Sonography 1st Trimester Assessment, Protocols, and Interpretation

Sonography 1st Trimester Assessment, Protocols, and Interpretation

Introduction

Ultrasonography is a commonly used tool to evaluate the status of pregnancy. Complications arising from pregnancy are frequently-encountered complaints in emergency departments (EDs) and prenatal clinics. Though home pregnancy tests are increasingly popular, some women may discover they are pregnant for the first time in the outpatient setting. In the United States, approximately one-third of pregnant patients utilize the ED at least once during their pregnancy.[1][2]

Pregnant women will typically have at least one ultrasound during their pregnancies. If only one ultrasound can be performed during pregnancy, it should be performed in the mid-second trimester (18 to 22 weeks) to detect fetal anomalies and growth abnormalities.[3][4] First trimester ultrasounds are not a requirement for all pregnancies to confirm viability.[5] However, if any high-risk features (advanced maternal age, twin pregnancy, etc.) or clinical concerns are present (irregular menses, vaginal bleeding, etc.), more than one ultrasound may be performed at the clinician's discretion, with the first ideally in the late first trimester between 10+0 and 13+6 weeks.[5] However, ultrasound exams before ten weeks are common and can still be used as accurate assessments for most necessary clinical determinations.[6]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The uterus is bordered by the bladder anteriorly and the rectum posteriorly. In most women, the uterus is anteverted, which indicates that the uterus is superior/posterior to the bladder and anterior to the rectum, with the uterine fundus more anteriorly oriented. Women may also have anteflexed, retroverted, retroflexed uterine orientations.[7]

The uterus has a hyperechoic stripe in the center of the fundus and communicates with the cervix. Distal to the cervix is the vaginal canal, which appears as a hyperechoic line when viewed with a transabdominal transducer.

In the adnexa to either side of the uterus, the right and left ovaries classically lie between the lateral uterine wall and the internal iliac vessels, a relationship more likely altered in multiparous women. The adnexa also includes the fallopian tubes connecting the uterus and ovaries, both of which should be carefully evaluated as they are the most likely locations of ectopic pregnancies.[8] Ovaries classically have a slightly hypoechoic echotexture compared to surrounding tissue and a "chocolate chip cookie" characteristic due to peripheral, anechoic follicles. Large corpus luteum cysts are commonly seen in early pregnancy, typically as a single large, simple cystic structure within ovarian tissue. Corpus luteum cysts involute as the placenta develops to support the growing fetus.

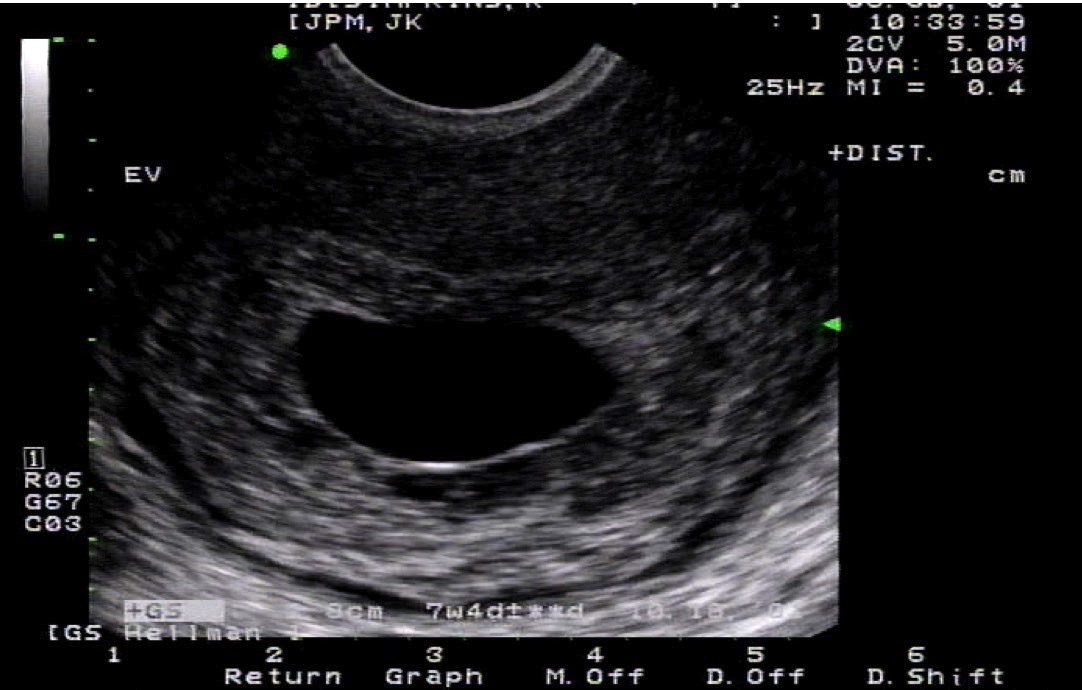

The first sign of intrauterine pregnancy is the gestational sac, an anechoic structure that appears between the fourth and fifth gestational weeks but is small at 2 or 3 mm in the greatest dimension.[8] Although not always seen, the double decidual sign is the first widely accepted sign of intrauterine pregnancy.[8][9] It is composed of two echogenic rings, the decidua capsularis (inner ring) and decidua vera (outer ring), which surround the developing gestational sac.[10][8] Because the double decidual sac sign may be confused with a pseudogestational sac (nonviable), many clinicians elect to visualize a yolk sac before confirming an intrauterine pregnancy. The yolk sac is typically visible by ultrasound in the fifth week and appears as a hyperechoic ring with an anechoic center located within the gestational sac.[8][11]

A fetal pole can be visualized in the sixth gestational week and appears as a hypoechoic structure immediately adjacent to the yolk sac.[8][11] By the sixth or seventh gestational week, fetal cardiac activity is usually evident.[8] In the seventh week, the amnion becomes sonographically visible and appears as a larger echogenic ring within the fetal pole's gestational sac.[11] The amnion expands after fetal urine production begins in the 10th week and fuses with the chorion by 14 to 16 weeks.[11]

Indications

First-trimester ultrasonography may be performed for a variety of reasons. Typical indications include pelvic pain, suspected ectopic pregnancy, suspected twin pregnancy, vaginal bleeding, suspected trophoblastic disease, assessment for fetal growth abnormalities, measurement of nuchal translucency, evaluation of pelvic masses or uterine abnormalities, and as an adjunct to chorionic villus sampling.[6][12] Asymptomatic patients in the first trimester may also be scheduled for a routine ultrasound when resources are available to establish an accurate gestational age.[4]

Vaginal bleeding is a common complaint during early pregnancy, affecting approximately 25% of patients, and maybe traumatic or non-traumatic in etiology.[13] A focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) examination should be performed when traumatic injuries are sustained in early pregnancy, or if patients are hypotensive, tachycardic, or have clinical signs concerning intraabdominal bleeding a FAST examination should be performed before the obstetric ultrasound.[8] If free fluid is found during the FAST exam in the trauma patient, immediate surgical management is warranted.[8] Likewise, if free fluid is seen during a FAST exam in a non-trauma, pregnant patient, ectopic pregnancy should be strongly considered.[8]

First-trimester ultrasonography may also be used to monitor the developing fetus. In certain health systems, screening for aneuploidy is performed using evaluations of nuchal translucency between 11+0 and 13+6 weeks gestation.[14][15] Ultrasonography may also be used to diagnose multiple gestations, rule out fetal anomalies, and monitor cardiac activity.[5]

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications to either transabdominal or transvaginal ultrasound in the 1st trimester, except for patient refusal. That said, performing providers should counsel patients on the limitations of a first-trimester ultrasound before conducting one.[5]

Equipment

When conducting a first-trimester ultrasound assessment, sonographers need a minimum of a two-dimensional ultrasound with the capability of adjustable power output, freeze, zoom, electronic calipers, and the ability to either store or print images to be saved.[5][12] The uterus and the pelvic organs require resolution at depth and necessitate a lower frequency bandwidth, for which the curvilinear transducer is well suited. A full bladder is ideal to accomplish the transabdominal exam. The distended bladder displaces the uterine fundus posteriorly, creating an acoustic window, enhancing the resolution of structures deep to the bladder. Occasionally, thin patients with anteverted uteri can have early pregnancies successfully evaluated transabdominally with a high-frequency, linear transducer but requires that the target depth is at or less than 6 cm.

If the transabdominal ultrasound is unsuccessful or further clarification of structures is needed, transvaginal ultrasound using an endocavitary transducer should be performed with a decompressed bladder. Endocavitary transducers should be covered in a clean sheath; ultrasound gel inside is either preloaded or manually loaded, and lubricating jelly is used exteriorly. Do not use ultrasound gel on the probe cover's exterior as it irritates mucous membranes. Following endocavitary examination, the used transducer must undergo high-level disinfection in accordance with local infection control, high-level disinfection standards. Cleaning wipes are insufficient for adequate disinfection.

Personnel

Physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, ultrasound technicians, and other providers trained in diagnostic obstetric ultrasonography may perform this exam.

Preparation

For the transabdominal ultrasound examination, place the patient in a position of comfort, supine, with the lower abdominal region exposed. The patient should have a full bladder for the transabdominal examination to maximize the visibility of the uterus and structures deep into the bladder. Tuck a towel into the waistband, and apply warmed ultrasound gel, if available, inferior to the umbilicus and superior to the pubic bone.

For a transvaginal ultrasound, ask the patient to empty her bladder before the start of the exam. An empty bladder allows the endocavitary probe to be as close as possible to the pelvic structures being evaluated, thus improving resolution and ease of evaluation. Using a bed with stirrups is ideal for patient positioning in the dorsal lithotomy position for ease of transducer movement. However, elevating the pelvis with towels or a bedpan may be adequate for examination and patient comfort. Endovaginal assessments require endocavitary transducer covers, either preloaded with gel or manually loaded with gel. Water-soluble lubricant should be used on the exterior of the transducer cover. As this is an invasive evaluation, a chaperone should be present for the duration of the examination.[16]

Technique or Treatment

To perform the transabdominal ultrasound, utilize the curvilinear probe and select the "obstetrics" setting. The obstetrics setting will load any requisite calculation and labeling packages needed to perform the complete evaluation. With the indicator oriented to the patient's head (midsaggital orientation), the transducer is superior to the pubic symphysis. The bladder is usually easily visualized when distended, filled with anechoic fluid in a triangular shape. Between the bladder and rectum lies the uterus with its hyperechoic endometrial stripe. Identify the uterine fundus and trace the hyperechoic endometrial stripe caudally to the cervix. Next, identify the hyperechoic vaginal stripe caudal to the cervix. Make note if the cervical os is open or closed and if any products of conception/tissue are lodged in the cervical canal Slide and fan the transducer completely through the uterus in the sagittal plane, moving from left to right or vice versa. Make a note of the borders of the uterus.

Rotate the transducer into the transverse plane to evaluate the pelvic structures in the short axis. With the probe marker to the patient's right slide, fan the probe superiorly and inferiorly, following the uterine fundus to the vaginal stripe behind the now square-shaped bladder. The transverse orientation is easiest to identify the ovaries due to the ease of finding the internal iliac vessels. Ovaries often lie between the internal iliac vessels and the uterus's lateral wall and can be found by fanning or sliding to the left and right of the uterus. Ovaries are hypoechoic, ovoid structures commonly seen with peripheral hypoechoic follicles.

A high-frequency linear probe may sometimes be used to evaluate the fetus in early pregnancy, as sometimes increased resolution is necessary for accurate evaluation. The maximum depth of the linear transducer is approximately 6cm, so patients must have a body habitus conducive to utilizing that transducer to be effective. An endovaginal ultrasound should be performed if a gestational sac cannot be adequately visualized by transabdominal exam.

As opposed to the transabdominal ultrasound, transvaginal ultrasound should be performed with an empty bladder. To complete the transvaginal ultrasound, utilize an endocavitary transducer with the "obstetrics" setting selected. Cover the transducer with a clean probe cover, ensuring the sheath is loaded with ultrasound gel before application. Use lubricating jelly only on the probe sheath's exterior as ultrasound gel irritates mucous membranes. With the indicator marker pointed to the ceiling, insert the probe into the vaginal canal until the decompressed bladder comes into view. As the endocavitary probe is inserted slightly farther, the bladder will disappear as the uterus appears. Similar to the transabdominal assessment, fan through the complete uterus in the sagittal plane. Ensure the cul-de-sac is visualized. Rotate the transducer 90 degrees to the coronal plane so that the indicator orients to the patient's right. Fan the transducer entirely through the uterus in the coronal plane. Evaluate the rectouterine pouch as well as both adnexa. The ovaries are best visualized during an endovaginal examination, typically located between the lateral uterine wall and the internal iliac vessels. Slight compression to either adnexa is often helpful in discerning ovarian tissue from surrounding structures.

If and when a gestational sac is visualized with or without an embryo or fetus, the sonographer must confirm it is within the uterus itself, as some ectopic pregnancies may lie adjacent to the uterus.[12] As discussed above, visualizing the double decidual sign is one way to confirm this.

The mean sac diameter (MSD) is the earliest method used to evaluate early pregnancy and requires using the sum of the length of the gestational sac (GS) + width of GS + depth of GS divided by 3. The first two measurements are taken in either the long or short axis and then the third measurement in the alternative axis. When measuring any cystic structure, such as a gestational sac, ensure that measurements capture all three dimensions, cranial-caudal, anterior-posterior, and right-left. A common mistake occurs by measuring the anterior-posterior distance (transabdominal) or cranial-caudal distance (transvaginal) twice. The sonographer can avoid this mistake by utilizing the "plus and minus sign" strategy when measuring the gestational sac in the two planes; use a "plus sign" to measure in the first plane and a "minus sign" only in the second.

If a fetal pole (embryo less than ten weeks) or fetus (greater than ten weeks) is visible, further gestational age estimations are obtained by either crown-rump length or biparietal diameter. In the first trimester, crown-rump length is the most accurate metric to determine gestational age.[4][12] The sonographer should optimize the image for this measurement by employing appropriate depth and zoom while maximizing the length of the fetal pole on the screen. Once optimized in the longest axis, freeze the image and measure crown-rump length with the electronic calipers, ensuring that the yolk sac is excluded from the measurement.[5] For the most accurate dating, several measurements should be taken and averaged.

Biparietal diameter may also be performed with similar accuracy to the crown-rump length between 12+0 and 13+6 weeks.[4] The image should be optimized to zoom on a symmetric, short axis of the fetal head.[5] The third ventricle, choroid plexus, and interhemispheric fissure must be in view for accurate assessment.[5] The measurement is taken across the broadest diameter from the inner wall to the outer wall of the cranium.[5]

Utilize either a 2-dimensional cine clip or M-mode to document fetal heart rate.[12] Optimize the image for M-mode by zooming in the image to maximize the fetal heartbeat on the screen. Place the M-mode line through the beating heart and measure either peak-to-peak or trough-to-trough. Some machines are preset to measure heart rate over a single beat-to-beat or the average of two or three beats. Considering that gated Doppler ultrasound is associated with higher energy output with potential adverse bioeffects, it should not be used during first-trimester assessments.[5][6][12] B-mode and M-mode have low energy outputs with the lowest risk of adverse bioeffects and thus are the only modes recommended for use in the first trimester.[5][6]

Complications

Discomfort, pelvic pain, vaginal bleeding, and infection are possible complications associated with first-trimester ultrasonography.

Clinical Significance

The most common reasons to perform first-trimester ultrasounds are establishing pregnancy location, viability, and accurate gestational age. An intrauterine gestational sac is indicative of an intrauterine pregnancy. Still, the presence of fluid alone in the uterus can be misleading if other structures, such as the yolk sac or fetal pole, are not visible.[5][12] If not definitively appreciated, follow-up ultrasound in 7 to 10 days with or without serial serum human chorionic gonadotropin measurement is the most appropriate action.[12]

Ectopic pregnancies are responsible for 6% of maternal deaths and must be ruled out with early pregnancy bleeding, pain, or signs of nontraumatic shock.[13]

In terms of pregnancy ultrasound, viability refers to an active embryo/fetus with a heartbeat at the time of the assessment.[5] An empty gestational sac with a mean sac diameter greater than 25 mm is diagnostic for a nonviable pregnancy.[11] Cardiac activity is often seen when the embryo is at, or greater than, 2 mm in size and indicates viability.[11] Conversely, a failed pregnancy can be diagnosed when a fetal pole measures seven or more centimeters without an evident heartbeat.[11] Lastly, pregnancy failure can be determined when two ultrasounds are performed at fixed intervals, typically 7 to 10 days, without evidence of an embryo.[13][11]

Pregnancy failure is suggested when the yolk sac diameter is greater than 7 mm, when the amnion is seen next to the yolk sac without an embryo and when the gestational sac is disproportionally small compared to the embryo (<5 mm difference).[11] Evidence of subchorionic hemorrhage, seen as an anechoic collection of fluid inside the uterine wall but outside of the gestational sac, is associated with higher pregnancy loss rates.[13]

Accurate gestational age is determined by early pregnancy ultrasound, which can reduce post-term pregnancy and induction rates.[4] Crown-rump length is the best measurement and has the lowest interoperator variability.[11]

Nuchal translucency is being evaluated as an additional tool to aid in the early discovery of fetal aneuploidy and other fetal abnormalities.[17][6]

Trophoblastic disease, also known as a molar pregnancy, is an uncommon but significant finding characterized by an intrauterine, echogenic mass with numerous internal cysts.[11] If these conditions are discovered or suspected, prompt gynecologic consultation is warranted.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Ultrasound technicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and physicians must coordinate care for pregnant patients. Understanding the life-threatening causes of maternal death in the first trimester is essential for all clinicians as this achieves the best possible outcome for pregnant women. With the advent of home-pregnancy tests, pregnant women often know their pregnancy status before seeking care for a pregnancy-related complaint. Unfortunately, a positive pregnancy test may be associated with a nonviable pregnancy, as well as a life-threatening condition.

A pregnant female who presents to the emergency department due to syncope, abdominal/pelvic pain, or any other concerning symptom will first be evaluated by the triage nurse and have their vitals taken. If hypotension is noted, this information, in addition to the positive pregnancy result, will be relayed to the on-site provider, which may be composed of a nurse practitioner, physician assistant, or emergency medicine physician. Prompt recognition by the provider that this may be a life-threatening cause is vital at this time. Point-of-care ultrasound may be performed at the bedside, potentially including a FAST exam, a transabdominal ultrasound, and even a transvaginal ultrasound. If findings concerning an ectopic pregnancy are noted, an obstetrician should be immediately consulted to consider prompt surgical management.[18] [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Malik S, Kothari C, MacCallum C, Liepman M, Tareen S, Rhodes KV. Emergency Department Use in the Perinatal Period: An Opportunity for Early Intervention. Annals of emergency medicine. 2017 Dec:70(6):835-839. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.06.020. Epub 2017 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 28811121]

Kilfoyle KA, Vrees R, Raker CA, Matteson KA. Nonurgent and urgent emergency department use during pregnancy: an observational study. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2017 Feb:216(2):181.e1-181.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.013. Epub 2016 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 27773714]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSalomon LJ, Alfirevic Z, Berghella V, Bilardo C, Hernandez-Andrade E, Johnsen SL, Kalache K, Leung KY, Malinger G, Munoz H, Prefumo F, Toi A, Lee W, ISUOG Clinical Standards Committee. Practice guidelines for performance of the routine mid-trimester fetal ultrasound scan. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology : the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011 Jan:37(1):116-26. doi: 10.1002/uog.8831. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20842655]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceButt K, Lim K, DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING COMMITTEE. RETIRED: Determination of gestational age by ultrasound. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology Canada : JOGC = Journal d'obstetrique et gynecologie du Canada : JOGC. 2014 Feb:36(2):171-181. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30664-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24518917]

Salomon LJ, Alfirevic Z, Bilardo CM, Chalouhi GE, Ghi T, Kagan KO, Lau TK, Papageorghiou AT, Raine-Fenning NJ, Stirnemann J, Suresh S, Tabor A, Timor-Tritsch IE, Toi A, Yeo G. ISUOG practice guidelines: performance of first-trimester fetal ultrasound scan. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology : the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013 Jan:41(1):102-13. doi: 10.1002/uog.12342. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23280739]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMei JY, Afshar Y, Platt LD. First-Trimester Ultrasound. Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America. 2019 Dec:46(4):829-852. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2019.07.011. Epub 2019 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 31677757]

Fidan U, Keskin U, Ulubay M, Öztürk M, Bodur S. Value of vaginal cervical position in estimating uterine anatomy. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2017 Apr:30(3):404-408. doi: 10.1002/ca.22854. Epub 2017 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 28192868]

Scibetta EW, Han CS. Ultrasound in Early Pregnancy: Viability, Unknown Locations, and Ectopic Pregnancies. Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America. 2019 Dec:46(4):783-795. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2019.07.013. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31677754]

Richardson A, Hopkisson J, Campbell B, Raine-Fenning N. Use of double decidual sac sign to confirm intrauterine pregnancy location prior to sonographic visualization of embryonic contents. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology : the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017 May:49(5):643-648. doi: 10.1002/uog.15966. Epub 2017 Apr 2 [PubMed PMID: 27194568]

Yeh HC. Use of the double decidual sac sign and intradecidual sign. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2011 Jan:30(1):119-20; author reply 120 [PubMed PMID: 21193714]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMurugan VA, Murphy BO, Dupuis C, Goldstein A, Kim YH. Role of ultrasound in the evaluation of first-trimester pregnancies in the acute setting. Ultrasonography (Seoul, Korea). 2020 Apr:39(2):178-189. doi: 10.14366/usg.19043. Epub 2019 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 32036643]

. AIUM-ACR-ACOG-SMFM-SRU Practice Parameter for the Performance of Standard Diagnostic Obstetric Ultrasound Examinations. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2018 Nov:37(11):E13-E24. doi: 10.1002/jum.14831. Epub 2018 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 30308091]

Hendriks E, MacNaughton H, MacKenzie MC. First Trimester Bleeding: Evaluation and Management. American family physician. 2019 Feb 1:99(3):166-174 [PubMed PMID: 30702252]

Rink BD, Norton ME. Screening for fetal aneuploidy. Seminars in perinatology. 2016 Feb:40(1):35-43. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2015.11.006. Epub 2015 Dec 25 [PubMed PMID: 26725144]

Hirshberg A, Dugoff L. First-trimester Ultrasound and Aneuploidy Screening in Multifetal Pregnancies. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2015 Sep:58(3):559-73. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000129. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26133496]

Ji C, Jiang X, Yin L, Deng X, Yang Z, Pan Q, Zhang J, Liang Q. Ultrasonographic study of fetal facial profile markers during the first trimester. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2021 Apr 24:21(1):324. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03813-6. Epub 2021 Apr 24 [PubMed PMID: 33894762]

Shakoor S, Dileep D, Tirmizi S, Rashid S, Amin Y, Munim S. Increased nuchal translucency and adverse pregnancy outcomes. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2017 Jul:30(14):1760-1763. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1224836. Epub 2016 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 27595799]

McRae A, Murray H, Edmonds M. Diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility of emergency department targeted ultrasonography in the evaluation of first-trimester pelvic pain and bleeding: a systematic review. CJEM. 2009 Jul:11(4):355-64 [PubMed PMID: 19594975]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence