Continuing Education Activity

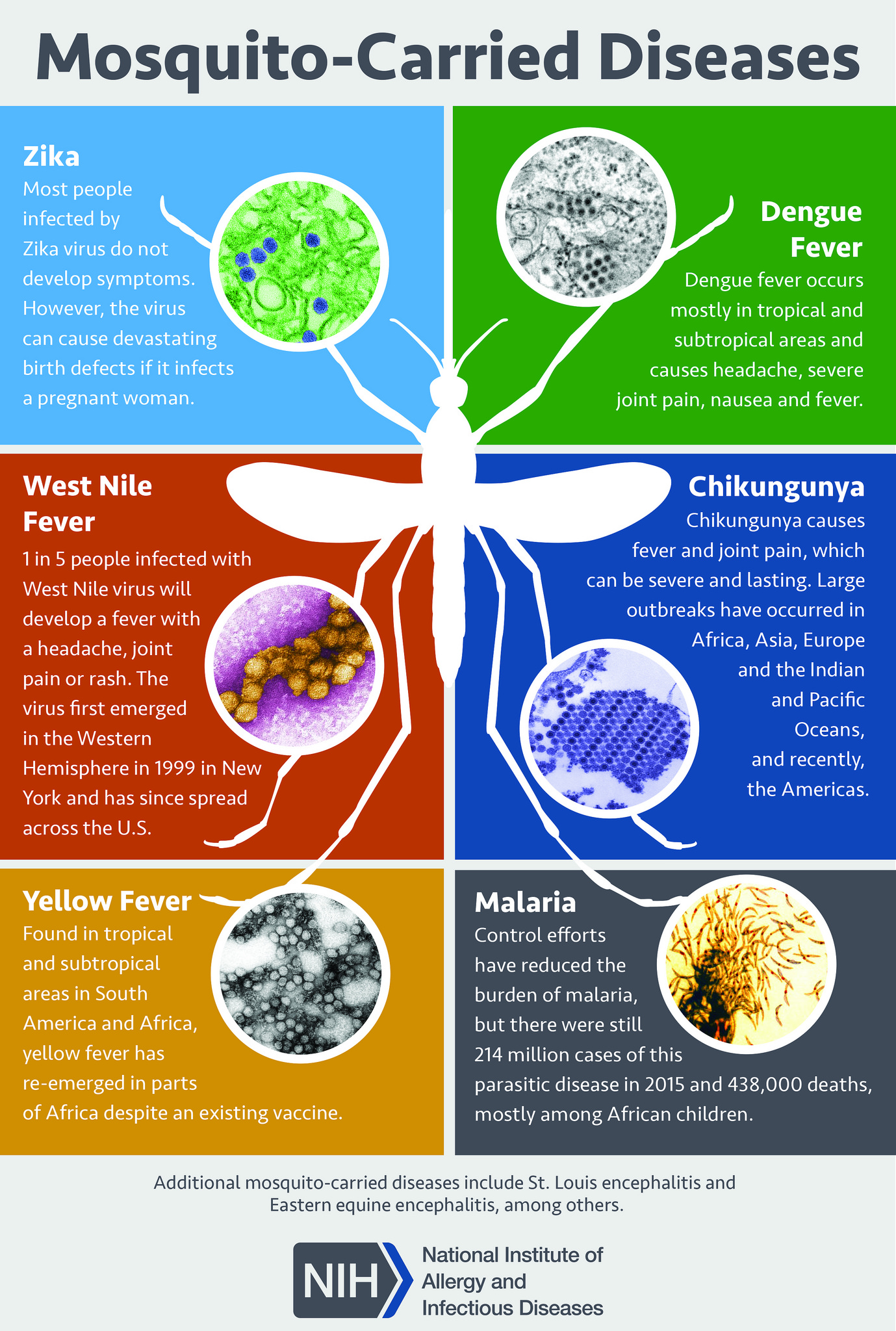

Dengue is a mosquito-transmitted virus and the leading cause of arthropod-borne viral disease in the world. It is also known as breakbone fever due to the severity of muscle spasms and joint pain, dandy fever, or seven-day fever because of the usual duration of symptoms. Although most cases are asymptomatic, severe illness and death may occur. Aedes mosquitoes transmit the virus and are common in tropical and subtropical parts of the world. The incidence of dengue has increased dramatically over the past few decades, and the infection is now endemic in some parts of the world. A few people who were previously infected with one subspecies of the dengue virus develop severe capillary permeability and bleeding after being infected with another subspecies of the virus. This illness is known as dengue hemorrhagic fever. This activity reviews the etiology, presentation, evaluation, and management of dengue fever and examines the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating, diagnosing, and managing the condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of dengue fever.

- Review the symptomatic presentation of dengue fever along with physical exam findings.

- Discuss the available management options for dengue fever, including prevention strategies.

- Explain the importance of interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to aid in prompt diagnosis of dengue fever and improve outcomes in patients diagnosed with the condition.

Introduction

Dengue is a mosquito-transmitted virus and the leading cause of arthropod-borne viral disease in the world. It is also known as breakbone fever due to the severity of muscle spasms and joint pain, dandy fever, or seven-day fever because of the usual duration of symptoms. Although most cases are asymptomatic, severe illness and death may occur. Aedes mosquitoes transmit the virus and are common in tropical and subtropical parts of the world. The incidence of dengue has increased dramatically over the past few decades. The infection is now endemic in some parts of the world. A few people who were previously infected with one subspecies of the dengue virus develop severe capillary permeability and bleeding after being infected with another subspecies of the virus. This illness is known as dengue hemorrhagic fever.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Dengue fever is caused by any of four distinct serotypes (DENV 1-4) of single-stranded RNA viruses of the genus Flavivirus. Infection by one serotype results in lifelong immunity to that serotype but not to others.[4][5][6]

Epidemiology

It is the fastest spreading mosquito-borne viral disease globally, affecting greater than 100 million humans annually. Dengue also causes 20 to 25,000 deaths, primarily in children, and is found in more than 100 countries. Epidemics occur annually in the Americas, Asia, Africa, and Australia. Two transmission cycles maintain the dengue virus: 1) mosquitos carry the virus from a non-human primate to a non-human primate, and 2) mosquitos carry the virus from human to human. The human-mosquito cycle occurs primarily in urban environments. Whether the virus transmits from human to mosquito depends on the viral load of the mosquito’s blood meal.

The primary vectors of the disease are female mosquitoes of the species Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Although A. aegypti is associated with most infections, A. albopictus’ range is expanding, tolerates cold environment better, is an aggressive feeder but feeds less frequently, and may be associated with increasing numbers. These species of mosquitoes tend to live indoors and are active during the day. Transmission by perinatally, blood transfusions, breast milk, and organ transplantation have been reported.

After 2010, the mean age of patients was 34 years compared to 27.2 years from 1990 to 2010. The dengue viral serotype causing disease outbreaks have varied with time, as has the occurrence of severe dengue fever.[7][8]

Transmission of dengue generally follows two patterns - epidemic dengue and hyperendemic dengue. When a single strain of DENV is responsible for introduction and transmission it is referred to as epidemic dengue. Dengue epidemics were more common prior to World War II. During an epidemic, all age groups are affected, but the incidence of dengue hemorrhagic fever is relatively low. Hyperendemicity refers to the co-circulation of various serotypes of DENV in a community. Periodic epidemics in an area are linked to the emergence of hyperendemicity.[9] Children are affected more than adults, and the incidence of DHF is relatively higher.

Pathophysiology

Part of the Flavivirus family, the dengue virus is a 50 nm virion with three structural and seven nonstructural proteins, a lipid envelope, and a 10.7 kb capped positive-sense single strand of ribonucleic acid. Infections are asymptomatic in up to 75% of infected humans. A spectrum of diseases, from self-limiting dengue fever to hemorrhage and shock, may be seen. A fraction of infections (0.5% to 5%) progress to severe dengue. Without proper treatment, fatality rates may exceed 20%. These occur primarily in children. The typical incubation period for the disease is 4 to 7 days, but it can last from 3 to 10 days. Symptoms more than two weeks after exposure are unlikely to be due to dengue fever.

The exact course of events following the dermal injection of the dengue virus by a mosquito bite is unclear. Skin macrophages and dendritic cells appear to be the first targets. It is thought that the infected cells then move to the lymph nodes and spread through the lymphatic system to other organs. Viremia may be present for 24 to 48 hours before the onset of symptoms. A complex interaction of host and viral factors then occurs and determines whether the infection will be asymptomatic, typical, or severe. Severe dengue fever with increased microvascular permeability and shock syndrome is thought to be associated with infection due to a second dengue virus serotype and the patient's immune response. However, cases of severe dengue do occur in the setting of infection by only a single serotype. Worsening microvascular permeability often transpires even as viral titers fall.

History and Physical

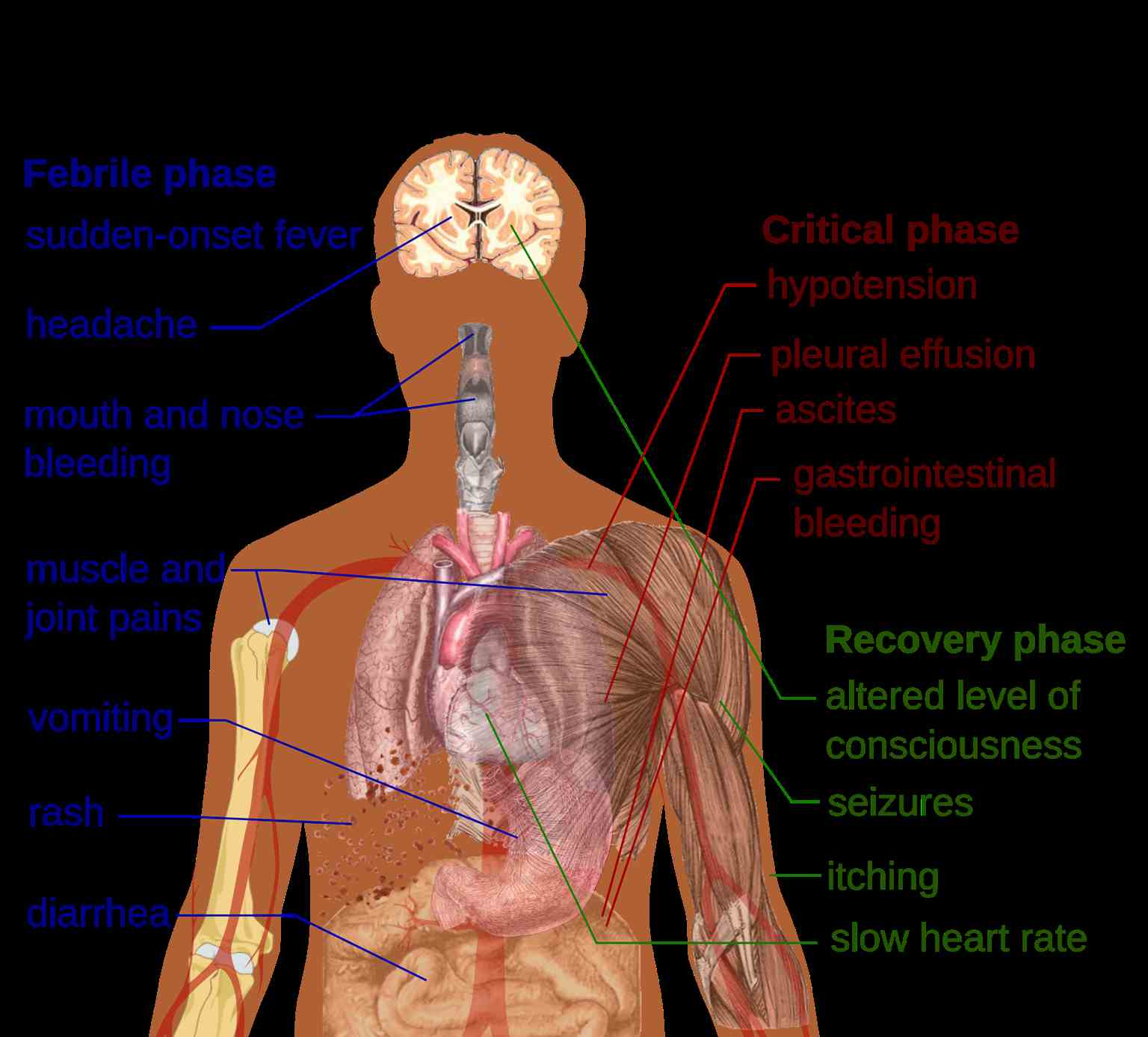

The three phases of dengue include febrile, critical, and recovery.

During the febrile phase, a sudden high-grade fever of approximately 40 C occurs that usually lasts two to seven days. Saddleback or biphasic fever is seen in approximately 6% of cases, particularly in patients with DHF and severe dengue. It is described as a fever that remits at least for one day, and the next fever spike starts, which lasts at least for one more day.[10] Associated symptoms include facial flushing, skin erythema, myalgias, arthralgias, headache, sore throat, conjunctival injection, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting. For skin erythema, a general blanchable macular rash occurs in the first one to two days of fever and the last day of fever. Or, within 24 hours, a secondary maculopapular rash can develop.

Defervescence characterizes the critical phase with a temperature of approximately 37.5 C to 38 C or less on days three through seven. It is associated with increased capillary permeability. This phase usually lasts one to two days. The onset of the critical phase is heralded by a rapid decline in platelet count, rise in hematocrit (the patient may have leukopenia up to 24 hours before platelet count drops), and the presence of warning signs. It can progress to shock, organ dysfunction, disseminated intravascular coagulation, or hemorrhage.

The recovery phase entails the gradual reabsorption of extravascular fluid in two to three days. The patient will display bradycardia at this time.

Expanded dengue syndrome refers to unusual or atypical manifestations in patients with dengue with neurological, hepatic, renal, and other isolated organ involvement. It could be due to profound shock. Neurological manifestations include febrile seizures in young children, encephalitis, aseptic meningitis, and intracranial bleeding. Gastrointestinal involvement may be seen in the form of hepatitis, liver failure, pancreatitis, or acalculous cholecystitis. It may also manifest as myocarditis, pericarditis, ARDS, acute kidney injury, or hemolytic uremic syndrome.

Evaluation

Common laboratory findings include thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, elevated aspartate aminotransferase. The disease is classified as dengue or severe dengue.[11][12][13]

Criteria for Dengue Include

- Probable dengue: The patient lives in or has traveled to a dengue-endemic area. Symptoms include fever and two of the following: nausea, vomiting, rash, myalgias, arthralgias, rash, positive tourniquet test, or leukopenia.

- Warning Signs of Dengue: Abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, clinical fluid accumulation such as ascites or pleural effusion, mucosal bleeding, lethargy, liver enlargement greater than 2 cm, increase in hematocrit, and thrombocytopenia.

- Severe Dengue: Dengue fever with severe plasma leakage, hemorrhage, organ dysfunction including transaminitis greater than 1000 international units per liter, impaired consciousness, myocardial dysfunction, and pulmonary dysfunction

- Dengue shock syndrome clinical warnings: Symptoms include rapidly rising hematocrit, intense abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, and narrowed or absent blood pressure.

The virus antigen is detectable by ELISA, polymerase chain reaction, or virus isolation from body fluids. Serology will reveal a marked increase in immunoglobulins. A confirmed diagnosis is established by culture, antigen detection, polymerase chain reaction, or serologic testing.

It is vital to assess pregnant patients with dengue as the symptoms may be very similar to preeclampsia.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of dengue depends on the patient's illness phase. Those presenting early without any warning signs can be treated on an outpatient basis with acetaminophen and adequate oral fluids. Such patients should receive an explanation regarding the danger signs and be asked to report to the hospital immediately if they notice any. Patients with warning signs, severe dengue, or other situations like infancy, elderly, pregnancy, diabetes, and those living alone need to be admitted. Those with warning signs can be initiated on IV crystalloids, and the fluid rate is titrated based on the patient's response. Colloids can be started for patients in shock and are also preferred if the patient has already received previous boluses of crystalloid and has not responded. Blood transfusion is warranted in case of severe bleeding or suspected bleeding when the patient remains unstable, and hematocrit falls despite adequate fluid resuscitation. Platelet transfusion is considered when platelet count drops to <20,000 cells/microliter, and there is a high risk of bleeding. Avoid giving aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and other anticoagulants. No antiviral medications are recommended.

No laboratory tests can predict the progression to severe disease.

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of dengue can be challenging as many other illnesses can present similarly early in the disease course. Other considerations should include malaria, influenza, Zika, chikungunya, measles, and yellow fever. Obtain a detailed history of immunizations, travel, and exposures.

Rapid laboratory identification of dengue fever includes NS1 antigen detection and serologic tests. Serologic tests are only useful after several days of infection and may be associated with false positives due to other flavivirus infections, such as yellow fever or Zika virus.

Prognosis

Untreated severe dengue fever may have a mortality rate of 10% to 20%. Appropriate supportive care reduces the mortality rate to roughly 1%.

Complications

- Liver injury

- Cardiomyopathy

- Pneumonia

- Orchitis

- Oophoritis

- Seizures

- Encephalopathy

- Encephalitis

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Patients should be encouraged to consume ample liquids. The return of a patient's appetite is a sign that the infection is subsiding.

Consultations

Consulting an infectious disease specialist is recommended because most clinicians have little experience managing this infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has a hotline that also offers treatment advice.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The only way to avoid contracting dengue is to prevent mosquito bites and not travel to endemic areas.

Preventative measures include [14]-

Personal Prophylactic Measures: Use of bed nets while in bed even in the daytime, Insecticide-treated materials (ITMs) like window curtains, application of mosquito repellent creams (containing DEET, IR3535, or Icaridin), coils, developing the habit of wearing full sleeve shirts and pants help prevent mosquito bite.

Biological Control

a) Fish: Viviparous species Poecilia reticulata have been used in confined water bodies like large water tanks, open freshwater wells. Only native larvicidal fishes should be used.

b) Predatory Copepods: These small freshwater crustaceans have proven to be effective only in specific container habitats

c) Endosymbiotic control: Mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia (an intracellular parasite) are less susceptible to DENV infection than wild type A. aegypti.[15]

Chemical Control: Larvicidal use in big breeding containers; Insecticide spray: Space sprays can be applied as thermal fogs and cold aerosols. Oil-based formulations are preferred as it inhibits evaporation. Some of the commonly used insecticides are organophosphorus compounds (fenitrothion, malathion) and pyrethroids (bioresmethrin, cypermethrin).

Environmental Measures: Finding the breeding areas and eliminating the pests; proper management of rooftops and sunshades; appropriate covering of stored water like buckets, pots, etc

Health Education: It is the most important weapon to fight against dengue. Sensitizing the people regarding dengue in detail is necessary for the effective implementation of the dengue control program. The sensitization can be done by audiovisual media or mass awareness campaigns.

Community Participation: It's essential to sensitize the communities for their active participation in dengue control programs.

Vaccination: CYD-TDV: a live recombinant tetravalent dengue vaccine, first to be licensed, is approved for endemic areas in 20 countries.[16]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of dengue are complex, and this is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes an infectious disease expert, a CDC consultant, an emergency department clinician, and an internist. The care is supportive with fluid, acetaminophen for fever, and a blood transfusion for hemorrhage. A confirmed diagnosis is established by culture, antigen detection, polymerase chain reaction, or serologic testing. No laboratory tests can predict the progression to severe disease.

The role of the primary care provider and nurse practitioner is to educate the traveler on the prevention of mosquito bites. This means covering exposed skin and using bed nets, particularly during daytime siestas, using mosquito repellents, and indoor insecticides. One should also eradicate mosquito breeding grounds like standing water. The prognosis for untreated dengue is abysmal, but most patients can survive with supportive care, albeit with residual multisystem organ damage.[17][18]