Continuing Education Activity

Pelvic fractures may be caused by damage to the pelvic ring's components, including the hip bones, sacrum, and coccyx. Pelvic fractures often result from high-impact trauma and are frequently accompanied by additional injuries elsewhere in the body. Early stable fixation reduces blood transfusion requirements, systemic complications, and hospital stay durations and enhances overall survival. Computed tomography scans help assess pelvic anatomic integrity and detect bleeding.

This activity emphasizes the significance of avoiding excessive pelvic movement and establishing large-bore intravenous access for pain management and fluid and inotropic administration. The activity also introduces the Young-Burgess classification system, which provides participants with a comprehensive understanding of pelvic ring injuries. This classification system aids trauma and emergency physicians in tailoring initial treatments and conveying vital information to orthopedic surgeons managing these complex cases. Additionally, the activity discusses the common vascular, neurologic, and visceral injuries associated with pelvic fractures, emphasizing the need for meticulous evaluation to rule out potentially severe complications. Participants learn about corona mortis, an anastomosis that can lead to substantial blood loss within the pelvis if damaged. Potential injuries like this highlight the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in the comprehensive care of patients with pelvic fractures.

Objectives:

Develop a deep understanding of pelvic ring anatomy.

Determine a clinically appropriate diagnostic approach for evaluating a patient presenting with a potential pelvic fracture.

Implement evidence-based management strategies for patients with a pelvic fracture.

Develop interprofessional communication protocols when caring for patients with pelvic fractures, especially when creating short- and long-term management plans to improve outcomes.

Introduction

The pelvis is naturally designed to be a highly stable structure. Pelvic ring fractures occur most commonly in the setting of a high-impact trauma and are often associated with additional fractures or injuries elsewhere in the body.[1][2][3] Certain pelvic fractures do not disrupt the pelvic ring, eg, iliac wing fractures, and can typically be managed without operative intervention. Similarly, acetabulum fractures frequently occur, particularly in high-energy traumas, hip dislocations, and falls in older adults. These injuries are studied in detail and classified by the fracture's anatomy.

The Young-Burgess classification is a valuable evaluation tool when diagnosing pelvic ring injuries. By correctly assessing a pelvic ring injury, trauma surgeons and emergency physicians can provide adequate initial treatment and convey important information about the injured structures' anatomy to the orthopedic surgeon managing the condition.[4]

To appropriately apply the Young-Burgess classification system of pelvic ring injuries, clinicians must understand pelvic ligamentous anatomy. The bony pelvis is comprised of the ilium, ischium, and pubis. These structures form an anatomic ring with the sacrum. The symphyseal ligaments stabilize the pubic symphysis on the anterior side. The pelvic floor ligaments and posterior sacroiliac complex stabilize the pelvic ring on the posterior aspect. The sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments of the pelvic floor, anterior to the sacroiliac joint, resist both shear and external rotation through the sacroiliac joint. The posterior sacroiliac complex is the most posterior ligament in the pelvic ring and the most essential structure for pelvic ring stability. Injury to the posterior ligaments reveals a very high-energy injury mechanism.[5]

Pelvic ring injuries are usually accompanied by severe soft tissue disruption. Thus, vascular, neurologic, and visceral injuries are common and must be ruled out. The posterior pelvis' venous plexus accounts for most hemorrhage associated with pelvic ring injuries. The corona mortis is an anastomosis between the external iliac and obturator artery, a branch of the internal iliac artery. Intraoperative corona mortis damage can quickly result in a bad outcome due to excessive blood loss within the pelvis.[6]

Etiology

High-impact trauma from motor vehicle accidents or falls from significant heights causes most pelvic ring fractures. However, these injuries can also arise from low-impact trauma, as happens during athletic activities and falls when ambulating.[7][8][9]

Epidemiology

In the United States, pelvic fractures are estimated to occur in 37 out of 100,000 individuals per year. The incidence is highest in patients aged 15 to 28. Men younger than 35 and women older than 35 are most commonly affected.[10]

Pathophysiology

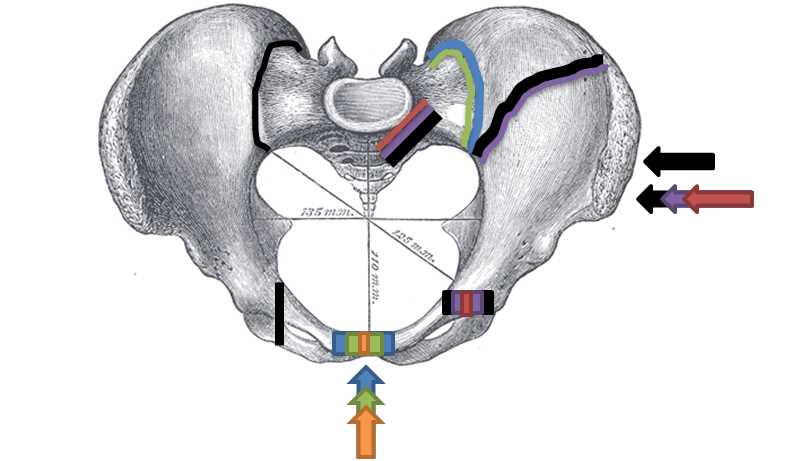

Pelvic ring injuries usually require a high-magnitude force and are thus frequently accompanied by extrapelvic injuries.[11][12] The Young-Burgess classification distinguishes various pelvic ring injuries based on the applied force's direction.[13] Orthopedic trauma surgeons frequently use this system for evaluating pelvic ring injuries and determining initial interventions. The 3 injury mechanisms described by the Young-Burgess classification are anterior-to-posterior compression (APC), lateral compression, and vertical shear injuries (see Image. Pelvic Fracture Types).

Anterior-to-Posterior Compression Injuries

The anterior pelvic ligaments collapse before their posterior counterparts in an APC injury. The symphyseal ligaments are first to sustain damage, followed by the pelvic floor ligaments (sacrospinous and sacrotuberous). The last to be injured is the posterior sacroiliac complex. APC injuries may cause pelvic ring widening without producing fractures. The progression of this injury pattern divides APC pelvic ring injuries into 3 types:

- An APC type I injury disrupts the symphyseal ligaments only and is typically caused by isolated symphyseal ligament trauma.

- An APC type II injury disrupts the symphyseal and pelvic floor ligaments, manifesting on radiographs as symphyseal ligament widening by more than 2.5 cm.

- An APC type III injury damages the anterior and posterior sacroiliac ligaments, including the posterior sacroiliac complex. APC type III injuries have the highest blood loss, transfusion requirement, and mortality rate.[14]

Lateral Compression Injuries

Lateral compression injuries are more likely to be accompanied by pelvic fractures than APC injuries. Classically, coronal-plane ramus fractures are observed in lateral compression injuries. In contrast, vertical fractures may be seen in APC injuries but less frequently, depending on the impact magnitude. Sacral ala or iliac wing fractures typically accompany these ramus fractures.[15] The most common cause of death in patients with lateral compression fractures is a closed head injury.[16][17] Lateral compression injuries are classified as follows:

- A lateral compression type I injury presents as ramus fractures with ipsilateral sacral ala fractures resulting from lateral trauma over the posterior pelvic aspect.

- A lateral compression type II injury results from lateral compression trauma with a more anteriorly directed force than a lateral compression type I injury. This condition typically presents as ramus fractures with ipsilateral crescent iliac fractures.

- A lateral compression type III injury is colloquially described as a "windswept pelvis." An unusually high-magnitude force is typically required to produce this injury. The condition presents as an ipsilateral lateral compression type I or II injury with a contralateral external rotatory component resembling an APC injury.

Vertical Shear Injuries

Vertical shear injuries result from an axial load to a hemipelvis. These injuries are more commonly seen in cases of falls from significant heights or motorcycle collisions where one leg is more likely to be forcefully loaded than the other. The iliac wing is driven cranially relative to the sacrum, disrupting the symphyseal ligaments, pelvic floor, and posterior sacroiliac complex.

History and Physical

Pelvic injuries signify a high-energy injury mechanism. A thorough trauma evaluation is necessary. All patients should undergo routine assessment as described by the American College of Surgeons (eg, the Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol), including evaluation for any potentially life-threatening condition.

Patients with pelvic injuries are at high risk for polytrauma. Airway, breathing, circulation, disability, and exposure must be assessed during the primary survey. Unconsciousness, breathlessness, and pulselessness are signs of cardiorespiratory arrest, warranting immediate resuscitation. A more detailed investigation may be pursued once the patient is stable.

Pelvic ring fractures are commonly associated with axial or appendicular spine injuries. Therefore, the spine and extremities should be examined while assessing for limb length discrepancies and angular or rotational deformities. Neurovascular structures crossing the pelvis may also be involved, and a thorough neurological examination is vital for appropriate management and monitoring.

Medical practitioners should carefully monitor the hemodynamic status of patients with pelvic fractures, as concomitant blood loss is frequent, even in cases involving closed fractures. Intraabdominal bleeding is present in up to 40% of cases, which may be accompanied by intrathoracic, retroperitoneal, or compartmental bleeding. Intrapelvic bleeding usually arises from pelvic venous plexus shearing, which can lead to hematomas holding up to 4L of blood. Posterior pelvic fractures may also injure the superior gluteal artery, constituting a surgical emergency.

Soft-tissue injury assessment may provide further insight into the degree of impact the patient sustained. The presence of perineal lacerations (eg, rectum or vagina) indicates a severe injury, including fractures potentially contaminated by urine, stool, or environmental contaminants like soil.

Neurologic injuries associated with pelvic fractures typically involve the L5 or S1 nerve roots. A sacral fracture may produce S2 to S5 sacral nerve root injury and consequent bowel, bladder, and sexual dysfunction.

Evaluation

Computed tomography (CT) scans of the abdomen and pelvis offer excellent visualization of pelvic anatomy and facilitate the assessment of potential bleeding within the pelvis, retroperitoneal space, or intraperitoneal cavity. This modality can also confirm hip dislocation and determine the presence of an associated acetabular fracture.[18][19]

The best screening test for a pelvic fracture is an anteroposterior (AP) pelvic radiograph. This study can show most pelvic fractures. Trauma patients typically undergo routine abdomen and pelvis CT scans. However, AP pelvic radiographs are rapid diagnostic tools that may be used on hemodynamically unstable patients who require fast intervention. The pelvis should also be examined as part of the Focus Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (FAST) examination, which can help identify possible causes of hypovolemic shock, such as intraperitoneal bleeding.

Retrograde urethrography is indicated for patients suspected of having a urethral tear. These patients may be men presenting with blood at the urethral meatus or women in whom Foley catheterization cannot be performed or are found to have vaginal tears or palpable fragments near the urethra. Individuals presenting with hematuria despite having an intact urethra should undergo cystography to determine the presence of a urinary bladder injury.

Pelvic angiography may be performed if a patient develops persistent hemorrhage despite adequate intravenous (IV) fluid resuscitation and pelvic stabilization. This modality may detect occult or apparent injuries, allow for embolization of any damaged arteries, and improve visualization before manipulative reduction.

Magnetic resonance imaging has been reported to have higher diagnostic accuracy than CT to evaluate pelvic fragility fractures. Dual Energy Computed Tomography (DECT) is a promising imaging modality theorized to have better sensitivity than traditional CT for pelvic fractures in older patients.[20]

Treatment / Management

Polytrauma is highly likely in patients with pelvic fractures. Any acute life-threatening traumatic injuries should be managed using the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocol.[21] Resuscitation must be initiated immediately in patients showing signs of cardiorespiratory instability.

The primary treatment goal in patients with pelvic injuries is to provide early stable fixation to minimize blood transfusion requirements, systemic complications, and hospital stays and improve survival. Excessive pelvic movement should be avoided. Large-bore IV access should be obtained immediately for fluid, inotrope, and analgesic administration. Cardiac function, oxygenation, and vital signs should be monitored closely.[22][23][24]

Mechanical stabilization with an external compression device, such as a pelvic binder or sheet centered over the greater trochanter, can help stabilize the pelvic ring and stop venous plexus hemorrhage in APC injuries. However, this intervention should be avoided in lateral compression injuries with an internal rotation component. Conversely, skeletal traction is the appropriate stabilization for a vertical shear pelvic ring injury. External pelvic fixation may be considered in a hemodynamically unstable patient. This intervention can be performed in conjunction with an emergent laparotomy.

Pelvic implant advancements, modern anesthetic techniques and intraoperative imaging, coordinated polytrauma care, and a deeper understanding of injury patterns have led to a shift toward increased operative management of previously nonoperatively treated pelvic fractures. This shift has resulted in the early repair of significant pelvic defects, early mobilization, and improved clinical outcomes.

Nonsurgical pelvic fracture treatments are appropriate for some pelvic ring injuries. For example, APC and lateral compression type I fractures can remain weight-bearing as tolerated, with early mobilization encouraged. Minimally displaced pelvic fractures may be treated nonoperatively but must be evaluated on a case-to-case basis.

Nonoperative management was previously considered the standard of care in almost all pelvic avulsion fracture cases, including anterior inferior spine avulsion fractures. However, such displaced injuries were recently found to produce late extraarticular femoroacetabular impingement. Three-dimensional (3D) damage assessment can aid in accurately determining fragment position and guide management when deciding between nonoperative and operative approaches.

The primary aim in polytrauma patients is to secure vital functions with bleeding control and avoid detrimental posttraumatic immune responses. The concept of "damage-control surgery" includes minimally invasive and rapid hemorrhage control with early stabilization of relevant unstable fractures. This intervention helps avoid a 'second hit' of the immune response, the first hit being the trauma itself.

In combined pelvic, spinal, and limb fractures, unstable spinal injuries with neurological deficits should be managed as soon as possible with decompression and internal fixation. This procedure may be performed along with pelvic injury management. In the presence of extremity injuries, open fractures, dislocations, vascular injuries, and compartment syndrome should be managed urgently. External fixation is preferred over primary definitive osteosynthesis.

Open pelvic fractures have a mortality rate of around 50%. These injuries require aggressive resuscitation with bleeding control, sepsis prevention by early surgical management, diagnosis of other injuries, and definitive bony fixation. Some measures to improve patient outcomes include considering fecal diversion, avoiding primary wound closure, and coordinating care amongst surgical teams. Fracture mapping and 3D printing are new complex pelvic fracture management advances with the potential for future clinical applications.[25]

Differential Diagnosis

Pelvic fractures may encompass several fracture types, including acetabular and iliac wing fractures. Iliac wing injuries may be managed nonoperatively. However, acetabular fractures warrant a separate investigation. Acetabular fractures are generally classified into 10 patterns, outlined by the Letournel Classification. Acetabulum fracture treatment may be nonoperative with protected weight-bearing for high-risk patients or minimally displaced fractures. Open reduction and internal fixation are indicated for acute acetabular fractures with significant displacement or hip instability.[26]

Prognosis

Patients report a significantly lower quality of life both mentally and physically 2 years after pelvic fracture treatment, even when good radiographic healing is present.[27] Pelvic fractures are highly associated with concomitant injuries. Any injury in a polytraumatic case may cause disability and compromise quality of life.

Patients with concomitant orthopedic injuries report worse disability and significantly poorer psychological, social, and occupational outcomes. Since pelvic fractures can affect sexual function, concerns were raised regarding their effects on live births and female fertility. However, a recent systematic review reported that pelvic fractures are not associated with a decrease in live births or infertility.[28]

Complications

Patients with pelvic ring injuries commonly complain of dysfunctions long after the traumatic event causing the injury. Dyspareunia has been reported in 56% of women as a symphyseal displacement of 5 mm or more can cause pain during intercourse.[29] Furthermore, women with a history of pelvic ring injuries are more likely to require a cesarean section than others.[30] Men also report sexual side effects, with up to 61% of patients reporting some sexual dysfunction. Erectile dysfunction has been reported in 19%, with rates increasing to 90% when including APC injuries.[31][32] Evidence suggesting that fixation of unstable pelvis fractures minimizes trauma-related sexual dysfunction or neurological injury is currently lacking.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Primary preventive measures for pelvic injuries primarily focus on reducing the risk of trauma and promoting bone health to prevent fractures, such as the following:

- Fall prevention and risk assessment in older individuals

- Exercise and physical therapy to improve bone density and muscle strength

- Ensuring adequate calcium and vitamin D intake

- Following safety guidelines at work or in sports

- Proper movement techniques when engaging in physical activities

- Home environmental modifications to reduce trauma risk

- Avoiding risky behavior predisposing to hip injuries

For secondary prevention, patients with pelvic ring injuries should be counseled on the long-term sequelae associated with pelvic ring injuries, especially if accompanied by injuries in other sites. Many patients endure permanent disability, which can have financial, mental, and physical tolls. The support of an interdisciplinary team is necessary to help patients rehabilitate and address their disabilities appropriately.[28]

Pearls and Other Issues

The most important points to remember when evaluating and managing pelvic injuries include the following:

- Pelvic fractures are usually the result of high-impact trauma. Polytrauma is thus frequent and may result in hemodynamic instability. However, pelvic fractures must also be ruled out in low-impact trauma cases.

- The initial management should follow ATLS protocols.

- Pelvic stabilization prevents further hemorrhage and improves outcomes in patients with pelvic trauma.

- CT allows good visualization of the pelvic structures. However, pelvic x-rays and ultrasonography can help detect abdominopelvic injuries quickly.

- Nonoperative management may be considered for low-grade pelvic ring fractures. Meanwhile, early surgery in high-grade pelvic ring fractures improves outcomes.

- An interprofessional approach optimizes the management of pelvic injuries.

- Early mobilization and rehabilitation minimize complications and improve functional outcomes in patients recovering from pelvic trauma.

- Pelvic trauma and associated injuries can have physical, financial, and psychological impacts on the patient, compromising quality of life in the long term.

Close monitoring for potential complications such as neurovascular injury, visceral damage, infection, and thromboembolism is necessary throughout the patient's hospitalization and recovery period.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Collaboration between healthcare professionals from various disciplines allows for prompt evaluation and management. An interprofessional approach thus improves outcomes for patients with pelvic fractures.

Emergency medicine services stabilize patients in the prehospital setting and transport them quickly to the nearest appropriate facility. Emergency medicine physicians provide initial assessment, stabilization, and resuscitation of patients with pelvic trauma in the emergency department. Trauma surgeons specialize in evaluating and managing traumatic injuries and lead the overall care of patients with pelvic trauma, performing surgical interventions when necessary. Orthopedic surgeons may be involved in managing pelvic fractures and treating other musculoskeletal injuries.

Interventional radiologists may perform minimally invasive procedures, such as pelvic angiography and embolization, to control bleeding in patients with pelvic trauma. Anesthesiologists provide perioperative care, including anesthesia management, pain control, and hemodynamic monitoring during surgical procedures for pelvic trauma. Urologists and gynecologists may be involved when sexual dysfunction ensues. Urologists may also manage bladder dysfunction if present.

Nurses are involved in patient monitoring, administering medications, assisting with procedures, and offering support and education to patients and their families throughout their hospitalization. Occupational therapists assist patients with pelvic trauma in regaining functional independence and adapting to any physical limitations resulting from their injuries. Physical therapists are involved in the rehabilitation of patients with pelvic trauma, helping to restore mobility, strength, and function through tailored exercise programs and interventions. Pharmacists regulate and assist with pain relief.

Mental health professionals provide psychological and emotional support to patients who develop psychological complications postinjury. Social workers provide counseling, psychosocial support, and assistance with discharge planning, including coordinating postdischarge care and support services for patients and their families.

By working collaboratively as an interprofessional team, healthcare professionals can provide comprehensive, patient-centered care to optimize outcomes for individuals with pelvic trauma. This approach ensures that patients receive timely interventions, holistic support, and coordinated care throughout their treatment and recovery journey.[33][34]