Introduction

FDA recalls have a significant financial toll on the healthcare system. Clinically important drug recalls occur approximately once per month in the United States. Illustrating the financial cost of recalls, Johnson and Johnson lost approximately $600 million in sales after closing a distribution site due to a recall. Moreover, the toll on human life has been substantial. A striking example is the New England Compounding Center recall of injectable corticosteroids contaminated with fungal strains. The product caused 751 reported cases of fungal meningitis and 64 deaths. Historically, this incident was significant: it triggered a transfer of regulatory authority over compounded products from state pharmacy boards to the FDA.[1]

Another infamous recall occurred in 2012 when Pfizer recalled approximately 1 million packs of birth control pills due to incorrect packaging.[2] The top recall causes are incorrect labeling, defective products, and incorrect potency. Common examples of contaminants that cause drug recalls were other drugs, heavy metals, bacteria, or fungi.

Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Function

Contrary to public perception, the FDA does not have the authority to mandate a drug's withdrawal from the market directly. Instead, the FDA can only request that a manufacturer recalls a drug. In the rare case that a manufacturer refuses to do so, then the FDA can force the manufacturer to recall the product by statute. This legal action is pursued via the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. An injunction is issued to halt further manufacture or distribution.[3][4] The FDA can directly and unilaterally demand the removal of medical devices, but it cannot do the same for medications.[5] However, both medical devices and medications are typically recalled by the manufacturers voluntarily. The FDA issues drug recalls—more precisely thought of as requests for drug recalls—through the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) and Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER).[1]

Drug recalls are grouped into class I, class II, or class III in order of decreasing severity. Class I recalls indicate the drug could potentially cause death. Class II recalls are the most common and indicate the drug product or device has reversible side effects or an exceedingly small probability of serious adverse effects. Class III recalls are due to innocuous defects in something such as container design.[1] A recent example of a class I recall involved implantable cardioverter defibrillators.[6] These devices prevent potentially fatal ventricular tachyarrhythmia.[7] Since a defect in these devices can cause death, it was a class I FDA recall. One example of class II recalls is radiation oncology devices. These have been subject to class II recalls due to faulty software that can temporarily cause the patient to be incorrectly positioned during their radiation therapy.[8]

Because this software defect only causes sporadic errors within a given treatment session, this is a class II recall. Class III recalls are the most benign. These are primarily products that are extremely unlikely to cause any harm to patients, but they violate FDA standards for packaging, labeling, documentation, etc. For example, if a drug is produced, labeled, and distributed safely and correctly, but a small detail in one of these steps was not documented, the FDA may request a class III recall out of an abundance of caution. In addition to medications, medical devices and vaccines are also under the FDA’s regulatory purview and thus subject to recall. In addition to the aforementioned implantable cardioverter defibrillators, recent examples of recalled medical devices include radiology equipment, ophthalmology devices, and orthopedic devices.[9][10][11]

Clinical Significance

Vaccines, a topic with renewed salience due to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, are another medical product regulated by the FDA and known to have potential adverse reactions. Together with the CDC, the FDA operates the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). This system relies on voluntary reporting from healthcare providers to analyze post-licensure vaccine safety. Clinical trials evaluated by the FDA to grant licensure to a vaccine are rigorous and thorough, and they detect most complications. However, when a vaccine is administered on a larger scale, the expanded sample size and the ability for longer-term follow-up allow for the detection of adverse events not initially seen in clinical trials. For this reason, providers should report adverse vaccine reactions, however trivial they may seem. Although more mild reactions are reported voluntarily, per VAERS policy, healthcare providers must report any adverse event that might prohibit further dosing in the affected patient.[12]

Even though it is not mandatory to report mild adverse reactions, doing so generates data useful to future public health research. As a dynamic database, VAERS generates nearly real-time statistics regarding adverse vaccine events. This dataset offers providers a prompt and economical means of analyzing vaccine safety. VAERS provides a rich data source that can be used in retrospective studies, sometimes leading to recall. One prominent example involved a new vaccine for Lyme disease. In 2001, an FDA panel convened to analyze purported associations between this vaccine and inflammatory arthritis. While they found no significant statistical correlation, their investigation prompted deeper statistical analysis of previously obtained VAERS data regarding the vaccine’s adverse reactions.[13]

VEARS reporting has been instrumental in recording adverse events associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccines. Although extremely rare, cases of anaphylaxis following the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine have been reported.[14] The rate of anaphylaxis following the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine was reported as 11.1 per million doses administered. Like drugs and medical devices, vaccines can be recalled as well. A notable example occurred with a vaccine against Lyme disease.[13] The case studies with Lyme Disease and the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine were only possible due to VAERS data contributed by willing healthcare providers, highlighting the positive impact providers can have on public health simply by reporting adverse events observed clinically. Joint efforts reporting to VAERS give all healthcare professionals more accurate data to predict adverse effects they can expect to observe clinically.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Healthcare providers, including pharmacists, must understand their legal and professional responsibilities regarding recalls. Pharmacists are strongly encouraged, but not required by law, to report adverse drug reactions to the FDA. With certain vaccines, however, there is a legal obligation.[15] Providers play a key role in improving public health when they opt to report adverse events. By educating themselves about potential adverse drug effects, monitoring them in patients, and reporting events to the FDA, pharmacists, and physicians protect public health. The scientific vetting process for new drugs is extremely rigorous in the United States; however, the system still relies on physicians to detect adverse reactions that might be undiscovered in clinical trials. Unfortunately, adverse reactions are underreported by clinicians.[15]

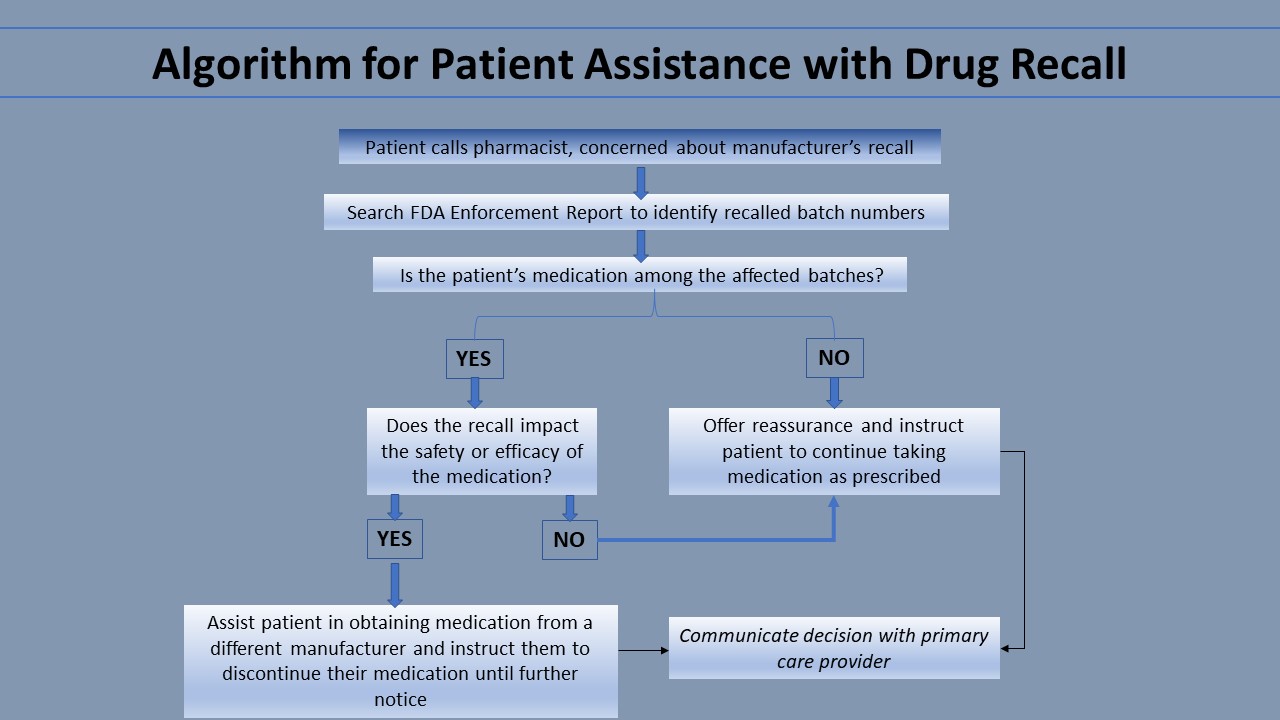

Drug manufacturers often notify consumers automatically of a recall before pharmacies are notified. Notices are sent to all consumers of the recalled medication without regard to specific batches affected. Thus, pharmacists should be prepared to answer patient questions concerning recalls. By comparing the batch number of a patient’s medication to the batch numbers involved in the recall, pharmacists can identify whether their specific patient’s medication was affected. The best resource for pharmacists to obtain the most current information regarding FDA recalls, including specific batch numbers affected, is the FDA Enforcement Report Index. This resource is free online and is updated weekly.

If a patient’s medication is among the affected batches, the pharmacist should learn the reason for the recall. If the recall is due to something benign—for example, the drug container has a defect that does not impact the chemical quality of the medication—the pharmacist should inform the patient of this and counsel them to continue taking the medication as usual. If the recall justifies the patient stopping their medication, the pharmacist can help them obtain their medication from another manufacturer. If a patient’s medication was not among the affected batches, the pharmacist can reassure the patient and counsel the patient to continue taking the medication as usual. This communication is vital because it prevents patients from needlessly stopping their medication. The pharmacist can also share their decision with the patient’s primary care provider to avoid future confusion. Another resource providers can direct their patients to is the FDA Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS). Consumers, pharmaceutical companies, and providers can all report complaints and adverse events to the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). This FDA maintains FAERS as a free, user-friendly system for online searching by the general public. Thus, it is a useful resource for patients.[1]

The Recall Alert System is a mechanism designed for the FDA to communicate with providers regarding recalls, but it frequently fails to do so. For 20% of Class I recalls (the most severe category of recalls), the FDA failed to utilize the Recall Alert System or MedWatch in one study. Rather than an exhaustive list of all available recall information, MedWatch is a summary of severe reactions that a provider would not anticipate based solely on current labeling. An adverse event is considered serious if it fatal, life-threatening, requires hospitalization, causes a congenital anomaly, or if medical or surgical intervention was needed to avoid permanent consequences.[15] This failure of reporting further emphasizes the importance of pharmacists consulting the FDA Enforcement Report Index.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Hall K, Stewart T, Chang J, Freeman MK. Characteristics of FDA drug recalls: A 30-month analysis. American journal of health-system pharmacy : AJHP : official journal of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2016 Feb 15:73(4):235-40. doi: 10.2146/ajhp150277. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26843501]

Wang B, Gagne JJ, Choudhry NK. The epidemiology of drug recalls in the United States. Archives of internal medicine. 2012 Jul 23:172(14):1109-10. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2013. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22664942]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDzanis DA. Anatomy of a recall. Topics in companion animal medicine. 2008 Aug:23(3):133-6. doi: 10.1053/j.tcam.2008.04.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18656840]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNagaich U, Sadhna D. Drug recall: An incubus for pharmaceutical companies and most serious drug recall of history. International journal of pharmaceutical investigation. 2015 Jan-Mar:5(1):13-9. doi: 10.4103/2230-973X.147222. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25599028]

. Medical device recall authority--FDA. Final rule. Federal register. 1996 Nov 20:61(225):59004-22 [PubMed PMID: 10163116]

Liu J, Brumberg G, Rattan R, Jain S, Saba S. Class I recall of defibrillator leads: a comparison of the Sprint Fidelis and Riata families. Heart rhythm. 2012 Aug:9(8):1251-5. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.04.003. Epub 2012 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 22484652]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAziz S, Leon AR, El-Chami MF. The subcutaneous defibrillator: a review of the literature. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014 Apr 22:63(15):1473-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.018. Epub 2014 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 24530663]

Connor MJ, Tringale K, Moiseenko V, Marshall DC, Moore K, Cervino L, Atwood T, Brown D, Mundt AJ, Pawlicki T, Recht A, Hattangadi-Gluth JA. Medical Device Recalls in Radiation Oncology: Analysis of US Food and Drug Administration Data, 2002-2015. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2017 Jun 1:98(2):438-446. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.02.006. Epub 2017 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 28463163]

Talati RK, Gupta AS, Xu S, Ghobadi CW. Major FDA medical device recalls in ophthalmology from 2003 to 2015. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 2018 Apr:53(2):98-103. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2017.08.001. Epub 2017 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 29631834]

Vajapey SP, Li M. Medical Device Recalls in Orthopedics: Recent Trends and Areas for Improvement. The Journal of arthroplasty. 2020 Aug:35(8):2259-2266. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.03.025. Epub 2020 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 32279947]

Day CS, Park DJ, Rozenshteyn FS, Owusu-Sarpong N, Gonzalez A. Analysis of FDA-Approved Orthopaedic Devices and Their Recalls. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2016 Mar 16:98(6):517-24. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.00286. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26984921]

Shimabukuro TT, Nguyen M, Martin D, DeStefano F. Safety monitoring in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). Vaccine. 2015 Aug 26:33(36):4398-405. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.07.035. Epub 2015 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 26209838]

Poland GA. Vaccines against Lyme disease: What happened and what lessons can we learn? Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2011 Feb:52 Suppl 3():s253-8. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq116. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21217172]

CDC COVID-19 Response Team, Food and Drug Administration. Allergic Reactions Including Anaphylaxis After Receipt of the First Dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine - United States, December 14-23, 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2021 Jan 15:70(2):46-51. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7002e1. Epub 2021 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 33444297]

Goldman SA, Kennedy DL. MedWatch: FDA's Medical Products Reporting Program. Postgraduate medicine. 1998 Mar:103(3):13-6 [PubMed PMID: 9519028]