Introduction

Abdominal wall reconstruction has become a frequently used term to describe hernia repairs that try to recreate the abdominal wall and restore function and structure. Although there has been no universally agreed-upon definition of a functional abdominal wall, many surgeons believe this involves the closure of the fascia at the midline, often with reinforcement using mesh prosthetics.[1]

The integrity of the abdominal wall is vital as it serves to protect the internal organs, supports the spine and helps maintain an upright posture. Also, the abdominal wall aids in the performance of several bodily functions requiring the generation of Valsalva such as urination, coughing, and defecation. There are also data suggesting an absence of an intact abdominal wall can lead to a sensation of insatiety, possibly contributing to weight gain.

Hernia Risks

Incisional hernia following exploratory laparotomy occurs in 5 - 20% of patients. Risk factors for incisional hernia formation include (1) immunosuppression, (2) wound infection, (3) extreme obesity, (4) malnutrition, (5) patient age, (6) prior abdominal surgery, (7) and any medical condition that is associated with an increase in intra-abdominal pressure in the postoperative period. Other biological factors that may increase risk include have a connective tissue disorder like Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, history of the aneurysmal disease, a diet high in chickpeas, or lathyrism.[2]

Several tumors can occur on the abdominal wall, though these are rare. The most common are desmoid tumors, which often are very locally invasive though histologically benign. Treatment of desmoids often requires full-thickness abdominal wall excision. Despite this, local recurrence rates are 40 to 50%. Most recurrences occur within the first 24 months after surgery. In some cases, adjuvant radiation therapy is recommended especially when the surgical margins are not cleared.[3]

Management of malignant lesions of the abdominal wall requires aggressive resection of the subcutaneous tissues and skin, as well as any involved muscle. Sarcomas are the most common malignant tumors of the abdominal wall and require aggressive resection followed by radiotherapy. Metastatic abdominal wall tumors also exist and may require surgical resection; proposed mechanisms are either via hematogenous or contiguous spread. Reconstruction of the abdominal wall in these cases is usually dictated by the extent of resection and the possible need for further oncologic surgical intervention.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

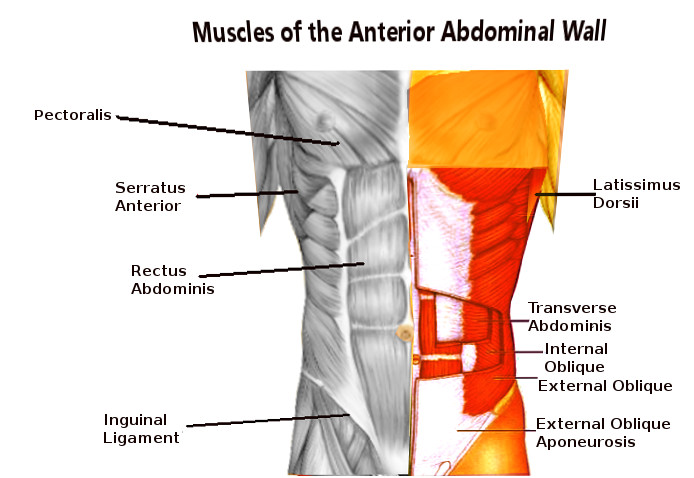

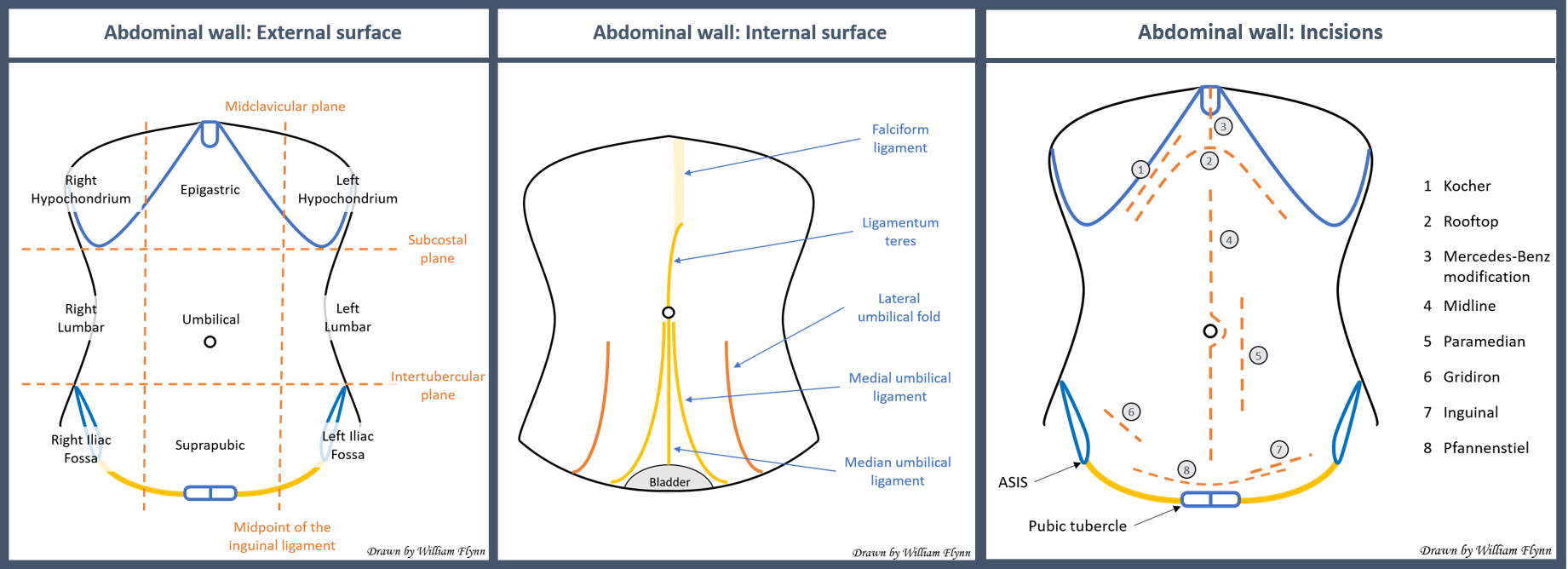

The abdominal wall comprises distinct layers encompassing skin, subcutaneous tissue, fascia, muscle, and peritoneum. Knowledge of the pertinent anatomy, including neurovascular anatomy, of the abdominal wall is paramount to achieve successful abdominal wall reconstruction.

Indications

Indications for reconstruction of the abdominal wall include structural defects or symptoms, with goals ranging from providing pain relief to prevention of strangulation or incarceration. However, it is important to remember that while the size of the abdominal wall defect can be associated with herniation of abdominal contents, the size of the defect is inversely proportional to the risk of incarceration (e.g. - small defects may not be symptomatic but are at higher risk of incarceration, whereas large defects are often noticeable and bothersome, but present much lower incarceration risk). Abdominal wall defects that eventually require reconstruction include those arising from the removal of cancer, management of severe infections, and repair of prior abdominal wounds.[4]

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications to abdominal wall reconstruction include the inability to tolerate general anesthesia. As abdominal wall reconstruction represents a major abdominal surgery, several considerations and relative contraindications exist. One of the most common risks associated with abdominal wall reconstruction is surgical site infection. Surgical site infection, while uncommon, greatly increases the risk of recurrent hernia. Current smoking is a relative contraindication for abdominal wall construction for many surgeons secondary to the increased risk of surgical site infection and wound breakdown. Many surgeons require at least 30 days of smoking cessation before surgery will be attempted. Extreme obesity and uncontrolled diabetes also are relative contraindications, and surgeons should work with patients to achieve weight loss and control of diabetes before major abdominal wall reconstruction.[5]

Equipment

Standard equipment for major abdominal surgery is required. Mesh prosthetics are also typically required for abdominal wall reconstruction and can be left to the discretion of the surgeon. Surgeons should, however, know about the available mesh prosthetics and their properties including the advantages and disadvantages of each of the categories.

Personnel

As these cases represent major abdominal surgery, an assistant (either surgical trainee, physician assistant, or scrub technician) is often needed to aid in retraction during surgery.

Preparation

The patient should be prepared as in any other standard abdominal surgery. Preoperative optimization with weight loss and nutrition management, comorbidity management, and smoking cessation should be performed. The patient is placed in the supine position with arms tucked and appropriate padding as per any other major abdominal surgery.

Technique or Treatment

To achieve midline fascial closure, especially in larger hernias, components of the abdominal wall must be separated to allow for tension-free repairs.[6] Various component separation techniques have been described and involve separating and/or releasing muscle and fascial layers of the abdominal wall. The most commonly used component separation, first described by Ramirez, involves cutting the posterior rectus sheath, mobilizing soft tissue off of the external oblique fascia, and then incising the external oblique fascia approximately lateral to the linea semilunaris. This technique gained widespread popularity but has subsequently been modified to perform the soft tissue mobilization and external oblique incision only. One of the most widely-performed ventral hernia repair techniques also uses component separation. Often called the “Rives-Stoppa,” or retro rectus, repair this procedure involves incision of the posterior rectus sheath on both sides, sewing the posterior rectus sheath together, placing a mesh prosthetic in the retro rectus space, and then closing the anterior fascia. A more recent component separation technique involves the incision of the posterior rectus fascia, and an additional component separation technique, described by Novitsky (often called transversus abdominis release), involves performing a Rives-Stoppa repair but then incising the transversus abdominis muscle proximal to the neurovascular bundles, allowing re-entry into the preperitoneal space and placement of a large mesh prosthetic. The proposed benefit of this technique is it allows the placement of large pieces of mesh without making large skin and subcutaneous flaps, thereby minimizing the risk of wound infection.[7],[8]

Complications

The complications of abdominal wall reconstruction are similar to any other major abdominal surgery. Adhesion lysis is often required intraoperatively, and the risk of bowel perforation should be discussed with the patient, including the very rare need for an ostomy if the bowels cannot be safely closed primarily. Since this surgery often requires extensive dissection and undermining of the skin and soft tissue, wound complications remain a real concern. These can range from simple surgical site infections to deep space infections or significant skin/subcutaneous/flap necrosis. Mesh infections are a dreaded complication of abdominal wall reconstruction, but typically can be minimized with good preoperative optimization, surgical technique, and appropriate use of mesh prosthetics and peri-operative antibiotics.

Clinical Significance

Abdominal wall defects are quite common and can be very complex. Knowledge of pertinent anatomy, preoperative optimization, techniques for repair, mesh use, and potential complications will allow the surgeon to deal with these difficult clinical problems.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of abdominal wall defects is challenging and complex. While once the domain of the general surgeon, today it is realized that reconstruction of the abdominal wall may also require the expertise of a plastic surgeon. To achieve optimal outcomes, the goals and objectives of the abdominal wall reconstruction have to be defined and thoroughly discussed with the patient before taking the patient to surgery. In some cases, chronic infection may preclude definitive repair in a single stage, consultation with an infectious disease specialist may be prudent. As with any other complex procedure, the preoperative workup must be thorough, and the patient should be seen by a pulmonologist and cardiologist to optimize lung and cardiac function if any underlying cardiopulmonary disease is present. Because of the potential risk of injury to the bowel, bowel preparation is recommended. If an enterotomy occurs during surgery, prompt consultation from a general or colorectal surgeon is appropriate.[9]

To improve outcomes, the Ventral Hernia Working group has developed a 4-tier grading system based on the risk of a surgical site complication.[10] However, evidence-based guidelines regarding the best approach for abdominal wall reconstruction are not available because of the heterogeneity in technique, types of sutures used, different prosthetic material, lack of long-term follow up and patient characteristics. While studies show that the laparoscopic approach may have a better outcome compared to the open approach, the former is also associated with a high rate of bowel injury and conversion to an open procedure, leading some surgeons to question the validity of those conclusions.

In the postoperative period, the role of the nurse and pharmacist is critical. The patients have to be monitored for pain, wound infection, fistula formation, and a variety of common postoperative complications such as atelectasis, deep vein thrombosis, ileus, and pain. The pharmacist may be involved in parenteral nutrition if a complication has resulted. With each attempt at reconstruction, there is a 10% to 20% risk of recurrence; it is best to optimize the patient in every way possible prior to any attempt at repair to minimize the need for a revision procedure. This further emphasizes the need for an multi-disciplinary team approach to the management of complex abdominal reconstructions. [11] [Level A]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kapur SK, Butler CE. Lateral Abdominal Wall Reconstruction. Seminars in plastic surgery. 2018 Aug:32(3):141-146. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1666801. Epub 2018 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 30046290]

Fortelny RH. Abdominal Wall Closure in Elective Midline Laparotomy: The Current Recommendations. Frontiers in surgery. 2018:5():34. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2018.00034. Epub 2018 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 29876355]

Muneer M, Badran S, Zahid R, Abdelmageed A, AlDulaimi MM. Recurrent Desmoid Tumor with Intra-Abdominal Extension After Abdominoplasty: A Rare Presentation. The American journal of case reports. 2019 Jul 4:20():953-956. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.916227. Epub 2019 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 31270310]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMericli AF. Management of the Open Abdomen. Seminars in plastic surgery. 2018 Aug:32(3):127-132. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1666802. Epub 2018 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 30046288]

Birolini C, de Miranda JS, Utiyama EM, Rasslan S, Birolini D. Active Staphylococcus aureus infection: Is it a contra-indication to the repair of complex hernias with synthetic mesh? A prospective observational study on the outcomes of synthetic mesh replacement, in patients with chronic mesh infection caused by Staphylococcus aureus. International journal of surgery (London, England). 2016 Apr:28():56-62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.02.062. Epub 2016 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 26912016]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRamirez OM, Ruas E, Dellon AL. "Components separation" method for closure of abdominal-wall defects: an anatomic and clinical study. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1990 Sep:86(3):519-26 [PubMed PMID: 2143588]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRazavi SA, Desai KA, Hart AM, Thompson PW, Losken A. The Impact of Mesh Reinforcement with Components Separation for Abdominal Wall Reconstruction. The American surgeon. 2018 Jun 1:84(6):959-962 [PubMed PMID: 29981631]

Warren JA, Love M. Incisional Hernia Repair: Minimally Invasive Approaches. The Surgical clinics of North America. 2018 Jun:98(3):537-559. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2018.01.008. Epub 2018 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 29754621]

Khansa I, Janis JE. Abdominal Wall Reconstruction Using Retrorectus Self-adhering Mesh: A Novel Approach. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2016 Nov:4(11):e1145 [PubMed PMID: 27975037]

Earle D, Roth JS, Saber A, Haggerty S, Bradley JF 3rd, Fanelli R, Price R, Richardson WS, Stefanidis D, SAGES Guidelines Committee. SAGES guidelines for laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Surgical endoscopy. 2016 Aug:30(8):3163-83. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5072-x. Epub 2016 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 27405477]

Sosin M, Patel KM, Albino FP, Nahabedian MY, Bhanot P. A patient-centered appraisal of outcomes following abdominal wall reconstruction: a systematic review of the current literature. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2014 Feb:133(2):408-418. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000436860.47774.eb. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24150119]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence