Continuing Education Activity

Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) of the knee is a somewhat rare cause of knee dysfunction and pain that has been recognized for over one hundred years, but the etiology is still poorly understood. The highest incidence is in patients between the ages of 10 and 20 years, and males have a much higher incidence of osteochondritis dissecans than females. The most common location for osteochondritis dissecans lesions of the knee is the distal femur, specifically in the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of patients who present with osteochondritis dessecans of the knee and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for those with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of osteochondritis dessecans of the knee.

- Summarize the diagnostic procedure for suspected osteochondritis dessecans of the knee, including any necessary diagnostic imaging.

- Outline the various treatment options for osteochondritis dessecans of the knee.

- Explain possible interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance the evaluation and treatment of osteochondritis dessecans of the knee and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) of the knee is a somewhat rare cause of knee dysfunction and pain that has been recognized for over one hundred years, but the etiology is still poorly understood.[1] The ROCK (Research in Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee) Study Group recently summarized the currently recognized pathophysiology of osteochondritis dissecans as being an acquired subchondral lesion characterized by osseous resorption, collapse, and sequestrum formation.[1][2][3] While the term osteochondritis dissecans was originally proposed by Konig in 1887 to suggest an inflammatory etiology for these mysterious osteochondral lesions, the exact etiology is still unknown.[4] The highest incidence is in patients between the ages of 10 and 20 years, and males have a much higher incidence of osteochondritis dissecans than females.[5] The most common location for osteochondritis dissecans lesions of the knee is the distal femur, specifically in the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle.[6]

Patients with osteochondritis dissecans can present with knee pain as the primary complaint, or osteochondritis dissecans can be discovered incidentally on radiographs obtained for unrelated injuries.[1] Osteochondritis dissecans lesions are diagnosed with imaging, and most can be identified with plain radiographs.[1] The most important prognostic factor involves the skeletal age of the patient at the time of symptom onset.[7] More than half of pediatric osteochondritis dissecans cases treated conservatively will demonstrate healing within 6 to 18 months, while adults with osteochondritis dissecans of the knee frequently require surgery.[6]

Etiology

While it has been more than 125 years since Konig first described the term osteochondritis dissecans, the exact etiology remains a mystery. Numerous hypotheses exist for the precise etiology of osteochondritis dissecans, including inflammatory, vascular/ischemic, trauma/microtrauma, and hereditary/genetic causes, although none have been proven definitive.[8] Although there is no universal agreement regarding etiology of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee, repetitive trauma has been recognized as the most commonly accepted cause.[1]

Epidemiology

Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee is much more commonly diagnosed in young patients, mostly affecting patients between the ages of 10 and 20.[3][7] Patients aged 12 to 19 have 3.3 times increased incidence of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee compared to patients aged 6 to 11.[9][10]The overall prevalence of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee is between 9.5 and 29 per 100,000 population, and males have a 2 to 4 times higher incidence of osteochondritis dissecans than females.[2][7][11]

Pathophysiology

The lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle (64%) is the most common location for osteochondritis dissecans lesions in the knee, followed by the lateral femoral condyle (32%).[9][10] As osteochondritis dissecans lesions of the knee progress, they may change from being stable to unstable. This progression may cause articular cartilage breakdown, resulting in loose bodies as well as osteochondral tissue loss.[9] Mechanical symptoms or knee effusion can indicate unstable osteochondritis dissecans lesions, which can be evaluated with MRI. Unstable osteochondritis dissecans lesions on MRI can show increased T2 signal at the articulation of the host bone and the lesion or destruction of overlying articular cartilage. If there are multiple cyst-like foci or a single focus larger than 5 mm, that may also be a sign of osteochondritis dissecans lesion instability on MRI.[9][12]

History and Physical

High clinical suspicion should be maintained as the presentation of osteochondral lesions can mimic several much more common causes of knee pain. The historical features and symptoms of osteochondritis dissecans lesions lie along a spectrum depending on the age of the patient and disease progression at presentation. Asymptomatic osteochondritis dissecans may be discovered incidentally on plain radiographs taken for other reasons while advanced stages may present similarly to an acute knee injury once a loose body is present. Important historical questioning includes a history of trauma, a recent increase in activity level, previous knee injuries and the presence of mechanical symptoms. Pain during weight bearing is the most commonly reported symptom, occurring in approximately 80% of symptomatic osteochondritis dissecans cases.[13] A distinction is typically made between juvenile and adult knee osteochondritis dissecans based on the patient’s skeletal maturity at the time of diagnosis. In juvenile osteochondritis dissecans, the pain is often intermittent, associated with activity and poorly localized around the anterior aspect of the joint, while adults with osteochondritis dissecans lesions are much more likely to present with effusion, limited range of motion or mechanical symptoms such as catching or locking.[2] Depending on the chronicity of the lesion, patients may report quadriceps dysfunction and intermittent knee instability.[6]

As mentioned above, osteochondritis dissecans lesions of the knee may be completely asymptomatic, stressing the importance of a comprehensive physical examination to rule out other causes of knee pain. Inspection of knee alignment may reveal genu varus, associated with a lesion at the medial femoral condyle, or genu valgus, more common with osteochondritis dissecans of the lateral femoral condyle.[13] Palpation may reveal effusion or bony tenderness along the femoral condyles with varying degrees of knee flexion. The patient's range of motion may be limited secondary to pain, swelling or a loose body compared to the contralateral knee. Special tests for osteochondritis dissecans lesions, although limited, have been described. Wilson’s test, specific for lesions of the medial femoral condyle, involves simultaneous internal rotation of the tibia and passive extension of the knee from 90 degrees to 30 degrees. Pain elicited with internal rotation and relieved by external rotation indicates a positive test, which is theorized to represent impingement of the osteochondritis dissecans lesion by the medial tibial eminence.[13] With this in mind, it is advisable to watch the patient walk, which may reveal the rotation of the affected tibia to decrease pressure on the osteochondritis dissecans lesion.

Evaluation

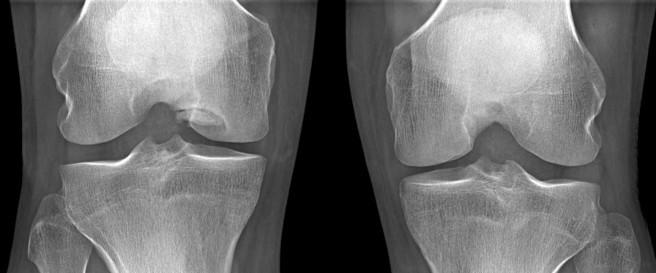

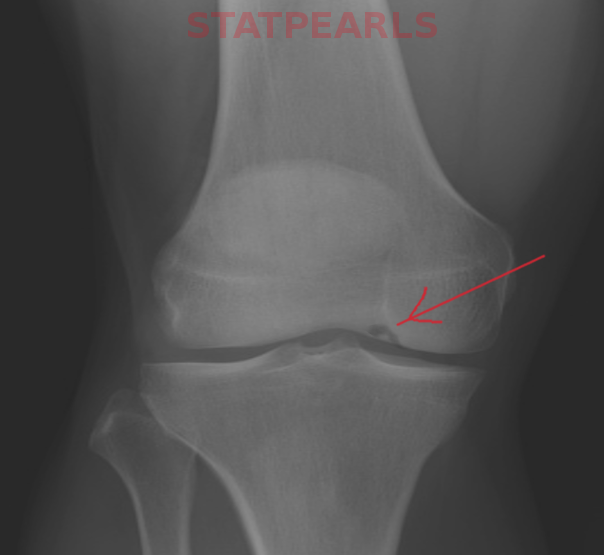

Like many orthopedic conditions, evaluation begins with plain radiographs in order to localize the lesion, evaluate the growth plates and rule out other conditions. The typical series includes standing A/P, lateral, sunrise and notch views. Osteochondritis dissecans lesions are often initially missed on radiographs. The notch view, an A/P projection taken in 30 to 50 degrees of knee flexion, allows for better evaluation of the posterior femoral condyles.[2] Cahill and Berg suggested classification based on the location of the lesion in which the knee is divided into 15 anatomic zones.[2] This is rarely used clinically but lesion location does provide important prognostic information as less common, atypical locations such as the trochlea or patella may not do as well with conservative management.[14] Lesions are identified and described throughout the literature as well-defined lucent areas of bone with varying levels of density, with or without calcifications and lucent lines separating the fragment from the bone, depending on the severity of the lesion.

Plain radiographs are limited in determining the stability of osteochondritis dissecans lesions, which is vitally important for clinical decision making. As a result, magnetic resonance imaging is often indicated for further evaluation. MRI allows for more precise evaluation of the size of the lesion in addition to the structure of the overlying cartilage. Hefti et. al developed a classification system based on magnetic resonance findings as listed below.[15]

Stage

- A small change of signal in the subchondral bone without clear margins

- Osteochondral lesion with clear margins, no underlying fluid between fragment and bone

- Fluid partially visible between the fragment and underlying bone

- Fluid completely surrounding fragment, fragment remains in situ

- Loose body

Several authors have studied the correlation between MRI findings and the prognosis of osteochondritis dissecans lesions. De Smet et al. described several T2 weighted MRI signs that may be associated with an unstable lesions including a line of intense signal equal to that of fluid at the fragment-bone interface measuring 5 mm or more in length, a discrete round focus of intense signal deep to the osteochondritis dissecans lesion measuring 5 mm or more, a focal defect in the overlying articular cartilage that measures 5 mm or more in width and an intense signal equal to that of fluid that traverses both the articular cartilage and subchondral bone and extends into the lesion.[16][17] Of these, a line of high signal intensity between the fragment and underlying bone was found to be most sensitive for instability.[16][17] Unstable lesions are less likely to heal with non-operative management.

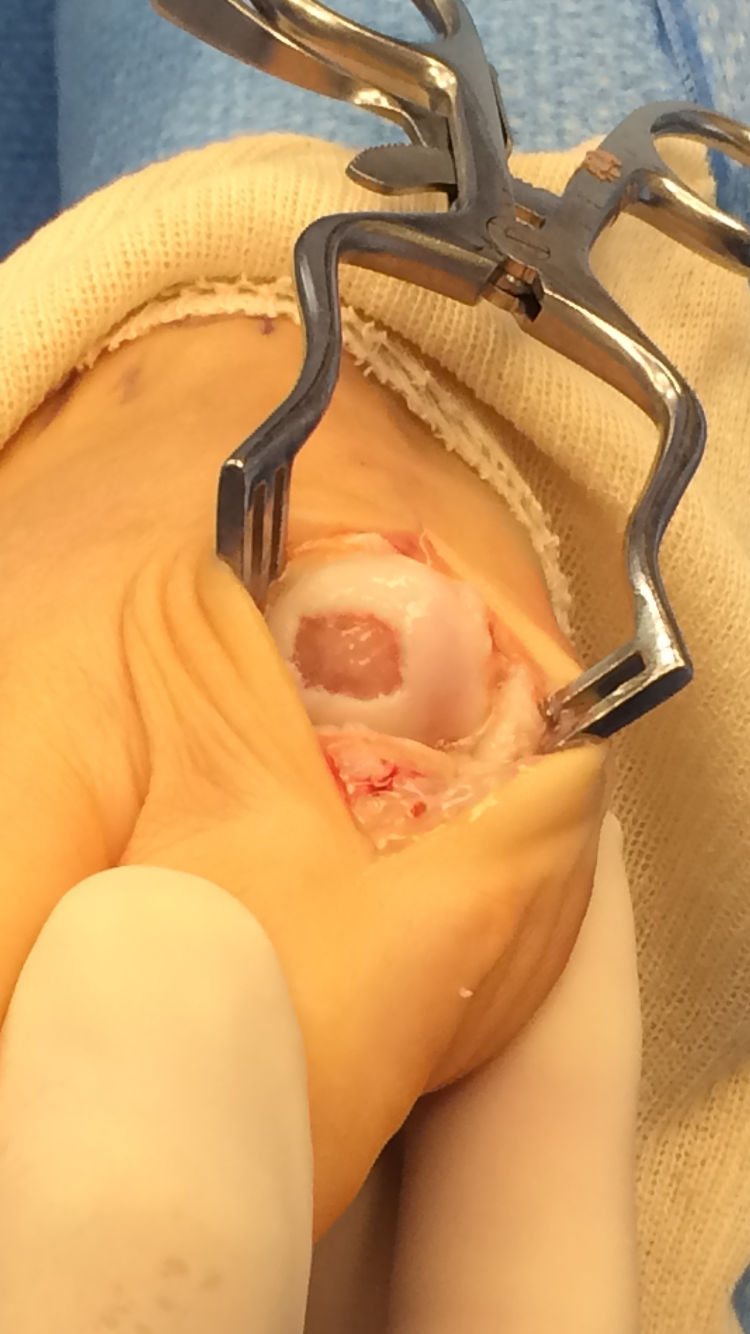

Ultimately, arthroscopy in the gold standard for assessing lesion stability and determining the appropriate management. The International Cartilage Repair Society developed an intraoperative classification which defines the integrity and stability of the fragment, as described below.[18]

Types

- Softening of intact cartilage

- Cartilage breached, stable fragment when probed

- Fragment discontinuity, unstable when probed, the fragment is in place

- Osteochondral crater and loose body

Treatment / Management

The treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee includes both conservative and surgical approaches. The approach depends on severity, age, and location of the disease.

Conservative approaches to treatment can be considered in juvenile patients with stage I to III disease and asymptomatic adults with stage I disease. Conservative therapy is preferred if the lesions are stable with no loose bodies or there are open physes. If osteochondritis dissecans of the knee is diagnosed incidentally in an asymptomatic patient, no treatment is necessary, but the patient should be followed until documented radiographic healing occurs.[13] For patients with symptomatic osteochondritis dissecans of the knee, conservative strategies include non-weight bearing and immobilization for 1 to 2 weeks, activity restriction followed by progression to light activity with no high-impact activity for 6 to 12 weeks. Physical therapy strategies include isometric quadriceps exercises in addition to stretching and soft tissue modalities. Return to activity can occur when there is no pain, a normal exam, and x-ray showing healing.[19]

A surgical approach to osteochondritis dissecans of the knee is used if conservative therapy is not appropriate or if conservative therapy fails after 3 to 6 months. A surgical approach is a primary treatment in adults with any symptoms related to osteochondritis dissecans, or in patients who have at least stage II disease. Juveniles start with surgery if the lesion is unstable, if there are loose bodies, or if physes have closed.[19] Several surgical techniques can be considered. An arthroscopic approach can be considered if the patient fails conservative therapy, there is impending physeal closure, or if there is joint instability.[20] If the osteochondritis dissecans lesion looks stable during arthroscopy, the patient may undergo subchondral drilling with k-wire placement, which leads to the formation of fibrocartilage tissue and is a good approach for skeletally immature patients. If arthroscopy shows an unstable osteochondritis dissecans lesion or if MRI shows a lesion greater than 2 cm, then the lesion should be repaired by fixation of the unstable lesion.[21] For lesions greater than 2 cm by 2 cm, chondral resurfacing can also be considered, and several different techniques can accomplish this. Microfracture surgery stimulates healing to increase fibrocartilage that leads to good short term results; however, it has decreased durability and increased failure rates.[20] Osteochondral allografts can also be considered, but the grafts are very expensive. Autologous graft procedures lead to the native bone to bone healing that can result in faster recovery. Additionally, periosteal patches are implants that regenerate cartilage and have shown promise clinically.[22] Lastly, for patients over 60 years old, arthroplasty is usually the recommended surgical approach to treatment.[20]

Differential Diagnosis

As the symptomatology of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee can vary from asymptomatic to vague pain with weight-bearing to the extremes of effusion and mechanical symptoms, the differential diagnosis is broad. For the typical osteochondritis dissecans patient in the pediatric age range experiencing atraumatic knee pain with weight-bearing, the differential would include patellofemoral syndrome, patellar tendonitis, Osgood-Schlatter disease, Sinding-Larsen-Johannson syndrome, fat pad impingement, symptomatic discoid meniscus, and symptomatic synovial plica. For an adult with typical weight-bearing knee pain, the differential would include patellofemoral pain, knee osteoarthritis, chondromalacia, patellar tendonitis, meniscal tear, fat pad impingement, and symptomatic synovial plica. For adults with more severe atraumatic edema as well as mechanical symptoms in the knee, the differential would include a meniscal tear, osteochondral loose body, and neoplasm.

Prognosis

The prognosis of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee depends on patient age, location and appearance of the lesion on imaging. In general, younger patients do better than adults with osteochondritis dissecans of the knee. Specifically, pediatric patients with open distal femoral physes have the best prognosis for complete recovery with conservative measures. Adults with the disease often progress to arthritis if not treated.[19] Location of the lesion also matters as patients with osteochondritis dissecans lesions on the lateral femoral condyle or patella have a lower rate of full recovery. Patients with higher stages of disease on imaging also have a worse prognosis. Lesions that show sclerosis on x-ray or synovial fluid behind the lesion on MRI have a less successful recovery.[23] Patients who allow their bodies to heal fully are usually able to gain complete recovery of their function. Patients with more severe stage III or IV lesions who do not have a full recovery often progress to chronic pain, mechanical symptoms, and arthritic disease.[24]

Complications

As mentioned above in the treatment section, patients who fail conservative treatment strategies for osteochondritis dissecans of the knee typically require surgery for full recovery. As stated in the prognosis section, patients with higher stages of osteochondritis dissecans lesions who do not fully heal or who fail surgical therapies often progress to chronic pain, mechanical symptoms, and arthritic disease.[24]

Deterrence and Patient Education

The exact etiology of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee has not been confirmed, and there are no clear guidelines for the prevention or deterrence of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee. Patients with osteochondritis dissecans of the knee who are between the ages of 10 and 20 should receive education and encouragement regarding the high success rates of conservative management. Adults with osteochondritis dissecans of the knee should be informed that there is a high likelihood surgical therapy will be required to help them fully recover.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Osteochondritis of the knee can pose a diagnostic dilemma, as the lesion may either be asymptomatic or mimic other causes of knee pain. Managing osteochondritis dissecans of the knee requires an interprofessional team of healthcare professionals that includes a physician, physical therapists for conservative management, a radiologist trained in reading musculoskeletal imaging, and an experienced orthopedic surgeon. The physician will need to keep osteochondritis dissecans of the knee in their differential diagnosis for possibly vague presentations of knee pain and must order the correct radiographs as well as MRI for proper identification and staging of these lesions. Physical therapists will be required to manage most patients with osteochondritis dissecans of the knee properly, whether they receive conservative therapy or surgical therapy and need strengthening as well as gait retraining after a period of non-weight bearing. A well-trained radiologist will be required to identify and grade osteochondritis dissecans lesions in the knee properly. An experienced orthopedic surgeon is essential to provide guidance regarding the likelihood of successful treatment with conservative therapy versus surgery. Timely diagnosis and recognition are critical, as stable osteochondritis dissecans lesions with intact articular surfaces are likely to heal with nonoperative treatment, especially in pediatric patients.[6] (Level V). As the exact etiology of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee remains a mystery, prevention of this diagnosis continues to appear untenable.