Introduction

Hepatic cysts (HCs) have been a common reason for consultation by gastroenterologists and hepatologists. HCs are defined as small abnormal fluid-filled lesions that develop within the liver tissue and usually arise from within hepatocytes, biliary cell epithelium, mesenchymal tissue, or metastases from extrahepatic organs. They may contain fluid or solid components. Liver cysts are mostly detected incidentally on imaging studies and tend to have a benign course. Small fractions are symptomatic and seldom associated with a significant life-threatening condition. HCs were discovered surgically before the use of diagnostic imaging. Simple cysts are the most common type. The prevalence of HCs is as high as 15-18% in the United States and 5 to 10% worldwide.[1]

Most of the cases can be managed expectantly and do not require interventions. However, in a few cases, the cysts will be large enough to cause symptoms and require medical or surgical interventions.

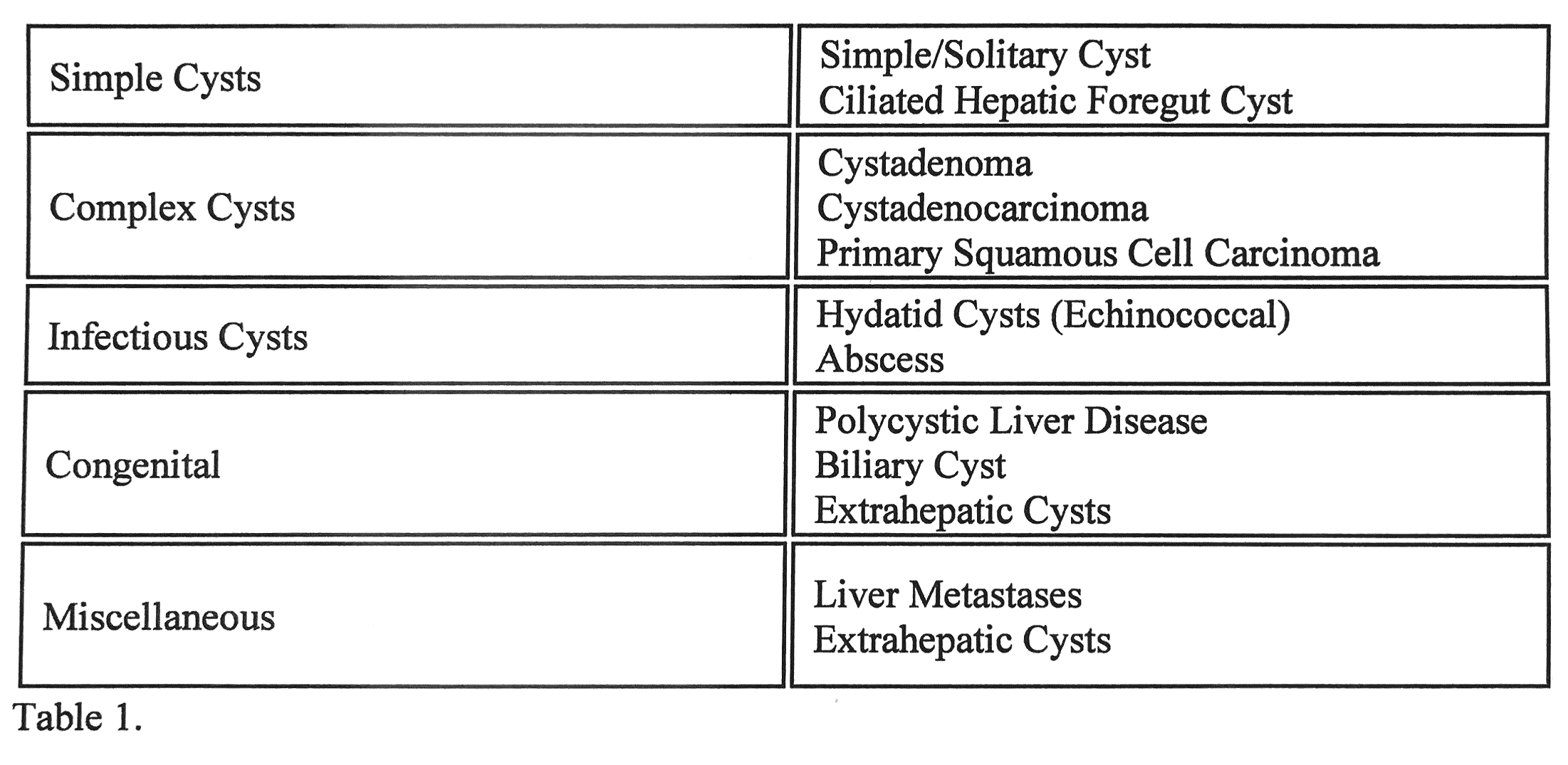

The differential diagnosis for liver cystic diseases is broad and includes infectious, inflammatory, neoplastic, congenital, and traumatic etiologies. In this review, we discuss the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, manifestation, and treatment modalities for different common primary hepatic cystic lesions rather than focusing on diagnosing and managing metastatic lesions, Infectious cysts, and Hepatocellular carcinoma.[2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

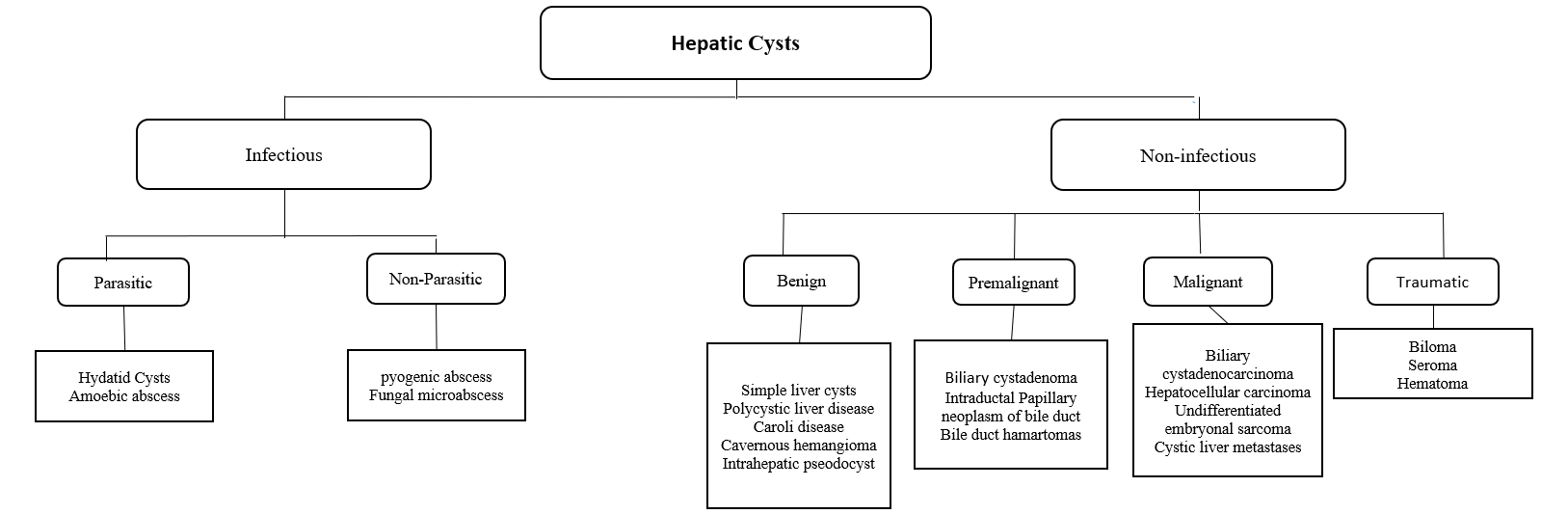

HCs can be classified into Infectious and Non-infectious. The first includes Benign, Neoplastic, and Traumatic. The latter is divided into Parasitic (Echinococcus and hydatid cyst) and Non-parasitic (pyogenic and fungal abscess).

Simple Cyst

It's the most common form of hepatic cysts. The underlying etiology of pathogenesis is not fully understood. Most simple cysts are congenital and usually arise from hyperplastic biliary ducts that are not connected to the biliary system.[1]

Polycystic Liver Disease (PCLD)

There are two mechanisms suggested for cysts development in PCLD. The first is thought to be due to retained abnormal bile ductules detached from the biliary tree and dilated progressively, forming cysts. Another suggested mechanism is an impairment of cilia within the biliary tree, leading to hyperproliferation of cholangiocytes and the generation of cysts. PCLD is congenital and is usually associated with Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD). Mutations in these patients have been identified in (PKD1 and PKD2 genes).

PCLD develops exclusively in patients with ADPKD. However, isolated PCLD was identified and reported as a separate illness in 1950 and had its genetic confirmation definition in 2003. Two genes are often found to be mutated (PRKCSH and SEC63). Despite these differences in genotype, patients with Isolated PCLD and ADPKD are similar phenotypically in liver involvement.[3][4]

In Autosomal recessive Polycystic kidney disease, patients tend to die shortly after birth due to pulmonary complications. However, those who survive tend to have liver fibrosis rather than a cyst.[5]

Gigot Criteria for PCLD relies on imaging findings and consists of 3 types:

- Type I: the presence of less than 10 large hepatic cysts and less than 20 cm in diameter maximum.

- Type II: diffuse involvement of liver parenchyma by multiple cysts with remaining large areas of patent liver parenchyma.

- Type III: diffuse involvement of liver parenchyma by different-sized liver cysts with slight areas of normal liver parenchyma.

Qian's classification relies on the number of cysts and used mainly for family members screening and consists of 5 grades:

- Grade 0: no cyst.

- Grade 1: 1-10 cysts.

- Grade 2: 11-20 cysts.

- Grade 3: > 20 cysts.

- Grade 4: > 20 cysts and symptomatic hepatomegaly. [6]

Neoplastic

Biliary cystadenoma (BCA) is a slow-growing neoplasm arising from the bile ducts. The pathogenesis is that these lesions are still unknown—suggestion of theory of superficial injury and reactive process. Alternatively, it is a congenital disease arising from ectopic remnants or aberrancy of embryonic bile ducts. Another theory is that these neoplasms are secondary to implantation, explaining the ovarian-like stroma, overexpression of estrogen and progesterone receptors. It has a heterogeneous mixture with septations occupied with either mucinous (95%) or serous (5%) components.[7][8]

Biliary cystadenocarcinoma (BCAC): differentiation between BCA and BCAC can be made through certain features, including demographic data, liver function tests, mass size, and presence of mural nodules. CA 19-9 are moderate predictors of BCAC. In conclusion, there are no definite reliable criteria to differentiate BCA from BCAC, and the definitive diagnosis is often made following surgery.[9]

Epidemiology

HCs on Ultrasound series have reported a 3 to 5% prevalence in the general population, whereas CT scan series have reported the prevalence in the range of 15% to 18%.

Simple cysts consider to be the most common pathology of the liver, with a prevalence of 2.5% to 5% of the general population and have a minimum female predilection (about 4 to 1) usually diagnosed after the age of 40. These cysts increase frequently with age and are sometimes multiple.[10]

Isolated PCLD has a prevalence of 1 to 10 cases per 1000000 individuals in the general population, while ADPKD ranged from 1 in 400 to 1 in 1000. ADPKD represents roughly 80 to 90% of all patients with PCLD. Due to the autosomal dominant inheritance pattern of Isolated PLCD, males and females should be at equal risk. However, findings show that the female to male ratio (about 6 to 1); is thought to be due to higher levels of estrogen in females compared to males. The prevalence of liver cysts in patients with ADPLD is found to be about 60%.[6]

The risk factors for the development and progression of severe PCLD are age, female sex, use of exogenous estrogens, multiple pregnancies, and the degree of renal involvement in case of coexisting ADPKD.[3]

Both BCAs and BCACs are rare and comprise only a small percentage of worldwide HCs disease patients. Although rare, Biliary cystadenomas are reported to constitute up to 1% to 5% of HCs and considered the most common primary hepatic cystic neoplasm. BCAs are seen predominantly in middle-aged women (9 to 1) to males with ages ranging between 40 to 50 years old. They are slow-growing lesions and have been reported to reach sizes up to 30 cm. The reported rate of malignant transformation to BCAC can be as high as 30%. They are commonly found in the posterior segment of the right liver lobe, likely because the right lobe contains the most hepatic tissue.[8]

History and Physical

It is imperative to complete a thorough evaluation of the clinical circumstances such as the patient’s age, gender, a complete history, and physical examination, use of a hormonal form of contraceptive, history of chronic liver disease, and travel history may provide vital clues to the etiology.

HCs generally cause no symptoms. however, A small fraction of patients manifests with dull right upper quadrant abdominal pain, early postprandial satiety, nausea, vomiting, and Shortness of breath, which arise from a mass effect. Infrequently, a cyst is large enough to produce a palpable abdominal mass and is associated with serious morbidity and mortality.

Furthermore, bile duct obstruction presented as jaundice and itching, rupture of the cyst could cause bacterial peritonitis or presentation similar to hepatic abscesses in the form of fever, abdominal pain, and leukocytosis. It also could cause acute torsion of the cyst presented as acute abdomen.[11]

The detection of multiple liver cysts requires extensive family history taking regarding the occurrence of ADPKD or PCLD. Clinically, patients could present as hepatomegaly on physical examination, and patients rarely progress to hepatic fibrosis, portal hypertension, and liver failure. Infrequently, the liver cysts will impinge the vascular structures of the liver, leading to portal hypertension and upper GI bleeding in terms of Esophageal Varices. Patients with liver cysts can also experience impingement on the Portal veins causing a presentation similar to 'Budd-Chiari syndrome, which blocks the venous drainage from the liver.[12][13]

Recurrent right exudative pleural effusion has been reported in a patient with PCLD.[14]

In ADPKD, patients present with kidney cysts with an extrarenal manifestation include Cerebral aneurysms, pancreatic cysts, Cardiac valve disease, Colonic diverticula, Abdominal wall, inguinal hernia, and seminal vesicle cyst.

BCA and BCAC generally have a similar clinical presentation. BCAC invades the adjacent biliary tree, while BCA is a slow-growing tumor and causes late biliary compression.

Evaluation

Laboratory Testing

Labs are typically nondiagnostic and are predominantly normal. A minority of patients may be mild elevations in liver enzymes, most commonly in alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transferase. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA 19-9 may be elevated. CA 19-9 is expressed in the inner epithelial lining of a simple cyst; it might be beneficial as a diagnostic or follow-up biomarker.

In the context of PCLD, more significant changes in Liver function test results are found, but liver failure is uncommon. Renal function test results, including blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels, are often abnormal and should be performed on initial evaluation and followed up over the course of the disease.

Higher enzyme levels in BCAC over BCA occur due to the invasion of the adjacent biliary tree.

Imaging Modalities

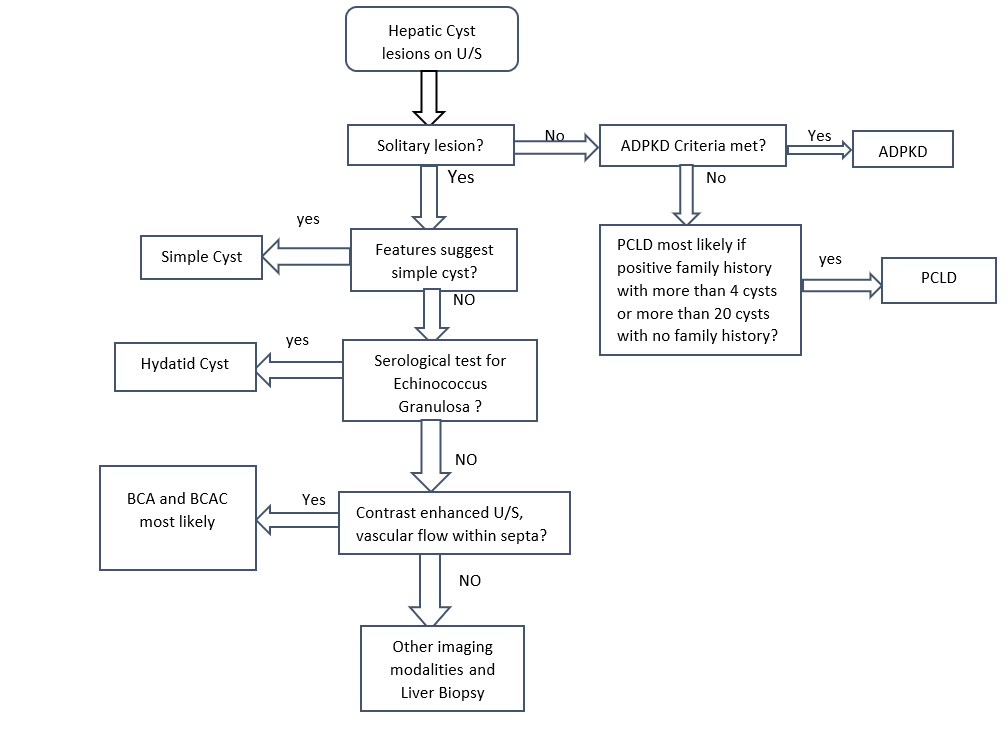

HCs were discovered incidentally while performing surgery. Physicians have several options for imaging the liver in patients with HCs. Abdominal Ultrasonography is readily available, noninvasive, highly sensitive, and lacks harmful radiation exposure. CT scan is sensitive and is easier for most clinicians to interpret, particularly for treatment planning. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), hepatic angiography, and nuclear medicine scanning have a limited part in managing hepatic cysts.

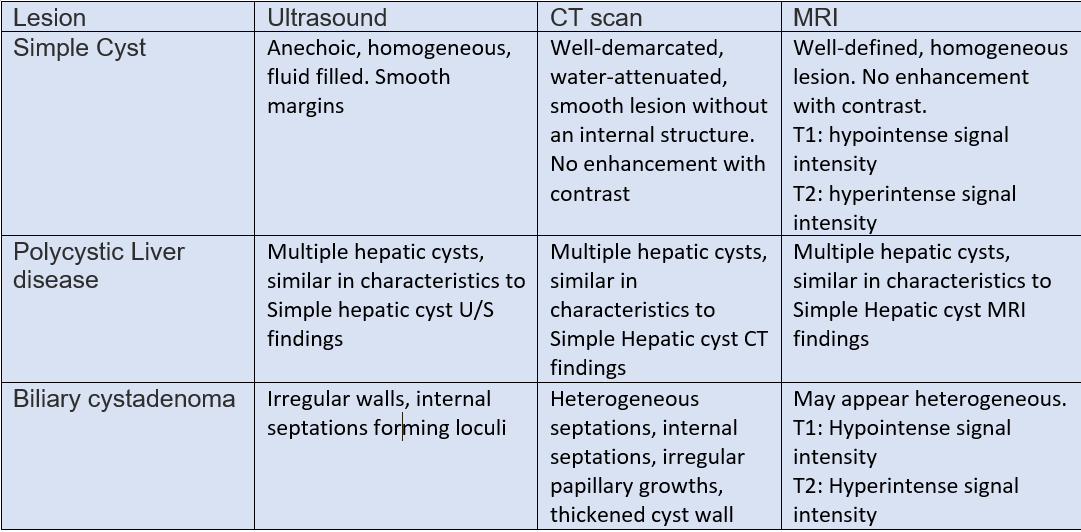

The Ultrasound can generally differentiate a simple cyst from a complicated one. Different characteristics to differentiate between these lesions. In simple hepatic cysts, it appears anechoic, homogeneous, no septate, thin, with smooth margins, and there is a posterior acoustic enhancement. However, a hemorrhagic simple cyst can lead to confusion in the U/S findings between a simple cyst and a mucinous cystic neoplasm. On CT scan shows sharply defined homogeneous hypodense lesions. The well-demarcated homogenous lesion does not enhance following the administration of intravenous contrast.

Radiologically, simple cyst and PCLD carries similar findings. There are no specific radiological criteria to differentiate liver cysts in the case of ADPKD and isolated PCLD. The diagnosis is usually made through the presence of >20 liver cysts as measured by an imaging modality. An ultrasound to identify cysts in the liver and kidney is recommended as the initial test. ADPKD should be tested for and excluded before making the diagnosis of isolated PCLD; unfortunately, up to one-third of patients with isolated PCLD can have a few kidney cysts, making it difficult to distinguish between the two. The diagnostic criteria for ADPKD1 for high risks patients with a family history are through the presence of at least two cysts in 1 kidney or 1 cyst in each kidney in a patient younger than 30 years, at least two cysts in each kidney in a patient between 30 and 59 years. and at least 4 cysts in each kidney for a patient at 60 years or older.[3]

Patients with ADPKD with a reasonably estimated life expectancy should undergo periodic evaluation every 3 to 5 years with MRA or CTA for cerebral aneurysm. In contrast, screening for intracranial aneurysms and extrahepatic manifestation is not needed for patients with Isolated PCLD.[15]

Cysts with features of neoplastic or infectious causes, including internal septations, fenestrations, edge calcifications, irregular walls, and associated daughter cysts within ultrasound, should be evaluated with CT or MRI for features of BCA or hydatid cysts. Neoplastic cysts are slow-growing, single, multilocular filled with a clear mucinous or serous fluid. These lesions show capsular and septal enhancement following contrast administration. The presence of internal fragments, bile duct expansion, and enhancing mural nodularity raise concerns for BCACs. MRI is preferred for pre-surgical evaluation to assess biliary communication and evaluate cystic content materials.[16][17]

Histology and Needle Aspiration

It is seldom needed for establishing the diagnosis since they have a typical sonographic appearance. In simple cysts, the aspirated fluid is typically sterile. It varies from clear straw color to brown. PCLD cysts are microscopically similar to simple hepatic cysts.

High levels of carcinoembryonic antigen in the cyst fluid have been reported in neoplastic cysts with associated invasive carcinoma, but the diagnostic accuracy of this finding has not been established. Fine-needle aspiration of cyst fluid is no longer the first recommendation for neoplastic patients due to the increased risk of tumor seeding and the development of peritoneal carcinosis.

BCAs have numerous septa on the gross specimen, surrounded by a thick fibrous capsule that might include calcifications. Microscopically, BCAs have three characteristic layers, including a mucin-producing, with a stratified or pseudo-stratified non-ciliated cuboidal or columnar epithelial layer; a second layer of cellular stroma; and an innermost layer of thick collagenous connective tissue. They consist of a bloody or chocolate-colored material.

Biopsy and histological findings remain the gold standard for BCA diagnosis and differentiation from BCAC. However, it is usually done following surgical resection.[18]

Genetic Testing

PCLD has an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, and it has a recurrence risk is 50% within the next generation. However, genetic testing for patients with ADPKD and PCLD is available but is not usually performed regularly as it does not interfere with the management. However, patients with a family history of ADPKD or PCLD could consider molecular genetic testing. Screening mutations of the genes causing ADPKD (PKD1 and PKD2) or Isolated PCLD (PRKCSH and SEC63) confirm the clinical diagnosis. The prevalence of the disease is too low, so no recommendations for screening for the general population.[19]

Treatment / Management

Simple Cyst

Asymptomatic simple cysts do not require intervention other than regular follow up with imaging studies and expectant management. Follow-up with Ultrasounds could be done at 3 to 12 months intervals, and if the cysts are stable, there is no need for further follow-up.

simple cysts have even been reported to resolve spontaneously on the follow-up period without a needed intervention.[20]

Symptomatic patients or cysts that are increasing in size should raise concern that the lesion could be neoplastic. Several therapeutic approaches including needle aspiration with or without injection of sclerosing agents such as (tetracycline, ethanol, or ethanolamine), internal drainage with wide unroofing, and varying degrees of liver resection. The laparoscopic approach is the current standard of care, but studies have shown recurrence rates varying from 4% to 41% on follow-up after laparoscopic surgery.[1] With the help of a sclerosing agent, the recurrence rate is decreased significantly.[21]

Polycystic Liver Disease

Management is focused on decompressing the liver volume. There are no recent guidelines to manage PCLD alone. However, there are medical and/or surgical approaches that include:[22](B3)

A. Medical Therapy

- Somatostatin receptor antagonist: Octreotide is a somatostatin receptor antagonist that has a positive effect on patients with PCLD.

- mTOR inhibitor: mTOR is found to be inappropriately activated in patients with PCLD and thought to be responsible for its proliferation. Sirolimus shows to halt the proliferation and synthesis response of unregulated polycystic cells.

- Estrogen receptor antagonists: The current belief is that estrogen plays a role in cyst growth, and as a result, the disease tends to affect women more than men. However, there have been no clinical trials performed besides anecdotal reports.[23]

- Vasopressin-2-receptor antagonists: studies show that activation of vasopressin receptor leads to increased cAMP production, which leads to the proliferation of cysts. Studies have shown that using tolvaptan blocks. This receptor can lead to a decrease in the rate of cyst development and growth. However, these studies did not analyze tolvaptan’s effect on liver cysts. Even so, there have been several case studies that suggest that tolvaptan may reduce liver volume and improve patients' symptoms.

B. Surgical Therapy

- Percutaneous Cyst Aspiration followed by Sclerotherapy: can be diagnostic and/or therapeutic. It is done through aspiration of a cyst under sonographic guidance followed by injection of a sclerosing agent that destructs the lining epithelial, preventing fluid accumulation. It is mainly indicated for patients with a large symptomatic liver cyst (>5 cm).[24]

- Laparoscopic Cyst Fenestration: It involves aspiration and deroofing of the cyst in a single procedure. The main advantage of the procedure that multiple cysts can be treated at the same time. Usually done when there are a few large dominant cysts in the anterior segments of the right lobe or the left lateral segments of the hepatic lobes.

- Segmental Hepatic Resection: it is considered in patients with massive liver cysts but has enough remnant liver parenchymal tissue. The procedure is usually only for patients with massive hepatomegaly with severe symptoms, and when liver transplantation is unwarranted.[25]

- Transplantation: Patients with PCLD typically have low MELD score due to normal liver function tests. However, it is rarely indicated in the case of impaired liver function and where resection is not considered to be a feasible option due to diffuse cystic lesions.[26][27] (B3)

Neoplastic Cysts

BCA is considered a premalignant lesion. The tumors grew to a large size and required surgical intervention in most reports. Although imaging findings may be suggestive, they often overlapped and nonspecific. There are no published guidelines on appropriate therapy of BCAs and BCACs due to the limited number of reported cases. Fluid aspiration routinely to decompress the cystic lesion is not recommended because of limited sensitivity and the risk of malignant dissemination.[1]

Complete radical surgical resection with a wide(>2cm) surgical margin is the management of choice given the risk of malignant transformation and recurrence. Enucleation of BCAs is appropriate management only in those cases where complete surgical resection is not possible. BCAC has a good prognosis compared to other hepatic malignancies, as it exhibits less aggressive clinical behavior with slow growth and less frequent metastases.

Serum CA 19-9 can be monitored at regularly spaced intervals has been suggested for post-surgical tumor resolution.[28][29]

Differential Diagnosis

Non-infectious

Benign

- Biliary Hamartomas: also known as von Meyenburg complexes are rare benign congenital lesions consisting of small-sized dilated bile ducts surrounded by fibrous tissue. Patients are usually asymptomatic. Ultrasound findings show hypoechoic, hyperechoic, or mixed heterogenic echoic structures. They require no treatment. Unlike Caroli disease, they do not communicate with the biliary system.[30]

- Caroli Disease: is a rare benign autosomal recessive condition that manifests with multifocal cystic dilatation of segmental intrahepatic bile ducts. Patients present with frequent or recurrent bouts of cholangitis or those with portal hypertension and biliary cirrhosis. Ultrasound shows saccular dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts, intraductal bridging, echogenic septa traversing the dilated bile duct lumen, and small portal venous branches partially or fully surrounded by dilated bile ducts. If the disease is localized, segmentectomy, or lobectomy may be done. In diffuse disease management, usually, with conservative measures, liver transplantation may be an option.[31]

- An Intrahepatic Pseudocyst: is a rare condition that may occur in the setting of alcoholic pancreatitis. It may require prompt percutaneous or endoscopic drainage or surgical resection if it is large or symptomatic to prevent complications.[32]

- Cavernous Hemangioma: are benign tumors of the liver consisting of clusters of blood-filled cavities lined by endothelial cells, supplied by branches of the hepatic artery. On ultrasound, it appears as a hyperechoic homogenous nodule with well-defined margins. it is mostly asymptomatic and requires regular imaging studies.[33]

Neoplastic

- Cystic Liver Metastases: These are the most important concerns to be excluded when multiple cystic lesions are found within the liver. Clinical history of a primary mass and multiplicity of the lesions are classic features of hepatic metastases. The most common primary sources are colon, kidney, prostate, testis, ovary, lung, sarcomas, and neuroendocrine tumors. Colon cancer comprises 50% of cases of metastatic cancer. The radiological findings will vary depending on the primary cause. On Ultrasound, it usually shows hypoechoic, thick septations and may demonstrate increased vascularity on color doppler imaging.[28]

- Undifferentiated Embryonal Sarcoma: is a highly malignant hepatic neoplasm (typical presents at age 6-10 years), rarely seen in late childhood and early adulthood. The pediatric population is considered the third most common liver tumor in pediatrics, accounting for approximately 10%. On ultrasound, it appears as a large mass with mixed solid and cystic components. Hence some authors suggest that UES arises from mesenchymal tissue. Management includes surgical resection and chemotherapy. it is known to have a poor prognosis.[34]

- Intraductal Papillary Neoplasms of the Bile Duct: are rare tumors due to papillary growth within the bile duct lumen. It is usually associated with mucin secretion, and cystic biliary dilatation is characteristic. It does not consider to be premalignant lesions. However, Patients usually present with bouts of recurrent cholangitis and obstructive jaundice and should be considered for resection.[35]

Traumatic

- Biloma: is an intra-or extra-hepatic bile collection outside the biliary tree. It usually occurs due to iatrogenic injury, following cholecystectomy, or by a blunt abdominal injury.[36]

- Hematoma: mostly followed a blunt abdominal trauma. It considered being the second most frequent abdominal organ injured during blunt trauma after the spleen.[37]

Infectious

- Hydatid Cyst: Patients are most often asymptomatic, but pain may develop as the cyst grows. Patients generally have a palpable mass in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. The most serious complication of hydatid cysts is rupture. They may rupture into the adjacent biliary tree causing jaundice or cholangitis, through the diaphragm into the chest, or into the peritoneal cavity causing anaphylactic shock. Usually diagnosed incidentally. Can cause compression of surrounding tissue. Imaging shows eggshell calcification of liver cyst, which is highly suggestive of hydatid cyst. Treatment usually through surgical resection under cover of albendazole. In a few cases, aspiration may be done, but there is a risk of anaphylactic shock due to cyst content spillage.[38]

- Hepatic Abscesses: patients usually present with abdominal pain, extreme fever, and leukocytosis. In amoebiasis, patients usually describe a history of diarrhea, weight loss, and travel history to an endemic region. Metronidazole is the drug of choice with more than 90% cure with oral metronidazole. Paromomycin is used for the eradication of intestinal amoebiasis. While Pyogenic abscesses often present with cholangitis, abdominal infections, following surgery, or sepsis. Rarely, abscesses may rupture present as peritonitis. It is more common in the elderly with other comorbid conditions like diabetes, hepatobiliary disease, or following peritonitis. a liver abscess will appear on imaging and treated with IV antibiotics and drainage.[39]

Prognosis

The simple cyst usually has a good prognosis and follow it up with imaging studies. After surgical interventions, it usually doesn't require follow-up unless the patient becomes symptomatic, and there is a high risk of recurrence rates.

Isolated PCLD has a benign prognosis compared with ADPLD and is mainly asymptomatic. The primary aim of PCLD treatment focused on reducing liver volume. However, surgical interventions carry a high risk of significant morbidity. Nevertheless, the benefits should be weighed carefully against their complications. A Progression to the end-stage liver is expected in the context of extremely increased liver mass.

Liver failure is seen incidentally, usually in a late stage of the disease. Liver volume is considered a prognostic tool as it affects both symptom burden and patients' quality of life. In liver diseases, the MELD score used to assess three-month prognosis in patients with liver failure is a leading tool to select patients for liver transplantation. As the function of the liver in patients with PCLD remains intact, this score will not increase.[27]

PCLD patients who are carriers of mutations in PRKCSH or SEC63 showed a more severe disease course than patients without a known mutation. Also, patients with mutations in PKD2 have more favorable renal prognosis than patients with mutations in PKD1.

For BCA and BCAC, there are limited prognostic factors following resection of BCA and BCAC due to the paucity of the disease. However, the overall prognosis is considered better than other malignant tumors of the liver. Some studies have found that favorable outcomes occur in patients who perform total resection resulting in only a 5% to 10% recurrence rate.[40]

Complications

Larger cysts are more likely to cause significant symptoms and cause complications.

Reported complications include hemorrhage, rupture into the peritoneal cavity following a traumatic event, bile duct torsion, secondary infection, compression of the biliary tree, Malignant transformation in case of cystadenoma, and anaphylactic shock due to a hydatid cyst—several other rare complications such as Budd-Chiari syndrome secondary to a rapidly enlarging cyst obstructing the hepatic vein. Also, a case report described an inferior vena cava thrombus caused by external pressure from a simple hepatic cyst had been reported.[41]

Liver failure is a rare manifestation in patients with isolated PLCD. In patients with co-existing ADPKD patients, extrarenal manifestations include Cerebral aneurysms, pancreatic cysts, Cardiac valve disease, Colonic diverticula, Abdominal wall, inguinal hernia, and seminal vesicle cyst might exist and should be evaluated.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Malignancy is often the concern with liver masses. However, most liver masses diagnosed as incidentalomas, benign, and require only monitoring and patient reassurance. It is important to educate patients about the benign nature of simple hepatic cysts. However, patients should be educated about the possible bleedings within hepatic cysts, especially while using anticoagulation drugs.[42]

In PCLD, the patients should be advised to avoid using an exogenous source of estrogen and use alternative contraceptive strategies. Due to its autosomal dominant inheritance, family members may need to perform regular screening and genetic evaluations.

General recommendations for all individuals affected by and at a high-risk of ADPKD include a healthy lifestyle and diet, limit dairy protein, maintenance of optimal weight, restrict salt intake, regular aerobic exercise, avoid caffeine, smoke cessation, and limiting the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents and ACIs and ARBs. Overweight and obesity are associated with deterioration in their GFR and increased total kidney volume in early-stage ADPKD.[43][3]

In BCA, Patients should receive education about the need to do a complete resection, as they are at high risk for malignant transformations into BCAC.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of hepatic cysts often require integrating multiple aspects of care, involving various sub-specialties: primary care physicians, interventional radiology, oncologist, hepatology, nephrology, infectious diseases, surgery, a specially trained nurse, and pharmacists. It is important for the involved physicians to coordinate patient care to provide the best healthcare possible, improve their outcomes, and achieve optimal patient results.[44]

HCs encounters for a wide range of disorder. Physicians must have a high index of suspicion for rare diseases to provide as accurate a diagnosis as possible.

Enhancing patient outcomes starts with the clinician's awareness of BCA and the associated risk of developing BCAC. A thorough history and imaging are essential to differentiate this entity from other benign hepatic cysts due to different management options. The clinicians need to follow the patient with sequential imaging to ensure that malignant transformation does not occur. Following surgery, there is a risk of recurrence of BCAC; thus, patients require monitoring for any symptom development and imaging findings.

There is a paucity of randomized controlled trials and research other than anecdotal reports comparing treatment methods for simple hepatic cysts.[1]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

CT scan of the abdomen shows Autosomal Dominant Polycystic disease

Steven Fruitsmaak, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

References

Marrero JA, Ahn J, Rajender Reddy K, Americal College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: the diagnosis and management of focal liver lesions. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2014 Sep:109(9):1328-47; quiz 1348. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.213. Epub 2014 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 25135008]

Vachha B, Sun MR, Siewert B, Eisenberg RL. Cystic lesions of the liver. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2011 Apr:196(4):W355-66. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5292. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21427297]

Cornec-Le Gall E, Alam A, Perrone RD. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet (London, England). 2019 Mar 2:393(10174):919-935. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32782-X. Epub 2019 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 30819518]

Lee-Law PY, van de Laarschot LFM, Banales JM, Drenth JPH. Genetics of polycystic liver diseases. Current opinion in gastroenterology. 2019 Mar:35(2):65-72. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000514. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30652979]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKothadia JP, Kreitman K, Shah JM. Polycystic Liver Disease. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31751072]

Abu-Wasel B, Walsh C, Keough V, Molinari M. Pathophysiology, epidemiology, classification and treatment options for polycystic liver diseases. World journal of gastroenterology. 2013 Sep 21:19(35):5775-86. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i35.5775. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24124322]

Kazama S, Hiramatsu T, Kuriyama S, Kuriki K, Kobayashi R, Takabayashi N, Furukawa K, Kosukegawa M, Nakajima H, Hara K. Giant intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma in a male: a case report, immunohistopathological analysis, and review of the literature. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2005 Jul:50(7):1384-9 [PubMed PMID: 16047491]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAverbukh LD, Wu DC, Cho WC, Wu GY. Biliary Mucinous Cystadenoma: A Review of the Literature. Journal of clinical and translational hepatology. 2019 Jun 28:7(2):149-153. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2019.00017. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31293915]

Dixon E, Sutherland FR, Mitchell P, McKinnon G, Nayak V. Cystadenomas of the liver: a spectrum of disease. Canadian journal of surgery. Journal canadien de chirurgie. 2001 Oct:44(5):371-6 [PubMed PMID: 11603751]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCarrim ZI, Murchison JT. The prevalence of simple renal and hepatic cysts detected by spiral computed tomography. Clinical radiology. 2003 Aug:58(8):626-9 [PubMed PMID: 12887956]

Martin WP, Vaughan LE, Yoshida K, Takahashi N, Edwards ME, Metzger A, Senum SR, Masyuk TV, LaRusso NF, Griffin MD, El-Zoghby Z, Harris PC, Kremers WK, Nagorney DM, Kamath PS, Torres VE, Hogan MC. Bacterial Cholangitis in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney and Liver Disease. Mayo Clinic proceedings. Innovations, quality & outcomes. 2019 Jun:3(2):149-159. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2019.03.004. Epub 2019 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 31193902]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLong J, Vaughan-Williams H, Moorhouse J, Sethi H, Kumar N. Acute Budd-Chiari syndrome due to a simple liver cyst. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2014 Jan:96(1):109E-111E. doi: 10.1308/003588414X13824511649698. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24417858]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKhan MS, Khan Z, Javaid T, Akhtar J, Moustafa A, Lal A, Tiwari A, Taleb M. Isolated Polycystic Liver Disease: An Unusual Cause of Recurrent Variceal Bleed. Case reports in gastrointestinal medicine. 2018:2018():2902709. doi: 10.1155/2018/2902709. Epub 2018 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 29971171]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWoolnough K, Palejwala A, Bramall S. Polycystic liver disease presenting with an exudative pleural effusion: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2012 Apr 13:6():107. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-6-107. Epub 2012 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 22502729]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePirson Y, Chauveau D, Torres V. Management of cerebral aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2002 Jan:13(1):269-276. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V131269. Epub [PubMed PMID: 11752048]

Labib PL, Aroori S, Bowles M, Stell D, Briggs C. Differentiating Simple Hepatic Cysts from Mucinous Cystic Neoplasms: Radiological Features, Cyst Fluid Tumour Marker Analysis and Multidisciplinary Team Outcomes. Digestive surgery. 2017:34(1):36-42 [PubMed PMID: 27384180]

Aksoy S, Erdil I, Hocaoglu E, Inci E, Adas GT, Kemik O, Turkay R. The Role of Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Differential Diagnosis of Simple and Hydatid Cysts of the Liver. Nigerian journal of clinical practice. 2018 Feb:21(2):212-216. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_296_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29465057]

Choi HK, Lee JK, Lee KH, Lee KT, Rhee JC, Kim KH, Jang KT, Kim SH, Park Y. Differential diagnosis for intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and hepatic simple cyst: significance of cystic fluid analysis and radiologic findings. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2010 Apr:44(4):289-93. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181b5c789. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19770676]

Cornec-Le Gall E, Torres VE, Harris PC. Genetic Complexity of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney and Liver Diseases. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2018 Jan:29(1):13-23. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017050483. Epub 2017 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 29038287]

Lee DM, Kwon OS, Choi YI, Shin SK, Jang SJ, Seo H, Lee JJ, Choi DJ, Kim YS, Kim JH. [Spontaneously Resolving of Huge Simple Hepatic Cyst]. The Korean journal of gastroenterology = Taehan Sohwagi Hakhoe chi. 2018 Aug 25:72(2):86-89. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2018.72.2.86. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30145861]

Vardakostas D, Damaskos C, Garmpis N, Antoniou EA, Kontzoglou K, Kouraklis G, Dimitroulis D. Minimally invasive management of hepatic cysts: indications and complications. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2018 Mar:22(5):1387-1396. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201803_14484. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29565498]

Drenth JP, Chrispijn M, Nagorney DM, Kamath PS, Torres VE. Medical and surgical treatment options for polycystic liver disease. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 2010 Dec:52(6):2223-30. doi: 10.1002/hep.24036. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21105111]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEverson GT, Helmke SM. Somatostatin, estrogen, and polycystic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2013 Aug:145(2):279-82. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.06.025. Epub 2013 Jun 24 [PubMed PMID: 23806538]

Cheng D, Amin P, Ha TV. Percutaneous sclerotherapy of cystic lesions. Seminars in interventional radiology. 2012 Dec:29(4):295-300. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1330063. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24293802]

Yang GS, Li QG, Lu JH, Yang N, Zhang HB, Zhou XP. Combined hepatic resection with fenestration for highly symptomatic polycystic liver disease: A report on seven patients. World journal of gastroenterology. 2004 Sep 1:10(17):2598-601 [PubMed PMID: 15300916]

van Aerts RMM, van de Laarschot LFM, Banales JM, Drenth JPH. Clinical management of polycystic liver disease. Journal of hepatology. 2018 Apr:68(4):827-837. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.11.024. Epub 2017 Nov 24 [PubMed PMID: 29175241]

Tang H, Ding F, Yao J, Xu C, Zhang J, Wang GS, Yi SH, Li H, Yang Y, Chen GH. [Liver transplantation for polycystic liver disease: 11 cases report and literature review]. Zhonghua yi xue za zhi. 2019 Mar 12:99(10):767-770. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2019.10.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30884632]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGroen KA. Primary and metastatic liver cancer. Seminars in oncology nursing. 1999 Feb:15(1):48-57 [PubMed PMID: 10074657]

Ratti F, Ferla F, Paganelli M, Cipriani F, Aldrighetti L, Ferla G. Biliary cystadenoma: short- and long-term outcome after radical hepatic resection. Updates in surgery. 2012 Mar:64(1):13-8. doi: 10.1007/s13304-011-0117-0. Epub 2011 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 22038379]

Lanser HC, Puckett Y. Biliary Duct Hamartoma. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491682]

Kyalwazi B, Kudaravalli P, John S. Caroli Disease. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020679]

Angsubhakorn N, Laub L, Keenan JC. ERCP-associated infected intrahepatic pancreatic pseudocyst. IDCases. 2019:15():e00507. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2019.e00507. Epub 2019 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 30847279]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBruguera M. [Cavernous hemangioma]. Gastroenterologia y hepatologia. 2006 Aug-Sep:29(7):428-30 [PubMed PMID: 16938260]

Putra J, Ornvold K. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver: a concise review. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2015 Feb:139(2):269-73. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0463-RS. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25611111]

Park HJ, Kim SY, Kim HJ, Lee SS, Hong GS, Byun JH, Hong SM, Lee MG. Intraductal Papillary Neoplasm of the Bile Duct: Clinical, Imaging, and Pathologic Features. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2018 Jul:211(1):67-75. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.19261. Epub 2018 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 29629808]

Watanabe H, Sawabu N. [Hepatic biloma]. Ryoikibetsu shokogun shirizu. 1995:(8):106-8 [PubMed PMID: 8581578]

Richie JP, Fonkalsrud EW. Subcapsular hematoma of the liver. Nonoperative management. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1972 Jun:104(6):781-4 [PubMed PMID: 5029409]

Fadel SA, Asmar K, Faraj W, Khalife M, Haddad M, El-Merhi F. Clinical review of liver hydatid disease and its unusual presentations in developing countries. Abdominal radiology (New York). 2019 Apr:44(4):1331-1339. doi: 10.1007/s00261-018-1794-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30306203]

Lardière-Deguelte S, Ragot E, Amroun K, Piardi T, Dokmak S, Bruno O, Appere F, Sibert A, Hoeffel C, Sommacale D, Kianmanesh R. Hepatic abscess: Diagnosis and management. Journal of visceral surgery. 2015 Sep:152(4):231-43. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2015.01.013. Epub 2015 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 25770745]

Xu M, Shi X, Wan T, Wang H, He L, Chen M, Liang Y, Dong J. [Clinicopathological characteristics and prognostic factors of intrahepatic biliary cystadenocarcinoma]. Nan fang yi ke da xue xue bao = Journal of Southern Medical University. 2015 Aug:35(8):1097-102 [PubMed PMID: 26277503]

Park J. Traumatic rupture of a non-parasitic simple hepatic cyst presenting as an acute surgical abdomen: Case report. International journal of surgery case reports. 2019:65():87-90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2019.10.051. Epub 2019 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 31698200]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTong KS, Hassan R, Gan J, Warsi A. Simple hepatic cyst rupture exacerbated by anticoagulation. BMJ case reports. 2019 Sep 16:12(9):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-230243. Epub 2019 Sep 16 [PubMed PMID: 31527205]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSuyama Y, Horie Y, Suou T, Hirayama C, Ishiguro M, Nishimura O, Koga S. Oral contraceptives and intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma having an increased level of estrogen receptor. Hepato-gastroenterology. 1988 Aug:35(4):171-4 [PubMed PMID: 3181863]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBakoyiannis A, Delis S, Triantopoulou C, Dervenis C. Rare cystic liver lesions: a diagnostic and managing challenge. World journal of gastroenterology. 2013 Nov 21:19(43):7603-19. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i43.7603. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24282350]