Introduction

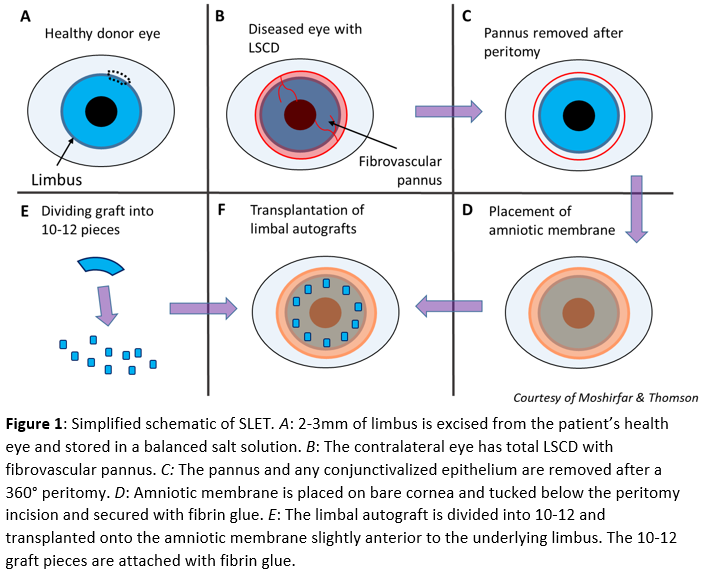

Sangwan et al. first described simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET) in 2012; it is a procedure for unilateral limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) treatment to restore normal corneal epithelium. SLET involves sectorial harvesting of the limbus from the patient’s healthy contralateral eye to be sectioned into 8-12 smaller limbal autografts. After the removal of any abnormal corneal epithelium and fibrovascular pannus from the diseased eye, an amniotic membrane is placed on the cornea, and the limbal autografts are transplanted onto the membrane followed by a bandage cornea lens.[1][2][3]

The amniotic membrane is used because it contains growth factors and possesses antiangiogenic, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anti-scarring properties that promote the expansion of stem cells and migration of epithelial cells before inflammation and scarring can curtail regeneration.[4]

Allogenic SLET

Allogeneic SLET is similar to autologous SLET except that it uses limbal grafts from cadavers or living donors and may be used to treat bilateral LSCD. Current data has not found a significant difference in outcomes after the use of tissue from either living or cadaveric donors. Allogenic SLET has also been used to achieve rapid surface epithelialization in acute chemical burns.[5]

Patients with allografts from any source require postoperative intravenous immunosuppression followed by long-term systemic immunosuppression, most often cyclosporine, and topical steroid drops to ensure graft survival.[6] When compared to autologous SLET, allogenic SLET has the downside of requiring immunosuppression. Still, it is a treatment for patients who cannot undergo autologous SLET due to bilateral LSCD from a systemic etiology or injury to both eyes.[7][8]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The ocular surface has two types of epithelial cells that populate the corneal and conjunctival surfaces. The border of these cell types is the corneoscleral limbus. Stem cells for corneal epithelium are found in the basal cell layer of limbal epithelial ridges called the palisades of Vogt, although not exclusively. These papillary epithelial structures are heavily pigmented to protect from UV radiation and provides a microenvironment conducive for stem cell survival and function. The palisades of Vogt may be visualized, extending radially into the bulbar conjunctiva with slit-lamp microscopy.[9][10]

The palisades of Vogt and consequently, limbal stem cells are found in higher concentrations in the superior and inferior limbal regions and less so in the nasal and temporal regions. This observation may be explained by the added protection eyelids offer to these regions from insults such as chemical agents or UV radiation.[11]

Proliferation and asymmetric division of these limbal stem cells produce cells that migrate centripetally and anteriorly and eventually terminally differentiate and desquamate off the corneal surface. This maintains corneal epithelial integrity and heals epithelial defects. These stem cells also have the critical role of preventing the surrounding bulbar conjunctival epithelium from invading the corneal surface.[12][13]

Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency (LSCD)

LSCD is an ocular surface disease resulting from depletion or dysfunction of the limbal stem cells, thus leading to corneal inflammation, vascularization, and pannus formation. However, these pathologies are seen in many disease processes other than LSCD. A characteristic feature of LSCD is conjunctivalization. Conjunctivalization is the result of conjunctival epithelium invasion and subsequent transformation into an epithelium composed of conjunctival epithelial cells with or without neovascularization or a metaplastic mixture of corneal and conjunctival cells. The invading conjunctival tissue may even lose goblet cells, normally seen in conjunctival epithelium.

Depending on the degree of stem cell damage, the corneal surface may have incomplete conjunctivalization with some normal limbus and corneal epithelium remaining seen in partial LSCD. In total LSCD, the entire corneal surface may be enveloped by conjuntivalized epithelium. The pathologic epithelium is thinner and more permeable to large molecules, which allows for the differentiation between normal and abnormal epithelium with fluorescein staining. Patients with LSCD may be asymptomatic or present with decreased vision, corneal discomfort, pain, recurrent epithelial erosions, and infections.[14][15]

The causes of LSCD may be hereditary or acquired.

- Acquired and non-immune-mediated causes include chemical and thermal burns, contact lens-induced LSCD, surgery involving the limbus, drug toxicity, bullous keratopathy, and infectious keratopathy.

- Immune-mediated causes include Stevens-Johnson syndrome, mucous membrane pemphigoid, vernal keratoconjunctivitis, atopic keratoconjunctivitis, and graft-vs-host disease.

- Hereditary causes include congenital aniridia, xeroderma pigmentosa, dyskeratosis congenita, and epidermolysis bullosa.[14]

Indications

Simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET) has been proven to be a successful treatment for both total and partial LSCD.[2] One absolute requirement is a healthy contralateral eye to harvest limbal stem cells. A majority of uniocular cases are secondary to chemical and thermal burns.[3] Of note, SLET is a treatment for epithelial pathology only. If severe stromal opacification is present, penetrating or lamellar keratoplasty is ideally performed electively at a later date after SLET. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography is a beneficial test to evaluate corneal stromal thickness and opacification.[7]

There is no consensus on the diagnostic criteria for LSCD. Most cases are diagnosed clinically. The “gold standard” diagnostic test is impression cytology, which evaluates cells collected from the cornea surface for the presence of goblet cells or features of the conjunctival epithelium. Non-invasive in vivo confocal microscopy has also been used to diagnose and monitor LSCD.[16]

Fluorescein staining is very useful for diagnosing and evaluating LSCD. Unlike most epithelial defects, the more permeable conjunctivalized epithelium has delayed staining, which remains for ten or more minutes even after rinsing with eyewash solutions. The conjunctivalized epithelium is also thinner than normal corneal epithelium leading to pooling of the fluorescein dye that may demarcate normal and pathologic epithelium.[14]

The distribution of limbal palisades of Vogt may diminish with age. However, observing flattening or disappearance of the palisades, particularly in the superior limbus or an area known to have them may be a sign of stem cell loss.[12][14]

Contraindications

Simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET) may not be appropriate for some systemic causes of LSCD because stem cell harvesting may induce LSCD. History of trauma, infection, or surgery in the donor's eye may also predispose to inducing LSCD after harvesting. Contact lens wear has been known to induce LSCD, but contact lens-induced LSCD cases are usually not as severe as other causes. However, SLET could potentially cause symptomatic LSCD in the donor eyes of patients who wear contact lenses.[17] In the setting of bilateral LSCD, allogenic SLET is a potential option, but it will require long-term systemic immunosuppression, which may be inappropriate for pediatric patients.

Absolute contraindications for SLET include any of the following in the recipient's eye:

- Dry ocular surface, e.g., keratinization of corneal or conjunctival epithelium or a positive Schirmer's defined as <10 mm with anesthesia)

- Blindness with no potential for vision restoration

- The disorganized anterior segment, e.g., extensive peripheral anterior synechiae, anterior staphyloma, or adherent leukoma

- Untreated adnexal pathology, e.g., lagophthalmos, dacryocystitis, trichiasis, entropion.[7]

Equipment

Following types of equipment are required while performing simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET)

- Essential eye operating room equipment

- Access to amniotic membranes

- Fibrin glue

Personnel

Simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET) may be performed with the

- Operating ophthalmologist

- Assistant

- Scrub tech

- Circulating nurse

- Anesthesiologist

Preparation

The cause of the patient’s LSCD may pose a risk of inducing LSCD in the donor eye, so it is essential to take a good history. Fluorescein staining will allow visualization of pathologic corneal epithelium that requires removal. Patients suffering from unilateral LSCD should have normal vision in their healthy eye. Patient counseling and informed consent are needed when proposing the idea of performing a biopsy on their only good eye.

Depending on the particular case and complications, patients should be informed of the possibility of requiring subsequent surgeries. Aesthetic results from simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET) will never match a normal eye, so it is essential to set a patient’s expectations and focus on improvement from the eye’s preoperative state. Preoperative vasoconstriction with 2 to 3 drops of phenylephrine 5% and brimonidine tartrate 0.15% in both eyes is recommended to reduce intraoperative bleeding.

When planning to perform allogenic SLET using cadaveric tissue, the graft should ideally be fresh (less than 48 hrs from harvesting), have visible limbal palisades, have no observable epithelial sloughing, and be collected from a cadaver aged 60-years-old or less.[7]

Technique or Treatment

Simple Limbal Epithelial Transplantation (SLET)

In children, general anesthesia is advised. For adults, a local or topical anesthetic is administered to the donor eye, and a 2 to 3 mm length of the healthy limbus is excised, usually at the superior limbus. One millimeter peripheral to the superior limbus, Vannas scissors, is used to develop a flap of the conjunctiva and dissected to the limbus. A number 15 blade completes the dissection approximately 1mm into the clear peripheral cornea. This flap is excised and stored in a balanced salt solution (Fig. 1A). If a large symblepharon is present and removed from the diseased eye, more conjunctiva may be excised from the healthy eye to graft the site.

A 360° peritomy is performed on the diseased eye, and a keratectomy removes the fibrovascular pannus. Any normal healthy corneal and limbal epithelium present on the diseased eye is left untouched (Fig. 1B&C). An amniotic membrane is placed stroma side down and epithelial side up on the bare cornea. The membrane should cover the cornea and sclera up to the peritomy incision to be tucked below the conjunctival edge. The membrane is smoothed with surgical instruments, and fibrin glue allows the membrane to adhere to the optical surface (Fig. 1D).

Using Vannas scissor or a blade and cutting board, the limbal graft is cut into 10 to 12 equal-sized pieces (Fig. 1E). These pieces are transplanted onto the membrane just inside the underlying limbus (Fig. 1F). Whether or not maintaining the grafts’ original orientation is beneficial is not known, although some surgeons attempt to achieve original orientation using the limbal pigments as a guide. Fibrin glue is applied for graft adherence, and a bandage contact lens is applied, although cryopreserved amniotic membranes have also been employed.[18] In young children, a suture tarsorrhaphy for the first couple of weeks may be appropriate to prevent early loss of the transplant or bandage contact lens. If suture tarsorrhaphy is utilized, topical antibiotic-steroid ointments and oral steroids to reduce peri-ocular edema should be prescribed until suture removal.

If the corneal stroma under the pannus is too thin and perforates, penetrating keratoplasty may be performed. Penetrating keratoplasty has also been used simultaneously with SLET, but ideally, this is done electively at a later date as it increases the chance of graft failure.

The bandage contact lens is removed on the seventh postoperative day. If complete epithelial healing is not observed with fluorescein staining, a bandage contact lens is used for an additional week. Healing of the defect in the donor eye should also be monitored. While using the contact lens, topical ciprofloxacin 0.3% drops are instilled four times daily. Topical prednisolone acetate 1% drops six times daily is used for one week then tapered by one drop a day every week for six weeks for both eyes.[3][7]

Allogenic SLET will require long-term oral or pulse intravenous immunosuppression regimens, or else the grafts will eventually reject. The pulse intravenous regimen starts with 500mg IV methylprednisolone on the day of surgery and repeat administration at one-week post-op. This is followed by injections every six weeks until six months post-op, then every two months until one-year post-op, then every three months until two years post-op, and finally, every six months after that. Oral prednisone is started at 1mg/kg and tapered weekly to 5 mg/day. Patients will also require oral cyclosporine 5 to 7 mg/kg 48 hours pre-op and 1g IV for post-op days 0 to 3. Cyclosporine is then tapered to 1.5 to 2 mg/kg maintenance dose over 4 to 8 weeks, with 90mg of diltiazem hydrochloride to reduce the cost and increase serum cyclosporine levels. Regimens with mofetil and tacrolimus have also been successful.[6] Hepatic, renal, hematologic testing will need to be performed every 4 to 6 weeks. Topical steroid eye drops can be tapered to a maintenance dose of 1 to 2 times/day but can never be tapered off completely.[7]

Other Surgical Techniques

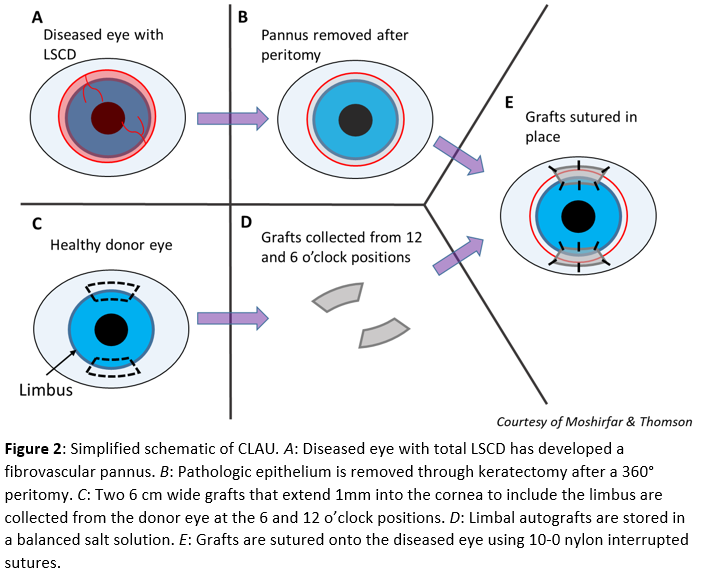

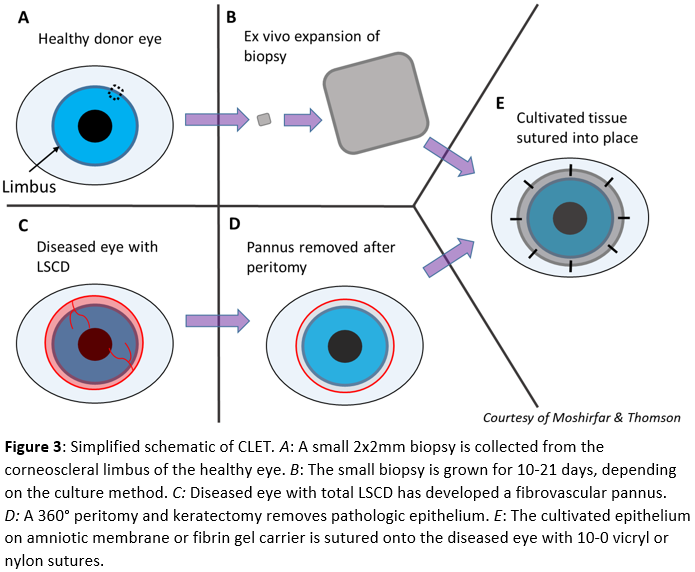

Other autologous limbal stem cell transplantation techniques that have successfully treated LSCD include conjunctival limbal autograft (CLAU), introduced in 1964 and further developed in 1989 by Kenyon and Tseng (Fig. 2) and cultivated limbal epithelial transplantation (CLET) introduced by Pellegrini et al. in 1997 (Fig. 3). These will be discussed briefly.[19][20] Techniques that utilize allogenic sources for limbal stem cells include allogenic SLET, living-related conjunctival-limbal allograft, and keratolimbal allograft.

Conjunctival Limbal Autograft (CLAU)

CLAU is performed by removing the fibrovascular pannus from the diseased eye after a peritomy and superficial keratectomy (Fig. 2A, 2B). From the 12 and 6 o’clock positions, two limbal grafts 6 mm in length (approximately 3-hour sized quadrants) and 2 to 4 mm posteriorly into the conjunctiva and 1 mm anteriorly into the cornea is harvested (Fig. 2C) and stored in a balanced salt solution (Fig. 2D). Two 10-0 vicryl sutures are used to close the donor sites. The grafts are transplanted to the diseased eye near the limbal edge at the 12 and 6 o’clock position. The grafts are secured with 10-0 nylon interrupted sutures (Fig. 2E).[19][21]

Cultivated Limbal Epithelial Transplantation (CLET)

CLET starts by harvesting a 2x2 mm biopsy from the corneoscleral limbus (Fig. 3A). The collected tissue is grown either by placing the whole biopsy on an amniotic membrane in a liquid culture medium or in a suspension culture that is later seeded onto an amniotic membrane or culture dish. A fibrin gel carrier may be used to transfer the epithelial sheet to the ocular surface. This ex-vivo expansion takes between 10-21 days to complete depending on the method (Fig. 3B). Once the cultivated tissue is sufficient for transplantation, a peritomy and keratectomy remove the fibrovascular pannus from the diseased eye (Fig. 3C, 3D). The graft is placed with cultured epithelium facing anteriorly and secured with 10-0 vicryl or nylon sutures (Fig. 3E).[20][22]

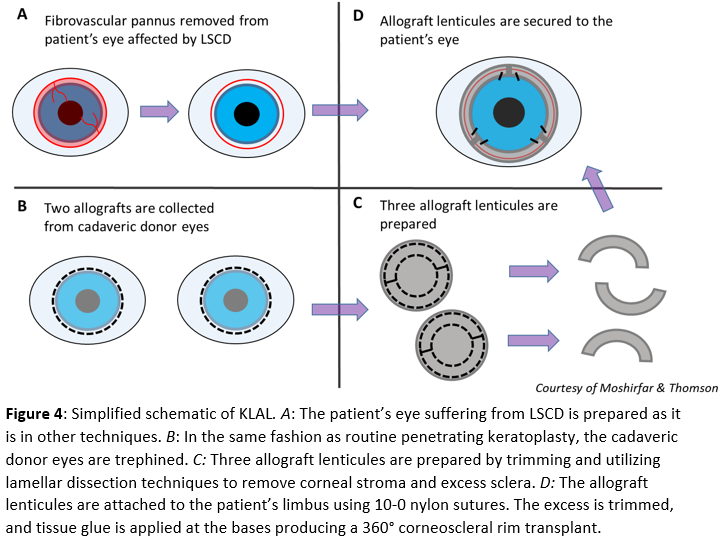

Living-Related Conjunctival Limbal Allograft (LR-CLAL) and Keratolimbal Allograft (KLAL)

Living-related conjunctival limbal allograft (LR-CLAL) is a procedure that is similar to CLAU (Fig. 2) except that the limbal tissue source is from a living relative rather than the patient’s contralateral eye. Keratolimbal allograft (KLAL) a similar procedure except the limbal stem cell source is a cadaver, and the harvested grafts are much larger (Fig. 4). For KLAL, the corneoscleral rims of both cadaveric donor eyes are trephined, similar to routine penetrating keratoplasty (Fig. 4B). Next, the rims are cut in two and trimmed, leaving 2 to 3 mm of the sclera. Corneal stroma and extra sclera are excised using lamellar dissection techniques.

The result is three 6-hour long allograft lenticules (Fig. 4C). Pathologic epithelium is removed from the patient’s eye in the same fashion as other techniques (Fig. 4A). The grafts are sutured to the limbus with two 10-0 nylon, and excess graft is trimmed, such that there is no overlap. Finally, the base of each graft is secured with tissue glue (Fig. 4D). For severe cases of the conjunctival and limbal disease, a combined KLAL and LR-CLAL or CLAU procedure referred to as the “Cincinnati procedure” combines the benefits of a large conjunctival graft produced by LR-CLAL or CLAU and a large limbal graft produced by KLAL. These procedures may treat bilateral LSCD, but require long-term systemic immunosuppression because the allogenic grafts are at risk of rejection.[23][24]

Complications

Significant risk factors associated with simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET) failure include the following:

- Chemical burns

- Symblepharon presence before surgery and simultaneous SLET

- Penetrating keratoplasty.

Failure most often occurs within six months after surgery. Significant complications in the donor eye have not been observed.

The most common complication seen in the treated eye is focally recurrent LSCD. If the recurrent LSCD is not progressing or affecting the visual axis, it may be monitored, and repeat SLET has successfully treated recurrent LSCD.

Hemorrhage under the amniotic membrane may occur, but often resolves or only requires drainage via a needle puncture.

Sterile or infectious keratitis may develop and has been described to respond well to treatment and topical antibiotics. If superficial corneal haze is present, topical cyclosporine 0.05% drops are prescribed for several months.

Complications that may cause graft failure include progressive conjunctivalization, symblepharon, and loss of donor tissue attached to the bandage contact lens.

Rare complications include corneal neovascularization, epithelial hyperplasia, and PED. Allogenic SLET will have a risk of immunologic rejection that may be treated with an increased dose of intravenous and oral Immunosuppressants.[7][25]

Clinical Significance

Basu et al. published the long-term outcomes of simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET) on a population of 125 patients consisting of 65 adults and 60 children with unilateral LSCD. Successful outcomes were maintained in 76% of the eyes with a survival probability of 80% in adults and 72% in children after 12 months.[2] A retrospective, multicenter study by Vazirani et al. with a 6-month follow-up found 83.8% of cases achieved clinical success with a survival probability of 80%.[26]

When compared with other surgical treatments of LSCD, SLET requires much less donor tissue than CLAU. Other advantages of SLET over CLET include the following:

1. No requirements for a laboratory

2. A single-stage procedure

3. More affordability[27]

A meta-analysis of 22 non-comparative case series, including 1023 eyes, evaluated anatomic and functional outcomes of the three techniques SLET, CLAU, and CLET. The results of this review found clinical outcomes of SLET and CLAU exceed those of CLET with the anatomical and functional success of SLET (78%; 68.6%), CLAU (81%; 74.4%), and CLET (61.4%; 53%; p=0.0048). Note that the group had the lowest study quality and sample size of the three, which may explain the success rates observed.[28]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET) is an effective treatment for unilateral LSCD. Clear communication with the patient or referring provider is essential to establish the underlying cause of LSCD. SLET is also a more affordable and less complicated alternative to CLET, so it may prove to be the ideal treatment for patients in areas with inadequate resources. SLET utilizes an autologous transplant and does not require immunosuppression; however, allogenic SLET will require coordinated care among the health care team to monitor and treat any adverse reactions from immunosuppression.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Sangwan VS, Basu S, MacNeil S, Balasubramanian D. Simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET): a novel surgical technique for the treatment of unilateral limbal stem cell deficiency. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2012 Jul:96(7):931-4. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301164. Epub 2012 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 22328817]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBasu S, Sureka SP, Shanbhag SS, Kethiri AR, Singh V, Sangwan VS. Simple Limbal Epithelial Transplantation: Long-Term Clinical Outcomes in 125 Cases of Unilateral Chronic Ocular Surface Burns. Ophthalmology. 2016 May:123(5):1000-10. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.12.042. Epub 2016 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 26896125]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSangwan VS, Sharp JAH. Simple limbal epithelial transplantation. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2017 Jul:28(4):382-386. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000377. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28406800]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSabater AL, Perez VL. Amniotic membrane use for management of corneal limbal stem cell deficiency. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2017 Jul:28(4):363-369. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000386. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28426442]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIyer G, Srinivasan B, Agarwal S, Tarigopula A. Outcome of allo simple limbal epithelial transplantation (alloSLET) in the early stage of ocular chemical injury. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2017 Jun:101(6):828-833. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-309045. Epub 2016 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 28407620]

Serna-Ojeda JC, Basu S, Vazirani J, Garfias Y, Sangwan VS. Systemic Immunosuppression for Limbal Allograft and Allogenic Limbal Epithelial Cell Transplantation. Medical hypothesis, discovery & innovation ophthalmology journal. 2020:9(1):23-32 [PubMed PMID: 31976340]

Shanbhag SS, Patel CN, Goyal R, Donthineni PR, Singh V, Basu S. Simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET): Review of indications, surgical technique, mechanism, outcomes, limitations, and impact. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2019 Aug:67(8):1265-1277. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_117_19. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31332106]

Bhalekar S, Basu S, Sangwan VS. Successful management of immunological rejection following allogeneic simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET) for bilateral ocular burns. BMJ case reports. 2013 Mar 14:2013():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009051. Epub 2013 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 23505089]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYoon JJ, Ismail S, Sherwin T. Limbal stem cells: Central concepts of corneal epithelial homeostasis. World journal of stem cells. 2014 Sep 26:6(4):391-403. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v6.i4.391. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25258661]

Le Q, Xu J, Deng SX. The diagnosis of limbal stem cell deficiency. The ocular surface. 2018 Jan:16(1):58-69. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.11.002. Epub 2017 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 29113917]

Le Q, Yang Y, Deng SX, Xu J. Correlation between the existence of the palisades of Vogt and limbal epithelial thickness in limbal stem cell deficiency. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2017 Apr:45(3):224-231. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12832. Epub 2016 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 27591548]

Dua HS, Azuara-Blanco A. Limbal stem cells of the corneal epithelium. Survey of ophthalmology. 2000 Mar-Apr:44(5):415-25 [PubMed PMID: 10734241]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEbrahimi M, Taghi-Abadi E, Baharvand H. Limbal stem cells in review. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research. 2009 Jan:4(1):40-58 [PubMed PMID: 23056673]

Deng SX, Borderie V, Chan CC, Dana R, Figueiredo FC, Gomes JAP, Pellegrini G, Shimmura S, Kruse FE, and The International Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency Working Group. Global Consensus on Definition, Classification, Diagnosis, and Staging of Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency. Cornea. 2019 Mar:38(3):364-375. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001820. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30614902]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTseng SC. Concept and application of limbal stem cells. Eye (London, England). 1989:3 ( Pt 2)():141-57 [PubMed PMID: 2695347]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLe Q, Chauhan T, Deng SX. Diagnostic criteria for limbal stem cell deficiency before surgical intervention-A systematic literature review and analysis. Survey of ophthalmology. 2020 Jan-Feb:65(1):32-40. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2019.06.008. Epub 2019 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 31276736]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRossen J, Amram A, Milani B, Park D, Harthan J, Joslin C, McMahon T, Djalilian A. Contact Lens-induced Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency. The ocular surface. 2016 Oct:14(4):419-434. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2016.06.003. Epub 2016 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 27480488]

Amescua G, Atallah M, Nikpoor N, Galor A, Perez VL. Modified simple limbal epithelial transplantation using cryopreserved amniotic membrane for unilateral limbal stem cell deficiency. American journal of ophthalmology. 2014 Sep:158(3):469-75.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.06.002. Epub 2014 Jun 14 [PubMed PMID: 24932987]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKenyon KR, Tseng SC. Limbal autograft transplantation for ocular surface disorders. Ophthalmology. 1989 May:96(5):709-22; discussion 722-3 [PubMed PMID: 2748125]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePellegrini G, Traverso CE, Franzi AT, Zingirian M, Cancedda R, De Luca M. Long-term restoration of damaged corneal surfaces with autologous cultivated corneal epithelium. Lancet (London, England). 1997 Apr 5:349(9057):990-3 [PubMed PMID: 9100626]

Kreimei M, Sorkin N, Einan-Lifshitz A, Rootman DS, Chan CC. Long-term outcomes of donor eyes after conjunctival limbal autograft and allograft harvesting. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 2019 Oct:54(5):565-569. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2018.11.003. Epub 2019 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 31564346]

Shortt AJ, Secker GA, Notara MD, Limb GA, Khaw PT, Tuft SJ, Daniels JT. Transplantation of ex vivo cultured limbal epithelial stem cells: a review of techniques and clinical results. Survey of ophthalmology. 2007 Sep-Oct:52(5):483-502 [PubMed PMID: 17719371]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAtallah MR, Palioura S, Perez VL, Amescua G. Limbal stem cell transplantation: current perspectives. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2016:10():593-602. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S83676. Epub 2016 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 27099468]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHolland EJ. Management of Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency: A Historical Perspective, Past, Present, and Future. Cornea. 2015 Oct:34 Suppl 10():S9-15. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000534. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26203759]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYin J, Jurkunas U. Limbal Stem Cell Transplantation and Complications. Seminars in ophthalmology. 2018:33(1):134-141. doi: 10.1080/08820538.2017.1353834. Epub 2017 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 29172876]

Vazirani J, Ali MH, Sharma N, Gupta N, Mittal V, Atallah M, Amescua G, Chowdhury T, Abdala-Figuerola A, Ramirez-Miranda A, Navas A, Graue-Hernández EO, Chodosh J. Autologous simple limbal epithelial transplantation for unilateral limbal stem cell deficiency: multicentre results. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2016 Oct:100(10):1416-20. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307348. Epub 2016 Jan 27 [PubMed PMID: 26817481]

Borroni D, Wowra B, Romano V, Boyadzhieva M, Ponzin D, Ferrari S, Ahmad S, Parekh M. Simple limbal epithelial transplantation: a review on current approach and future directions. Survey of ophthalmology. 2018 Nov-Dec:63(6):869-874. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2018.05.003. Epub 2018 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 29800578]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShanbhag SS,Nikpoor N,Rao Donthineni P,Singh V,Chodosh J,Basu S, Autologous limbal stem cell transplantation: a systematic review of clinical outcomes with different surgical techniques. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2020 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 31118185]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence