Continuing Education Activity

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a serious medical condition, which often results in severe morbidity and permanent disability. It occurs when the axons of nerves running through the spinal cord are disrupted, leading to loss of motor and sensory function below the level of injury. Injury is usually the result of major trauma, and primary injury is often irreversible. This activity outlines the evaluation and management of SCI and reviews the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of medical conditions and emergencies due to spinal cord injuries.

- Outline the appropriate evaluation steps for spinal cord injuries.

- Review the management options available for spinal cord injuries.

- Describe interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance the management of spinal cord injuries and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a serious medical condition, which often results in severe morbidity and permanent disability. It occurs when the axons of nerves running through the spinal cord are disrupted, leading to loss of motor and sensory function below the level of injury. Injury is usually the result of major trauma, and primary injury is often irreversible.[1] These injuries are particularly costly and disabling as they disproportionately affect patients under 30-years-old, lead to significant functional impairment for the remainder of the individual’s life, and put the individual at risk for numerous complications leading to increased morbidity and mortality.[2] SCI is estimated to have a lifetime economic impact of 2 to 4 billion dollars.[3][4]

Etiology

Within the United States, the leading cause of spinal cord injury is motor vehicle collisions, constituting 38% of new SCI each year. 30% are due to falls, 13% due to violence, 9% from sports injuries, and 5% from medical and surgical etiologies.[2]

Epidemiology

Globally, between 250,000 and 500,000 patients, each year suffer a spinal cord injury. Most of these cases are due to preventable causes such as violence and motor vehicle accidents. In the United States, there are approximately 17,000 new cases of SCI each year, and roughly 282,000 persons are estimated to be living with SCI.[2] Males represent the majority of patients with SCI related to a sports injury. The age group with the highest risk of SCI is from 16 to 30 years of age.

Pathophysiology

Spinal cord injuries are most often due to either direct trauma to the spinal cord or from compression due to fractured vertebrae or masses such as epidural hematomas or abscesses. Less commonly, the spinal cord may become injured due to compromise of blood flow, inflammatory processes, metabolic derangements, or exposure to toxins.

Primary Injury

SCI results from initial insult such as mechanical forces to it, which is known as the primary injury. The most common mechanism of primary injury is a direct impact, and persistent compression typically occurs by bony fragments through fracture-dislocation injuries. Contrary to fracture-dislocation, hyperextension injuries usually result in less frequent, impact alone plus transient compression. The third mechanism, distraction injury, a stretch and tear of the spinal cord in its axial plane, occur by pulling apart of two adjacent vertebrae. Lastly, laceration/transection injury, which arises through sharp bone fragments, severe dislocations, and missile injuries.[5]

Secondary Injury

Secondary injury is a series of biological phenomena that begins within minutes and continue to self-immolation for weeks or months following the initial primary injury. The acute phase of secondary injury begins after SCI and involves vascular damage, ionic imbalances, free-radical formation, the initial inflammatory response, and neurotransmitter accumulation (excitotoxicity). The subacute phase follows, which includes demyelination of surviving axons, Wallerian degeneration, matrix remodeling, and formation of the glial scar.[5]

Immune Response Spinal Cord Injury

Neuroinflammation can be either beneficial or detrimental following SCI, providing time-point and the state of immune cells. The first three days following SCI, inflammatory events involve recruiting blood-born neutrophils resident microglia and astrocytes to the injury site. The second phase, approximately three days post-injury, enrolls macrophages, B- and T-lymphocytes to the injury site. CD4+ helper T become activated by antigen-presenting cells and release cytokines that subsequently stimulate B cell to synthesize and release antibodies, which exacerbate neuroinflammation and subsequent tissue destruction. Neuroinflammation is more robust in the acute phase of SCI.

Ongoing inflammation may persist in subacute and chronic phases, even for the rest of a patient's life. Inflammatory cell composition and phenotype alter according to the stage of inflammation and the signals existing in the injury microenvironment. T cells, B cells, and microglia/macrophages are capable of gaining either pro-inflammatory or an anti-inflammatory pro-regenerative phenotype.[5]

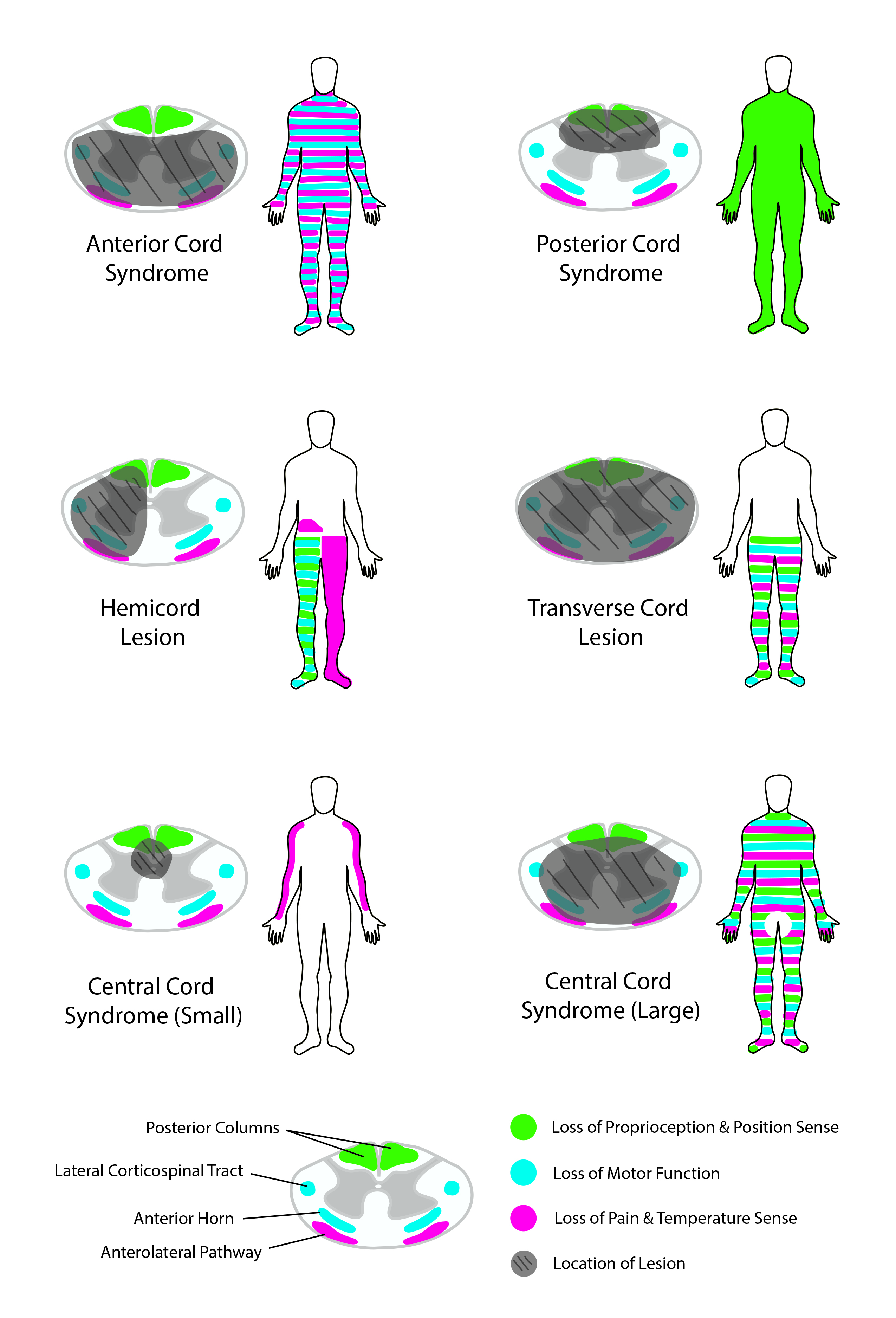

Disruption of nerve axons running through spinal cord tracts leads to loss of motor and sensory function below the level of injury. Patterns of disability are dependent on the level of the injury and which spinal tracts are affected.[6][7]

Spinothalamic tracts run within the anterior aspect of the spinal cord. These nerve axons carry sensory information for pain and temperature. Damage to these tracts leads to contralateral loss of pain and temperature sensation. Corticospinal tracts run within the lateral aspects of the spinal cord. These nerve axons control motor function. Damage to these tracts leads to ipsilateral weakness or paralysis. In the cervical spine, axons leading to the upper extremities are located close to the center of the spinal cord.

In contrast, axons leading to the lower extremities are located on the periphery. The dorsal columns run within the posterior aspect of the spinal cord. These tracts carry information for tactile, proprioceptive, and vibratory sensation. Damage to these tracts leads to contralateral loss of tactile, proprioceptive, and vibratory sensation.

History and Physical

Typically patients will present after a significant traumatic event such as a motor vehicle accident, fall from a height, or gunshot wound. Vitals are unlikely to be abnormal, although high cervical injuries can result in hypotension and bradycardia due to loss of sympathetic tone. The physical exam will reveal weakness and sensory deficits correlating to the pattern of injury, and the spinal tracts affected. Several classic patterns of injury are well described.[6][7][8]

Complete Transection of the Spinal Cord [9]

- These injuries typically demonstrate complete bilateral loss of motor function, pain sensation, temperature sensation, proprioception, vibratory sensation, and tactile sensation below the level of injury.

- Lumbosacral injuries will present with paralysis and loss of sensation in the lower extremities. These injuries may also result in loss of bowel control, loss of bladder control, and sexual dysfunction.

- Thoracic injuries lead to the same deficits as lumbosacral injuries and, in addition, may result in loss of function of the muscles of the torso, leading to difficulty maintaining posture.

- Cervical injuries lead to the same deficits as thoracic injuries and, also, may result in loss of function of the upper extremities leading to tetraplegia. Injuries above C5 may also cause respiratory compromise due to loss of innervation of the diaphragm.

Central Cord Syndrome

- This is the most common incomplete SCI.

- Injury is caused by hyperextension of the neck leading to compression of the cervical spinal cord, causing damage primarily to the center of the cord.

- This pattern of injury leads to weakness affecting the upper extremities more so than the lower extremities. This pattern occurs as the corticospinal tracts are arranged with those axons supplying the upper extremities located closer to the center of the spinal cord, while those supplying the lower extremities are closer to the periphery.

- There may also be an associated loss of pain and temperature sensation below the level of injury.

Anterior Cord Syndrome

- Classically due to compromise of blood flow from the anterior spinal artery.

- Bilateral injury to the spinothalamic tracts leads to bilateral loss of pain and temperature sensation below the level of injury.

- Bilateral injury to corticospinal tracts leads to weakness or paralysis below the level of injury.

- As dorsal columns are unaffected, tactile sensation, proprioception, and vibratory sensation remain intact.

Posterior Cord Syndrome

- This injury pattern rarely occurs due to trauma. More often, injury is due to infectious, toxic, or metabolic causes.

- Damage to dorsal columns causes loss of tactile sensation, proprioception, and vibratory sensation.

- As spinothalamic and corticospinal tracts are unaffected, there is the preservation of pain sensation, temperature sensation, and motor function.

Brown-Séquard Syndrome [10]

- Injury results from right or left-sided hemisection of the spinal cord.

- Transection of the corticospinal and dorsal column nerve tracts leads to ipsilateral loss of motor function, tactile sensation, proprioception, and vibratory sensation below the level of injury.

- Transection of the spinothalamic tract leads to contralateral loss of pain and temperature sensation below the level of injury.

Conus medullaris Syndrome

- It is caused by injury to the terminal aspect of the spinal cord, just proximal to the cauda equina.

- It characteristically presents with loss of sacral nerve root functions. Loss of Achilles tendon reflexes, bowel and bladder dysfunction, and sexual dysfunction may be observable.

Neurogenic Shock [11][1]

- It results from high cervical injuries affecting the cervical ganglia, which leads to a loss of sympathetic tone.

- Loss of sympathetic tone results in a shock state characterized by hypotension and bradycardia.

Evaluation

As spinal cord injuries most often occur in the context of significant trauma, a comprehensive physical examination and clinical assessment for concurrent injuries are necessary at the time of presentation. Recognition of the above injury patterns can help localize the location and type of injury suffered. Clinical examination with a detailed and accurate examination of motor and sensory nerves is essential for classification.

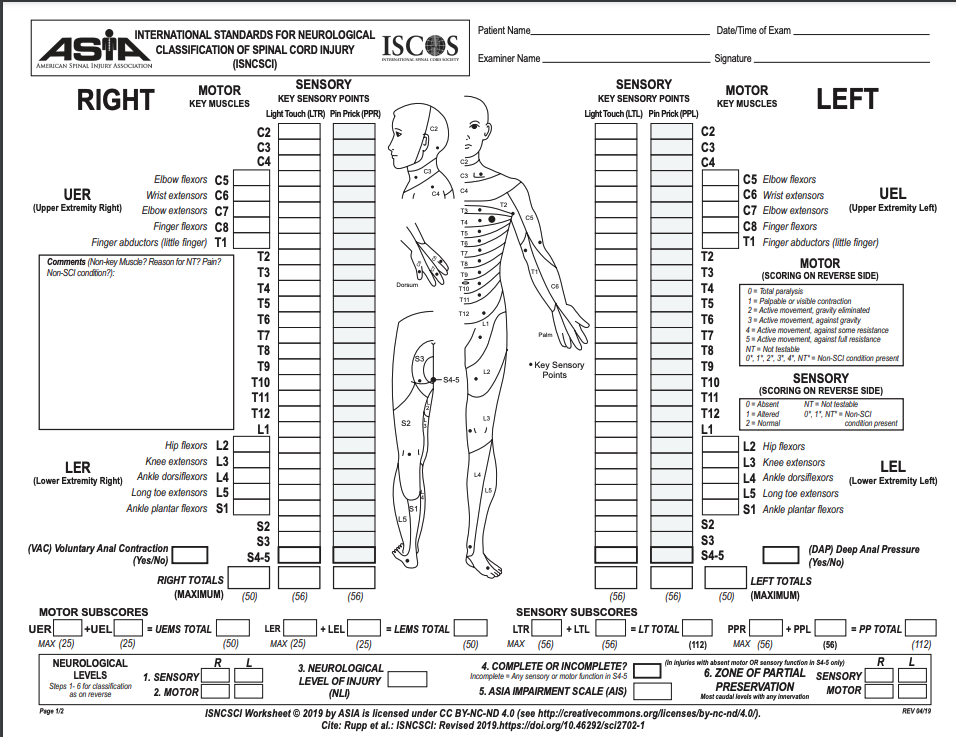

SCI is graded using the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale. The grading system varies based on the severity of injury from letters A to E.[12]

- ASIA A: Complete injury with loss of motor and sensory function.

- ASIA B: Incomplete injury with preserved sensory function, but complete loss of motor function.

- ASIA C: Incomplete injury with preserved motor function below the injury level, less than half these muscles have MRC (Medical Research Council) grade 3 strength.

- ASIA D: Incomplete injury with preserved motor function below the injury level, at least half these muscles have MRC (Medical Research Council) grade 3 strength.

- ASIA E: Normal motor and sensory examination.

Imaging is vital to identify the injuries accurately. Plain radiographs have been used traditionally, however with advancing technology and poor sensitivity with plain radiographs, computerized tomography (CT or CAT scan) has been replaced as the initial screen to identify bony abnormalities like fractures. CT can reveal vertebral fractures and raise suspicion for SCI; however, it has very poor sensitivity for soft tissue injuries. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is needed to accurately assess the level of injury to the spinal cord itself.[13][14] MRI can help with prognostication, and several clinical scores use this to predict prognosis.[15] Early spinal cord injury findings see on an MRI include spinal cord compression, spinal cord contusion, spinal cord edema, spinal cord transection, spinal cord hemorrhage, and ligamentum flavum bulging.[16] Subacute findings include spinal cord edema, subacute progressive ascending myelopathy, and syrinx.[17]

Other associated imaging findings may include:[14]

- Traumatic disc herniation: Seen with vertebral disc dislocations and hyperextension injuries. Nucleus pulpous herniation and annulus fibrosus herniation are seen in this condition.

- Epidural hematoma

- Pseudomeningoceles

- Extradural fluid collections

- Vascular injuries of arteries like the carotid artery, vertebral artery, etc.,

- Vertebral fractures

Treatment / Management

Treatment begins at the site of injury and paramedics, and emergency medical services staff can play a significant role in stabilization before transfer to the hospital. Immobilization can help prevent the worsening of any existing injuries. In the case of serious trauma, address any life threats or concurrent traumatic injuries immediately.

Hypotension and shock will worsen the impact of any existing SCI and worsen the likelihood of neurologic recovery. Immediate measures are necessary to maintain breathing and hemodynamic stability. Surgical decompression may be warranted if feasible to lessen the extent of the injury.[1][18][19] This procedure helps to stabilize the spine, to prevent pain, reduce deformity, deliver compression from a herniated disc, blood clot, or foreign body.

Patients with SCI are best managed in neurological intensive care units with expertise in managing such patients. Dedicated trauma units must be identified and designated to transfer and care for these patients.

Rehabilitation is an integral part of healing, and these patients have the best possible outcomes with intense rehabilitation therapy under the guidance of physiatrists, physical therapists, and occupational therapists. Rehabilitation is to be continued on an outpatient basis once the patient is ready for discharge from the inpatient rehabilitation unit.

Several medications have had trials to help with improving outcomes in SCI, but the results have not shown significant benefits. Trials with nimodipine, gacyclidine, thyrotropin-releasing hormone, riluzole, gangliosides, minocycline, magnesium, acidic fibroblast growth factor have been studied to see their impact on improvement in patients with SCI.[3][20][21][22][23][24][25] At the current time, further research is necessary with regards to these agents, and high dose steroids are the mainstay for acute treatment of SCI.

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of spinal cord injury will likely be relatively precise based on the patient’s presentation, which will probably be following a major traumatic event.[1] However, when the time of onset and preceding events are less clear, a broader differential for motor and sensory deficits should be considered.

Central Nervous System Pathologies

- Cerebrovascular accident (CVA)

- Postictal (Todd) paralysis

- Hemiplegic migraine

- Multiple sclerosis

Peripheral Nerve Pathologies

- Guillain-Barré syndrome

- Transverse myelitis

- Tick paralysis

Neuromuscular Junction Pathologies

- Myasthenia gravis

- Organophosphate toxicity

- Botulism

Other Pathologies

- Hypoglycemia

- Hypokalemic periodic paralysis

- Hypocalcemia

- Diabetic neuropathy

- Conversion disorder

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with spinal cord injury is very poor. Unfortunately, there is no definite treatment leading to recovery for SCI. Less than 1% of patients with SCI recover complete function before the time of hospital discharge. The level of disability suffered directly correlates to the level of injury, with higher-level injuries resulting in more significant disability and higher complication rates. Patients will SCI suffer significantly increased mortality in the first year following injury, and those that survive still have decreased life expectancy. Only 12% go on to hold employment, and less than one half will get married.[2]

Complications

Spinal cord injuries are associated with numerous complications such as urinary tract infections, pressure sores, deep vein thromboses, autonomic dysreflexia, and chronic pain.

Autonomic dysreflexia occurs in individuals with SCI at or above thoracic spinal level 6 (T6). This condition often manifests as orthostatic hypotension. The symptoms of orthostatic hypotension are often challenging to treat. Symptomatic management with abdominal binders, elastic stockings, peripheral vasoconstrictor medications like midodrine, and mineralocorticoids like fludrocortisone can help. Increased salt intake can also help with volume expansion and help with symptom control.

There are also significant indirect costs through lost mobility, inability to work, and heavy caregiver burden.[19][26]

The most common causes of mortality are pneumonia and sepsis.[2]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Spinal cord injury is very stressful and overwhelming for the patient and the families. Patient education must be an important part of the clinical management of patients with this condition. Counseling is necessary regarding prognosis, complications, and outcomes. Support groups can help with the management of issues like anxiety, frustration, loneliness, and depression. The patient should receive counsel about the diagnosis and the prognosis. Prevention centers can help with mitigating factors leading to traumatic injuries like improvement in motor vehicle safety, gun control, and social programs aimed at the prevention of violence.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Once a patient has suffered spinal cord injury, their quality of life and life expectancy is dependent upon continued well-coordinated care between an interprofessional healthcare team. A team approach is ideal for helping mitigate the many complications that can result from SCI [19][26]:

- Evaluation by a neurosurgeon at the time of injury can help minimize the extent of the initial injury.

- Nursing care can prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infections, pressure sores, and aspiration pneumonia from occurring.

- Physical and occupational therapists can help maximize the patient’s level of function.

- Social workers can coordinate disability services and reimbursements.

- A psychiatrist should be available to help the patient with depression, which is common following SCI.[27]

- Pain management specialists can help manage ongoing issues with chronic pain.