Introduction

Neutrophils are historically defined as "soldiers of our innate immune system." They are the first line of cells recruited at the site of infection and attack, ingest, and digest microorganisms by producing reactive oxygen species.[1] They also play a vital role in acute and chronic inflammatory settings and autoimmune disorders.[2] In adults, the approximate normal range of white blood cell (WBC) count is 4000 to 11,000 cells/microL, out of which 60% to 70% are mature neutrophils circulating in peripheral blood.[3]

An absolute neutrophil count (ANC), defined as the percent of neutrophils in the bloodstream and adults, typically ranges between 2500 to 7000 neutrophils/microL. An increase in the WBC count of more than 11,000 cells/microL is defined as leukocytosis. Neutrophilia is the most common type of leukocytosis. It is defined as an increase in the absolute neutrophil count of approximately more than 7700 neutrophils/microL (11,000 cells/microL x 70 percent), i.e., two standard deviations above the mean.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Causes of Neutrophilia are classified into the following categories:

- Factitious neutrophilia; neutrophilia due to various artifacts encountered during blood sample handling in laboratory settings

- Primary Neutrophilia; neutrophilia due to abnormal increased neutrophils production by bone marrow due to impaired neutrophil production regulation.

- Secondary Neutrophilia; reactive neutrophilia can respond to a wide variety of stimuli mentioned in detail below.

Factitious Neutrophilia

Factitious neutrophilia can be seen in the blood samples that are either inadequately anticoagulated with citrate or heparin or are EDTA- based anticoagulated, causing platelet clumping in an automated cell counter leading to falsely elevated neutrophil count. A repeat blood sample with adequate anticoagulation (with heparin or citrate) and an examination of the peripheral blood smear (showing platelet clumping) can help resolve this problem.[4][5] Another possibility in which neutrophil count can be falsely elevated is precipitated cryoglobulin particles in a blood sample. Cryoglobulin is a cold insoluble protein, and a repeat blood sample at body temperature should resolve this issue.[6]

Primary Neutrophilia

Chronic Idiopathic Leukocytosis: Given neutrophilia is defined as an ANC of at least two standard deviations above the mean, neutrophil counts can vary considerably among asymptomatic healthy individuals, and 2.5 percent of the population can be considered to have neutrophilia based on the definition mentioned above. Serial evaluations may be required in an average healthy individual with mild neutrophilia to rule out the absence of underlying pathology. Since neutrophil count regulation is also genetically controlled, evaluation of a sibling's or parent s blood count can be helpful in this situation.[7]

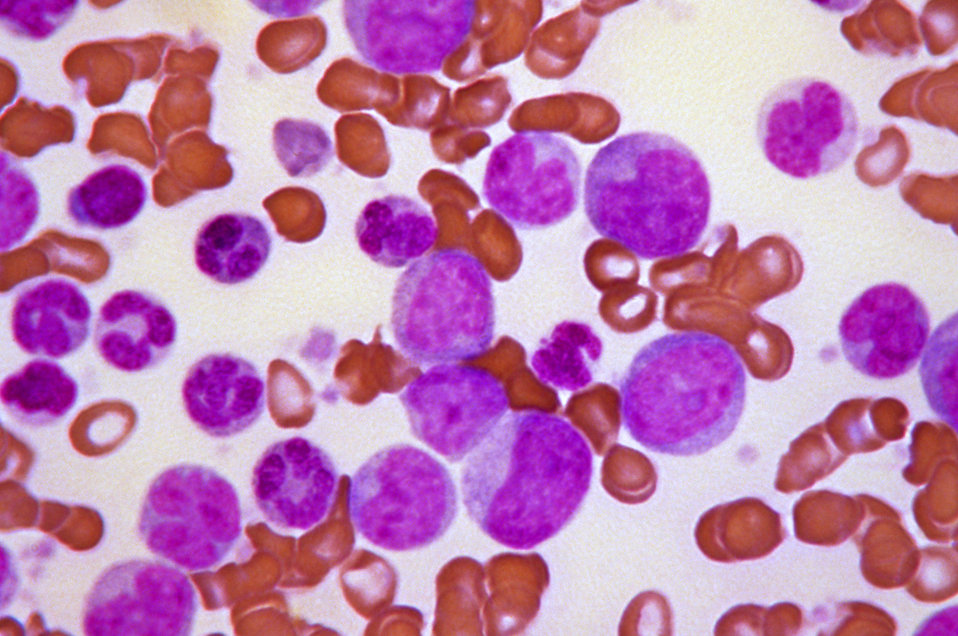

Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPN): MPNs are characterized by excess and autonomous production of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets, thus can be a cause of primary neutrophilia. MPNs associated with neutrophilia include Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), essential thrombocythemia (ET), polycythemia vera (PV), chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, chronic neutrophilic leukemia, Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML).[8][9]

Genetic/ Inherited neutrophilia: The subset of the population affected by this category is neonates and children, with some disorders being detected in adulthood. Leukocyte adhesion factor deficiency is a rare but life-threatening disorder characterized by a defect in leukocyte adhesion molecules, leading to marked leukocytosis, recurrent infections, and delayed umbilical cord separation.[10] Other causes include congenital anomalies and leukemoid reaction, transient myeloproliferative disorder [TMD] of Down syndrome, familial cold urticaria, and leukocytosis, hereditary chronic neutrophilia (also known as chronic neutrophilic leukemia).[11][12]

Secondary Neutrophilia

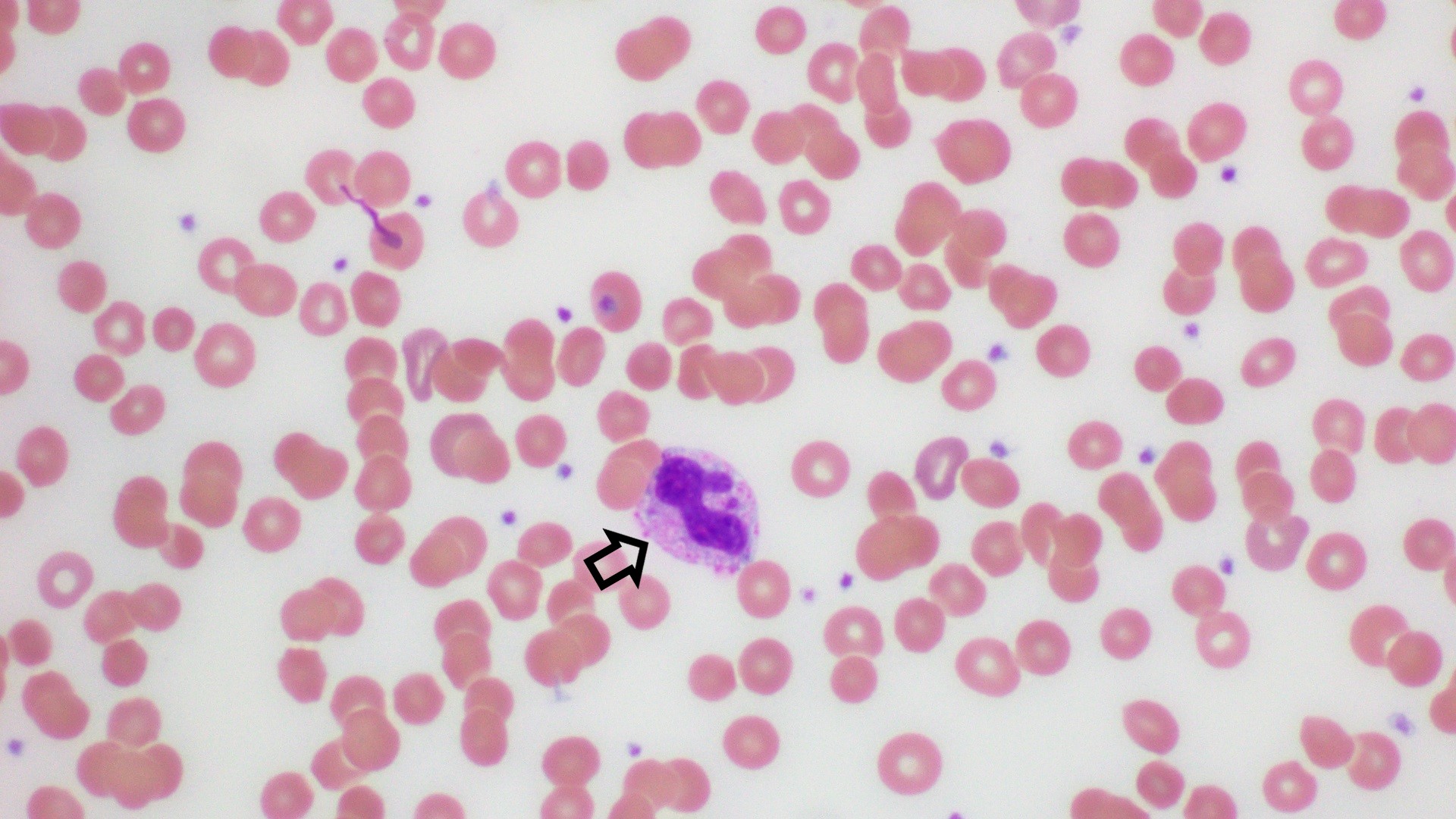

Infection/Inflammation; The most common cause of secondary neutrophilia is infection and inflammation. Bacterial infections are usually associated with left shift (i.e., an increase in the percentage of band forms of leukocytes), toxic granulations, and Döhle bodies on peripheral smear.[13] Whereas viral infections may have a high neutrophil count with atypical lymphocytes. Worth mentioning here is a leukemoid reaction, i.e., WBC count of more than 50,000 cells/microL, caused by various infections such as clostridium difficile, tuberculosis, and medications such as ATRA and some nonhematological malignancies. It is essential to distinguish leukemoid reaction from acute leukemia, which is a hematological malignancy. Both acute and chronic inflammation can lead to neutrophilia, to name a few, including Still disease of young, juvenile, and adult-onset rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatous disease, vasculitis, myositis, chronic hepatitis, and inflammatory bowel disease.[14]

Nonhematological neoplasms: Neutrophilia can be seen in solid tumor malignancies. Mechanisms leading to increased neutrophil count can be a paraneoplastic leukemoid reaction, bone marrow metastasis, nonspecific tumor-related inflammation, infections, and high-dose corticosteroids for tumor therapy.[15]

Medications: Many medications can cause neutrophilia by various mechanisms, some of which are listed below.

- Recombinant granulocyte and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factors (G-CSF or GM-CSF), All-trans retinoic acid; Increase neutrophil count via direct stimulation of bone marrow myelopoiesis.

- Glucocorticoids, Plerixafor; Increase neutrophil count by causing the release of granulocytes from the bone marrow into circulation.

- Other drugs include lithium and catecholamines.

Many medications can cause neutrophilia due to adverse drug reactions, i.e., allergic or inflammatory responses to a drug.

Others: secondary neutrophilia may also result from various stimuli. These stimuli may include physical or emotional stress, vigorous exercise, temperature changes, seizure activity, cigarette smoking, surgery, obesity, asplenia or hyposplenism, and generalized bone marrow stimulation, such as in hemolysis.[16][17][18]

Epidemiology

There is a limitation in predicting which patients are at increased risk of developing neutrophilia, given multiple contributing factors. Certain social factors like smoking status, stress, and exercise level can also impact neutrophilia risk. There are more consistent ethnical differences among patients with neutropenia than neutrophilia patients; relative to white people, black people have a lower total WBC count and lower neutrophil count. However, the Latino population is noted to have a higher leukocyte count (mean difference 0.16×10^9/L) and higher neutrophil count (mean difference 0.11×10^9/L) compared to the white population.[19]

Pathophysiology

Circulating neutrophils are mature neutrophils in transit from the bone marrow into the peripheral blood. The life span of neutrophils in bone marrow is approximately ten days, 2 to 3 days in peripheral tissue, and approximately less than 24 hr. in circulation.[20] The production, proliferation, differentiation, and entry of neutrophils in peripheral blood are tightly regulated by cytokines and controlled by various transcription and growth factors.[21][22][23] Neutrophilia can be due to aberrant neutrophils' production by the bone marrow, demargination of neutrophils into the bloodstream, and reactive response to infection, inflammation, and allergic reaction to the medication.

Histopathology

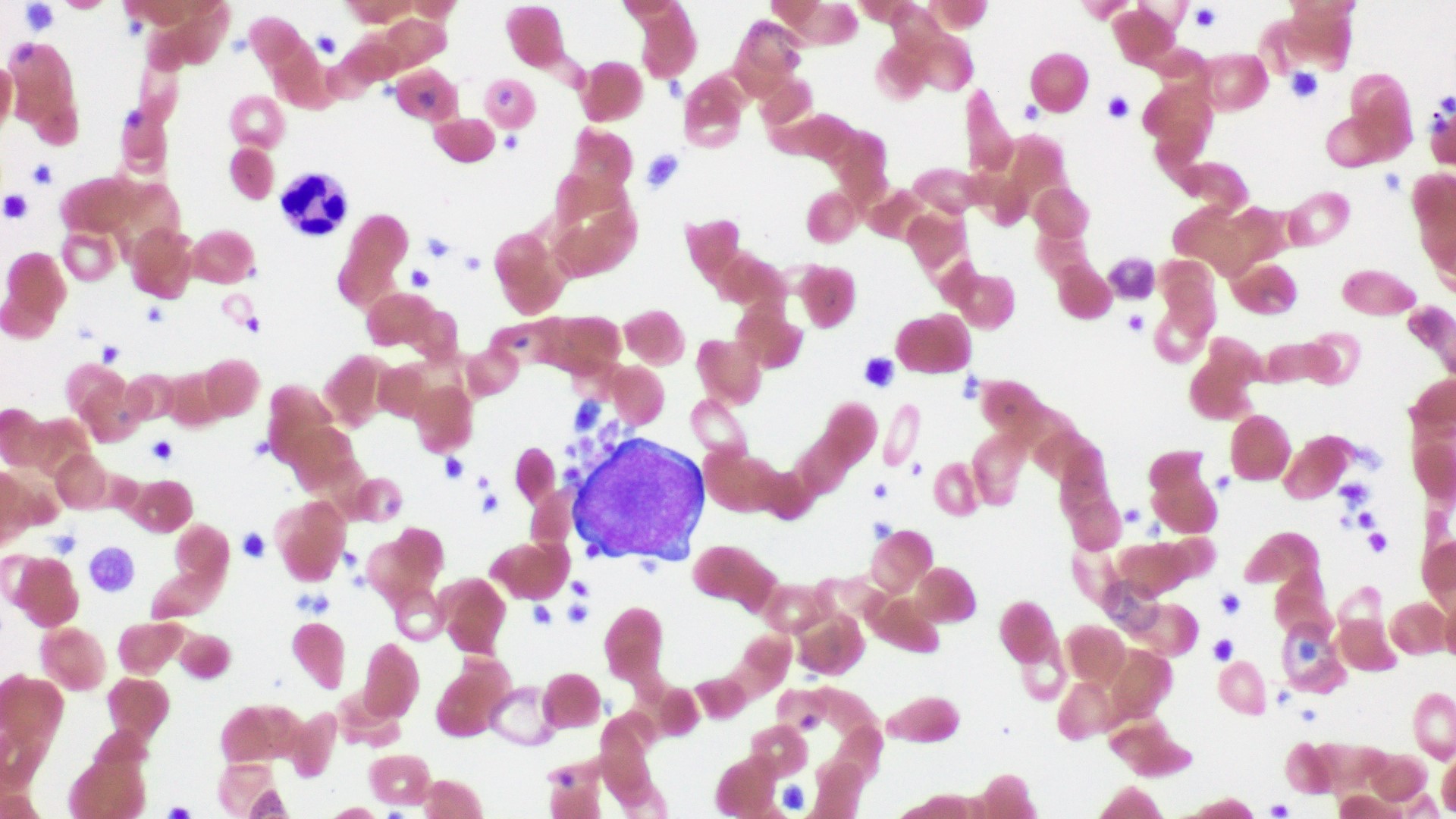

Examination of peripheral blood smears can be beneficial in distinguishing various causes of neutrophilia. Platelet clumping can be seen on peripheral smears in factitious neutrophilia. Myelocytes, metamyelocytes, and increased band forms are seen in severe infections or CML. The presence of toxic granulations and Dohle bodies can also be seen in various infectious and inflammatory states.

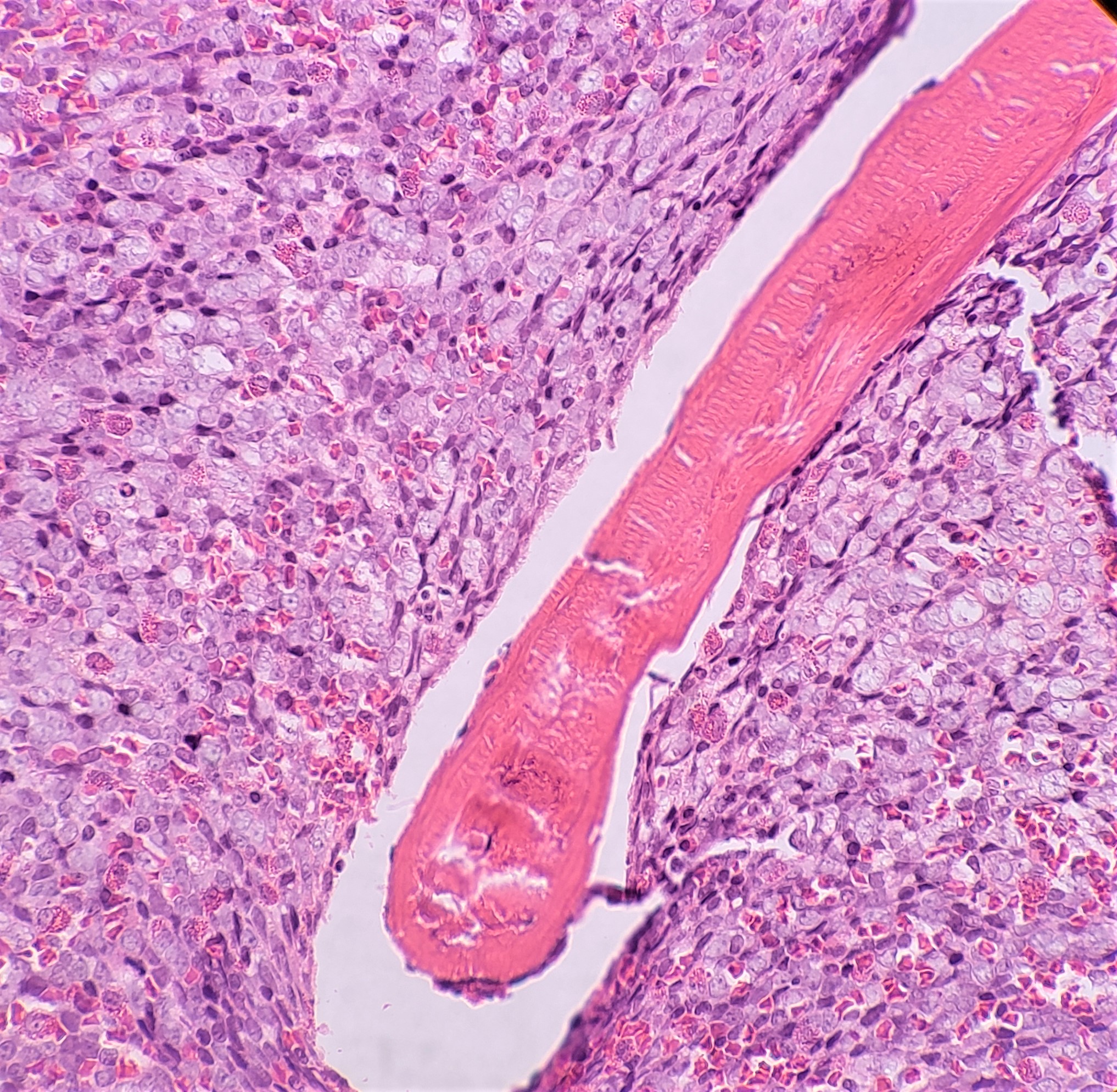

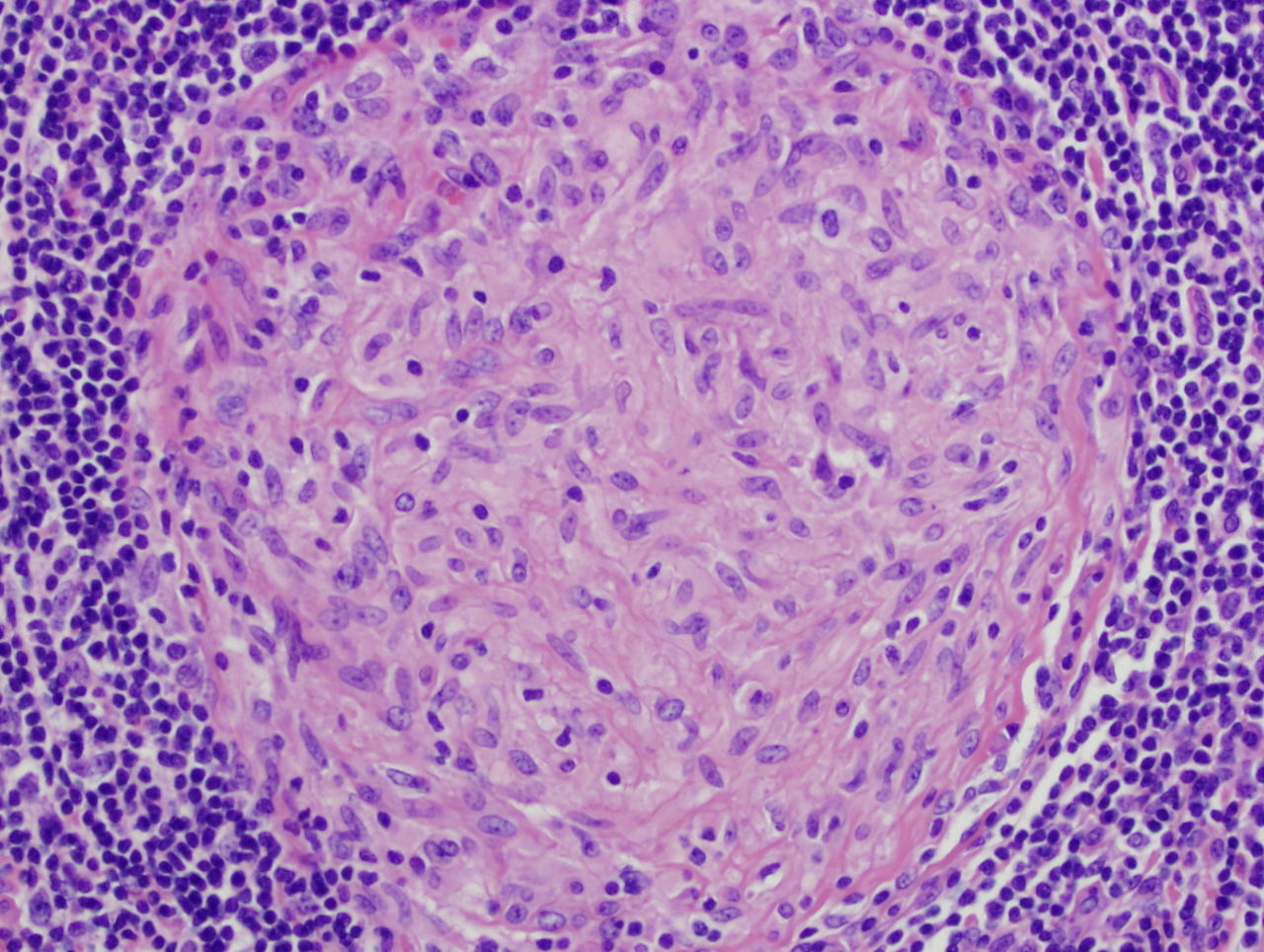

Granulomatous diseases are characterized by granulomata, which are defined as the localized accumulation of activated epithelioid macrophages. In Leukocyte adhesion factor deficiency(LAD), marked neutrophilia accompanied by mild lymphocytosis can be seen even in the absence of any ongoing infection. If there is an ongoing infection, then biopsies of infected tissues can show inflammatory infiltrates devoid of neutrophils.

History and Physical

History should be focused on the following:

- Evidence of active or prior infection and or inflammation

- Prior complete blood count (CBC) results

- Any recent medication changes

- Evaluation of hematological or non-hematological malignancies (recent weight loss, decreased appetite, swollen glands, new palpable mass, generalized body ache, fatigue, night sweats, fever or new cold symptoms, etc.)

- Family history of neutrophilia

- History of vigorous exercise, cigarette smoking, new physical or emotional stress

- History of functional or surgical asplenia

Physical examination, in general, should be comprehensive and focus on ruling out above mentioned history clues.

- Vitals assessment for fever, tachycardia

- Head and neck examination for facial and conjunctival pallor and lymphadenopathy

- Pulmonary examination for decreased breath sounds or any added breath sounds

- Abdominal examination for abdominal distention, tenderness, mass, and hepatosplenomegaly

- Musculoskeletal examination for joints erythema, tenderness, swelling, and or deformity

- Skin examination for any new lesions, nodules, and color changes

Clinical manifestations in LAD are periodontitis, recurrent skin and mucosal infections, absent pus formation, poor wound healing, and delayed umbilical cord separation.

Evaluation

CBC and peripheral blood smear: Evaluation of neutrophilia can be started by reviewing CBC with differential and confirming automated differential with a manual by reviewing peripheral blood smear. A peripheral blood smear review can also help differentiate causes of neutrophilia, as mentioned above in the histopathology section.

Other Laboratory Studies

Certain laboratory studies can help us distinguish primary versus reactive neutrophilia, such as

- Inflammatory markers, including ESR, CRP, LDH, ferritin

- Liver and renal function tests.

- Coagulation profile including APTT, PT/INR, fibrinogen, D dimer

- Blood culture, sputum culture, urine culture, wound culture, stool culture, and cerebrospinal fluid analysis (chemistry, histopathology, and culture).

- Clostridium difficile testing

Special Tests

Other tests that can help diagnose neutrophilia once CBC and peripheral blood smear have been reviewed are bone marrow biopsy, flow cytometry, and molecular/genetic testing.

- Bone marrow biopsy helps establish the diagnosis of various hematological and non-hematological malignancies invading bone marrow. The biopsy can be utilized to run morphological analysis, flow cytometry, and molecular testing.

- Flow cytometry can help diagnose various MPNs, such as CML, PV, and ET, by immunophenotyping peripheral blood.

- LAD can be diagnosed by molecular testing and or flow cytometry.

Imaging

Imaging that can help differentiate causes of neutrophilia include.

- Computed tomography (CT) of the head and neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis.

- Magnetic resonance imaging of the head and neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis if CT was inconclusive

- Positron emission test PET scan

- Chest Radiography

- Diagnostic ultrasonography

Treatment / Management

Treatment of neutrophilia is based on treating the underlying cause of neutrophilia. In a leukemoid reaction where the WBC count is more than 50,000, emergent leucopheresis, aggressive hydration, and cytotoxic therapy with hydroxyurea are indicated to prevent hypercoagulability-associated complications. Antibiotic and anti-inflammatory therapies should be undertaken for neutrophilia associated with infection/inflammation.

Medications noted to cause neutrophilia should be carefully monitored and may need to be discontinued if leading to complications. MPNs are usually treated with cytoreductive drugs; the commonly used is hydroxyurea with serial monitoring of CBC. Specific treatment options for CML include tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy with imatinib which inhibits bcr-abl tyrosine kinase, the abnormal gene product of Philadelphia chromosome t (9;22) in CML, and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HCT).[24][25][26] (A1)

Referral to a hematologist should be considered as a part of the workup for MPNs.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of neutrophilia includes:

- Infections including bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic

- Acute and chronic inflammation, e.g., granulomatous diseases, vasculitis, inflammatory bowel disease

- Leukemoid reaction

- Hematological and non-hematological malignancies

- Medications

- Asplenia or hyposplenia

- Physical and emotional stimuli (stress, active smoking, vigorous exercise, pregnancy, obesity)

- Tissue damage, e.g., surgery, trauma, burns

- Laboratory artifacts

- Inherited causes like LAD, hereditary neutrophilia

Prognosis

The prognosis of neutrophilia depends on the prognosis of the underlying cause of neutrophilia. Neutrophilia seen in infection/inflammatory state resolves with treatment of these states. Neutrophilia associated with medications can also resolve once either treatment is over or the drug is discontinued. The prognosis in CML has been drastically improved with the introduction of TKIs, including Imatinib and HCT.[27] HCT has also successfully improved survival in LAD patients.[28]

Complications

Complications of neutrophilia are those that are of the causes of neutrophilia, such as

- Hypercoagulability associated with leukemoid reactions

- Bacteremia, septic shock, and multiorgan failure in untreated infections

- Impaired wound healing, severe periodontitis, severe mental impairment, and failure to thrive in untreated LAD

- Thrombosis, hemorrhage, transformation to acute leukemia, and fibrosis are seen in untreated MPNs[29][30]

Consultations

An infectious disease specialist should evaluate patients with infection-associated neutrophilia both in inpatient and outpatient settings. Hematology/Oncology consultation should be considered in patients with hematological and non-hematological malignancies associated with neutrophilia. To rule out LAD, a pediatric consultation should be considered in children presenting with poor wound healing, periodontitis, and repetitive infections.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Educate patients about smoking cessation, weight loss, balanced diet, and relaxation techniques for neutrophilia seen in various physical and emotional stimuli. Educate patients about the side effects of medications like ATRA, lithium, and G CSF that can cause neutrophilia.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Due to the complexity of this condition, management of neutrophilia-associated conditions requires an interprofessional team of health care professionals, including hospital physicians, primary care physicians, specialists including infectious disease specialists, hematologists/oncologists, pediatricians, microbiologists, specialty-trained nurses, and pharmacists working together collaboratively to enhance patient-centered care and improve outcomes. Specialists should recommend treatment options, including antimicrobials, cytoreductive therapies, leucopheresis, immunotherapy, and HCT. Pharmacists should review the indication, dosage, interactions, and contraindications of medications. Nurses taking care of these patients should monitor signs and symptoms associated with neutrophilia-related conditions and report emergent concerns to hospitalists and specialists. Thus, the morbidity and mortality related to neutrophilia-related conditions can be lowered through an interprofessional team approach. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Picture of a granuloma (without necrosis) as seen through a microscope on a glass slide. The tissue on the slide is stained with two standard dyes (hematoxylin: blue, eosin: pink) to make it visible. The granuloma in this picture was found in a lymph node of a patient with Mycobacterium avium infection. Contributed by Wikimedia Commons, Sanjay Mukhopadhyay (Public Domain)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kobayashi Y, The role of chemokines in neutrophil biology. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library. 2008 Jan 1; [PubMed PMID: 17981721]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKolaczkowska E,Kubes P, Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2013 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 23435331]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHollowell JG,van Assendelft OW,Gunter EW,Lewis BG,Najjar M,Pfeiffer C,Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics., Hematological and iron-related analytes--reference data for persons aged 1 year and over: United States, 1988-94. Vital and health statistics. Series 11, Data from the National Health Survey. 2005 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 15782774]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSolanki DL,Blackburn BC, Spurious leukocytosis and thrombocytopenia. A dual phenomenon caused by clumping of platelets in vitro. JAMA. 1983 Nov 11; [PubMed PMID: 6632146]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSavage RA, Pseudoleukocytosis due to EDTA-induced platelet clumping. American journal of clinical pathology. 1984 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 6422738]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePatel KJ,Hughes CG,Parapia LA, Pseudoleucocytosis and pseudothrombocytosis due to cryoglobulinaemia. Journal of clinical pathology. 1987 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 3818970]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWard HN,Reinhard EH, Chronic idiopathic leukocytosis. Annals of internal medicine. 1971 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 5558646]

Tefferi A, Chronic myeloid disorders: Classification and treatment overview. Seminars in hematology. 2001 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 11242595]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArber DA,Orazi A,Hasserjian R,Thiele J,Borowitz MJ,Le Beau MM,Bloomfield CD,Cazzola M,Vardiman JW, The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016 May 19; [PubMed PMID: 27069254]

Etzioni A, Genetic etiologies of leukocyte adhesion defects. Current opinion in immunology. 2009 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 19647987]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceElliott MA,Tefferi A, Chronic neutrophilic leukemia: 2018 update on diagnosis, molecular genetics and management. American journal of hematology. 2018 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 29512199]

Weinstein HJ, Congenital leukaemia and the neonatal myeloproliferative disorders associated with Down's syndrome. Clinics in haematology. 1978 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 148990]

Wanahita A,Goldsmith EA,Musher DM, Conditions associated with leukocytosis in a tertiary care hospital, with particular attention to the role of infection caused by clostridium difficile. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2002 Jun 15; [PubMed PMID: 12032893]

Caprilli R,Corrao G,Taddei G,Tonelli F,Torchio P,Viscido A, Prognostic factors for postoperative recurrence of Crohn's disease. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio del Colon e del Retto (GISC) Diseases of the colon and rectum. 1996 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 8603558]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGranger JM,Kontoyiannis DP, Etiology and outcome of extreme leukocytosis in 758 nonhematologic cancer patients: a retrospective, single-institution study. Cancer. 2009 Sep 1; [PubMed PMID: 19551882]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChristensen RD,Hill HR, Exercise-induced changes in the blood concentration of leukocyte populations in teenage athletes. The American journal of pediatric hematology/oncology. 1987 Summer; [PubMed PMID: 2954481]

McCarthy DA,Perry JD,Melsom RD,Dale MM, Leucocytosis induced by exercise. British medical journal (Clinical research ed.). 1987 Sep 12; [PubMed PMID: 3117270]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMcBride JA,Dacie JV,Shapley R, The effect of splenectomy on the leucocyte count. British journal of haematology. 1968 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 5635603]

Hsieh MM,Everhart JE,Byrd-Holt DD,Tisdale JF,Rodgers GP, Prevalence of neutropenia in the U.S. population: age, sex, smoking status, and ethnic differences. Annals of internal medicine. 2007 Apr 3; [PubMed PMID: 17404350]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTak T,Tesselaar K,Pillay J,Borghans JA,Koenderman L, What's your age again? Determination of human neutrophil half-lives revisited. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2013 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 23625199]

Lichtman MA,Chamberlain JK,Weed RI,Pincus A,Santillo PA, The regulation of the release of granulocytes from normal marrow. Progress in clinical and biological research. 1977; [PubMed PMID: 400761]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTenen DG,Hromas R,Licht JD,Zhang DE, Transcription factors, normal myeloid development, and leukemia. Blood. 1997 Jul 15; [PubMed PMID: 9226149]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKaushansky K, Lineage-specific hematopoietic growth factors. The New England journal of medicine. 2006 May 11; [PubMed PMID: 16687716]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHydroxyurea versus busulphan for chronic myeloid leukaemia: an individual patient data meta-analysis of three randomized trials. Chronic myeloid leukemia trialists' collaborative group. British journal of haematology. 2000 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 10997966]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGoldman JM,Apperley JF,Jones L,Marcus R,Goolden AW,Batchelor R,Hale G,Waldmann H,Reid CD,Hows J, Bone marrow transplantation for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 1986 Jan 23; [PubMed PMID: 3510388]

Goldman JM,Majhail NS,Klein JP,Wang Z,Sobocinski KA,Arora M,Horowitz MM,Rizzo JD, Relapse and late mortality in 5-year survivors of myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia in first chronic phase. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010 Apr 10; [PubMed PMID: 20212247]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBower H,Björkholm M,Dickman PW,Höglund M,Lambert PC,Andersson TM, Life Expectancy of Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Approaches the Life Expectancy of the General Population. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016 Aug 20; [PubMed PMID: 27325849]

Qasim W,Cavazzana-Calvo M,Davies EG,Davis J,Duval M,Eames G,Farinha N,Filopovich A,Fischer A,Friedrich W,Gennery A,Heilmann C,Landais P,Horwitz M,Porta F,Sedlacek P,Seger R,Slatter M,Teague L,Eapen M,Veys P, Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for leukocyte adhesion deficiency. Pediatrics. 2009 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 19255011]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceElliott MA,Tefferi A, Thrombosis and haemorrhage in polycythaemia vera and essential thrombocythaemia. British journal of haematology. 2005 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 15667529]

Noor SJ,Tan W,Wilding GE,Ford LA,Barcos M,Sait SN,Block AW,Thompson JE,Wang ES,Wetzler M, Myeloid blastic transformation of myeloproliferative neoplasms--a review of 112 cases. Leukemia research. 2011 May; [PubMed PMID: 20727590]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence