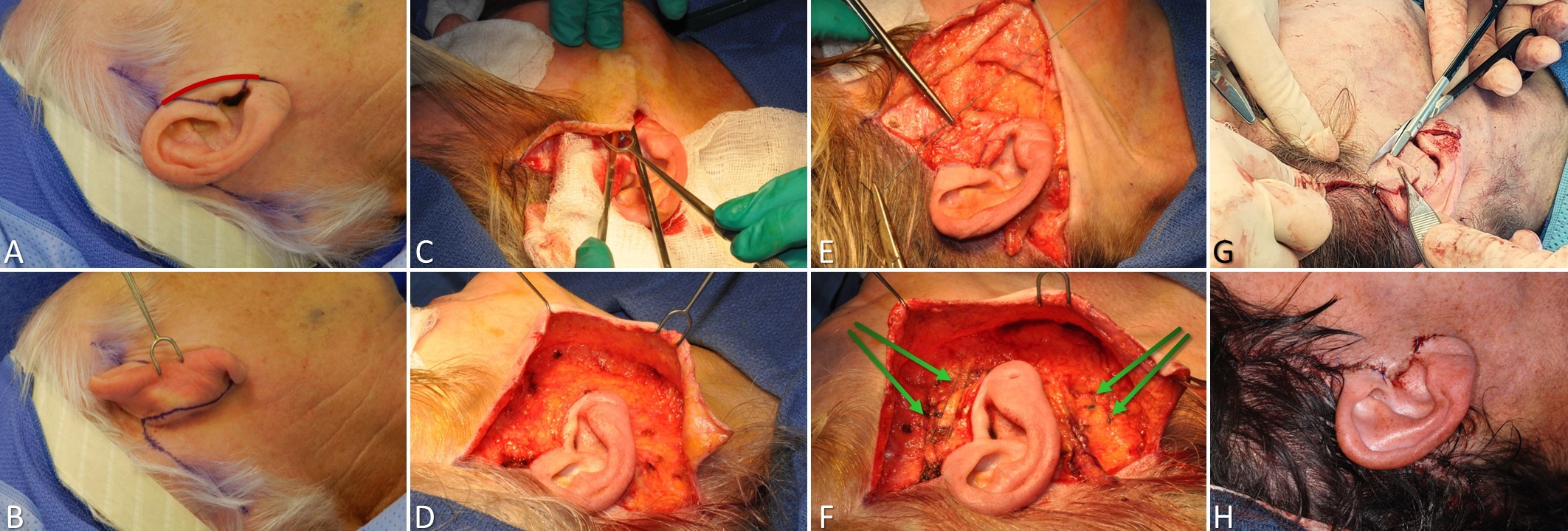

SMAS Plication Rhytidectomy. A) A modified Blair incision is used; the red line represents where the incision is placed for a male. The incision drawn is used for females. B) The incision runs up the posterior auricle, approximately 1/3 the width of the conchal cartilage lateral to the postauricular sulcus so that the incision falls into the sulcus when retraction on the auricle is released. C) The skin flap is elevated in a subdermal plane, using countertraction to facilitate dissection and avoid violating the skin. D) Skin flap elevation extends 4 to 6 cm anterior to the auricle. E) Plication sutures are placed into the SMAS to suspend it posterosuperiorly, in the same vector as oral commissure movement during smiling. F) At least 2 2-0 plication sutures are placed anterior to the auricle and 2 posterior. G) Excess skin is trimmed, leaving enough to close with minimal tension. H) The incision is closed with sutures anterior to the auricle, and staples may be used posteriorly.

Contributed by Marc H Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

O to T Double Rotation Flap. A) circular full-thickness skin defect resulting from wide local excision of a melanoma. B) The defect measures 22 mm in diameter. C) Double rotation flaps are planned for closure with the inferior (right side of image) flap having an advancement component that permits the back cut to lie along the temporal hairline, and the superior flap (left side of image) having a more conventional design (the arrow indicates the triangular standing cutaneous deformity that will be removed). D) The defect is closed with the limbs of the incision well hidden along the hairline and within a transverse forehead rhytid.

Contributed by Marc H Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Bednarek RS, Sequeira Campos M, Hohman MH, Ramsey ML. Transposition Flaps. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763204]

Prohaska J, Sequeira Campos M, Cook C. Rotation Flaps. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29493993]

Ramsey ML, Ellison CA, Hohman MH, Al Aboud AM. Interpolated Flaps. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262248]

Zeitels SM, Hillman RE. A Method for Reconstruction of Anterior Commissure Glottal Webs With Endoscopic Fibro-Mucosal Flaps. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2019 Mar:128(3_suppl):82S-93S. doi: 10.1177/0003489418820031. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30843433]

Abramo AC, Lucena TW, Sgarbi RG, Scartozzoni M. Mastopexy Autoaugmentation by Using Vertical and Triangular Flaps of Mammary Parenchyma Through a Vertical Ice Cream Cone-Shaped Approach. Aesthetic plastic surgery. 2019 Jun:43(3):584-590. doi: 10.1007/s00266-019-01337-1. Epub 2019 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 30843097]

Billington A, Dayicioglu D, Smith P, Kiluk J. Review of Procedures for Reconstruction of Soft Tissue Chest Wall Defects Following Advanced Breast Malignancies. Cancer control : journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center. 2019 Jan-Dec:26(1):1073274819827284. doi: 10.1177/1073274819827284. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30808195]

Zito PM, Jawad BA, Hohman MH, Mazzoni T. Z-Plasty. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29939552]

Mole RJ, Hohman MH, Sebes N. Bilobed Flaps. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262178]

Krishnan R, Garman M, Nunez-Gussman J, Orengo I. Advancement flaps: a basic theme with many variations. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2005 Aug:31(8 Pt 2):986-94 [PubMed PMID: 16042922]

Jennings JJ, Shaffer AD, Stapleton AL. Pediatric nasal septal perforation. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2019 Mar:118():15-20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.12.001. Epub 2018 Dec 4 [PubMed PMID: 30578990]

Cass ND, Terella AM. Reconstruction of the Cheek. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2019 Feb:27(1):55-66. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2018.08.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30420073]

Angeles MA, Martínez-Gómez C, Migliorelli F, Voglimacci M, Figurelli J, Motton S, Tanguy Le Gac Y, Ferron G, Martinez A. Novel Surgical Strategies in the Treatment of Gynecological Malignancies. Current treatment options in oncology. 2018 Nov 9:19(12):73. doi: 10.1007/s11864-018-0582-5. Epub 2018 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 30411170]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGoldminz D, Bennett RG. Cigarette smoking and flap and full-thickness graft necrosis. Archives of dermatology. 1991 Jul:127(7):1012-5 [PubMed PMID: 2064398]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHwang K, Son JS, Ryu WK. Smoking and Flap Survival. Plastic surgery (Oakville, Ont.). 2018 Nov:26(4):280-285. doi: 10.1177/2292550317749509. Epub 2018 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 30450347]

Tomás-Velázquez A, Redondo P. Assessment of Frontalis Myocutaneous Transposition Flap for Forehead Reconstruction After Mohs Surgery. JAMA dermatology. 2018 Jun 1:154(6):708-711. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1213. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29799979]

Larrabee WF Jr, Sutton D. A finite element model of skin deformation. II. An experimental model of skin deformation. The Laryngoscope. 1986 Apr:96(4):406-12 [PubMed PMID: 3959701]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZito PM, Hohman MH, Mazzoni T. Paramedian Forehead Flaps. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763107]

Eren E, Beden V. Beyond Rieger's original indication; the dorsal nasal flap revisited. Journal of cranio-maxillo-facial surgery : official publication of the European Association for Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery. 2014 Jul:42(5):412-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2013.05.031. Epub 2013 Jul 5 [PubMed PMID: 23830767]

Dibelius G, Hohman MH. Rhinoplasty Tip-Shaping Surgery. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33620827]

Stella C, Adam M F, Edward L. Helical Rim Reconstruction: Antia-Buch Flap. Eplasty. 2015:15():ic55 [PubMed PMID: 26491509]

Karapandzic M. Reconstruction of lip defects by local arterial flaps. British journal of plastic surgery. 1974 Jan:27(1):93-7 [PubMed PMID: 4593704]

Zhao Z, Tao Y, Xiang X, Liang Z, Zhao Y. Identification and Validation of a Novel Model: Predicting Short-Term Complications After Local Flap Surgery for Skin Tumor Removal. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2022 Nov 17:28():e938002. doi: 10.12659/MSM.938002. Epub 2022 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 36384866]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKarjalainen T, Sebastin SJ, Chee KG, Peng YP, Chong AKS. Flap Related Complications Requiring Secondary Surgery in a Series of 851 Local Flaps Used for Fingertip Reconstruction. The journal of hand surgery Asian-Pacific volume. 2019 Mar:24(1):24-29. doi: 10.1142/S242483551950005X. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30760139]

Hand LC, Maas TM, Baka N, Mercier RJ, Greaney PJ, Rosenblum NG, Kim CH. Utilizing V-Y fasciocutaneous advancement flaps for vulvar reconstruction. Gynecologic oncology reports. 2018 Nov:26():24-28. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2018.08.007. Epub 2018 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 30186930]

Kim GW, Bae YC, Kim JH, Nam SB, Kim HS. Usefulness of the orbicularis oculi myocutaneous flap in periorbital reconstruction. Archives of craniofacial surgery. 2018 Dec:19(4):254-259. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2018.02019. Epub 2018 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 30613086]

Habiba NU, Khan AH, Khurram MF, Khan MK. Treatment options for partial auricle reconstruction: a prospective study of outcomes and patient satisfaction. Journal of wound care. 2018 Sep 2:27(9):564-572. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2018.27.9.564. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30204580]