Continuing Education Activity

Brain abscess is a localized zone of necrosis with a surrounding membrane within the brain parenchyma, usually resulting from an infectious or traumatic process. The most frequent microbial pathogens isolated from brain abscesses are Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. This activity explains the risk factors, evaluation, and management of brain abscesses and highlights the importance of the interprofessional team in enhancing care for affected patients.

Objectives:

- Describe the clinical presentation of patients with brain abscesses.

- Outline the evaluation of patients with brain abscesses.

- Explain the treatment strategies for brain abscesses.

- Review interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance the evaluation and management of brain abscesses and optimize outcomes.

Introduction

Brain abscess is a focal area of necrosis with a surrounding membrane within the brain parenchyma, usually resulting from an infectious process or rarely from a traumatic process.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Direct Local Spread

A brain abscess can originate from infections in head and neck sites: otitis media (5%)and mastoiditis (secondarily cause inferior temporal lobe and cerebellar brain abscesses), paranasal sinus infection (approximately 30% to 50% as the reported cause), infection from frontal or ethmoid sinuses spreads to the frontal lobes, dental infection usually causes frontal lobar abscesses. Facial trauma, even from neurosurgical procedures, can result in necrotic tissue, and brain abscesses have been reported afterward. Metal fragments or other foreign bodies left in the brain parenchyma can also serve as a nidus for infection.[1][4]

Generalized Septicemia and Hematogenous Spread

Various conditions can cause hematogenous seeding of the brain. Some common ones include lung, the most common associated organ; pulmonary infections, such as lung abscess and empyema, often in hosts with bronchiectasis; or cystic fibrosis from an important encountered cause. Others include pneumonia, pulmonary arteriovenous malformation, and bronchopleural fistula. Cyanotic congenital heart diseases in children are associated with more than 60% of cases. Bacterial endocarditis, ventricular aneurysms, and thrombosis are also among the causes. Skin, pelvic and intraabdominal infections also have been reported frequently as risk factors. Brain abscesses associated with bacteremia commonly cause multiple abscesses, mostly in the distribution of the middle cerebral artery and usually at the gray-white matter junction.

The most frequent microbial pathogens isolated from brain abscesses are Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. Among this class of bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus and Viridian streptococci are the commonest.

Epidemiology

According to studies, the incidence of brain abscess is approximately 8% of intracranial masses in developing countries and 1% to 2% in the Western countries with approximately four cases occurring per million. The prevalence of brain abscess in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is higher. Therefore, the prevalence rate has increased with the emanation of the AIDS pandemic. Approximately 1500 to 2500 cases are diagnosed annually in the United States. The incidence of fungal brain abscesses also has increased because of the higher usage of broad-spectrum antibiotics and immunosuppressive agents like steroids. Prevalence is highest in adult men younger than 30 years while pediatric disease occurs most frequently in children ages 4 to 7 years. Neonates are third in high-risk groups. Vaccination has reduced the prevalence in young children. Data suggests that brain abscesses are more predominant in males than in females with a male-to-female ratio varying between 2:1 and 3:1. Geographical and seasonal differences have no significant impact. In developing countries with poor living standards, brain abscess accounts for a disproportionate percentage of space-occupying intracranial lesions compared to developed nations.[5][6]

Pathophysiology

The histologic changes depend upon the stage of the infection. The early (first 1 to 2 weeks) lesion, often called focal cerebritis, is poorly demarcated and is evident by acute inflammatory changes like vascular congestion and localized edema. This early stage is commonly called cerebritis. After two to three weeks, necrosis and liquefaction occur, which is then covered by a distinct capsule consisting of an inner layer of granulation tissue, a middle collagenous layer, and an outer astroglial layer, surrounding brain parenchyma is often edematous.

History and Physical

In about two-thirds of cases, symptoms are present for 2 weeks or less. The diagnosis is made at a mean of 8 days after the onset of symptoms. The course ranges from indolent to fulminant. Most manifestations of brain abscess tend to be nonspecific, resulting in a delay in establishing the diagnosis. Most symptoms are a direct result of the size and location of the space-occupying lesion or lesions. The triad of fever, headache, and the focal neurologic deficit is observed in less than half of patients. The frequency of common symptoms and signs is as follows:

- A headache (69% to 70%) the most common medical symptom.

- Mental status changes (65%) lethargy progressing to coma is indicative of severe cerebral edema and a poor prognostic sign.

- Focal neurologic deficits (50% to 65%) occur days to weeks after the onset of a headache.

- Pain is usually localized to the side of the abscess, and its onset can be gradual or sudden in nature. The pain is most severe in intensity and not relieved by over-the-counter pain medications.

- Fever (45% to 53%)

- Seizures (25% to 35%) can be the first manifestation of brain abscess. Grand mal seizures are particularly common in frontal abscesses.

- Nausea and vomiting (40%) are mostly seen with raised intracranial pressure

- Nuchal rigidity (15%) is most commonly associated with occipital lobe abscess or an abscess that has leaked into a lateral ventricle.

- Third and sixth cranial nerve deficits.

- Rupture of abscess usually presented with suddenly worsening headache and followed by emerging signs of meningismus.

Evaluation

Routine tests: Complete blood count with differential and platelet count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, serum C-reactive protein, serologic test, blood cultures (at least 2; preferably before antibiotic therapy).

Lumbar puncture: Rarely required and only should be performed with a prior CT and MRI scan after ruling out increased intracranial pressure because of the potential for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) herniation and death. In circumstances of acute presentation of patients or suspicion of meningitis, blood cultures can be used for the initiation of antibiotic therapy. The results are mostly nonspecific, consisting of an elevated protein level, pleocytosis with the variable neutrophil count, typically a normal glucose level, and sterile cultures. A lumbar puncture in the case of rupture when white blood cell (WBC) count becomes high in addition to elevated CSF lactic acid and abundant red blood cells (RBCs) in the CSF.

Stereotactic Computed Tomography (CT) or Surgical Aspiration

Samples obtained can be employed for culture, Gram stain, serology, histopathology, and polymerase chain reaction.

Computed Tomography

Imaging findings depend on the stage of the lesion. Early cerebritis often appears as an irregular low-density area that does not enhance or may show infrequent patchy enhancement. As cerebritis evolves, a more conspicuous rim-enhancing lesion becomes visible. Enzmann et al. reported that CT findings of patchy enhancement in early cerebritis evolve to a rim of enhancement in late cerebritis which later on forms the brain abscess. A key histopathologic difference is that rim enhancement of late cerebritis is not associated with collagen deposition as seen in an abscess where it surrounds a purulent cavity. Serial CT examinations in patients with late abscesses show progressively decreasing edema and mass effect. Brain abscess wall is usually smooth and regular with 1 mm to 3 mm thickness with surrounding parenchymal edema. The ring of enhancement may not be uniform in thickness and can be relatively thin on the medial or ventricular surface in the deep white matter, where vascularity is less abundant. Edema and contrast enhancement is suppressed by the administration of steroids. Multi-location with subjacent daughter abscesses or satellite lesions is frequently seen. Gas if presently is suggestive of gas-forming organisms.

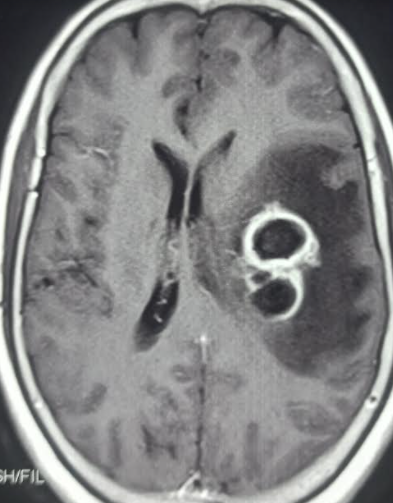

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI is the imaging modality of choice for diagnosis as well as follow-up of lesions. It is more sensitive for early cerebritis and satellite lesions particularly those present in the brain stem as well as estimating the necrosis and extent of the lesion. It allows for greater contrast between cerebral edema and the brain and is also more sensitive for detecting the spread of inflammation into the ventricles and subarachnoid space.[7][8]

Conventional spin-echo imaging with contrast

Classic MR imaging findings of an abscess include a contrast-enhanced rim surrounding a necrotic core. Rim is T1 isointense to hyperintense relative to white matter and T2 hypointense. On MRI characteristic smooth tri-laminar structure of the rim on T2W imaging proves helpful in differentiating from other ring-enhancing lesions. Central necrosis shows variable hyperintensity on T2 depending upon the degree of protein content and hypointense on T1.

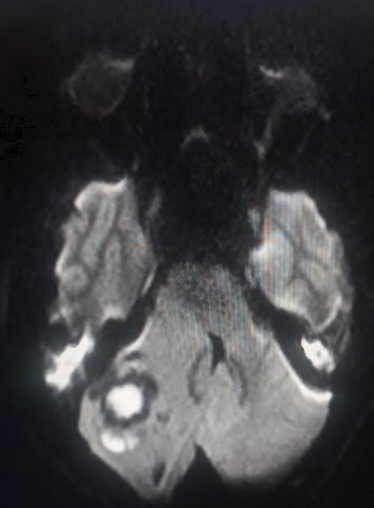

Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging

Diffusion-weighted imaging is capable of distinguishing brain abscesses from other ring-enhancing brain lesions. Abscesses are typically hyperintense on DWI (indicating restricted diffusion, characteristic of viscous materials, such as pus), while neoplasms like glioma as lack restricted diffusion appearing hypointense or variable hyperintense much lower than an abscess.

Diffusion-Tensor Imaging is based on three-dimensional diffusivity and commonly employed for the evaluation of white matter tracts. Fractional anisotropy, a quantitative variable is calculated by diffusion-tensor imaging. This variable reflects the degree of tissue organization and quite higher in abscess supposedly due to organized leukocytes in the abscess cavity.

Proton MR Spectroscopy probe tissue metabolism. Spectral analysis reveals elevated succinate, although not commonly seen is quite specific for an abscess. Other significant metabolites include elevated acetate, alanine, and lactate signals. Amino acids from neutrophil-driven protein breakdown suggest a pyogenic abscess. MR spectroscopy may be used to further differentiate anaerobic from aerobic metabolism by elevated succinate and acetate peaks which are only observed in anaerobic infections due to glycolysis and subsequent fermentation. Also, lactate peaks are lowest in strict anaerobes owing to metabolic lactate consumption.

Treatment / Management

A brain abscess can lead to elevated intracranial pressure and has significant morbidity and mortality. Management can be divided into medical and surgical approaches.

Medical management can be considered for deep-seated, small abscesses (less than 2 cm), cases of coexisting meningitis, and few other selected cases. Usually, a combination of both medical and surgical approaches is considered.[2]

CT and MRI brain guides in management by localizing the abscess and delineating details including dimensions and a number of abscesses. Usually, large abscesses (more than 2 cm) are considered for aspiration or excision based on the surgical skills of the operator. The approach for multiple abscesses includes a long course (4 to 8 weeks) of high-dose antibiotics with or without aspirations, based on weekly CT scanning.

The selection of an antibiotic regimen should be wisely made based on microorganisms isolated from blood or CSF. Certain antibiotics are unable to cross the blood-brain barrier and are not useful in treating brain abscess; these antibiotics include first-generation cephalosporins, Aminoglycosides, and tetracyclines.

Specific antibiotic regimens according to microorganisms:

- Gram-positive bacteria including streptococci: third-generation cephalosporin (e.g., cefotaxime, ceftriaxone) or penicillin G are effective

- Staph aureus, staph epidermis is usually seen in association with penetrating brain trauma and or neurosurgical procedure. It should be covered with vancomycin. It is also effective for Clostridium species. In cases of vancomycin resistance, linezolid, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or daptomycin can be considered.

- Fungal infections including Candida, Cryptococcus needs to be treated with Amphotericin B

- Aspergillus and Pseudallescheria boydii. Voriconazole can be considered

- Toxoplasma gondii infection is treated with pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine, can be combined with HAART in cases of HIV.

Steroids can be considered in select cases, especially to reduce the mass effect and improve antibiotic penetration and cerebral edema.[9]

The surgical approach has a pivotal role in the management of brain abscesses. The choice of the procedure depends on operator skills and preference. Approaches include ultrasound, or CT-guided needle aspirations via the stereotactic procedure, bur hole, and craniotomy for loculated multiple abscesses. Intravenous or intrathecal agents against specific microorganisms are considered with surgical therapy.[10]

Differential Diagnosis

The main differential diagnoses include:

- Bacterial meningitis

- Brain tumors

- Demyelination

- Epidural/subdural abscess

- Encephalitis

- Fungal or parasitic infestations: Cryptococcosis/Cysticercosis

- Mycotic aneurysm

- Septic dural sinus thrombosis

Prognosis

With the advent of antimicrobials and imaging studies as CT scanning and MRI, the mortality rate has reduced from 5% to 10%. Rupture of a brain abscess, however, is more fatal. The long-term neurological sequelae after the infection are dependent on the early diagnosis and administration of antibiotics.

Complications

The complications that can occur secondary to a brain abscess are:

- Meningitis

- Ventriculitis

- Increased intracranial pressure

- Brain herniation

- Seizures

- Septicemia

- Neurological deficits

- Thrombosis of intracranial blood vessels

- Death

Deterrence and Patient Education

The patient should be instructed on the importance of having the antibiotics for the prescribed period of time and anticonvulsants if needed. Also, the patient should report to the hospital if he/she develops new onset fever or features of raised intracranial pressure.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Brain abscess from bacterial causes remains a serious central nervous system issue despite advances in neuroimaging, neurosurgery, better antibiotics, and newer microbiological techniques.[10] If the condition is left undiagnosed or untreated, it has extremely high morbidity and mortality. The successful treatment of a brain abscess requires an integrated approach with a systemic approach to diagnosis and treatment by a number of healthcare professionals. [11] An interprofessional team approach made up of the following is highly recommended:

- Neurosurgeon drains the abscess surgically when needed

- Radiologist helps to locate and evaluate the extent of the abscess

- Laboratory technologists determine the type of microorganisms growing in the abscess

- Neurologists monitor the patient for any neurological deficits

- Infectious disease specialist determines the cause and type of antibiotics

- Pharmacist determines the type of antibiotic, management of emesis, fever, and potential drug-drug interactions

- Intensivist monitors the neuro vitals in an intensive care unit (ICU) setting

- The internist monitors the patient for any comorbidity like HIV, SIADH

- Nurses monitor the vitals, assist with the administration of medications, monitoring for any gross neurological deficits, and educating the family on home management of such patients.

Nevertheless, the appropriate management of a brain abscess does remain controversial. Current evidence-based medicine seems to be lacking in data as to which patients should be managed with medication alone, which antibiotics have the best penetrability in a brain abscess, who should undergo surgery and when, what is the efficacy of antibiotics, what is the ideal surgical approach, and what are the long-term outcomes.

To date, randomized clinical trials in the management of brain abscesses are lacking, primarily because the condition is a medical emergency that needs immediate treatment to prevent morbidity. Despite the lack of data, studies in children with brain abscesses reveal that a combined or interprofessional approach may be the best way to lower the morbidity and mortality of this serious infection.[12](Level C)