Introduction

Although the earliest reported use of mechanical ventilation was in the 16th century, it was not employed more widely until the 20th century, when it was given more consistently to patients with respiratory failure. Strong clinical evidence supporting optimal respiratory care and ventilator support has accumulated over decades.

Numerous methods for ventilating patients are available in both invasive and noninvasive modes. However, patient-ventilator asynchrony has been a persistent problem.[1][2][3] Patient-ventilator asynchrony occurs when the ventilator fails to detect the patient's breath or detects it too late in the breathing cycle, leading to complications that include increased sedation, discomfort, and possibly higher morbidity and mortality.[4][5][6] Additionally, invasive mechanical ventilation causes alveolar overdistention, pulmonary air leaks, and small airway injuries.[7]

Sinderby et al first described the concept of neural control of mechanical ventilation in 1999. The neurally adjusted ventilatory assist (NAVA) equipment detects the diaphragm's electrical activity or electromyographic signal by a specially placed orogastric or nasogastric catheter, which can reduce asynchrony and provide increased comfort and control of ventilation to patients. This mode may be used invasively and noninvasively, as in noninvasive ventilation-neurally adjusted ventilatory assist (NIV-NAVA).

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Normal Respiration

The respiratory center in the brain activates spontaneous breathing via the transmission of impulses through the phrenic nerve. Lourenco et al showed that diaphragmatic activity is proportional to phrenic nerve activity.[8] This phrenic nerve signal leads to muscle contraction and allows air inflow by creating a negative alveolar pressure. Phrenic nerve impulses precede the contraction of the diaphragm. A breath's cycling depends on the respiratory center output.

Physiological Basis for Increased Synchrony

Three trigger variables are primarily used in modern mechanical ventilators: pressure, flow, and time. Pressure-triggered ventilation, the first and simplest technique developed, involves setting a trigger threshold measured in cm H2O. The ventilator will initiate a breath when the baseline pressure drops by that amount (eg, the patient is attempting an inspiration). In time-triggered ventilation, the ventilator will initiate a new breath at set intervals regardless of the patient's efforts. In spontaneously breathing patients, this mechanism is primarily used during airway pressure release ventilation.

In contrast, flow-triggered ventilation involves sensing a decrease in flow before initiating a breath. Most modern ventilators use this mechanism for traditional pressure and volume ventilation, as it theoretically allows the patient to be more comfortable with minimal effort required to trigger the ventilator. However, both pressure and flow triggering occur at the end of the breath, after the patient has already decided to initiate a breath—following diaphragm contraction when pressure and flow change. This delay can be significant in some patients. Additionally, further challenges with detection may arise, particularly for neonates, as most neonatal intensive care units use uncuffed endotracheal tubes, and the resultant leakage makes it more difficult to detect a breath.

One can think of NAVA as another form of trigger that is theoretically more physiological. During NAVA, a nasogastric or orogastric tube with electrodes is placed in the patient to detect changes in the diaphragm's electrical activity (Edi) more than 60 times per second. The diaphragm contracts as the phrenic nerves deliver the signal to breathe. The ventilator measures the strength of this activity and provides an appropriately sized breath based on the patient's own effort. NAVA is theoretically superior to conventional triggering methods, as respiration is directly guided by the activity of the patient's central nervous system rather than external flow or pressure sensors. This process reduces dyssynchrony, as the trigger variable is more direct and occurs earlier in the patient's breathing cycle.

Signal Generation Based on the Electrical Activity of the Diaphragm

Electrical activity from nerve impulses stimulates skeletal muscle contraction. The NAVA ventilator uses this electrical activity to assist the patient in a synchronized manner. Edi is the primary signal required for NAVA to function and serves as the leading source for ventilator triggers. In theory, NAVA overcomes the limitations of proportional assist ventilation, such as air leaks and asynchrony between the patient and the ventilator. The ventilator breath is triggered and terminated by changes in this electrical activity. Pressure is delivered in proportion to the Edi signal and ends when the Edi signal subsides. The ventilator displays 2 forms of Edi: Edi max, signifying peak inspiration, and Edi min, indicating tonic diaphragm activity.[9]

Neurally Adjusted Ventilatory Assist Level

The NAVA level converts the Edi signal into the appropriate pressure and is expressed in cm H2O/µV. During ventilation, the ventilator delivers pressure by multiplying the Edi by the NAVA level. Increasing or decreasing the NAVA level alters the pressure delivery for the same Edi. However, pressure delivery varies with each breathing effort and depends on the measured electrical activity of the diaphragm. Hence, the patient controls both their own and the ventilator’s pressure, which improves synchrony and comfort.

The peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) is calculated using the following formula:

PIP = [NAVA level x (Edi max – Edi min)] + PEEP

Indications

NAVA may be used in all conditions where conventional invasive or noninvasive ventilators are indicated. These conditions differ for adults and pediatric patients.

Adults

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- Acute hypoxemic respiratory failure [10]

Neonates or Children

- Respiratory distress syndrome

- Primary or secondary pulmonary hypertension

- Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), especially when asynchrony arises

- Central hypoventilation syndrome, which requires the continuous assessment of breathing activity [11]

Contraindications

Central and peripheral conditions that limit the respiratory drive, as well as diaphragmatic anatomical defects in patients with an intact respiratory drive, comprise the contraindications to NAVA. Examples are the following:

- Central disorder: paralytic drug use, respiratory drive suppression due to heavy sedation or brain injury

- Peripheral disorder: phrenic nerve injury, paralytic agent administration

- Structural (anatomical) disorder: esophageal atresia, diaphragmatic hernia

The NAVA catheter is also not compatible with magnetic resonance imaging machines, making the intervention unsuitable for patients undergoing this diagnostic modality.

Equipment

The Servo ventilator is the only ventilator compatible with the NAVA catheter, which comes in various sizes and should be appropriately selected based on the patient's size and weight. Choosing a catheter with the appropriate size is essential, as one that is too large or too small may not be able to pick up the Edi signal appropriately due to the positioning of the electrodes and the interelectrode width.

Personnel

A skilled respiratory therapist must set up the machine. A nurse should insert the Edi catheter. The provider stays at the bedside to position the catheter, troubleshoot signal issues, and select the correct initial settings.

Preparation

Personnel must insert and verify the proper Edi catheter position. The machine must be checked for proper functioning.

Technique or Treatment

An array of 9 miniaturized electrodes is embedded within a catheter positioned in the lower esophagus at the level of the diaphragm. These electrodes continuously detect the diaphragm's electrical activity and transmit this information to the ventilator.

The following are the 3 steps for proper Edi catheter positioning:

- Anatomical placement. The most common practice for placing a catheter is to measure the distance from the nose to the ear lobe to the xiphoid process (NEX method). Lubricants are not recommended, as they may interfere with the measurement of the Edi signal. However, Edi catheters may be dipped in water in place of lubricants.

- Verification of the electrode's position. Electrocardiogram (ECG) waveforms are visualized in the “Edi catheter positioning” window of the ventilator. The P and QRS waves should be seen in the top electrodes, which are positioned near the right atrium. Loss of the P wave and a dampened QRS wave should appear in the lower electrodes, which are placed near the stomach.

- Verification of the Edi signal. A weak or absent signal may suggest a neural disorder, sedation, or muscle relaxant use.

The catheter must be secured once the 2nd and 3rd leads are highlighted in blue. The insertion must be recorded.

Initial Neurally Adjusted Ventilatory Assist Settings

Initial NAVA settings include the following:

- NAVA level

- Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)

- Trigger Edi

- Backup ventilator settings

- Apnea Time

- Fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2)

- Alarm settings [12]

These settings are discussed in more detail below.

Neurally Adjusted Ventilatory Assist Level

The NAVA level should be set to achieve an Edi range of 5 to 20 µV. If the Edi max is less than 5 µV, the NAVA level should be decreased. If the Edi max exceeds 20 µV, the NAVA level should be increased. NAVA adjustments are typically made in increments of 0.1 to 0.2 cm H2O/µV. NAVA levels should generally fall between 0.5 and 3.0 cm H2O/µV, with exceptions. The goal is to adjust the NAVA level to ensure an appropriate Edi peak.

Since Edi peak reflects the work of breathing, the NAVA level balances the patient's effort with ventilator support. The aim is to allow the patient to breathe independently with appropriate effort. Most centers titrate NAVA levels to achieve an Edi peak between 10 and 15 µV. If the Edi peak is higher, the NAVA level should be increased to provide more support. If it is lower, the level should be reduced to encourage more patient effort.

Excessive support with low Edi peaks may weaken the breathing muscles and contribute to apnea in neonates. Studies suggest that setting the NAVA level to 0 in noninvasive mode may be beneficial for neonates. This mode, called "neurally adjusted ventilatory assist with positive airway pressure" (NAVA-PAP), primarily provides continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). When the patient becomes apneic, the backup ventilator settings automatically deliver a rate and a PIP.[13]

Positive End-Expiratory Pressure

PEEP mainly determines oxygenation and lung expansion. The same PEEP should be set according to earlier ventilator settings or determined based on the patient's age and the physiology of the underlying disease.

Trigger From Diaphragm Electrical Activity

The trigger Edi should initially be set to 0.5 µV. However, this parameter must be closely monitored and adjusted as needed. Setting the trigger Edi too low can lead to "over-triggering," where the patient initiates tiny, ineffective breaths. For example, if the Edi min is 5 µV, and the trigger is set to 0.5 µV, the ventilator may initiate a breath based on normal diaphragm variation, creating 2 problems. First, the patient receives an inadequate breath with a very small PIP due to the low Edi peak. Second, this event resets the apnea timer, preventing the ventilator from entering backup mode if the patient is truly apneic, as the ventilator detects a patient-initiated breath.

On the other hand, setting the Edi too high can cause asynchrony if the patient tries to breathe and the ventilator does not deliver the appropriate breath, leading to discomfort and other asynchrony-related problems. As with all settings, the trigger Edi should be continuously adjusted to match the patient’s current condition.

Backup Ventilator Settings

Appropriate ventilator settings should be chosen based on respiratory rate, PEEP, tidal volume, inspiratory time, and PIP and may be similar to the earlier ventilator settings. The backup settings are activated if a lack of Edi signal triggers a NAVA breath.

Apnea Time

Apnea time refers to the period during which the ventilator waits for the patient's breath before initiating backup ventilator settings. The ventilator may sense apnea, correctly or incorrectly, in the presence of the following:

- Patient issues, eg, the patient is not breathing

- Catheter issues, eg, the catheter is malpositioned

- Interference, eg, from the ECG leads

- Inappropriate Edi trigger setting, eg, the Edi is set too high

No well-established data exist on the appropriate apnea time setting, particularly in neonates. However, some crossover studies have shown that in NIV-NAVA, neonates with a short apnea time (2-3 seconds) experience fewer clinically significant bradycardia and hypoxia events than those with a longer apnea time (5 seconds). However, this study was conducted only for 2 hours for each group, and the long-term effects of short versus long apnea times remain unclear.[14]

Fraction of Inspired Oxygen

Oxygen requirements should be adjusted based on the targeted oxygen saturations. This adjustment depends on the status of the disease.

Alarm Settings

The maximum pressure should be chosen according to gestational age and maturity to provide reasonable support while avoiding barotrauma. The ventilator will attempt to limit the PIP to 10 cm H2O below the set alarm PIP. Generally, a maximum alarm limit of 30 to 35 cmH2O is effective in most neonates, though adjustments may be made depending on the underlying physiology.

Monitoring During Neurally Adjusted Ventilatory Assist Ventilation

Effective monitoring during NAVA ventilation is essential to assess the patient's respiratory status and ensure appropriate support. The following parameters should be regularly monitored:

- Oxygen saturation

- Transcutaneous carbon dioxide pressure

- Edi signal

- Arterial or capillary blood gas

Monitoring ventilator Edi signal trends is crucial. Tracking Edi peaks over time can indicate the patient's work of breathing, highlighting any improvement or worsening in respiratory status.

Continuous observation of the trends in the ventilatory parameters provides insight into the patient's respiratory condition. The number of switches to backup per minute indicates how often the patient goes into backup mode. If the numbers are higher, the patient may be going apneic and may not be ready to be weaned. The % time in backup mode is also essential. If patients remain mostly in backup ventilation, they may not be ready to be weaned.

Weaning From Neurally Adjusted Ventilatory Assist Ventilator

Unlike in pressure-assist ventilation, weaning happens spontaneously in NAVA.[15] Arterial or capillary blood gas analysis is an important tool for monitoring ventilator requirements. NAVA ventilator weaning is achieved by adjusting the NAVA level. If the blood gas levels are acceptable, the NAVA level must be weaned in increments of 0.5 to 1 cm H2O/µV. Extubation must be considered once the NAVA level reaches 1 cm H2O/µV. If the patient appears clinically stable, increasing apnea time, decreasing backup settings, or lowering the NAVA level must be considered before extubation.

Troubleshooting During Neurally Adjusted Ventilatory Assist

When a patient develops respiratory distress or begins to require increasing amounts of oxygen while on NAVA, troubleshooting should address potential mechanical or physiological issues. One common problem is catheter malpositioning. While NAVA catheters may be secured like other nasogastric or orogastric tubes, neonates, due to their normal anatomy, may require a tool similar to endotracheal tube holders to prevent frequent displacement.

Signal interference is another concern, particularly from ECG leads, which may disrupt accurate readings. Upper airway obstructions or changes in underlying physiology may also lead to pressure limits being exceeded. Adjustments may be necessary to accommodate these changes.

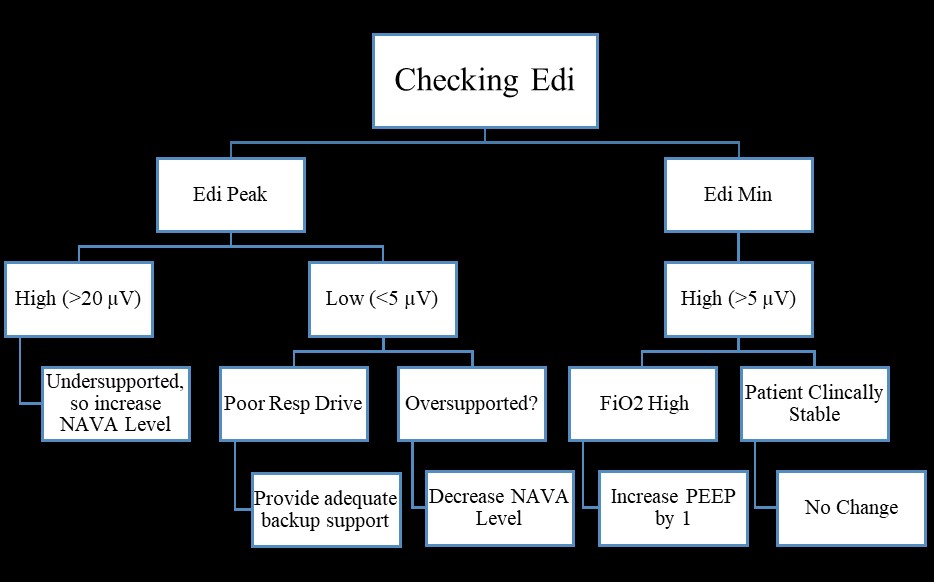

High Edi values may indicate undersupported ventilation, insufficient backup pressure, or inadequate ventilatory assistance. Monitoring the Edi signal and trends can help identify these issues (see Image. Diaphragmatic Electrical Activity Monitoring and Troubleshooting). In cases where backup pressure or settings are insufficient, adjusting these parameters can prevent further complications.

Careful attention to these factors, along with regular monitoring, can help mitigate complications and ensure the ventilator is functioning optimally.

Complications

NAVA ventilation mode does not have specific complications. However, this intervention can cause sequelae like other mechanical ventilator modes, including ventilator-induced lung injury, ventilator-induced diaphragmatic dysfunction, ventilator-associated pneumonia, and pneumothorax. The likelihood of ventilator-induced lung injury and ventilator-induced diaphragmatic dysfunction is reduced with NAVA, as pressure delivery is proportional to the patient's efforts, and studies have reported a lower need for PIP when using this mode.

Clinical Significance

As mentioned, NAVA aims to overcome the limitations of proportional-assisted ventilation. While additional studies are needed, NAVA has shown several potential benefits.

- Patient-ventilator synchrony: Mechanical ventilator synchrony depends on the timing of mechanical breath delivery and the amount of pressure provided by the ventilator. A delay often occurs between diaphragm activity, signaled by the brain, and ventilator response in flow-trigger ventilators. In contrast, NAVA delivers mechanical breaths as soon as the diaphragm receives a signal from the brain. Studies by Beck et al and Breatnach et al reported improved patient-ventilator synchrony during NAVA trials in infants and children. Enhanced synchrony reduces discomfort and agitation while improving ventilation and oxygenation.[16][17] Synchronized respiratory efforts are associated with better outcomes, including reduced lung injury from barotrauma and volutrauma, as well as decreased requirements for sedating agents, such as opioids.

- Air leaks: Air leaks are common in both invasive and noninvasive ventilation. Properly sizing endotracheal tubes, whether cuffed or uncuffed, and using ventilators with compensating circuits can help minimize leaks. However, leaks are often a greater challenge in noninvasive ventilation. NAVA has been shown to trigger effectively even with significant air leaks, as it does not rely on a flow sensor to detect a breath.[18]

- Benefits in preterm infants: The use of NAVA has increased in recent years and has been studied extensively in both preterm and term infants. A study by Kallio et al compared NAVA with conventional ventilators in preterm infants between 28 and 36 weeks of gestational age. The study demonstrated lower PIP requirements in infants treated with NAVA but found no significant differences in secondary outcomes such as BPD, duration of mechanical ventilation, or pneumothorax.[19] In a multicenter retrospective review, NAVA achieved respiratory stability in 67% of infants with severe BPD.[20] These findings suggest that NAVA may be safely used in premature infants. However, a well-designed randomized controlled trial is needed to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of NAVA in reducing the incidence of BPD.

- Noninvasive mode: NIV-NAVA functions similarly to invasive NAVA, delivering ventilation through nasal prongs or a mask. Studies have shown that NIV-NAVA is effective even in settings with significant air leaks. Infants extubated to NIV-NAVA remained extubated longer and required lower PIP than those managed with noninvasive pressure ventilation.[21] The setup for NIV-NAVA and related monitoring techniques is the same as that of invasive NAVA.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Like other ventilation techniques, NAVA requires close coordination between physicians, registered nurses, and respiratory therapists for better management. Proper teaching and guidance are needed before its implementation in any intensive care unit. Although NAVA has shown some promising results in a few studies, more extensive research is required for its widespread use. Consistent monitoring, thorough documentation, and tracking of ventilator parameters are crucial for optimizing patient outcomes.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

The interprofessional team must be qualified to monitor both ventilator activity and the patient to identify and address complications promptly. For instance, frequent backup mode activation should prompt the team to alert the physician, as it may indicate clinical deterioration. Similarly, consistently rising or falling Edi peaks can signal changes in the patient’s work of breathing, necessitating adjustments to the NAVA level. Additionally, careful monitoring of the Edi catheter position is crucial, as malpositioning can compromise the effectiveness of this ventilation mode.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Diaphragmatic Electrical Activity Monitoring and Troubleshooting. This diagram summarizes the steps for monitoring equipment function and patients on neurally adjusted ventilatory assist (NAVA) based on diaphragmatic electrical activity, along with troubleshooting potential problems.

Contributed by Sanket D Shah, MD

References

Keszler M. State of the art in conventional mechanical ventilation. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2009 Apr:29(4):262-75. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.11. Epub 2009 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 19242486]

Mellott KG, Grap MJ, Munro CL, Sessler CN, Wetzel PA. Patient-ventilator dyssynchrony: clinical significance and implications for practice. Critical care nurse. 2009 Dec:29(6):41-55 quiz 1 p following 55. doi: 10.4037/ccn2009612. Epub 2009 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 19724065]

Gonzalez-Bermejo J, Janssens JP, Rabec C, Perrin C, Lofaso F, Langevin B, Carlucci A, Lujan M, SomnoNIV group. Framework for patient-ventilator asynchrony during long-term non-invasive ventilation. Thorax. 2019 Jul:74(7):715-717. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-213022. Epub 2019 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 31028239]

Murias G, Lucangelo U, Blanch L. Patient-ventilator asynchrony. Current opinion in critical care. 2016 Feb:22(1):53-9. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000270. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26627539]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceThille AW, Rodriguez P, Cabello B, Lellouche F, Brochard L. Patient-ventilator asynchrony during assisted mechanical ventilation. Intensive care medicine. 2006 Oct:32(10):1515-22 [PubMed PMID: 16896854]

Subirà C, de Haro C, Magrans R, Fernández R, Blanch L. Minimizing Asynchronies in Mechanical Ventilation: Current and Future Trends. Respiratory care. 2018 Apr:63(4):464-478. doi: 10.4187/respcare.05949. Epub 2018 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 29487094]

Stein H, Alosh H, Ethington P, White DB. Prospective crossover comparison between NAVA and pressure control ventilation in premature neonates less than 1500 grams. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2013 Jun:33(6):452-6. doi: 10.1038/jp.2012.136. Epub 2012 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 23100042]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLourenço RV, Cherniack NS, Malm JR, Fishman AP. Nervous output from the respiratory center during obstructed breathing. Journal of applied physiology. 1966 Mar:21(2):527-33 [PubMed PMID: 5934459]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSinderby C, Navalesi P, Beck J, Skrobik Y, Comtois N, Friberg S, Gottfried SB, Lindström L. Neural control of mechanical ventilation in respiratory failure. Nature medicine. 1999 Dec:5(12):1433-6 [PubMed PMID: 10581089]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNavalesi P, Costa R. New modes of mechanical ventilation: proportional assist ventilation, neurally adjusted ventilatory assist, and fractal ventilation. Current opinion in critical care. 2003 Feb:9(1):51-8 [PubMed PMID: 12548030]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSzczapa T, Beck J, Migdal M, Gadzinowski J. Monitoring diaphragm electrical activity and the detection of congenital central hypoventilation syndrome in a newborn. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2013 Nov:33(11):905-7. doi: 10.1038/jp.2013.89. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24169930]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSindelar R, McKinney RL, Wallström L, Keszler M. Proportional assist and neurally adjusted ventilation: Clinical knowledge and future trials in newborn infants. Pediatric pulmonology. 2021 Jul:56(7):1841-1849. doi: 10.1002/ppul.25354. Epub 2021 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 33721418]

Protain A, Firestone K, Hussain S, Lubarsky D, Stein H. Evaluation of NAVA-PAP in premature neonates with apnea of prematurity: minimal backup ventilation and clinically significant events. Frontiers in pediatrics. 2023:11():1234964. doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1234964. Epub 2023 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 37868266]

Morgan EL, Firestone KS, Schachinger SW, Stein HM. Effects of Changes in Apnea Time on the Clinical Status of Neonates on NIV-NAVA. Respiratory care. 2019 Sep:64(9):1096-1100. doi: 10.4187/respcare.06662. Epub 2019 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 31164483]

Narchi H, Chedid F. Neurally adjusted ventilator assist in very low birth weight infants: Current status. World journal of methodology. 2015 Jun 26:5(2):62-7. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v5.i2.62. Epub 2015 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 26140273]

Breatnach C, Conlon NP, Stack M, Healy M, O'Hare BP. A prospective crossover comparison of neurally adjusted ventilatory assist and pressure-support ventilation in a pediatric and neonatal intensive care unit population. Pediatric critical care medicine : a journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies. 2010 Jan:11(1):7-11. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181b0630f. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19593246]

Donn SM, Sinha SK. Can mechanical ventilation strategies reduce chronic lung disease? Seminars in neonatology : SN. 2003 Dec:8(6):441-8 [PubMed PMID: 15001116]

Beck J, Reilly M, Grasselli G, Mirabella L, Slutsky AS, Dunn MS, Sinderby C. Patient-ventilator interaction during neurally adjusted ventilatory assist in low birth weight infants. Pediatric research. 2009 Jun:65(6):663-8. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819e72ab. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19218884]

Kallio M, Koskela U, Peltoniemi O, Kontiokari T, Pokka T, Suo-Palosaari M, Saarela T. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist (NAVA) in preterm newborn infants with respiratory distress syndrome-a randomized controlled trial. European journal of pediatrics. 2016 Sep:175(9):1175-1183. doi: 10.1007/s00431-016-2758-y. Epub 2016 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 27502948]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMcKinney RL, Keszler M, Truog WE, Norberg M, Sindelar R, Wallström L, Schulman B, Gien J, Abman SH, Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia Collaborative. Multicenter Experience with Neurally Adjusted Ventilatory Assist in Infants with Severe Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. American journal of perinatology. 2021 Aug:38(S 01):e162-e166. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1708559. Epub 2020 Mar 24 [PubMed PMID: 32208500]

Makker K, Cortez J, Jha K, Shah S, Nandula P, Lowrie D, Smotherman C, Gautam S, Hudak ML. Comparison of extubation success using noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) versus noninvasive neurally adjusted ventilatory assist (NI-NAVA). Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2020 Aug:40(8):1202-1210. doi: 10.1038/s41372-019-0578-4. Epub 2020 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 31911641]