Introduction

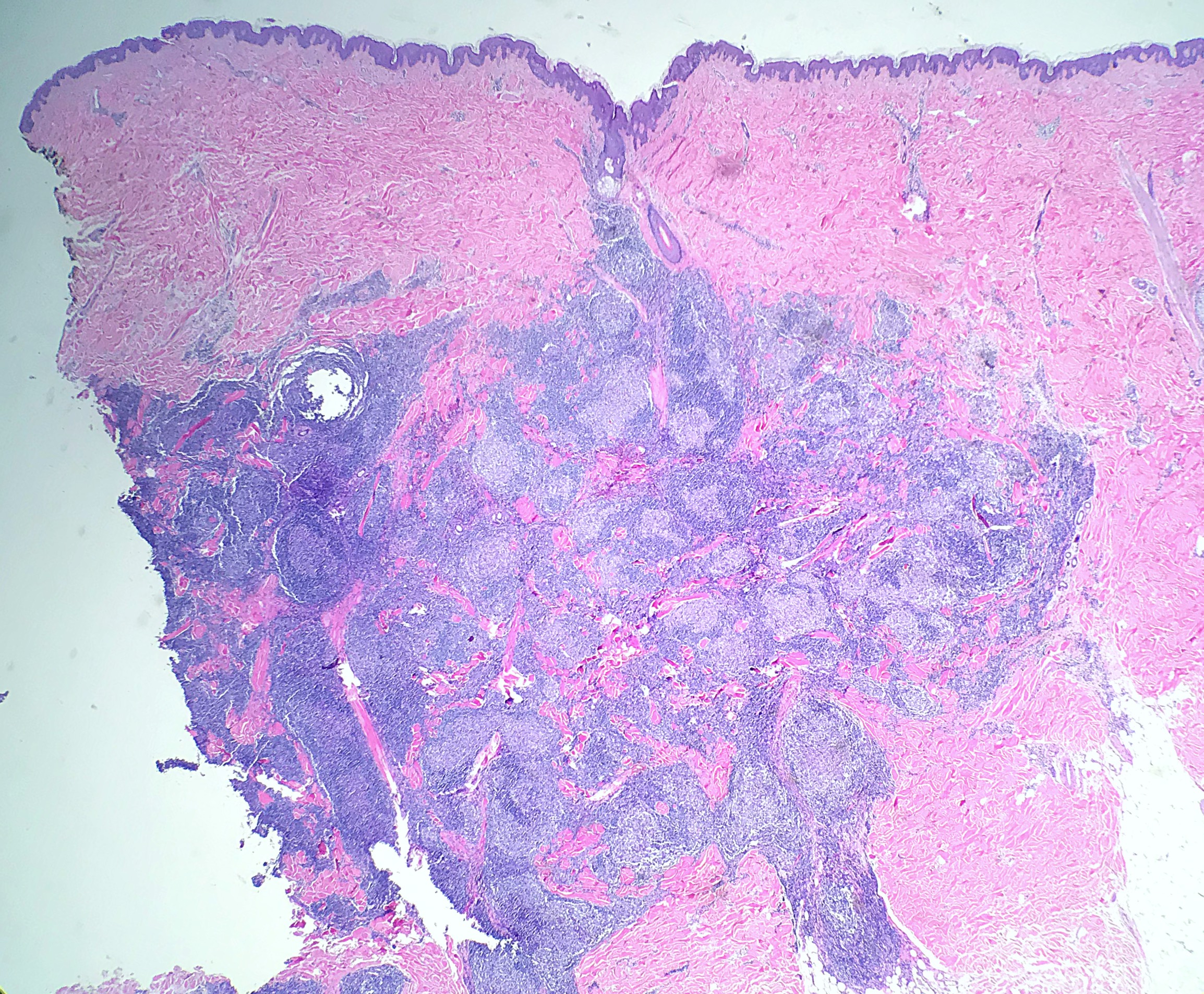

Several B-cell and T-cell lymphomas can affect the skin, most of which are T-cell lymphomas. Among primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas, primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL) is the most common. Primary cutaneous lymphomas are classified based on the involvement of the skin without evidence of systemic or nodal disease at the time of diagnosis (see Image. Primary Cutaneous Follicle Center Lymphoma, Biopsy). B-cell lymphomas, which make up 25% of cutaneous lymphomas, have a distinct clinical course and prognosis compared to histologically comparable systemic lymphomas.[1] PCFCL is a low-grade B-cell lymphoma made up of follicle center cells. It typically occurs on the head or trunk and has an excellent prognosis.[1][2][1][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

PCFCL is a low-grade lymphoma of follicle center B-cells, with no systemic or nodal involvement at diagnosis.[2]

Epidemiology

In the Western world, PCFCL is the most frequent cutaneous B-cell lymphoma and accounts for over 50% of cases. It usually affects middle-aged adults, predominance in men, with a man-to-woman ratio of 1.5 to 1.[3][4]

Pathophysiology

There are no definitive risk factors or identified hereditary predisposition for this disease. The pathogenesis is different from systemic or nodal follicular lymphoma.

Histopathology

Morphologically, PCFCL demonstrates perivascular and periadnexal to diffuse infiltration of monoclonal B-cells, which typically spares the epidermis (grenz zone). Growth patterns can be follicular, follicular diffuse, or diffuse. The growth pattern has not been found to be of clinical significance. The follicles in a follicular pattern PCFCL are commonly poorly defined, have an attenuated mantle zone, typically lack tingible body macrophages, and demonstrate a low rate of proliferation. The diffuse-type growth pattern frequently shows a sheet-like proliferation of monotonous centrocytes, which may have cleaved/multi-lobated/irregular nuclei. The proliferation rate of the diffuse growth pattern is generally high.[2][5]

History and Physical

PCFCL typically presents with solitary or grouped, firm to violaceous, painless, nonpruritic papules, plaques, or tumors. These frequently occur in the head, neck, and trunk.[2][6] The lesions are typically smooth and not ulcerated.[7] Although 60% of patients will have more than one lesion in a localized area, only a minority of patients (10%-20%) will have multifocal lesions.[2][8][9]

Evaluation

The diagnosis of PCFCL is made by histopathologic evaluation after a skin biopsy. The neoplastic cells stain positively for B-cell markers CD19, CD20, CD79a, and typically, the follicle center markers CD10 and BCL-6. CD21/23 can also help to highlight BCL-6 positive cells spreading beyond the regular meshwork. Commonly, PCFCL will be negative or weak for BCL-2. CD10 is variable and is ordinarily positive in a follicular pattern and negative in a diffuse pattern. CD5, CD43, IRF4/MUM1, and FOXP1 are negative. Ki67 can show a lower proliferation rate than regular reactive follicles.[2][10][11] Laboratory and imaging workup should include a complete blood count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, lactate dehydrogenase, and computed tomography (CT) with contrast, with or without positron emission tomography (PET) to exclude systemic involvement.[12][13]

Treatment / Management

Treatment is guided by the location of the lesions, the number, and the symptoms. PCFCL is effectively treated with local radiotherapy. Local radiation therapy is recommended for patients with single lesions or lesions in a single radiation field, with a complete response rate of 99% in a cumulative study review.[11] A dose of at least 30 Gray (Gy) is recommended with a margin of 1 to 1.5 cm. For small lesions, surgical excision is an acceptable alternative with a complete response rate of 99% but an increased rate of relapse (40% vs 30% for radiotherapy). For scattered or multiple lesions that can not be contained to one radiation field, local radiotherapy or observation is recommended for initial therapy. For very numerous or very thick lesions not amenable to radiotherapy, rituximab is suggested as a first-line systemic agent. If refractory, chemotherapy with R-CHOP and CHOP in older studies has been used. Fortunately, cutaneous relapses do not confer a worse prognosis and should be managed systematically with a similar approach to the initial diagnosis.[12][14](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The following are the differential diagnoses:

- Follicular lymphoma (FL)

- Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Leg type (PCDLBCL-LT)

- Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH)

- Primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma (PCMZL)

Systemic/nodal Follicular Lymphoma can secondarily involve the skin. Histology can be identical to PCFCL, but a strong expression of CD10 and BCL-2 should raise suspicion for secondary involvement of FL. Another clue to systemic FL is clinical presentations such as B symptoms and lymphadenopathy. Cytogenetics is also helpful, as t(14;18) is usually identified in FL but is not found in most cases of PCFCL.

PCDLBCL-LT is another lymphoma of large B-cells that classically involves the skin of the lower extremities of older women. However, 10-15% of cases present with non-leg lesions.[14] PCDLBCL-LT carries a much worse prognosis than PCFCL and requires a different treatment approach with multiagent chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy.[12] Histology of PCDLBCL-LT demonstrates a sheet-like proliferation of monotonous centroblasts/immunoblasts. It will strongly express BCL-2, MUM1, FOXP1, and IgM.

Skin biopsies of the head with RLH will have multiple follicles and can mimic PCFCL. Follicles in RLH will carry more of the traditional architecture with polarized germinal centers with light and dark zones, well-defined mantle zones, and tingible body macrophages. Immunohistochemistry can sometimes aid in diagnosis as BCL-6 positive cells will be well confined within the meshwork of the follicle defined by CD21/23. PCMZL with reactive follicles can also morphologically mimic PCFCL. Overall, PCMZL has a more heterogenous look with smaller, centrocyte-like, and monocytoid lymphocytes and light chain-restricted plasma cells. By immunohistochemistry, PCMZL will be positive for BCL-2 and sometimes CD43. It will be negative for BCL-6 and CD10.[2]

Prognosis

Overall, PCFCL has an excellent prognosis and follows an indolent course, with 5-year survival greater than 95%. Grading is not required because regardless of growth pattern (follicular vs diffuse), presence or absence of BCL-2 expression and/or t(14;18), multifocal lesions, or several centroblasts, there is no change in prognosis. Of note, PCFCL that presents on the legs has been shown to be more aggressive and portends a worse prognosis.[6][9]

Complications

If untreated, lesions of PCFCL will slowly increase over the years, but dissemination will only occur in 10% of cases. The generally indolent character of the disease has led to more low-morbidity modalities like radiotherapy. Surgical excision can sometimes lead to problems with cosmesis depending on the size, especially since PCFCL tends to occur on the head. Following therapy, patients are followed at regular intervals to monitor for relapse or treatment-related complications. Cutaneous relapses occur in approximately 30% of cases.[6][12]

Deterrence and Patient Education

PCFCL is a rare disease with a good prognosis, but it can often be confused with other types of lymphoma involving the skin, which may worsen the prognosis. Although lesions typically progress slowly over time, a full clinical evaluation is essential so a systemic or more aggressive process, such as PCDLBCL-LT, can be ruled out. Untreated lesions can be locally aggressive in some cases, and lesions on the legs have been noted to behave more aggressively (than head, neck, or trunk).

Pearls and Other Issues

The following information on primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is important pearls:

- PCFCL is the most common primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma.

- Lesions occur on the head, neck, or trunk in middle-aged to older males.

- Lesions on the legs have been shown to act more aggressively.

- Unlike systemic Follicular Lymphoma, it shows negative or weak BCL2 expression by immunohistochemistry and is negative for BCL-2 rearrangements by fluorescence in situ hybridization.

- PCFCL lymphoma is not graded.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The successful treatment of PCFCL relies heavily on a team-oriented, patient-centered approach. Diagnosis of PCFCL depends on clinical and histopathologic correlation. The treatment approach will be formulated based on the extent of the disease and proper identification. As some cases of PCFCL can act more aggressively than others, healthcare professionals need to provide a timely diagnosis.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, Cerroni L, Berti E, Swerdlow SH, Ralfkiaer E, Chimenti S, Diaz-Perez JL, Duncan LM, Grange F, Harris NL, Kempf W, Kerl H, Kurrer M, Knobler R, Pimpinelli N, Sander C, Santucci M, Sterry W, Vermeer MH, Wechsler J, Whittaker S, Meijer CJ. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005 May 15:105(10):3768-85 [PubMed PMID: 15692063]

Skala SL, Hristov B, Hristov AC. Primary Cutaneous Follicle Center Lymphoma. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2018 Nov:142(11):1313-1321. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2018-0215-RA. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30407851]

Willemze R, Cerroni L, Kempf W, Berti E, Facchetti F, Swerdlow SH, Jaffe ES. The 2018 update of the WHO-EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2019 Apr 18:133(16):1703-1714. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-11-881268. Epub 2019 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 30635287]

Bradford PT, Devesa SS, Anderson WF, Toro JR. Cutaneous lymphoma incidence patterns in the United States: a population-based study of 3884 cases. Blood. 2009 May 21:113(21):5064-73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184168. Epub 2009 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 19279331]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSwerdlow SH, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Willemze R, Kinney MC. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: report of the 2011 Society for Hematopathology/European Association for Haematopathology workshop. American journal of clinical pathology. 2013 Apr:139(4):515-35. doi: 10.1309/AJCPNLC9NC9WTQYY. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23525619]

Zinzani PL, Quaglino P, Pimpinelli N, Berti E, Baliva G, Rupoli S, Martelli M, Alaibac M, Borroni G, Chimenti S, Alterini R, Alinari L, Fierro MT, Cappello N, Pileri A, Soligo D, Paulli M, Pileri S, Santucci M, Bernengo MG, Italian Study Group for Cutaneous Lymphomas. Prognostic factors in primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: the Italian Study Group for Cutaneous Lymphomas. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006 Mar 20:24(9):1376-82 [PubMed PMID: 16492713]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCerroni L, Kerl H. Primary cutaneous follicle center cell lymphoma. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2001 Sep-Oct:42(5):891-900 [PubMed PMID: 11697644]

Bekkenk MW, Vermeer MH, Geerts ML, Noordijk EM, Heule F, van Voorst Vader PC, van Vloten WA, Meijer CJ, Willemze R. Treatment of multifocal primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: a clinical follow-up study of 29 patients. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1999 Aug:17(8):2471-8 [PubMed PMID: 10561311]

Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, Moskowitz A, Querfeld C, Myskowski PL. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. Clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2013 Sep:69(3):329.e1-13; quiz 341-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23957984]

Cerroni L, Arzberger E, Pütz B, Höfler G, Metze D, Sander CA, Rose C, Wolf P, Rütten A, McNiff JM, Kerl H. Primary cutaneous follicle center cell lymphoma with follicular growth pattern. Blood. 2000 Jun 15:95(12):3922-8 [PubMed PMID: 10845929]

Szablewski V, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Baia M, Delfau-Larue MH, Copie-Bergman C, Ortonne N. Primary Cutaneous Follicle Center Lymphomas Expressing BCL2 Protein Frequently Harbor BCL2 Gene Break and May Present 1p36 Deletion: A Study of 20 Cases. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2016 Jan:40(1):127-36. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000567. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26658664]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSenff NJ, Noordijk EM, Kim YH, Bagot M, Berti E, Cerroni L, Dummer R, Duvic M, Hoppe RT, Pimpinelli N, Rosen ST, Vermeer MH, Whittaker S, Willemze R, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma consensus recommendations for the management of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2008 Sep 1:112(5):1600-9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-152850. Epub 2008 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 18567836]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGoyal A, LeBlanc RE, Carter JB. Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America. 2019 Feb:33(1):149-161. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2018.08.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30497672]

Specht L, Dabaja B, Illidge T, Wilson LD, Hoppe RT, International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group. Modern radiation therapy for primary cutaneous lymphomas: field and dose guidelines from the International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2015 May 1:92(1):32-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.01.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25863751]