Continuing Education Activity

Tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN) is a group of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases that involves the interstitium and tubules. Inflammation of the kidney consists of the collection of inflammatory cells, fluid, and extracellular matrix surrounding the interstitium, along with the infiltration of tubular cells by inflammatory cells that define both tubules and interstitium pathology. It is one of the most important and significant causes of acute kidney injury that subsequently leads to renal failure. There are multiple causative factors of tubulointerstitial nephritides, including drug-induced, idiopathic, genetic, immune-mediated, and infectious (viral, bacterial, parasitic, or fungal). In addition, there is an association of systemic inflammatory conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren disease, immunoglobulin G4 associated autoimmune disease (interstitial infiltration of IG4 positive plasma cell and C3 deposition), tubulointerstitial nephritis, and uveitis syndrome. This activity highlights the role of interprofessional team members in managing patients with tubulointerstitial nephritis for best patient outcomes.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of tubulointerstitial nephritis.

- Outline the appropriate evaluation of tubulointerstitial nephritis.

- Summarize the management options available for tubulointerstitial nephritis.

- Describe interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance tubulointerstitial nephritis and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN) is a group of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases that involves the interstitium and tubules. Inflammation of the kidney consists of the collection of inflammatory cells, fluid, and extracellular matrix surrounding the interstitium, along with the infiltration of tubular cells by inflammatory cells that define both tubules and interstitium pathology. It is one of the most significant causes of acute kidney injury that leads to renal failure. TIN can be classified into acute and chronic based on underlying etiology, duration, or histology.[1]

Renal impairment with acute TIN is reversible, provided early and appropriate interventions are made, but chronic TIN may be irreversible in severe cases. Drug-induced nephritis is widely described and is the leading cause of TIN. Delay in diagnosis due to nonspecific signs and symptoms is frequently seen; thus, many attempts have been made for effective diagnosis and exclude the other differentials carefully through efficient clinical experts' opinions and assessment and diagnostic tests.

Etiology

There are multiple causative factors of tubulointerstitial nephritis, such as drug-induced, idiopathic, genetic, immune-mediated, and infectious (viral, bacterial, parasitic, or fungal). Associated are systemic inflammatory conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjögren disease, immunoglobulin G4 associated autoimmune disease (interstitial infiltration of IG4 positive plasma cell and C3 deposition), tubulointerstitial nephritis, and uveitis syndrome.[2] The most important etiology is medication (beta-lactam antibiotics, sulphonamides, proton pump inhibitors, 5-aminosalicylates, rifampicin, and NSAIDs) which consists of 50% to 80%, sometimes up to 92% of the total cases, idiopathic 8%, and other 15%.[3][4] The most common etiology among medications is NSAIDs (44%), followed by antibiotics (33%) and proton pump inhibitors (7%).[5]

TIN is the third leading cause of renal transplant dysfunction, whereas transplant rejection in already immunocompromised patients is mainly due to infections, including polyomavirus or cytomegalovirus. Bone marrow transplant recipients are mainly associated with necrotizing TIN due to adenovirus. TIN and uveitis syndrome are associated with the Epstein-Barr virus and bacteria like leptospira, mycoplasma, and yersinia.[6][7] Anti-tubular basement membrane antibodies are also involved in the TIN. In most cases of TIN by bacteria, the renal pelvis is prominently involved; hence the absolute term pyelonephritis is used. The term interstitial nephritis generally is reserved for cases of TIN that are nonbacterial in origin, i.e., tubular injury by drugs, hypokalemia, immune reactions (autoimmune), irradiation, and viral infections. The TIN antigen is an extracellular basement membrane protein, and the deletion of the TIN antigen leads to disruption of the basement membrane structure, predisposing to the TIN.[2]

Epidemiology

Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis is the leading cause of acute kidney injury (AKI). The global prevalence of acute TIN is 1 to 3% among all renal biopsies. The overall prevalence of acute TIN increased to 15-27% when the analysis was restricted to only AKI cases.[8][9][10][11][12] Analysis of kidney biopsy registries from 120 hospitals in Spain affirmed 2.7% of acute TIN and 17% of which complicated to acute kidney injury. When only AKI patients were analyzed, the prevalence was increased to 13% in Spain, which is similar to elsewhere.[13]

In this study, most patients accounted for adults and the elderly, and only 5% were children, male (53%) compared to females (47%). Data analysis from Czech registries of renal biopsies insisted the rate of TIN was 4%, but when analyzed only among the patients with renal insufficiency, it was around 12%.[14] There is an increase in the incidence of TIN from 3% to up to more than 12% among older adults, mainly due to the increased use of antibiotics and NSAIDs in that population group.

Pathophysiology

High metabolic demand and relatively less blood supply make the tubulointerstitium susceptible to injury. The kidney has a higher exposure to drugs and toxins, increasing renal injury chances.[15] TIN mainly involves inflammation and edema of the interstitium, which compromises the blood supply further and ultimately causes a decrease in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). The glomerulus is relatively spared and involved only in late and severe stages. Initially, offending agents damage tubular cells and interstitium, causing acute TIN. However, chronic TIN is referred to long-standing and progressive cases characterized by irreversible deterioration of renal function due to tubular atrophy and fibrosis.

Production and activation of cytokines, such as tissue necrosis factors alpha (TNF-alpha) by inflammatory cells (lymphocytes, macrophages) and renal cells (interstitial fibroblasts, vascular endothelial cells, proximal tubular cells), escalate the inflammatory process. Macrophages are initially responsible for repair but later contribute to inflammation by producing fibrogenic cytokines, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta). TGF-beta is responsible for fibrosis in chronic TIN. Tubular atrophy leads to burnout and a decrease in the number of nephrons, which overwhelms the functioning capacity of remaining nephrons by hyperfiltration leading to chronic kidney disease (CKD). TGF-beta favors the accumulation of collagen in the extracellular matrix and basement membrane and inhibits the collagenase and metalloproteinase enzymes. In the setting of tubular necrosis, a complex series of necrosis-induced inflammation, i.e., neuroinflammation, has a role in the pathogenesis of TIN. Injured renal tubular cells lose their polarity and integrity and undergo apoptosis and necrosis. Necrosed cells express various danger-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) and alarmins, which activates the immune response to induce inflammation. This process of intensifying inflammation through necrosed tubular cells is known as necroinflammation.[15][16]

Drug-induced TIN is a result of allergic reactions and is immune-mediated. Only small proportions of the population taking the same medications have TIN, mainly due to variable responses of individuals to the same drug.[17] It is dose-independent and shows systemic manifestations of hypersensitivity.[1] The primary pathogenic mechanism of interstitium in the drug-induced TIN is type IV hypersensitive reactions in which T cells (71% CD8+ and CD4+ equally) have a central role, but monocytes (15%) and B cells (7%) are also involved. Acute tubular injury is due to the direct toxicity of drugs and the progression of inflammatory infiltration of the interstitium.[15] Drugs act as hapten either by mimicking or directly binding to the tubular cell's basement membrane, stimulating an immunogenic response. Some studies suggest that producing reactive oxygen species (ROS) during oxidative stress induces mitochondrial injury. Damaged mitochondrial membrane integrity releases proapoptotic factors like cytochrome c that induce apoptosis and cell death.[15]

Another mechanism of TIN is due to cell injury and insults by bacterial, viral, and fungal infections often associated with preexisting obstruction or reflux. Without obstruction, damage and loss of functions of tubular cells by bacteria are unlikely as the kidney is resistant to structural damage by a bacterial infection. Pathogenesis of other systemic diseases such as sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, SLE, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, Sjögren syndrome, etc., is complex, and it is supposed that multiple factors such as susceptibility to autoimmunity, systemic inflammation, genetic predisposition, nutritional insufficiency, and predisposed infectious agents are involved.[1]

Histopathology

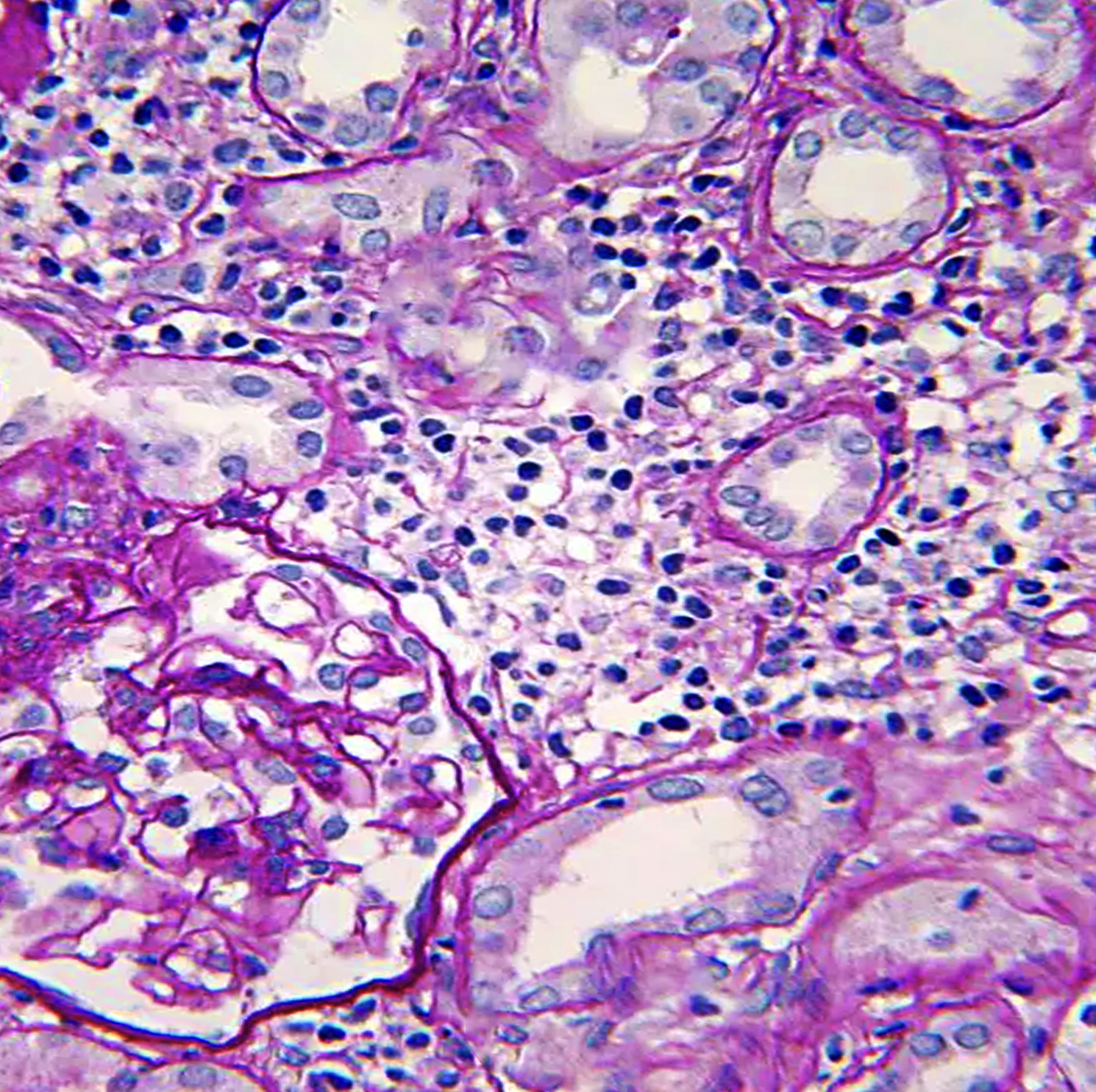

Histopathologic light microscopy in the cases of tubulointerstitial nephritis reveals interstitial inflammatory cell infiltration and edema, regardless of etiology. Inflammatory cells are most commonly lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells, but drug-induced TIN involves eosinophil infiltration. Esopisnophil's presence is not diagnostic of drug-indued TIN as NSAIDs do not involve eosinophils due to their anti-inflammatory nature. The presence of dominant neutrophils and plasma cells suggests a bacterial infection.[18][1] Interstitial inflammation is either focal or diffuse. In addition, there are features of tubulitis, i.e., tubular degenerative changes, irregular luminal contours and ectasia, cytoplasmic simplification, prominent nucleoli, apoptotic figures, loss of brush border, and tubular atrophy due to tubular infiltration of inflammatory cells.[17][19] Granuloma formation with multinucleated giant cells along with foci of necrosis is rare (0.5%), and eventually, this granuloma is replaced by fibrosis.[20]

Immunofluorescence and electron microscopy have fewer features and so are not helpful in diagnosis because it is usually negative in patients with drug-induced TIN, and only rarely methicillin-induced TIN shows immunoglobulins at the tubular basement membrane. The granular or linear deposition pattern in immunofluorescence usually indicates autoimmune diseases and minimal change disease treated with NSAIDs.[17] Glomeruli and renal vasculature become affected in the late disease process and when another superimposed process is also present.

History and Physical

The challenging aspect of tubulointerstitial nephritis is the nonspecific and highly variable clinical presentation that delays the diagnosis and treatment, eventually worsening the outcome. History of onset and duration, age of the patients, and drug intake are of utmost importance while assessing for TIN. The classical presentation of drug-induced hypersensitivity in a study series showed fever (27%), rash (15%), and eosinophilia (23%). The classic triad of fever, rash, and eosinophilia is found in only 10% of cases. Even the symptoms may vary in different classes of medications. However, some studies suggest that allergic features dominate the clinical presentations in drug-induced TIN.[21]

In a retrospective study, acute kidney injury due to medications initially presented without oliguria, but as the disease worsened and progressed, oliguria was seen in 51% and arthralgia in 45%.[5][18] Fever may be absent in drug-induced TIN, including NSAIDs and beta-lactam, but may be present in 50 to 100% of cases of methicillin-induced TIN. Fever is either low grade or intermittently spiking and usually arise within two weeks of treatment but presents early immediately within hours or days in cases of reinfection.[17] About 75% of beta-lactam users may present with hematuria, leukocyturia, and proteinuria. Around two-thirds of patients using rifampicin have associated thrombocytopenia, hepatitis, hemolytic anemia, and proximal tubular cell damage that leads to glycosuria. Myalgia, fatigue, weight loss, anorexia, and headache are common nonspecific symptoms.

On physical examination, skin rashes in the form of morbilliform, maculopapular, erythroderma, and epidermal necrolysis are seen. These rashes are highly variable extrarenal manifestations more common in agents that cause hypersensitive reactions, such as penicillins, sulfonamides, phenytoin, and allopurinol. The kidney is palpable occasionally in severe cases when markedly enlarged. Flank pain and tenderness due to capsular distension by inflammation and edema are likely in those taking rifampicin.[17] Detectable features of nephrotic syndromes, like facial puffiness and pedal edema, are sometimes seen too.[20]

Evaluation

Diagnosis of tubulointerstitial nephritis may be delayed due to nonspecific symptoms. It is challenging to differentiate acute and chronic TIN, and equally important to separate TIN from other causes of renal diseases, such as glomerulonephritis and acute tubular necrosis because treatment and prognosis are different. Clinical assessment, laboratory findings, and imaging tests are the approaches by clinicians to make the diagnosis.

Renal Biopsy

Histopathological view after the renal biopsy is the only definitive diagnosis and gold standard for TIN, which shows characteristic diffuse or focal inflammatory cells (lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, histiocytes) infiltration, edema, and fibrosis along with tubulitis. One should always have a high suspicion of TIN in any patient with renal insufficiency. If there is no clinical improvement even after the withdrawal of offending agents, the patient should be advised for renal biopsy, provided there are no contraindications, and the patient agrees.[22] At times, the composition of inflammatory cells may point out the underlying etiology, such as dominant eosinophils in the drug-induced TIN, with few exceptions like NSAIDs where no eosinophils can be seen, and it should be remembered that drug-induced TIN may contain all other types of inflammatory cells. In addition, a histologic manifestation of tubulitis and tubular cell degeneration supports evidence for the diagnosis of TIN.[19]

Imaging Tests

Renal ultrasonography (USG) and CT scans are often used as imaging studies to support the diagnosis of TIN. These tests reveal bilateral normal to the increased size of the kidney and diffusely increased cortical hyperechogenicity.[17] But these ultrasonography findings cannot exclude or confirm the other causes of renal enlargement, but they help exclude urinary tract obstruction by pinpointing the presence or absence of hydronephrosis.[22] Yet, renal USG and CT scans help exclude other causes of acute kidney injury, such as cysts, masses, or stones. In one report, ultrasonographic evidence of an increase in renal size was reported up to 200% of normal size due to inflammation and edema.[23]

In another study, it was revealed by USG that the increase in the width of the kidney was more significant than in other dimensions.[7] Gallium scintigraphy has been used for over 33 years based upon the binding of gallium to lactoferrin, either expressed on the surfaces of inflammatory cells or produced in the interstitium. So, gallium scanning shows interstitium enhancement compared with the spine. It has a limited role due to low sensitivity and specificity, i.e., 50% to 60%. Lower specificity is due to the positive scan and is also observed in other inflammatory diseases besides TIN, likely glomerulonephritis, atheroemboli, and pyelonephritis. One strong indication of a gallium scan is when a renal biopsy is contraindicated or refused by patients.[19] PET scans can also be used in the diagnosis of biopsy-proven acute TIN. In some cases, even PET scans were found to be positive for gallium scan-negative patients.

Blood Testing

The most significant manifestation of renal failure in TIN is increased blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine. The diagnosis could be considered initially when patients develop a rise in serum creatinine levels.[17] Electrolyte and acid-base disturbances are essentially hyperkalemic, hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis that is out of proportion with the degree of kidney failure, raising clues for associated tubulointerstitial injury.[23][24] Increased eosinophil levels are most commonly linked with drug-induced TIN, principally methicillin beta-lactam (80%), but rare with other non-beta-lactam drugs. Still, sadly, eosinophilia is not sensitive because it may occur in other diseases such as vasculitis, malignancies, eosinophilic leukemia, and cholesterol emboli syndrome. Elevated serum IgE level also implies allergic conditions, basically drug-induced TIN. In addition, decreased erythropoietin synthesis due to tubular cell injury and erythropoietin resistance as a result of undergoing inflammation leads to anemia. Elevated serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive proteins hints at the inflammatory process. Other parameters, such as abnormal liver function tests indicating the associated drug-induced hepatitis, Fanconi syndrome, salt-wasting nephropathy, and urine-concentrating defects, are rarely illustrated.[19]

Urine Analysis and Microscopy

Urine analysis is one of the most commonly used tests and provides a helpful clue to diagnosing TIN. Positive proteinuria in dipstick test and microscopic or macroscopic hematuria is associated with drug-induced TIN in less than 50% of cases but about 90% in beta-lactam antibiotics-induced TIN. Urine leukocytes are present in almost all patients with methicillin-induced TIN but less common with other antibiotics. Esinophiluria (Wright or Hansel stain) is present in the drug-induced acute TIN but not sensitive and specific due to being present in other conditions.[17] Visualization of urine microscopy shows WBC casts in the absence of pyelonephritis. Tubular cell injury by inflammatory process manifests as hyaline and granular casts in around 80% of drug-induced acute TIN. Surprisingly, Rts and WBC casts are seen in only 26% and 14%, respectively. Hence, clinicians should not exclude acute TIN as a cause of AKI based on the presence or absence of pyuria or WBC casts.[1][19] Evaluation of urine chemistry, electrolytes, osmolality, and fractional excretion of sodium do not aid diagnosis.

Diagnosis and monitoring of disease activity are helped by urinary biomarkers, for instance, monocyte chemotactic peptide-1 (MCP-1), alpha1-microglobulin (A1M), and beta2- microglobulin (B2M).[1] These low molecular proteins passed in the urine suggest tubular injury and interstitial pathology. One study with urinary biomarkers concluded that B2M has higher sensitivity and specificity than A1M.[25] MCP-1 is usually observed in the drug-induced TIN.[1]

Treatment / Management

It is essential to have high clinical suspicion to eliminate causative agents of tubulointerstitial nephritis and treat associated systemic disorders. Treatment is supported by the clinician's experience, study series, case reports, and randomized control trials. Therefore, treatment should be according to the underlying etiology. Discontinuation of drugs is the first line of therapy in drug-induced TIN, with alternative drug administration to treat infections that often lead to the reversal of renal injury.[17] However, renal damage may not be completely reversible depending on the duration of exposure of offenders, the degree of tubular atrophy, and the severity of interstitial fibrosis. Corticosteroids have been the mainstay treatment against the inflammatory process, which reduces fibrosis, but randomized control trial poorly supports corticosteroid therapy for long-term renal survival. Limited large retrospective series and controlled trials show inconsistency over the benefits of corticosteroid therapy. Therefore it may be preserved for cases with severe renal failure where dialysis is imminent and renal functions deteriorate despite the removal of offending agents.

A multicenter retrospective study revealed improvement in renal function in cases of early prompt corticosteroid administration after diagnosis and removal of drugs. It showed complete recovery in about 54% of people who received steroid treatment compared to only 33% with no steroid treatment. Also, the need for chronic dialysis is more, i.e., up to 44% in the no corticosteroid treatment group compared to only 4% in the steroid-treated patient group.[26] Another retrospective study comparing non-steroid conservative therapy and steroid therapy did not show significant differences in the outcome based on evaluation and monitoring of serum creatine levels at 1, 6, and 12 months.[5] In contrast, a prospective study of corticosteroid therapy in children having idiopathic TIN and uveitis syndrome produced prompt recovery of TIN, especially in more severe diseases. However, renal function did not vary significantly in control and study groups after six months of follow-up.[27] Whereas patients who did not receive steroids immediately after removal of the culprit have higher baseline creatine levels. The most widely used regimen is methylprednisolone (IV 250-500 mg), followed by prednisone 1 mg/kg/day.[28]

The role of mycophenolate mofetil has been demonstrated in recent studies.[2] It is mainly helpful in steroid-resistant cases and where steroids are contraindicated. Vancomycin-induced granulomatous interstitial nephritis was found to be generally refractory to steroids, and treatment with cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil ameliorated renal function.[29]

Corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants, i.e., azathioprine, is indicated mainly in cases associated with systemic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases such as Sjögren syndrome, sarcoidosis, SLE, TIN with uveitis, and other granulomatous disorders. A retrospective study advocated improved prognosis of corticosteroid use in granulomatous interstitial nephritis regardless of the extent of fibrosis and inflammation on biopsy.[30] Another published case report proposed that corticosteroid treatment in mild tubulointerstitial fibrosis has a better response in the granulomatous TIN. Primarily, corticosteroids have an enormous benefit over sarcoidosis and TIN with uveitis; unfortunately, they have more chances of relapse after withdrawal and need a more prolonged therapy duration than drug-induced TIN.[28] Additionally, cases associated with sarcoidosis can be treated with steroid-sparing agents such as infliximab and azathioprine.[31] IgG4-associated TIN responds well to corticosteroid treatment though the relapse rate after discontinuation is high.[2]

Management of infection-related TIN is the treatment of underlying infections with appropriate antibiotics. Besides, there are no other well-described treatment methods. Corticosteroids have little or no role in an infection-related TIN.[28] In TIN with uveitis, uveitis is treated with topical cycloplegics and corticosteroids, which give around 50% of positive response.[32][33][34] Viral-related transplant rejection is managed by reducing the immunosuppressants and specific retroviral drugs.[35]

Supportive and conservative care should be provided to patients with adverse effects of medications and severe renal failure. These measures include fluid and electrolyte management, avoiding volume depletion or overload, adequate hydration, symptomatic relief of fever, rash and systemic symptoms, avoidance of nephrotoxic drugs, supportive dialysis, etc.[22]

Differential Diagnosis

Clinical presentations and laboratory results of tubulointerstitial nephritis are not specific but rather overlap with most kidney diseases, causing AKI and renal insufficiency. So differentials of TIN include all those causes of AKI. Thus, clinicians use different diagnostic tests, i.e., biopsy, imaging, etc., to differentiate the TIN from AKI because therapeutic interventions differ according to the various causes of AKI. Therefore, while assessing the suspected tubulointerstitial nephritis in patients with renal insufficiency, the following problems should be considered:

Acute Tubular Necrosis

It is the most common cause of acute renal failure characterized by tubular cell necrosis for various reasons, such as ischemia, toxins such as aminoglycosides, heavy metals, urate, radiocontrast dye, ethylene glycol, etc. In addition, clinical manifestations like oliguria, metabolic acidosis, elevated BUN and creatinine, and electrolyte imbalance are similar to TIN.

Atheroembolism

Atheroembolism (cholesterol crystal emboli) should be considered in patients with a predominance of urinary WBC and RBC casts. Atheroemboli may also present with skin rashes, eosinophiluria, and eosinophilia. Skin changes usually include livedo reticularis and digital infarcts rather than the diffuse maculopapular rash of TIN. History of endovascular diseases, old age, and obesity point towards atheroemboli.[36]

Glomerulonephritis

These are a wide range of glomerulopathies, ultimately leading to renal impairment and mimicking TIN. Typical presentations of glomerulonephritis are similar to TIN, such as proteinuria, oliguria, and RBC casts, so visualization of glomeruli and immune complex deposition in light and electron microscopy helps to differentiate different types of glomerulonephritides from TIN.[37]

Vascular Injury

Different cardiovascular insults, likely renal artery stenosis, cardiac failure, vasculitis, reduced blood flow due to afferent arteriolar constriction in NSAIDs users, reduced efferent arteriolar tone by ACE inhibitors, etc., are the common causes of AKI that clinically simulate TIN.

Urinary Tract Obstruction (UTO)

UTO is the postrenal cause of acute renal failure and is usually attributed to renal stones, tumors, and strictures. In patients, anuria or absence of sediment may be due to obstruction as a differential diagnosis. In such patients, imaging helps to distinguish the obstruction from other causes of AKI. Obstruction is the favorable nidus for infection, which drives the ascending infection and, thus, the pyelonephritis sooner or later. Sterile pyuria, WBC casts, leukocytosis, positive dipstick test for leukocyte esterase, and flank pain are the common manifestations.[38]

Prognosis

Prognosis depends upon the cause of tubulointerstitial nephritis, timing of therapy, renal function, previous offending agent, and time of removal of the reason. Chronicity portends worse outcomes. Early identification and removal of the cause improve renal outcomes. In general, drug-induced TIN has a good prognosis because of the potential for partial recovery of the kidney.[17] On the contrary, granulomatous TIN has a poorer prognosis.[28] Prolonged low molecular proteinuria such as A1M, B1M, and MCP-1 is a marker for poor prognosis and decreased glomerular filtration rate.[1]

Long-term prognosis is usually encouraging with full kidney recovery.[18] Adverse prognostic factors include diffuse inflammation versus better outcomes in patchy inflammation. The abundance of inflammatory cells and extensive fibrosis means a bad prognosis. Patients who halt the offending medication within two weeks of the commencement are more inclined to recover nearly baseline function than those taking medication for three or more weeks.[22]

Complications

Older patients are more vulnerable to complications. A delay in diagnosis and treatment worsens the condition. Renal insufficiency is a common manifestation that ultimately progresses to end-stage renal disease. The inflammatory interstitium is entirely replaced by fibrosis, and severe degeneration of tubular epithelial cells induces irreversible renal impairment necessitating early renal replacement therapy. Initially, glomeruli are usually spared, but later on, glomeruli are also involved. Damage of glomeruli provokes the hyperfiltration of proteins, glucose, blood cells, and other essential components of blood. The insufficiency of reabsorption from damaged renal tubular cells causes an excessive renal loss of body electrolytes. Also, there is an acid-base imbalance causing hypokalemic metabolic acidosis.

The involvement of proximal tubules, especially in TIN with uveitis, heightens the chances of glycosuria, hyperphosphatemia, hyperuricosuria, proximal renal tubular acidosis, aminoaciduria, proximal renal tubular acidosis, and kaliuresis, which is described as Fanconi syndrome.[39][40][41] In one case report, a 39-year-old man was reported with bone pains, polydipsia, and polyuria due to loss of phosphate in the urine, leading to hypophosphatemic osteomalacia and osteoporosis in Sjögren syndrome-associated TIN. It concluded that bone disorders are among the rare complications.[42]

Some cases of TIN result from antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)-associated vasculitis and transform to necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis when corticosteroid therapy is delayed.[43] The involvement of proximal renal tubular cells due to inflammation or infection results in either decreased synthesis or hyporesponsiveness of erythropoietin by injured cells leading to reduced stimulation of bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells for RBC production, ultimately causing anemia.[19] Frequent use of NSAIDs may trigger the development and progression of nephrotic syndrome. Nephrotic and nephritic syndrome in long-standing cases of the TIN present with pitting edema due to hypoalbuminemia. There is an increased risk of infection due to hypogammaglobulinemia, hyperlipidemia, periorbital edema, hematuria, and azotemia.

Tubulointerstitial inflammation increases angiotensin II activity, which leads to arterial hypertension due to sodium retention and increases oxidative stress.[13][44] Increased angiotensin concentration changes the hemodynamic status and oxidative stress, causing vasoconstriction.[45][46] Lupus nephritis-related persistent arterial hypertension is also conspicuous in about two-thirds of cases.[44]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Information provided to patients about the disease and course of treatment should be understandable. Well-educated patients who want in-depth knowledge are provided with more sophisticated and detailed notes about the procedure. Every patient has the right to know about their disease. This helps to decrease the communication gap between clinicians and patients. Patient education also assists the patients in clearing their doubts and motivates them to tackle their problems. In this way, patients become optimistic and compliant with routine therapy and cooperate with clinicians. So, health education has always been a high priority. Briefing about the disease, signs and symptoms, treatment options, side effects, and complications enables the patients to make appropriate decisions and present early in the clinic. Preventive measures, diagnostic tests, and consent before invasive interventions come under patient education.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

In most countries, an enhanced healthcare system is still unavailable. The interprofessional healthcare approach has always been highly appreciated and desired, which brings about a better outcome. Resource-rich countries are already working through multiple healthcare teams to make precise diagnoses and imply appropriate treatment. The need for different professionals depends upon the complexity of the disease process. Tubulointerstitial nephritis has a wide range of etiology, which needs clinicians from various specializations, such as nephrologists, urologists, infectious disease experts, ophthalmologists in cases of TIN with uveitis, and pulmonologists.[32] These disciplines coordinating their efforts, maintaining meticulous patient records, and executing open communication lines will bring about the best possible patient outcomes.

Diagnostic approaches can be made effective with the help of histopathologists, radiologists, lab technicians, and microbiologists. Skin rashes in drug-induced hypersensitivity can be managed with the help of dermatologists. Nursing care of patients is an inseparable entity in every hospitalized patient, and pharmacists provide drug education and review side effects. Surgeons have their role in biopsy and chronic kidney disease in renal transplantation with the aid of anesthetists. This way, the comprehensive interprofessional healthcare team drives better results with fewer adverse outcomes.