Introduction

Acrodynia is a manifestation of chronic mercury poisoning or idiosyncrasy with mercury. This symptom complex includes dermatological and systemic manifestations of exposure to various forms of mercury.[1] It is a Greek term that means 'painful extremities.' In literature, it is addressed by other names like erythema arthricum epidemica, erythredema polyneuropathy, hydrargyria, and Feer syndrome, but 'pink's disease' is the most common alternate name.[2] Acrodynia is a rare disease, but sporadic cases are often reported.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Acrodynia is related more often to the elemental form of mercury (quicksilver) inorganic salts than the organic forms.[3] The elemental form is either liquid or vapor and is widely used in thermometers, blood cuffs, batteries, dental amalgams, fluorescent light bulbs, etc. The inhalational toxicity of quicksilver is more severe than that of oral toxicity. The organic forms of mercury can exist as short-chain, alkyl-mercury compounds (methylmercury and ethylmercury) or long-chain, aryl-mercury compounds (methoxyethyl mercury and phenylmercury). In particular, the toxicity of organic forms is related to consuming contaminated seafood.

Epidemiology

There is no exact data regarding the present prevalence of acrodynia. The disease is mostly seen in infants and young children. Newborn babies and adults are less vulnerable. The condition was prevalent in Europe, America, and Australia in the first half of the twentieth century.[4] It was present in every 500 children exposed to mercury in dental amalgams.[5] The incidences were more common in infants and children under 2 years and highest among the age group of months.[6] The earlier research resulted in the withdrawal of mercury-containing tooth powders from the market and decreased morbidity and mortality. Between 1939 and 1948, the official death record from acrodynia was 585 in England, which dropped to 57 in 1957 and 7 in 1955.[7]

Only rare cases of acrodynia with varied presentations are reported in the literature, most of which are related to accidental exposure to mercury in non-occupational settings. Mercury-containing preservatives (thiomersal), calomel-containing diaper powders, plant fungicides, anthelmintics, mercury ointments, certain bactericidal agents, alternate medicine drugs, folk medicines, and interior latex paints pose a hazard of causing mercury toxicity in domestic settings.[8] Certain traditional ayurvedic medicines contain a significant amount of mercury and have caused cases of acrodynia.[9]

Pathophysiology

Mercury has an affinity for the ubiquitous sulfhydryl groups in the tissues in its various forms by forming covalent bonds. The interaction of mercury with many intracellular moieties results in the dysfunction of enzymes, membrane transportation, and structural proteins. Mercury can produce corrosive actions locally due to its oxidizing and corrosive action. Mercury absorption can manifest in varied forms due to its vast systemic involvement. The immune system's involvement in delayed hypersensitivity has been proposed to cause acrodynia. There can be genetic variation in individuals' idiosyncratic sensitivity due to mercury's toxic effects.[10]

The mechanism of acrodynia may also involve adrenocortical hyperfunction, sympathetic vasomotor dysfunction, and catecholamine dysfunction. The inactivation of catecholamine-0-methyl transferase can explain arterial hypertension associated with mercury, increasing serum and urinary epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine.[11] The neural degeneration associated with mercury poisoning is responsible for the painful extremities, peripheral neuropathy, and associated neuropsychiatric symptoms, as seen in acrodynia.[12]

Toxicokinetics

Absorption

The toxic effects of mercury depend on the form of mercury, age of the individual, route of exposure, biotransformation, accumulation in the target organs, and comorbidities. The vaporized form of elemental mercury is more readily absorbed than the oral or intravenous route. The elemental mercury can be volatile at room temperature, and the volatility increases with temperatures and aerosolization.[13] The absorption of elemental is insignificant on oral ingestion. Still, conditions like abnormal gastrointestinal (GI) motility, fistulae, and perforation can lead to the entry of elemental mercury into the peritoneal space, where it can be oxidized to inorganic forms. The inorganic salts and organic forms of mercury are mainly absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract after oral absorption. The absorption of the organic forms of mercury is more rapid than the organic salts due to their lipophilic properties.

Distribution and Biotransformation

After absorption, mercury gets widely distributed in the various body tissues, mainly the kidneys, liver, kidney, and central nervous system. The vaporized form of elemental mercury has a high affinity for accumulation in the nervous system due to its lipid affinity. The toxicity of elemental mercury eventually depends on its conversion to ionic mercury by catalase enzyme. The inorganic forms of mercury have an affinity for renal tissue, in particular the renal tubules.[14] The mercury ions' penetration of the blood-brain barrier is poor due to low lipid solubility. The organic forms of mercury can accumulate in the various tissues and cross the blood-brain barrier and placenta. The ease of transformation across the placental barrier has been associated with neurological degeneration in the fetus, as documented in the prenatally exposed infants showing manifestations of Minamata disease. The methyl forms significantly accumulate in the RBCs and the hair.

Elimination

The elemental and inorganic forms of mercury are primarily excreted by glomerular filtration and tubular secretion. Lungs, skin, and feces eliminate a small amount of elemental and inorganic forms of mercury. Both forms' biological half-life is estimated at nearly 30 to 60 days.[15] On the other hand, the organic forms of mercury undergo significant enterohepatic circulation with a biological half-life of about 70 days.[16]

History and Physical

The initial history can be vague and mimic other conditions. The common presenting signs in an affected child are irritability, peevishness, poor appetite, unexplained drowsiness, weight loss, apathy, painful extremities, and increased sweating. The parents may complain of decreased playfulness owing to muscle atrophy and pain. The initial signs are followed by redness of toes, fingers, and tip of the nose. Photophobia, conjunctivitis, and keratitis are often coexistent.[17]

Other important signs include pruritis, pyrexia of unknown origin, drooling of saliva, degeneration of nails and teeth, swollen gums, tremors, alopecia, miliaria, generalized weakness, sleep disturbances, and secondary skin infections.[18]

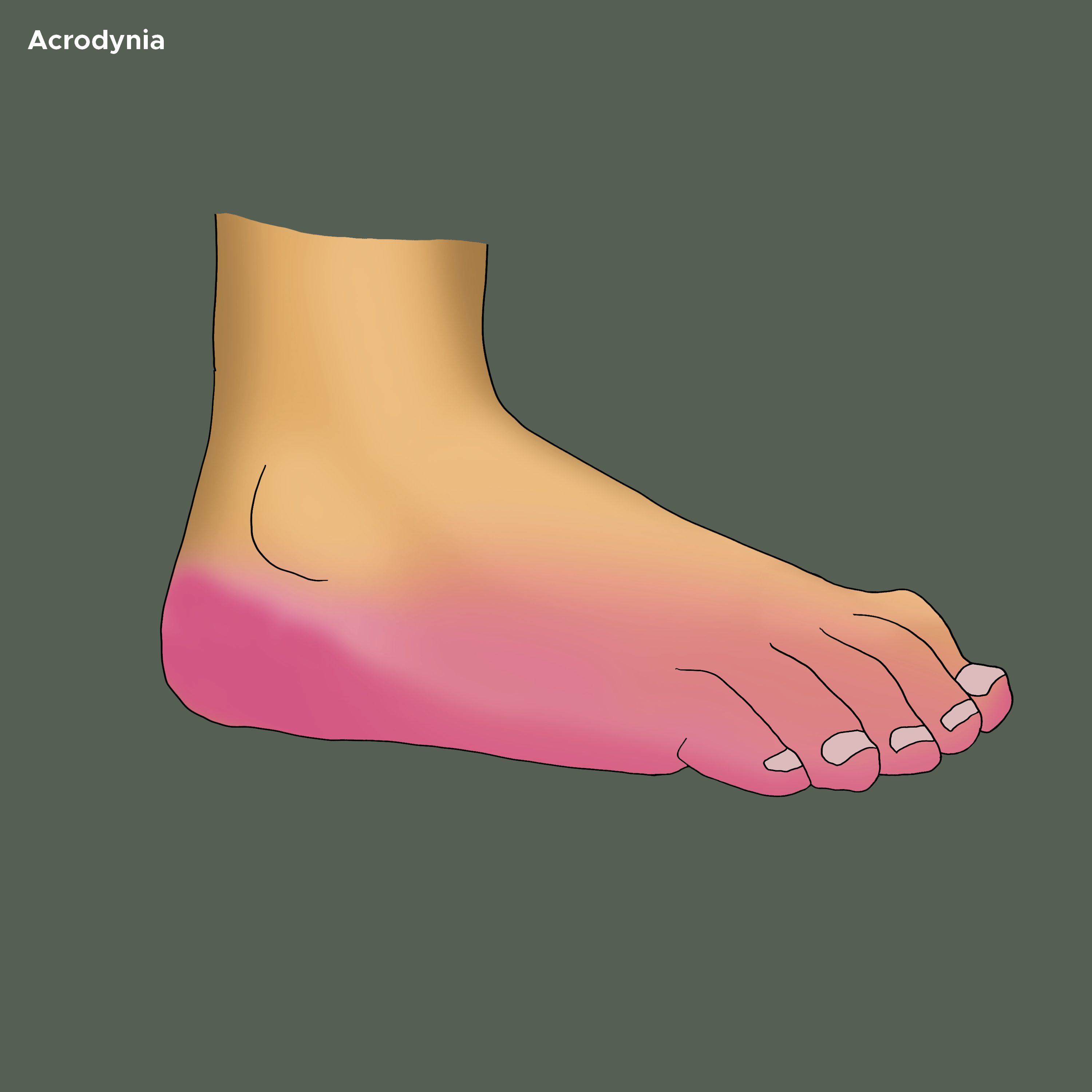

The skin of palms and soles may show vesicular eruption and subsequent desquamation. The palms and feet may be swollen and show dusky discoloration (see Image. Acrodynia on the Bottom of Foot). A morbilliform, scarlatiniform, or rubelliform exanthem can be seen with hemorrhagic puncta. The repetitive scratching of hands may cause lichenification, excoriation, and ulcerating pyoderma. One author describes The cutaneous features as ‘puffy, pink, painful, paresthetic, perspiring, and peeling hands.’[19]

A cutaneous biopsy may show non-specific findings of chronic dermatitis and hyperplastic sweat glands.[20] The blood pressure is raised, and the child often has tachycardia. The atrophy of muscles of the pelvic and pectoral girdle should be assessed. Occasionally, the patient can show a ‘Salaam posture,’ in which he sits with the head between the legs and rubs the hands together.[21] The nerve biopsy can show myelin destruction and perinuclear chromatolysis in anterior horn cells.[22] The involvement of other systems may be evidenced by bronchitis, dyspepsia, and upper respiratory infections.

Evaluation

Before commencing the workout, a thorough clinical history and an evaluation of the possible exposures in the domestic surroundings and the workplace are crucial. The laboratory evaluation should include the demonstration of mercury levels in the blood, urine, and body tissues. The initial exercise should consist of radiological evaluation, toxicological screening of blood and urine, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, and complete blood profile. Spot urine collections can be used for creatinine estimations, but a 24-hour urine sample should estimate the urine mercury concentrations.[23]

Gas and thin-layer chromatography are useful in distinguishing mercury's organic and inorganic salts. A toxicology screening should be done to rule out other heavy metal poisonings. Estimations of the urinary levels of vanillylmandelic acid, homovanillic acid, and 17-ketosteroid should be done in patients with concurrent hypertension and endocrinological involvement.[24] Electroneuromyography, cardiovascular evaluation, and neuropsychological tests should be employed if necessary.

While making inferences, it is essential to note that there is no established correlation between the symptomatology of mercury toxicity and its concentrations in body fluids.[25] Literature has mentioned the mercury assay of hair in chronic poisonings, but it is prone to misinterpretations.[26]

Treatment / Management

Elimination of the source of exposure is the first crucial step in initiating the treatment. The initial therapy should aim to correct the fluid and electrolyte imbalances. All cases of inhalational toxicity of elemental mercury need monitoring of vital organs. Whole-bowel irrigation by polyethylene and gastric decontamination by activated charcoal can be rarely indicated but can be attempted.[27][1]

Meso 2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid (succimer, DMSA) is an FDA-approved water-soluble analog of BAL (British anti-Lewisite) and forms the mainstay of treatment. WHO recommends succimer therapy to be initiated in children with urine mercury levels of 50 μg/mL or more creatinine, even if the child is asymptomatic.[28] DMSA can be given orally or intravenously. The dose for children is 350 mg/m2 3 times daily for the first 5 days, then 350 mg/m2 twice daily for the next 14 days. Depending on the remission of symptoms, the dose can be repeated after 2 weeks. The child's CBC, renal, and hepatic function should be monitored during treatment.[29] BAL (dimercaprol ) and D-penicillamine have also been used to treat acrodynia. BAL should be avoided when treating mercury toxicity since it may aggravate mercury accumulation in the nervous system. In case of unavailability of succimer, D-penicillamine can be used in the daily dosage of 20 to 30 mg/kg in 4 divided doses. D-penicillamine is not useful for organic mercury toxicity and can cause more severe side effects like nephrotoxicity.[30] (B3)

Antihypertensive drugs like tolazoline, amlodipine, and labetalol can be used to treat coexistent hypertension. Hemodialysis should be reserved for the refractory cases of renal failure secondary to mercury toxicity. The role of peritoneal dialysis and plasma exchange has also been described.[31] Peripheral pain should be treated with gabapentin and pregabalin. Local application of ointments containing lidocaine and ketamine can be prescribed. Skin conditions like secondary infections and pyoderma can warrant antibiotic use due to cultural sensitivity. The diet must be encouraged in patients with anorexia. An environmental survey is essential for patient management in mercury poisoning. It should aim towards decontaminating the domestic and industrial surroundings in a scientifically prescribed manner.(B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosis of acrodynia can be difficult for clinicians due to the nonspecific systematic manifestations of mercury toxicity and the rarity of the disease in the present times. The dermatological findings can be confused with other skin conditions like postviral acral desquamation, Kawasaki disease, juvenile plantar dermatosis, erythromelalgia, etc.[2][32] Contact exposure to mercury can result in other cutaneous conditions like acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and Symmetric flexural exanthema.[18][19]

The involvement of other systems like the nervous, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and respiratory systems can complicate the diagnosis of acrodynia. The common systemic diseases confused with the diagnosis of acrodynia are pheochromocytoma, idiopathic hypertension in the pediatric age group, and Kawasaki disease.[33][34][35][36] Simultaneously, toxicities of other heavy metals like gold, arsenic, copper, and thallium can mimic the clinical presentation of acrodynia. In the pediatric population, acrodynia can be misdiagnosed as brucellosis, hyperthyroidism, Guillain Barré syndrome, sepsis, etc.[37] The clinical presentation of pink’s disease has been confused with viral infections and nutritional deficiencies.[38]

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on age, idiosyncrasy, dose, and duration of exposure. The prognosis can be variable but is often favorable. In most cases, the symptoms are alleviated with chelation therapy. Elderly children seem to have a better recovery. In earlier times, the fatality of deaths was as high as 10 to 33%. Infertility (Young disease), bronchiectasis, mental retardation, and permanent neurological deficits have been reported in the survivors. A high prevalence of autism spectrum disorders among descendants of survivors of pink’s disease is also documented.[5]

Pearls and Other Issues

Unfortunately, despite treatment, some patients are disabled and have a poor quality of life. The organic damage suffered from mercury is often irreversible, and patients often have marked changes in intelligence and cognition. Patients with a short exposure to mercury can recover fully if mercury exposure is discontinued.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of acrodynia involve a high suspicion based on exposure and a multidisciplinary approach. Although various jurisdictions have imposed policies to curb mercury exposure, practitioners can encounter cases of acrodynia. There is a growing trend of intake of herbal and ayurvedic medicines, which may contain an abnormally high amount of mercury and its variants. Diagnosing acrodynia can be challenging, given various conditions mimicking the clinical presentation. The health care professional should emphasize an environmental survey, regular follow-up, and proper choice of chelating agents for better treatment outputs.

Media

References

Posin SL, Kong EL, Sharma S. Mercury Toxicity. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763110]

Mercer JJ, Bercovitch L, Muglia JJ. Acrodynia and hypertension in a young girl secondary to elemental mercury toxicity acquired in the home. Pediatric dermatology. 2012 Mar-Apr:29(2):199-201. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01737.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22409470]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMichaeli-Yossef Y, Berkovitch M, Goldman M. Mercury intoxication in a 2-year-old girl: a diagnostic challenge for the physician. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany). 2007 Jun:22(6):903-6 [PubMed PMID: 17310361]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWARKANY J, HUBBARD DM. Acrodynia and mercury. The Journal of pediatrics. 1953 Mar:42(3):365-86 [PubMed PMID: 13035637]

Shandley K, Austin DW. Ancestry of pink disease (infantile acrodynia) identified as a risk factor for autism spectrum disorders. Journal of toxicology and environmental health. Part A. 2011:74(18):1185-94. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2011.590097. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21797771]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHanson M, Pleva J. The dental amalgam issue. A review. Experientia. 1991 Jan 15:47(1):9-22 [PubMed PMID: 1999251]

DATHAN JG, HARVEY CC. PINK DISEASE-TEN YEARS AFTER (THE EPILOGUE). British medical journal. 1965 May 1:1(5443):1181-2 [PubMed PMID: 14273529]

Bose-O'Reilly S, McCarty KM, Steckling N, Lettmeier B. Mercury exposure and children's health. Current problems in pediatric and adolescent health care. 2010 Sep:40(8):186-215. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2010.07.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20816346]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWeinstein M, Bernstein S. Pink ladies: mercury poisoning in twin girls. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2003 Jan 21:168(2):201 [PubMed PMID: 12538551]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAustin DW, Spolding B, Gondalia S, Shandley K, Palombo EA, Knowles S, Walder K. Genetic variation associated with hypersensitivity to mercury. Toxicology international. 2014 Sep-Dec:21(3):236-41. doi: 10.4103/0971-6580.155327. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25948960]

Houston MC. Role of mercury toxicity in hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and stroke. Journal of clinical hypertension (Greenwich, Conn.). 2011 Aug:13(8):621-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00489.x. Epub 2011 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 21806773]

Ding Y, Song R, Li CJ. [The neurological manifestations of chronic mercury poisoning]. Zhonghua nei ke za zhi. 2011 Nov:50(11):950-3 [PubMed PMID: 22333129]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSchwartz JG, Snider TE, Montiel MM. Toxicity of a family from vacuumed mercury. The American journal of emergency medicine. 1992 May:10(3):258-61 [PubMed PMID: 1316757]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePark JD, Zheng W. Human exposure and health effects of inorganic and elemental mercury. Journal of preventive medicine and public health = Yebang Uihakhoe chi. 2012 Nov:45(6):344-52. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2012.45.6.344. Epub 2012 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 23230464]

Clarkson TW. The toxicology of mercury. Critical reviews in clinical laboratory sciences. 1997:34(4):369-403 [PubMed PMID: 9288445]

Hong YS, Kim YM, Lee KE. Methylmercury exposure and health effects. Journal of preventive medicine and public health = Yebang Uihakhoe chi. 2012 Nov:45(6):353-63. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2012.45.6.353. Epub 2012 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 23230465]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEkinci M, Ceylan E, Keleş S, Cağatay HH, Apil A, Tanyıldız B, Uludag G. Toxic effects of chronic mercury exposure on the retinal nerve fiber layer and macular and choroidal thickness in industrial mercury battery workers. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2014 Jul 24:20():1284-90. doi: 10.12659/MSM.890756. Epub 2014 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 25056093]

Lai O, Parsi KK, Wu D, Konia TH, Younts A, Sinha N, McNelis A, Sharon VR. Mercury toxicity presenting as acrodynia and a papulovesicular eruption in a 5-year-old girl. Dermatology online journal. 2016 Mar 16:22(3):. pii: 13030/qt6444r7nc. Epub 2016 Mar 16 [PubMed PMID: 27136627]

Boyd AS, Seger D, Vannucci S, Langley M, Abraham JL, King LE Jr. Mercury exposure and cutaneous disease. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2000 Jul:43(1 Pt 1):81-90 [PubMed PMID: 10863229]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWyllie WG, Stern RO. Pink Disease: its Morbid Anatomy, with a Note on Treatment. Archives of disease in childhood. 1931 Jun:6(33):137-56 [PubMed PMID: 21031845]

Javett SN, Kaplan B. Acrodynia treated with D-penicillamine. American journal of diseases of children (1960). 1968 Jan:115(1):71-3 [PubMed PMID: 5635062]

Roos PM, Dencker L. Mercury in the spinal cord after inhalation of mercury. Basic & clinical pharmacology & toxicology. 2012 Aug:111(2):126-32. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2012.00872.x. Epub 2012 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 22364490]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNayfeh A, Kassim T, Addasi N, Alghoula F, Holewinski C, Depew Z. A Challenging Case of Acute Mercury Toxicity. Case reports in medicine. 2018:2018():1010678. doi: 10.1155/2018/1010678. Epub 2018 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 29559996]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCarter M, Abdi A, Naz F, Thabet F, Vyas A. A Mercury Toxicity Case Complicated by Hyponatremia and Abnormal Endocrinological Test Results. Pediatrics. 2017 Aug:140(2):. pii: e20161402. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1402. Epub 2017 Jul 13 [PubMed PMID: 28701428]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKazantzis G. Mercury exposure and early effects: an overview. La Medicina del lavoro. 2002 May-Jun:93(3):139-47 [PubMed PMID: 12197264]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNuttall KL. Interpreting hair mercury levels in individual patients. Annals of clinical and laboratory science. 2006 Summer:36(3):248-61 [PubMed PMID: 16951265]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceŢincu RC, Cobilinschi C, Ghiorghiu Z, Macovei RA. Acute mercury poisoning from occult ritual use. Romanian journal of anaesthesia and intensive care. 2016 Apr:23(1):73-76. doi: 10.21454/rjaic.7518.231.mep. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28913479]

Forman J, Moline J, Cernichiari E, Sayegh S, Torres JC, Landrigan MM, Hudson J, Adel HN, Landrigan PJ. A cluster of pediatric metallic mercury exposure cases treated with meso-2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA). Environmental health perspectives. 2000 Jun:108(6):575-7 [PubMed PMID: 10856034]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRafati-Rahimzadeh M, Rafati-Rahimzadeh M, Kazemi S, Moghadamnia AA. Current approaches of the management of mercury poisoning: need of the hour. Daru : journal of Faculty of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences. 2014 Jun 2:22(1):46. doi: 10.1186/2008-2231-22-46. Epub 2014 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 24888360]

Güngör O, Özkaya AK, Kirik S, Dalkiran T, Güngör G, Işikay S, Davutoğlu M, Dilber C. Acute Mercury Poisoning in a Group of School Children. Pediatric emergency care. 2019 Oct:35(10):696-699. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27977534]

Yoshida M, Satoh H, Igarashi M, Akashi K, Yamamura Y, Yoshida K. Acute mercury poisoning by intentional ingestion of mercuric chloride. The Tohoku journal of experimental medicine. 1997 Aug:182(4):347-52 [PubMed PMID: 9352627]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMutter J, Yeter D. Kawasaki's disease, acrodynia, and mercury. Current medicinal chemistry. 2008:15(28):3000-10 [PubMed PMID: 19075648]

Brannan EH, Su S, Alverson BK. Elemental mercury poisoning presenting as hypertension in a young child. Pediatric emergency care. 2012 Aug:28(8):812-4. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182628a05. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22863825]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKhodashenas E, Aelami M, Balali-Mood M. Mercury poisoning in two 13-year-old twin sisters. Journal of research in medical sciences : the official journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. 2015 Mar:20(3):308-11 [PubMed PMID: 26109979]

Yeter D, Portman MA, Aschner M, Farina M, Chan WC, Hsieh KS, Kuo HC. Ethnic Kawasaki Disease Risk Associated with Blood Mercury and Cadmium in U.S. Children. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2016 Jan 5:13(1):. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13010101. Epub 2016 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 26742052]

Yeter D, Deth R, Kuo HC. Mercury promotes catecholamines which potentiate mercurial autoimmunity and vasodilation: implications for inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate 3-kinase C susceptibility in kawasaki syndrome. Korean circulation journal. 2013 Sep:43(9):581-91. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2013.43.9.581. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24174958]

Sasan MS, Hadavi N, Afshari R, Mousavi SR, Alizadeh A, Balali-Mood M. Metal mercury poisoning in two boys initially treated for brucellosis in Mashhad, Iran. Human & experimental toxicology. 2012 Feb:31(2):193-6. doi: 10.1177/0960327111417265. Epub 2011 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 21803782]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDally A. The rise and fall of pink disease. Social history of medicine : the journal of the Society for the Social History of Medicine. 1997 Aug:10(2):291-304 [PubMed PMID: 11619497]