Continuing Education Activity

Pes anserine bursitis is a common cause of medial knee pain. The condition arises from inflammation of the bursa between the medial tibia and the confluence of the semitendinosus, gracilis, and sartorius tendons. Pes anserine bursitis often presents as pain in the inner aspect of the knee resulting from overuse, direct trauma, or underlying conditions such as osteoarthritis. Pes anserine bursitis has a generally favorable prognosis. However, the condition can resemble other conditions affecting the knee, such as aseptic bursitis or osteomyelitis, which can obscure the diagnosis initially.

This activity for healthcare professionals is designed to enhance the learners' competence in evaluating and managing pes anserine bursitis. This activity will improve learners' proficiency when collaborating with an interprofessional team caring for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Identify the factors predisposing individuals to pes anserine bursitis.

Evaluate a patient with medial knee pain and create a clinically appropriate diagnostic plan.

Determine a personalized treatment approach for a patient diagnosed with pes anserine bursitis.

Implement a well-coordinated, interprofessional team approach to provide effective care to patients affected by pes anserine bursitis.

Introduction

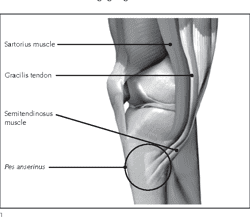

The term "pes anserinus" translates to “goose's foot” in Latin and refers to the conjoined tendons of the sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus as they insert on the anteromedial proximal tibia (see Image. Pes Anserinus Tendons).[1] The pes anserine tendons, each innervated by a distinct nerve, create a structure about 5 cm distal to the medial knee joint line. As crucial knee flexors, these muscles also aid in tibial internal rotation and provide resistance against rotational and valgus stresses.

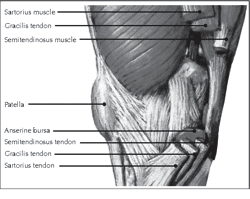

Located underneath the conjoined tendons is the pes anserinus bursa (see Image. Medial View of the Knee). This synovial tissue-lined structure facilitates smooth movement between the conjoined tendons and tibia. The bursa occasionally cushions between the conjoined tendons and medial collateral ligament (MCL). Bursal inflammation and pain can occur following an injury due to increased synovial fluid production by the bursal cells.[2]

Adjacent to the pes anserinus bursa is the musculi sartorii bursa. This fibrous structure is situated between the sartorius tendon and the combined gracilis and semitendinosus tendons.[3] The smaller musculi sartorii bursa may communicate with the pes anserine bursa, and both are commonly referred to collectively as the pes anserine bursa. These bursae do not typically communicate with the knee joint, highlighting their unique anatomical and functional significance in knee movement and pathology.

Pes anserine bursitis involves the inflammation of the bursal sac beneath the pes anserinus.[4] The condition predominantly affects women who are overweight and middle-aged. Pes anserinus bursitis is characterized by pain at the pes anserine insertion, typically triggered by activities such as stair climbing or rising from a seated position.[5]

Pes anserine bursitis is often associated with other knee disorders, especially osteoarthritis. The condition presents as non-traumatic, spontaneous inferomedial knee pain.[6] Pes anserine bursitis is generally self-limiting, usually responding effectively to conservative treatment methods like exercise and stretching programs. The term "pes anserine pain syndrome" encompasses a broader spectrum of medial knee pain, potentially including conditions beyond bursal inflammation. Differentiating between pes anserine bursitis and tendinitis can be challenging, as both the tendons and bursa lie close to each other. However, management for both conditions is the same.

Moschcowitz was the first to describe pes anserine bursitis in 1937 as a condition notable for knee pain, primarily in females, elicited by climbing stairs and rising from a seated position. Difficulty with knee flexion was also observed.

Etiology

Pes anserine bursitis is often related to repetitive stress or direct trauma to the pes anserine bursa. Tight hamstrings exert excessive pressure on the bursa, leading to mechanical and friction-based irritation. Direct trauma can aggravate the inflammation. The condition is closely associated with other knee pathologies, such as Osgood-Schlatter syndrome, suprapatellar plical irritation, and medial compartment or patellofemoral arthritis, which can induce hamstring spasms. Factors like obesity and valgus knee deformity, especially in middle-aged women, further elevate the risk.

Flat feet (pes planus) also predispose individuals to bilateral pes anserine bursitis due to abnormal lower limb alignment, resulting in more medial-sided pressure to the knee. Local trauma, bone exostosis, and tendon tightness are also contributing factors.[7][8]

Combined physiological and lifestyle factors influence pes anserine bursitis' development.[9] Mechanical knee issues, obesity, and activities requiring extensive lateral movement, such as basketball and racquet sports, are significant contributors.[10]

The condition is also common in patients with early-stage medial knee osteoarthritis and in a considerable number of patients with diabetes mellitus. Some studies suggest that the condition affects a quarter to a third of diabetics. In a study of 94 patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, 34 individuals had pes anserine bursitis. A significant gender disparity was also observed, as 91% of the affected individuals were women and 9% were men. Contrastingly, bursitis was not observed in any control subjects without diabetes.

Epidemiology

Pes anserine bursitis is prevalent among obese middle-aged women, particularly those with knee osteoarthritis. Female-specific anatomical differences like a broader pelvis and greater knee valgus angulation increase stress on the pes anserinus insertion point. However, the incidence and frequency of pes anserine bursitis in the general population is difficult to pinpoint largely due to its symptoms often mirroring other knee pathologies.[11] Pes anserine bursitis' actual prevalence is challenging to determine, as the condition is frequently misclassified as anterior knee pain or patellofemoral syndrome and is thus likely underreported.[12]

Recent research has shed light on pes anserine bursitis' relation to knee osteoarthritis. Uysal et al found that 20% of patients with primary knee osteoarthritis had concomitant pes anserine bursitis. A direct correlation was also observed between the severity of osteoarthritis and bursitis size.

Similarly, Kim et al research showed that pes anserine bursitis was significantly more prevalent in individuals with knee osteoarthritis (17.5%) than those without (2.2%). In the same group, pes anserine bursitis was more prevalent among individuals experiencing knee pain (14.4%) than those without pain (2.5%).[13]

However, diagnostic imaging and healthcare data analysis do not correlate with these findings.[14] A review of 509 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of symptomatic adult knees detected pes anserine bursitis in only 2.5% of cases. Meanwhile, a separate study within the United States Military Health System diagnosed the condition in only 1.4% of 127,570 patients with nonspecific knee complaints over 2 years.[15] The discrepancies in the above studies underscore not only the condition's presence but also the diagnostic and documentation challenges it poses.[16][17]

Pathophysiology

Pes anserine bursal inflammation typically arises from pre-existing knee disorders, particularly osteoarthritis. Mechanical stress initiates tissue injury, exacerbated by activities like ascending or descending stairs. The sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus muscles—vital to knee flexion and internal tibial rotation—protect against rotary and valgus stresses. Medial knee joint disruptions, including medial meniscus or MCL changes, can lead to localized inflammation of these tendinous structures that may extend to the anserine bursa.[18][19]

Pathological studies have yet to conclusively pinpoint whether the symptoms primarily result from bursitis, tendinitis, or fasciitis in this area. Panniculitis has also been noted, especially in obese patients. Additionally, pes anserine bursitis or tendinitis can be difficult to diagnose even with clear symptoms, as imaging techniques like ultrasonography and MRI often do not reveal any pathologic changes.[20]

History and Physical

History

Patients who are ultimately diagnosed with pes anserine bursitis are typically middle-aged females with a risk factor for the condition, such as knee osteoarthritis, obesity, frequent sports activities, and valgus knee. Severe, stabbing pain suddenly occurs on the medial knee aspect. Activities that precipitate or worsen the pain include rising from a seated position, using the stairs, or sitting with crossed legs. Trauma is not always reported, though it can aggravate the symptoms. The pain can persist, with mild erythema and edema developing within hours to days. However, pain can also subside spontaneously and become recurrent for months before presentation.

Sports activities predisposing individuals to pes anserine bursitis include running and others requiring lateral movements and sudden directional changes like basketball, soccer, and racket sports. "Breaststroker's knee" among swimmers also presents with medial knee pain. The condition is often related to MCL strains but may also be due to pes anserine bursa pathology. Note, pes anserine bursitis coexisting with an MCL injury is not uncommon.

Physical Examination

The physical examination of pes anserine bursitis focuses on identifying pain and tenderness in the inner and medial aspects of the knee joint, particularly when the knee is fully extended. Tenderness is characteristically elicited over the proximal medial tibia, approximately 5 to 7 cm below the anteromedial joint margin. This location is the insertion point of the pes anserine group's conjoined tendons. The pes anserine bursa is situated deep to these tendons, palpable if effusion and thickening are present. Crepitus indicative of bursitis may also be detected. Muscle weakness and a reduced range of motion may be observed, though pain often influences these findings.

The condition may also manifest as posteromedial or midline knee pain similar to meniscal lesions. Increased tenderness radiating proximally into the thigh, most noticeable upon flexing the knee to 90°, could indicate concurrent hamstring tendinitis.

Differentiating pes anserine bursitis from other pathologies

Palpation is crucial for patients complaining of medial knee pain to distinguish between joint-line and pes anserine bursal pathology, which can coexist. For example, pain along the medial joint line may indicate a meniscal tear, though this condition may also be asymptomatic. Pes anserine bursal tenderness with a concomitant asymptomatic meniscal tear is common, necessitating comparison with the contralateral knee. Meanwhile, valgus stress in athletes may produce an MCL injury. Tenderness is typically located superoposterior to the pes anserine bursa.

Additional assessments and considerations

The hamstring-popliteal angle should be assessed for underlying hamstring tightness, measured by flexing the patient’s hip to 90° and then extending the leg. A flexion angle greater than 15° to 20° indicates hamstring tightness, which exacerbates the bursal inflammation. Other causes of pain in this location include bony exostosis of the tibia, saphenous nerve compression by the inflamed bursa, and tibial stress fracture.[21]

In sports-related cases, symptoms may be elicited through resisted internal rotation and flexion of the knee. Meanwhile, chronic cases in older adults do not typically present with flexion- or extension-induced pain and bursal swelling.

Evaluation

Pes anserine bursitis is diagnosed clinically, often without the need for extensive additional workup. Nevertheless, various diagnostic tools may be employed in complex or atypical cases. Plain knee radiographs are usually obtained to look for underlying bony abnormalities, including osteoarthritis.[22]

Pes Anserine Bursal Injection

A diagnostic or therapeutic injection into the bursa can be instrumental in cases of suspected chronic pes anserine bursitis. Lidocaine, with or without a corticosteroid, is the agent often used. The procedure alleviates the symptoms, thus confirming the diagnosis. The bursal injection also helps assess the condition's contribution to the patient's knee problems.

Imaging Techniques

The preferred imaging modalities for evaluating the area of the pes anserine bursa are radiography, ultrasonography, and MRI. The choice of imaging study depends on various factors, including the availability of resources, severity of symptoms, and specific clinical scenarios.

Radiography typically includes standing anteroposterior and lateral views to rule out bony abnormalities like proximal tibial stress fractures, arthritis, osteochondroma, exostosis, or osteochondritis dissecans lesions. These conditions may tighten the hamstring muscles and produce bursal inflammation.

Ultrasonography is useful for locating large cystic bursal swellings and distinguishing them from other causes of medial proximal tibial swelling, such as joint effusions. However, ultrasound findings are often nonspecific in suspected cases of pes anserine bursitis.[23]

MRI is useful for differentiating pes anserine bursitis from intraarticular pathologies. Increased signal intensity and fluid formation around the pes anserine bursa are characteristic. However, fluid-filled anserine bursae are also found in asymptomatic knees. Thus, MRI findings alone cannot confirm the diagnosis. Axial images are especially helpful for distinguishing fluid in the pes anserine bursa from other medial fluid collections.[24][25][26]

Laboratory, Aspiration Studies, and Biopsy

These tests may be obtained to rule out more serious conditions, such as an infection or tumor, especially in immunocompromised persons. The decision to perform these additional tests is individualized and depends on the patient's medical history, physical examination findings, and initial imaging results.

If the initial clinical and imaging findings suggest a possible infection, the recommended next steps are erythrocyte sedimentation rate, complete blood count with differential, and C-reactive protein level. Aspiration with fluid analysis is rarely performed but can show mononuclear cells or the absence of inflammatory cells and crystals. This diagnostic procedure is particularly relevant in examining immunocompromised patients presenting with localized warmth, pain, and swelling.[27][28] A biopsy is indicated if malignancy is suspected.

Treatment / Management

Pes anserine bursitis is primarily a self-resolving condition for which conservative management usually suffices. Most patients experience successful outcomes with noninvasive measures, including outpatient physical therapy. Such therapy often focuses on a regular stretching regimen, especially for the hamstring tendons. These exercises also serve as injury-preventive measures for athletes. More advanced treatments are considered when symptoms fail to resolve even after optimizing conservative treatments like rest, ice, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, and physical therapy.

Conservative Measures

Initial therapy typically includes rest, ice, and short-term NSAID use unless contraindicated. Rest is crucial and typically entails reducing or avoiding activities that exacerbate symptoms.

Physical therapy is a crucial component of conservative management. This modality focuses on stretching and strengthening key muscle groups, including the adductors, abductors, quadriceps, and hamstrings. Special attention is given to enhancing the last 30° of knee extension, an action mostly attributed to the vastus medialis.

Addressing concomitant conditions like osteoarthritis, knee malalignment, obesity, and pes planus is crucial in minimizing the risk of pes anserine bursitis recurrence. Lifestyle modifications, weight management, and corrective orthopedic measures can improve outcomes.[29]

Advanced Therapies

Treatments such as ultrasound, electrical stimulation, extracorporeal shock wave therapy, and kinesiotaping are employed in refractory cases.[30][31] Ultrasound is reportedly effective in reducing inflammation, while extracorporeal shock wave therapy has shown promise in reducing pain in various studies. Kinesiotaping has also been found to be more effective in reducing pain and swelling compared to NSAIDs or physical therapy alone.

Pharmacological and Injection Therapy

Intrabursal injection of local anesthetics, corticosteroids, or a combination of both may be considered for more persistent or severe cases.[32] Ultrasound-guided injection of these agents can provide significant pain relief. However, steroid injections risk complications like subcutaneous tissue atrophy, skin pigmentation, and tendon rupture. Autologous platelet-rich plasma injections have also proven effective in relieving pain caused by this condition. However, injections should be limited to no more than 3 yearly.[33]

Surgical Intervention

Surgery is rarely indicated in pes anserine bursitis management and is reserved for protracted, refractory cases. Bursal incision and drainage can relieve the symptoms, but literature has also reported the use of bursal excision. Underlying conditions should be addressed. For example, bony exostosis must be excised. Postsurgical care involves immobilization and a gradual return to activities.

Special Considerations for Athletes

Athletes may need to modify their activities and use protective padding over the affected area. A gradual return to play may be advised based on symptom resolution, though restrictions may be necessary in severe cases.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for pes anserine bursitis can be extensive and is crucial for accurate diagnosis and treatment. The conditions can be categorized based on their likelihood and prevalence.

More Likely

- Medial meniscus injury: presents with medial joint-line tenderness, knee locking, or catching; physical examination findings include a positive McMurray test with valgus stress and external tibial rotation.

- MCL Injury: differentiated by a history of trauma and stress maneuvers, often requiring MRI for confirmation.

- Other knee bursitis: includes inflammation of the suprapatellar, prepatellar, infrapatellar, and MCL bursae, distinguishable by location and specific pain points.

- Proximal tibial stress fracture: has a similar pain location but is more often precipitated by trauma or repetitive sports activity.

- Saphenous nerve compression: causes pain and paresthesia radiating distally; Tinel sign may be positive on physical examination

Less Likely, But Possible

- Spontaneous osteonecrosis: severe, constant medial compartment knee pain; distinguishable from pes anserine bursitis via MRI.

- Hamstring or semimembranosus tendinitis: characterized by swelling and tenderness on resisted flexion or valgus strain and often radiates proximally into the muscle belly or ischial insertion.

- L3 to L4 radiculopathy: associated with lumbar pain that radiates distally; lacks tenderness on pes anserine bursa palpation.

- Gout and pseudogout: inflammatory arthropathies affecting the knee, discernible via clinical presentation (ie, knee effusion, decreased ability to bear weight, and reduced knee range of motion) and lab tests.

Rare or Unusual Conditions

- Knee cysts: include Baker’s, meniscal, and ganglion cysts; identified by their specific locations and symptoms.

- Tumors: include benign and malignant neoplasms, such as villonodular synovitis, osteochondromatosis, synovial sarcoma, lipoma, hemangioma, and giant cell tumor.

- Vascular issues: include popliteal vein varicosity, aneurysm, or secular dilation, often consequent to trauma.

- Fibromyalgia: presents with symmetric and bilateral pain, often in overweight patients.

- Miscellaneous conditions: include Osgood-Schlatter disease, patellar tendinitis, synovial plica, patellofemoral syndrome, and others; each of these conditions has unique clinical features.

The conditions above present with specific symptoms and signs. A detailed clinical examination and appropriate diagnostic studies are essential when differentiating these conditions from pes anserine bursitis.[34][35][36]

Prognosis

Pes anserine bursitis is generally self-limiting, mostly resolving with nonoperative management. Surgical intervention is seldom needed. The long-term prognosis for this condition is favorable, particularly when exacerbating factors like joint overuse are avoided. Symptom duration can vary, influenced by underlying conditions like osteoarthritis, obesity, and deconditioning. Prompt identification and appropriate treatment of concomitant arthritic diseases significantly reduce pain and enhance overall function.

Pes anserine bursitis rarely leads to long-term consequences among athletes, even if they continue to engage in sports activities. A structured 6- to 8-week program focusing on posterior-chain stretching and strengthening exercises can effectively alleviate symptoms and allow athletes to return to their sport.[37]

Complications

Pes anserine bursitis itself rarely progresses, as it is generally a self-limiting condition. However, a chronically inflamed, painful pes anserine bursa may cause altered gait mechanics or decreased activity levels, resulting in disuse atrophy of the muscles stabilizing the knee joint.[38]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Primary preventive measures for pes anserine bursitis focus on minimizing the risk factors for its development. These measures include the following:

- Maintaining a healthy weight

- Exercising smartly

- Proper stretching and warmup before starting any physical activity

- Correcting biomechanical issues

- Choosing the appropriate footwear

- Gradual progression of exercise intensity

- Maintaining the proper posture

- Staying hydrated

As for secondary prevention, patient education is crucial in managing pes anserine bursitis. Reinjury avoidance and guidelines for a safe return to athletic activities must be emphasized. Key aspects include the following:

- Training with proper form

- Engaging in hamstring stretching and quadriceps strengthening exercises

- Choosing the appropriate footwear based on activity level and intensity

- Maintaining a healthy body weight

The importance of rest in the acute stages must also be stressed. Home-tailored physical therapy is essential for preventing disuse atrophy, especially in older individuals with arthritis. In athletic settings, patients, trainers, and coaches must be informed about gradually increasing activity level and duration. Importantly, prevention is multifaceted, and combining the above measures is often more effective than focusing on a single factor.

Pearls and Other Issues

The key points to remember when evaluating and managing pes anserine bursitis are the following:

- Pes anserine bursitis involves inflammation of the bursa located between the muscular tendons of the sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus and their insertion at the proximal medial tibia.

- The 3 muscles near the pes anserine bursa primarily flex and internally rotate the knee, movements involved when sitting cross-legged. Similar movements of the same muscle group may exacerbate the symptoms of the condition.

- Underlying osteoarthritis, obesity, and female gender are risk factors for developing this syndrome.

- The diagnosis is made clinically. Imaging is not required for diagnosis.

- Treatment of pes anserine bursitis is generally supportive, with steroid injections reserved for refractory cases. Surgery is rarely indicated.

- Addressing the underlying factors can prevent reinjury.

Treatment plans should be individualized based on the patient's specific presentation, risk factors, and response to initial interventions.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with pes anserine bursitis may be seen in all practice settings, from outpatient offices to urgent care centers and emergency departments. However, referral to an orthopedic specialist is often unnecessary unless the patient has another condition warranting further investigation and aggressive treatment. Therefore, the interprofessional team may comprise of the following:

- Primary care or emergency physician: crucial in the initial evaluation and diagnosis of pes anserine bursitis. These providers may prescribe medications for pain and inflammation and make key decisions on the need for further diagnostic tests or referrals.

- Physician assistant or nurse practitioner: may also perform initial assessments and treatments and make referrals as needed.

- Nurse: vital to patient education, medication management, and care coordination. These professionals ensure patients understand their treatment plans and follow up on appointments and recommendations.

- Physical therapist: specializes in rehabilitation and designs specific exercises for strengthening the muscles around the knee, improving flexibility, and addressing biomechanical issues. These professionals play a crucial role in the conservative management of the condition and prevention of recurrence.

Effective communication and collaboration among these healthcare professionals ensure that the patient receives comprehensive care to achieve the best outcomes.